The Strange Tale of the Fighting Model T Fords

While writing my next novel in the Western Desert of Egypt (something I’ve discussed in several previous posts), I came across an interesting local landmark. Behind my campsite in Bahariya Oasis stands a grim heap of black volcanic stone called “English Mountain”. When I asked around about this unusual name, the local Bedouin told me that it was once home to an English soldier who kept watch for attacking tribes back in the days when Egypt was still a colony. I was told the ruins of his house could still be seen.

So of course I went up to see them!

But not before taking Ahmed Fakhry’s excellent book Bahariya and Farafra out of my backpack to see what he had to say about this. Yes, I travel through the Sahara with a bag full of books.

Written in 1974 but mostly based on expeditions the archaeologist took in the 1930s, Fakhry’s book is full of useful information and folklore. In it he says that English Mountain is actually named after a New Zealander named Claud Williams, who commanded No. 5 Light Car Patrol during World War One. Williams, Fakhry says, kept a lonely vigil atop that mountain for hostile Senussi tribesmen.

And therein lies a tale.

Rolls Royce armored car in Palestine. Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

The Senussi are a religious order that originated in Libya in the late 18th century. They were a reformist movement among the Sufi orders but never became as strict as the Wahabi sect coming in from Saudi Arabia. One of the distinctive features about the Senussi was that they were deeply anti-foreign. In the early days, a Senussi wasn’t even supposed to speak to a non-Muslim. When the Italians took Libya from the Ottomans in 1912, the Senussi rose up against them.

When World War One started, the Ottomans and the Germans encouraged the Senussi to invade British Egypt and supplied them with weapons. The Senussi got even more when they handed the Italians a decisive defeat and took as booty thousands of rifles and a good supply of machine guns and artillery. Pushing east across the border, they took many of the border and coastal towns in Egypt as well as many of the oases in the Western Desert, including Bahariya.

Unidentified Australian Light Car Patrol in Palestine.

Image courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Something needed to be done. Egypt was the vital link between the Mediterranean and the jewel in the British Empire’s crown — India. Egypt also contributed a huge amount of manpower, grain, and cotton to the war effort. British officials feared an uprising, and so they needed to secure the desert as quickly as possible.

Enter the Western Frontier Force, a hastily assembled group of men from all parts of the empire that included two of the war’s many innovations. The first was the Light Car Patrol, made up of Model T Fords that had been stripped of all excess weight (even the hood and doors) so they could run over soft sand. Many came equipped with a machine gun. Heavier and slower were the armored cars, built on the large Rolls Royce chassis and sporting a turret and machine gun.

The Senussi had nothing that could stand against such superior firepower and maneuverability except their captured artillery, which was generally too slow in traversing and aiming to be much good.

The campaign ended within a year, with the Western Frontier Force snapping up victory after victory. At times, the motor vehicles ranged far and wide, saving captured Allied troops, cutting off retreats, and blowing through Senussi camps without warning. Soon the Libyans were sent packing and many of the Model Ts and armored cars went to join the fighting in Palestine.

But after the Senussi were expelled from Egypt, the job of the Light Car Patrols was not yet finished. The British feared the Senussi’s return, and also needed to stop illicit trading across the desert. The Light Car Patrols, including Claud Williams’ unit, spent many long months in remote patches of desert tracking down Bedouin smugglers and mapping large swathes of unknown territory. The patrols laid the groundwork for further exploration of the Western Desert as well as for desert car travel.

It wasn’t all easy going. Some men got killed by Bedouin smugglers, while others broke down in the middle of nowhere and died terrible deaths of thirst. While the Western Desert wasn’t the meat grinder of the Western Front, it wasn’t a cushy posting either.

The ruined house on English Mountain

Armed with this knowledge, I climbed English Mountain to the ruins of the house. I was surprised at how big it was, with several rooms and portions of wall still standing higher than my head. All sorts of scenes and images came to my head of Williams, who had now become part of the supporting cast of my novel, keeping watch for raiders and smugglers and calling back status reports on the wireless to the station in Cairo.

He was too good of a character not to use. One of the things I love about historical fiction is how I get to mix real events and people with my made-up amateur sleuths. Williams had the local knowledge and flashy car my characters needed to solve the mystery, not to mention a fair bit of firepower for the several tight spots they were going to get in.

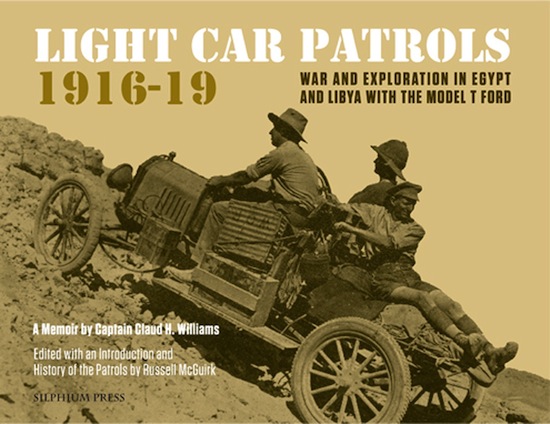

So when I returned home with the book half finished, I immediately ordered Light Car Patrols 1916-19: War and Exploration in Egypt and Libya with the Model T Ford, edited by Russell McGuirk and containing both the historical background of the campaign and a manuscript written by Williams himself.

English Mountain, with the ruins in the distance

It’s a beautifully produced book, with pullout maps, lavishly illustrated with period photos, and informative text. Anyone interested in desert exploration or World War One’s lesser-known campaigns should pick up a copy.

Turned out that text was a little too informative. McGuirk researched the tale of English Mountain and found that the local folklore was wrong. Williams was never posted on the mountain, and in fact had left the Western Desert by spring of 1919 when my heroes arrive. McGuirk wasn’t able to find out who actually did build the structure, although he mentions another bit of folklore saying that it was built by a British officer during World War Two, when the Western Desert once again became a battleground and the lessons learned by the Light Car Patrols were used by a different generation of fighting men. So it may have been a military outpost, but not one used by Captain Williams.

What to do? The book is already more than halfway done.

Hell with it! This is fiction, after all, and the story of the Light Car Patrols is too interesting to leave out. I always have a historical note at the end of my novels where I explain a bit of the background and admit to where I played with history. It’s just going to be a bit longer in this one.

I think I’ll be forgiven for giving Captain Williams one last adventure in the Western Desert.

English Mountain offers a good viewpoint of all the approaches to Bahariya Oasis

Photos copyright Sean McLachlan unless otherwise noted.

Sean McLachlan is the author of the historical fantasy novel A Fine Likeness, set in Civil War Missouri, and several other titles. Find out more about him on his blog and Amazon author’s page. His latest book, The Case of the Purloined Pyramid, is a neo-pulp detective novel set in Cairo in 1919.

Sean,

What a great tale! Thanks for sharing it.

[…] (Black Gate): Enter the Western Frontier Force, a hastily assembled group of men from all parts of the empire […]