Fantasia 2018, Special Screenings: Buffalo Boys, Luz, and Crisis Jung

Before writing about the movies I saw during the last weekdays of the Fantasia festival, I’m going to skip back to the beginning to write about some films I watched before attending my first screening this year with a general audience. At a festival with 130 movies, most of which are shown in a theatre once or maybe twice, one has to make some hard choices about which to see. Fortunately, Fantasia’s screening room gives harried film critics the chance to catch some of the movies they have to miss in theatres due to one scheduling exigency or another. I passed by on the first day of the festival, and found that this year the screening room offered curtained cubicles and a healthy selection of films. Among them was an Indonesian western named Buffalo Boys, an experimental German horror film called Luz, and a transgressive French animated webseries titled Crisis Jung.

Before writing about the movies I saw during the last weekdays of the Fantasia festival, I’m going to skip back to the beginning to write about some films I watched before attending my first screening this year with a general audience. At a festival with 130 movies, most of which are shown in a theatre once or maybe twice, one has to make some hard choices about which to see. Fortunately, Fantasia’s screening room gives harried film critics the chance to catch some of the movies they have to miss in theatres due to one scheduling exigency or another. I passed by on the first day of the festival, and found that this year the screening room offered curtained cubicles and a healthy selection of films. Among them was an Indonesian western named Buffalo Boys, an experimental German horror film called Luz, and a transgressive French animated webseries titled Crisis Jung.

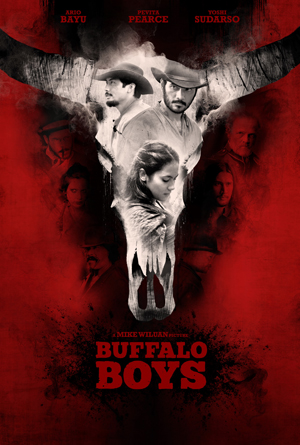

The festival hosted the world premiere of Mike Wiluan’s Buffalo Boys, but, knowing I’d miss its theatrical showing, it became the first film I saw in the screening room. Directed by Wiluan from a script by Raymond Lee, Rayya Makarim, and Wiluan, it’s an Indonesian take on the Western genre. In the 19th century, the Dutch attempt to consolidate control of Indonesia; a Dutch agent murders a rebellious sultan, but the sultan’s brother and infant sons escape. Decades later, as they travel the American west, the sultan’s brother, Arana (Tio Pakusadewo), decides it’s time for them to return to Java so that his brother’s sons can seek justice for their father. The elder son, Jamar (Ario Bayu), has grown into a strong man, skilled in hand-to-hand fighting; his brother, Suwo (Yoshi Sudarso), is less confrontational but more charismatic — and good with a knife. The three of them make their way to the territory now ruled by the tyrannical Dutchman Van Trach (Reinout Bussemaker), where they stop an attempted robbery and become involved with the daughters of a local chief, all of whom are threatened by Van Trach’s machinations.

The movie opens by noting that “this is one story where fact and fiction collide,” and ends with a character observing that “when legends are born they never die.” This is a film conscious not only of its genre, but of the mythic underpinnings that give the genre strength. The paraphernalia of the western film’s used well: twanging guitars on the soundtrack, lens flares, gunfights, conversations around a campfire at night. But it’s fused with the martial-arts action movie: fights are a whirl of punches, kicks, knife strikes — and then, where logical and necessary, gunplay. One scene in the middle of the film, in a saloon, brings home the way the movie at its best fuses different cinematic traditions of action and stylised violence.

But the movie’s about more than action, and in fact the number of fight scenes is relatively restrained. It’s even possible to argue that the violence at the climax is too short, the build to the final tense standoff too quick. That’s because the movie’s interested in its setting: in the injustices done by the Dutch, but also in its extended cast of characters. The leads recede somewhat during the middle section of the film, as the wrongs done by the authorities multiply, calling out for revenge.

But the movie’s about more than action, and in fact the number of fight scenes is relatively restrained. It’s even possible to argue that the violence at the climax is too short, the build to the final tense standoff too quick. That’s because the movie’s interested in its setting: in the injustices done by the Dutch, but also in its extended cast of characters. The leads recede somewhat during the middle section of the film, as the wrongs done by the authorities multiply, calling out for revenge.

It’s worth noting that this is a film in which sexual violence is a recurring theme, either threatened or depicted. There’s also a willingness to show blood and empty eye sockets, so this is a movie that lives for extended stretches in the lurid and exploitative. It’s an odd choice, in that at other points the tone’s much lighter. As if the horrors of colonial exploitation overwhelm the relatively high-spirited action film that it sets out to be, dragging it to a darker tone. But then the movie’s also possessed of a certain kind of genre energy that interacts with the theme of colonialism — it’s about exploitation in two completely different senses.

Worth noting here that I’m a North American with no family or cultural connection to Indonesia; I’m reviewing this movie as a movie that played in a North American city (and which for all I know might become accessible to viewers in North America and around the world through the miracles of Netflix or video-on-demand). This is a film that deals with Indonesian history and (as I understand it) consciously uses the Western genre trappings as a way to approach the colonial history of Indonesia: one character rejects a gift from Van Trach, telling him “I do not want to be linked to your past,” and then suffers for it. This perhaps sounds dull. But this is not a dull movie. It’s fast and entertaining and pleasurably violent. My point is that even I can see that it’s also engaged with history in a way that gives it an unusual heft.

In a lot of American Westerns I’ve seen, a lone gunman or small group of heroes turn up in a community overrun by villainy, shoot some bad guys, and set matters right. In other cases the bad guys may be trying to invade a peaceful community, but the basic idea’s the same: at the end of the story violence has restored some kind of order. That’s not really possible in this case, as the heroes are specifically fighting against an evil authority. Realistically, a few individuals haven’t a hope against an intercontinental system. But then this returns us to the film’s speculation about legends. It’s a film that knows what it’s up against, in other words, and handles its themes deftly.

In a lot of American Westerns I’ve seen, a lone gunman or small group of heroes turn up in a community overrun by villainy, shoot some bad guys, and set matters right. In other cases the bad guys may be trying to invade a peaceful community, but the basic idea’s the same: at the end of the story violence has restored some kind of order. That’s not really possible in this case, as the heroes are specifically fighting against an evil authority. Realistically, a few individuals haven’t a hope against an intercontinental system. But then this returns us to the film’s speculation about legends. It’s a film that knows what it’s up against, in other words, and handles its themes deftly.

(It’s interesting to consider some of the details here. The title’s explained in the course of the film, a reference to the buffalos of Indonesia, but it’s hard not to hear an echo of Buffalo Soldiers, the name given by Indigenous Americans to African-American soldiers. It’s also interesting to note that when the brothers spot an archer riding a buffalo, one immediately compares her to the Apache. That’s a nice character moment, the brothers interpreting their homeland in terms of the land where they grew up, but it also seems to hint at the movie’s awareness of a colonial subtext to the Western form, and its attempt to reimagine the Western in an anticolonialist way.)

If the Western is a foreign form to Indonesia, it’s assimilated well here. The brothers make interesting lead characters: they’re bilingual, and indeed, having been away from the land of their birth since infancy, have to consciously relearn Indonesian traditions. Bayu and Sudarso seem to have good chemistry as brothers; one wishes they’d been given a few more scenes to explore their relationship and interact with each other. Certainly they both establish their characters as solid Western archetypes, Bayu playing Jamar as the violent masculine force of nature, Sudarso’s Suwo the fast-talking face. Worth noting that Suwo gets an interesting scene with a woman-warrior named Kiona (Pevita Pearce) in which the characters compare the way they’re both imprisoned by gender roles; it lends valuable depth to both of them, while establishing useful subtext for the film as a whole.

Visually, this film’s a pleasure to watch. The cinematography’s excellent, the bright sunlight of the California-set opening giving way to the more textured and varied light of Indonesia. Costumes and props are designed with attention, creating a memorable array of only slightly cartoony mini-bosses, but also adding details — some buttons here, a necklace there — helping to show the depth and background of a character like Arana. There’s a sense of high production values, even of lushness; unobtrusively, the movie builds a world, and implies that there’s more to the world than just what we happen to see onscreen. The fights are edited with a tight narrative discipline: shots never go on longer than they need to just for the sake of showing off a cool move. Everything’s cut to tell the story, to make clear what’s going on where. The heart of the movie isn’t in the fights, not exactly, though they are structurally crucial in a way that makes sense. The point is the story, and Buffalo Boys, aware of the way that stories become legend, delivers its story quite nicely.

Visually, this film’s a pleasure to watch. The cinematography’s excellent, the bright sunlight of the California-set opening giving way to the more textured and varied light of Indonesia. Costumes and props are designed with attention, creating a memorable array of only slightly cartoony mini-bosses, but also adding details — some buttons here, a necklace there — helping to show the depth and background of a character like Arana. There’s a sense of high production values, even of lushness; unobtrusively, the movie builds a world, and implies that there’s more to the world than just what we happen to see onscreen. The fights are edited with a tight narrative discipline: shots never go on longer than they need to just for the sake of showing off a cool move. Everything’s cut to tell the story, to make clear what’s going on where. The heart of the movie isn’t in the fights, not exactly, though they are structurally crucial in a way that makes sense. The point is the story, and Buffalo Boys, aware of the way that stories become legend, delivers its story quite nicely.

Thanks to the estimable Dave Harris, I can pass along a few moments from the question-and-answer period that followed the film’s screening at Fantasia. The filmmakers spoke about making a “fried rice western,” and mentioned an online comic tie-in. They noted that they’d hoped to have more of a role for the women. They had the Dutch characters speak English so that they could avoid having two sets of subtitles onscreen. And they ensured that the weapons used were period-accurate.

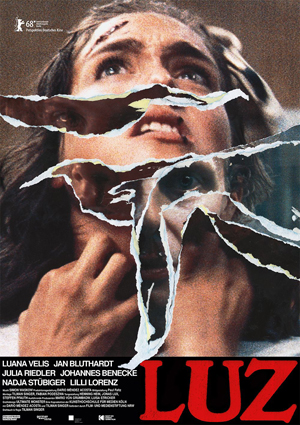

Late the next day I would watch Five Fingers of Death; before that, in the afternoon, I headed down to the De Sève Theatre for a press screening of a German film called Luz. I’d seen the programmers recommend it in some pre-festival interviews, and the description in the Fantasia program guide intrigued me. Both times it played it was against another film I wanted to see, so I was happy to take advantage of a theatrical screening for the press. Sometimes things just work out. (In fact, interest in the film would grow through the festival, and multiple later press screenings would be scheduled; it’s an example of a movie that generated that elusive thing called “buzz.”)

Late the next day I would watch Five Fingers of Death; before that, in the afternoon, I headed down to the De Sève Theatre for a press screening of a German film called Luz. I’d seen the programmers recommend it in some pre-festival interviews, and the description in the Fantasia program guide intrigued me. Both times it played it was against another film I wanted to see, so I was happy to take advantage of a theatrical screening for the press. Sometimes things just work out. (In fact, interest in the film would grow through the festival, and multiple later press screenings would be scheduled; it’s an example of a movie that generated that elusive thing called “buzz.”)

The feature film debut for writer-director Tilman Singer, Luz begins with a long take of a police station somewhere in Germany. A young woman with a head wound (Luana Velis) enters and asks the desk sergeant if this is how he wants to live his life. The woman turns out to be a Spanish-speaking cab driver named Luz; two plainclothes officers (Nadja Stübiger and Johannes Benecke) try to communicate with her, but need to call in the help of a psychiatrist named Rossini (Jan Bluthardt). Who at that moment is in a bar, in a strange conversation with a woman named Nora (Julia Riedler), who herself is linked to Luz’s past and to a strange incident at a Catholic girl’s school involving a spiritual possession. By the time Rossini arrives at the station we’ve seen him changed by his encounter with Nora, and we know the supernatural is already at work.

Most of the film takes place in the police station as Rossini hypnotises Luz and draws out her memories. Figures from Luz’s past, recent and distant, appear and disappear. The two police officers are caught up in the strange game Rossini plays. The movie becomes a huis clos, a limited cast imprisoned in a single location, but Singer plays with this theatrical convention to make the single set a stage in which Luz’s past comes to life.

Singer uses a (presumably) low budget to strong effect, fog and light and especially sound to creating a world of shifting memories. The story, enclosed in one location, runs the very real risk of feeling stagy. But if it is tempting to imagine how entrances and exits could be managed theatrically, ultimately Luz succeeds cinematically, feeling like a story that could only be told on film if only because of its manipulation of the camera’s (and so audience’s) point of view.

This is an experimental horror film. Only 70 minutes long, it’s also a slow burn, beginning with a long take with the camera locked in place, and proceeding through an editing rhythm that shuns jump scares for lingering shots. That rhythm, Singer’s framing of his shots, makes it work: he controls what we see and when, in a way native to the horror movie. It’s shot in 16mm, and the visual crackle of the film adds an odd texture to the story, as does the echoing sound. Late in the movie a strange mist fills the room where Rossini’s hypnotised Luz, and the dance of the film grain gives a weird energy to the proceedings: the matter of the film itself, the light we’re seeing on the screen, is animated, is crawling over itself. Judging from Luz’s name, ‘light’ in Spanish, one would think light would be an important symbol in the film — and indeed it is, though I found it difficult to associate any specific meaning to it. Perhaps it’s simply what remains when all else is stripped away.

This is an experimental horror film. Only 70 minutes long, it’s also a slow burn, beginning with a long take with the camera locked in place, and proceeding through an editing rhythm that shuns jump scares for lingering shots. That rhythm, Singer’s framing of his shots, makes it work: he controls what we see and when, in a way native to the horror movie. It’s shot in 16mm, and the visual crackle of the film adds an odd texture to the story, as does the echoing sound. Late in the movie a strange mist fills the room where Rossini’s hypnotised Luz, and the dance of the film grain gives a weird energy to the proceedings: the matter of the film itself, the light we’re seeing on the screen, is animated, is crawling over itself. Judging from Luz’s name, ‘light’ in Spanish, one would think light would be an important symbol in the film — and indeed it is, though I found it difficult to associate any specific meaning to it. Perhaps it’s simply what remains when all else is stripped away.

Luz is an involving film, but at first viewing I’d say not one with a particularly tight plot. We understand what Rossini wants from Luz when he arrives at the station, but not the way he chooses to go about it; why he goes through the process he does. Still, we know enough of what’s going on to be drawn into the action if we’re at all sympathetic to the film’s ambitions: moments that might be funny become uncanny because we know what they mean. The movie’s an experience, one that sticks in the mind.

I will say it never really becomes terrifying. There’s no sense for me that there’s much at stake. So much of the film has to do with memories that it seems all the crucial choices in the story were made before the film began. Usually a film about spirits and demons and religious ritual has to do with salvation and damnation, but in this case I couldn’t see that a choice for either was taken during the course of the story. It’s difficult even to see the movie as a working-out of a tragedy; it’s a set of events that begins with the characters in one place, ends with them in another, and (again, at one viewing) leaves me unsure what I’m meant to take away as the difference. Luz is an interesting character, played well by Velis, but to me feels more of an archetype than an individual. While the end of her story is touching, it’s not horrifying.

I will say it never really becomes terrifying. There’s no sense for me that there’s much at stake. So much of the film has to do with memories that it seems all the crucial choices in the story were made before the film began. Usually a film about spirits and demons and religious ritual has to do with salvation and damnation, but in this case I couldn’t see that a choice for either was taken during the course of the story. It’s difficult even to see the movie as a working-out of a tragedy; it’s a set of events that begins with the characters in one place, ends with them in another, and (again, at one viewing) leaves me unsure what I’m meant to take away as the difference. Luz is an interesting character, played well by Velis, but to me feels more of an archetype than an individual. While the end of her story is touching, it’s not horrifying.

Worth noting that this is a period piece, set at some point when pagers and CRT TVs were the norm. In other words, no smartphones and no internet. Singer makes good use of the setting, though, echoing it with the technology of his camera and indeed his stylistic approach — I’ve seen Fassbinder, Zulawski, and Fulci invoked to describe the feel of his film. The setting isn’t just a plot convenience, in other words, but helps determine the style of the visuals and the soundtrack: synth-heavy electronics dominate.

This is a film that’s conscious of itself as a film. Early on, we’re told the rituals around the supernatural “depends on what movies people have seen.” There’s a consciousness of artifice here, in other words, but there’s also a fluidity of technique that draws the viewer in despite the artifice, despite even the looseness of the plot. The overall arc of the characters are clear, and that’s enough. The actors aren’t artificial, and build to big moments logically. Bluthardt’s Rossini may be especially worth noting, as a role that goes strange places always comes off as coherent.

This is a film that’s conscious of itself as a film. Early on, we’re told the rituals around the supernatural “depends on what movies people have seen.” There’s a consciousness of artifice here, in other words, but there’s also a fluidity of technique that draws the viewer in despite the artifice, despite even the looseness of the plot. The overall arc of the characters are clear, and that’s enough. The actors aren’t artificial, and build to big moments logically. Bluthardt’s Rossini may be especially worth noting, as a role that goes strange places always comes off as coherent.

Luz is not a film that is filled with easy narrative pleasures. But it’s solid enough as filmmaking to be engaging if not (I can’t avoid the word) hypnotic. As horror, it’s not especially frightening. As a movie, though, it’s rewarding.

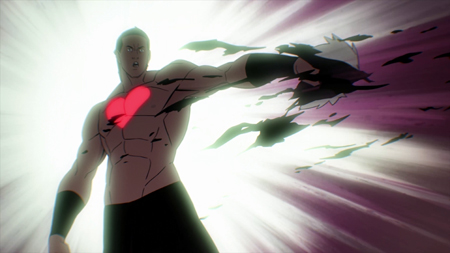

After Luz ended I decided to try my luck in the festival screening room, and wandered over to watch a film called Crisis Jung. This was a movie I had misgivings about, and those misgivings were realised in spades. I will note up front that I am not the target audience for Jung, and that it apparently did later play to an enthusiastic crowd in the theatre. Still, even beyond what it was doing I thought there were issues with how it went about what it was trying to do. Directed by Baptiste Gaubert and Jérémie Hoarau, written by Gaubert with Jérémie Périn, Crisis Jung is a web serial that’s available through the Blackpills app, a French digital-media firm that presents free ad-supported series aimed at younger viewers. The creators of Crisis Jung are with Bobbypills, an animation studio that describes itself as “an animation studio in Paris full of depressive, beautiful, fucked up people making cartoons for depressive, beautiful, fucked up people.”

The story begins with Jung and Maria, a young couple in love in a beautiful utopian landscape. Enter the gigantic Little Jesus, who devastates the land with violence and decapitates Maria in front of Jung before flicking Jung away across the landscape. Nothing daunted, Jung returns as a superhero with a fighting technique based around 10 big punches, seeking to be reunited with his one true love, who still lives even though headless. He has to face Little Jesus’s goons, naked men with full-size chainsaws for genitals, and fight monsters that Little Jesus literally shits out. His allies include Thunder Dominic, a cannibalistic giant who has Maria’s headless naked body strapped to his chest, and Marie-Madeleine, a bearded woman with a man’s body who wears a topless slave-girl outfit. (In fact all the women in this world are men who, apparently, are led by circumstances to assume a woman’s identity.)

The story begins with Jung and Maria, a young couple in love in a beautiful utopian landscape. Enter the gigantic Little Jesus, who devastates the land with violence and decapitates Maria in front of Jung before flicking Jung away across the landscape. Nothing daunted, Jung returns as a superhero with a fighting technique based around 10 big punches, seeking to be reunited with his one true love, who still lives even though headless. He has to face Little Jesus’s goons, naked men with full-size chainsaws for genitals, and fight monsters that Little Jesus literally shits out. His allies include Thunder Dominic, a cannibalistic giant who has Maria’s headless naked body strapped to his chest, and Marie-Madeleine, a bearded woman with a man’s body who wears a topless slave-girl outfit. (In fact all the women in this world are men who, apparently, are led by circumstances to assume a woman’s identity.)

Each chapter, most named for a quality or virtue, follows the same basic formula: Jung and his gang come to an obstacle, cross it, and Little Jesus excretes a monster for them to fight. Jung attacks it with his punching technique, is thrown away, weeps as he’s thrown through the air, and when the tear lands on the ground a stone hand bursts out of the soil to catch Jung and lead him to a kind of internal monologue with a psychiatrist who provides a homily on whatever the title of the episode is. Jung’s reborn in a muscular female body, and destroys the monster with the new body’s powers — clawlike fingernails, laser beams from the nipples, breast milk that Jung gargles and spits out as shrieking plasma.

This may sound reasonably inventive, but over 70 minutes it wears thin. The transgressive quality of the story’s lost to repetition. After about chapter five, there’s no new grotesquerie to surprise the viewer. Personally, I felt that the grotesque was not enough even when new things were being presented; but I don’t see how someone looking for the outrageous will find enough in the back half of the serial to keep them going. (Unless, as I say, they’re watching in a theatre full of like-minded souls.)

This may sound reasonably inventive, but over 70 minutes it wears thin. The transgressive quality of the story’s lost to repetition. After about chapter five, there’s no new grotesquerie to surprise the viewer. Personally, I felt that the grotesque was not enough even when new things were being presented; but I don’t see how someone looking for the outrageous will find enough in the back half of the serial to keep them going. (Unless, as I say, they’re watching in a theatre full of like-minded souls.)

There isn’t really any humour beyond a straight-faced parody of a Hollywood hero’s journey. Occasionally Jung comes across something like the Abyss That Cannot by Bypassed, which is vaguely amusing, but, again, insufficient. I had hoped (based on the trailer and a few still images I saw) that even if it was primarily parodic that there’d still be a good amount of Métal Hurlant–ish imagery. There are a few moments like that, but deducting them from the 70-minute run time still leaves maybe 68 minutes of bare-bones animation. I will say that it’s not painful to watch, in that the animation’s effective, reasonably smooth, and comptently parodies over-the-top anime fight scenes. Up to a point the designs are solid. But, as with so much else, after a few episodes they become repetitive.

I can, stretching things considerably, see how Jung’s various incarnations reflect the archetypes Carl Jung popularised: the psychiatrist his shadow, the female version of himself his anima. So externally Little Jesus is his shadow and Maria his anima; and the story is about Jung uniting the archetypes internally before being able to do the same in the outside world. It’s possible to make that argument, I suppose. But it doesn’t really help the story. Subtext or no subtext, Crisis Jung is shallow, and a brief visual reference to a Goya painting did not strike me as having much relevance.

What I think is most baffling about the show is the repetitiveness of its structure, the same story episode after episode. The fifth episode deliberately breaks the pattern, having Jung go through his crisis in the background as we follow a castrated former chainsaw wielder. In other words: the creators know they’ve set up a repetitive pattern, and return to it anyway. I can only guess that this is a parody of anime, possibly older shows like Goldorak (AKA Grandizer, originally Gurendaizâ or UFOロボ グレンダイザ, a 1975 anime series that, translated into French, became a hit across the Francophone world). The thing is, I strongly suspect I`d have more fun watching some formulaic Golodorak episodes than the shorter but frankly less inspired Crisis Jung.

What I think is most baffling about the show is the repetitiveness of its structure, the same story episode after episode. The fifth episode deliberately breaks the pattern, having Jung go through his crisis in the background as we follow a castrated former chainsaw wielder. In other words: the creators know they’ve set up a repetitive pattern, and return to it anyway. I can only guess that this is a parody of anime, possibly older shows like Goldorak (AKA Grandizer, originally Gurendaizâ or UFOロボ グレンダイザ, a 1975 anime series that, translated into French, became a hit across the Francophone world). The thing is, I strongly suspect I`d have more fun watching some formulaic Golodorak episodes than the shorter but frankly less inspired Crisis Jung.

As I say, though, this is not a movie for me. It’s not surprising that I didn’t enjoy it. I’m just not sure who would enjoy it outside of a certain kind of midnight-movie setting. I don’t think there’s enough here to keep an audience engaged for well over an hour at one go. It might work better broken into two halves; it might not. There is something here that can be read as subtext, but the humour strikes me as typically too obvious and minimal to work — and it does require an ability to laugh at things like cannibalism and young children having their arms cut off. If that doesn’t sound like something of interest, this is certainly a work to avoid; if it does, I still wouldn’t recommend it.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I wish I had fallen in love with “Buffalo Boys” the same way that you and David did — I love new (and foreign) takes on “the Western” far more than most typical Westerns. But it was too sloppy for me, tying together far too well, with far too little time spent on the villain (the movie’s only interesting character as far as I was concerned) and far too much reveling in strangely Disney-fied action fluorishes and silly humour (the scenes involving the hand-kissing introduction and the nude bathing by the washer-women felt Extremely forced, as did the “gearing up” montage before the out-of-the-blue show down).

If it had gone full tilt playful or full tilt menacing, I would probably have been much more entertained — as it stands, it jumps too much between the contrasting tones of “the Three Amigos” and “the Proposition”.

With “Luz” we’ll have to agree to differ. My views can be found by those in the know.

And “Crisis Jung” — you are spot on with your review. I just somehow managed to really enjoy it. The one thing I will remark in its favour, though, in regards to the repetitiveness: that’s a hallmark of epic adventure yarns throughout the ages; that coupled with the fact that this was a web series designed with a (very) specific audience in mind, the only aspect of the repetitiveness I minded was the inclusion of the opening and closing credits Each Time.

I can certainly understand the tonal shifts of Buffalo Boys being difficult to swallow. I found myself going with it, but it definitely stood out.

(Those not yet in the know, incidentally, might want to check out 366weirdmovies.com, and potentially become wise!)

I’m legitimately glad you enjoyed Crisis Jung!