Fantasia 2017, Day 20: Human and Inhuman (Lu Over the Wall, Spoor, and Nomad)

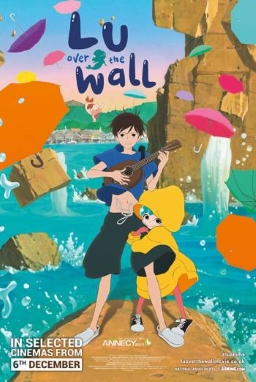

Tuesday, August 1, was the next-to-last day of Fantasia. I had three films I wanted to see as the festival raced to its end, all at the De Sève Theatre. Lu Over the Wall (Yoake Tsugeru Lu no uta) was an animated young person’s adventure about indie rock and mermaids, from the mind of Masaaki Yuasa. Spoor (Pokot) was a Polish-Czech co-production of a mystery-horror film about animals that may or may not be turning against human beings. And Nomad (Göçebe) was a Turkish science-fiction/fantasy film that promised mythic overtones.

Tuesday, August 1, was the next-to-last day of Fantasia. I had three films I wanted to see as the festival raced to its end, all at the De Sève Theatre. Lu Over the Wall (Yoake Tsugeru Lu no uta) was an animated young person’s adventure about indie rock and mermaids, from the mind of Masaaki Yuasa. Spoor (Pokot) was a Polish-Czech co-production of a mystery-horror film about animals that may or may not be turning against human beings. And Nomad (Göçebe) was a Turkish science-fiction/fantasy film that promised mythic overtones.

Lu Over the Wall was the second movie directed by Masaaki Yuasa I saw at Fantasia this year, having watched Night Is Short, Walk On Girl just the day before. This one, written by Yuasa and Reiko Yoshida, is an original story about Kai (Shota Shimoda), a middle-schooler in a provincial fishing town, whose indie rock band draws the attention of a curious young mermaid named Lu (Kanon Tani). The mermaid’s fascinated by their music, and becomes more human the more she hears their songs: for as long as the band plays, her fish-tail becomes a pair of legs, which she uses for enthusiastic acrobatic dancing. But the town has reason (they think) to be suspicious of mermaids and the creatures of the deep. Still, when Lu joins Kai’s band, success for the group seems assured — but forces both above and below the water threaten the developing harmony.

The images here are bright and colourful, the linework loose yet clear while backgrounds remain detailed. Faces bulge and distort, pushing cartoon reality. Movement is appropriately fluid, and the whole film feels energetic, young, and vital. At the same time, it evokes atmosphere when it needs to; Kai broods, at times, and has much to brood about. Lanky, shaggy-haired, he’s a visual contrast of the brightly-coloured always-moving always-smiling Lu, and so out of the interplay of the two of them we get the movie.

The aural craft’s as solid as the visual. The alt-pop soundtrack works, which is crucial to the overall effect of the movie. The band makes good music, and the songs are used well to help drive the feel of the film — it’s not a typical musical, in which songs sum up character and plot and theme, but a movie in which music is an integral part of the story and shapes the progress of the action. More precisely, it’s not a movie musical but a movie about music, and if that still means a lot of song-based set-pieces, it’s a slightly different structure which here is executed effectively.

The tone’s relatively light overall; at least, on the light side of realism. The village feels like a real place, filled with real people with interrelated histories and class consciousness — not prominent, but there, a part of who they are. The town’s filled with subplots, too, which weave throughout the film and provide a real sense of texture to the story. The place has a history, and that history informs the action of the present, both in terms of the community and of the characters specifically. If it’s convenient for one of Kai’s band-mates, Yuuho (Minako Kotobuki) to be the daughter of a rich and powerful family, it at least plays out logically and makes sense to her overall character; it also makes her an interesting contrast to Lu, who turns out to be the scion of an equally powerful undersea family (and I’ll note that the introduction of Lu’s father is one of the best sequences in the film).

The tone’s relatively light overall; at least, on the light side of realism. The village feels like a real place, filled with real people with interrelated histories and class consciousness — not prominent, but there, a part of who they are. The town’s filled with subplots, too, which weave throughout the film and provide a real sense of texture to the story. The place has a history, and that history informs the action of the present, both in terms of the community and of the characters specifically. If it’s convenient for one of Kai’s band-mates, Yuuho (Minako Kotobuki) to be the daughter of a rich and powerful family, it at least plays out logically and makes sense to her overall character; it also makes her an interesting contrast to Lu, who turns out to be the scion of an equally powerful undersea family (and I’ll note that the introduction of Lu’s father is one of the best sequences in the film).

At the same time, there are other aspects to the setting beyond the human world. There’s an eye for nature here, in the waters and cliffs surrounding the village; there’s a sense that the merfolk fit in this world as much as the humanfolk do, but in a different way. There’s a kind of folkloric sense, perhaps, of a nonhuman natural world and also of supernatural creatures emerging out of it — which is, I suppose, the definition of merfolk, a mixture of the human and inhuman. Certainly there are rules that shape everything, that hold all these different aspects in balance. One of the most striking moments in the film is a relatively quiet sequence involving a clifftop shrine that helps explain some of the history and rules of the story; what engaged me was something in the atmosphere, in the visual sense the film uses at that moment, in the downshift to a quieter pace. The point I want to make here is that there’s a tonal complexity to Lu and her people, a deep strangeness that balances the fantastic and the realistic, and is familiar at the same time. It’s a movie that can keep different things in balance.

Conversely, the plot and some of the themes are perhaps too familiar. There’s the conflict of artistry and mass appeal, as corporate ne’er-do-wells plan to exploit Lu by way of mass merchandise and even a replacement band. There’s Kai’s largely self-imposed alienation from the rest of the group (amusingly named Seiren), and the question of whether they’ll all get back together as a group in time for the big show that can save everything. If plot development isn’t especially novel, though, it is at least well-handled — the story moves along smoothly, the pacing works, and individual set-pieces are marvellous, recalling old-fashioned bigfoot cartooning as villagers are swept up helplessly into Lu’s dance.

Conversely, the plot and some of the themes are perhaps too familiar. There’s the conflict of artistry and mass appeal, as corporate ne’er-do-wells plan to exploit Lu by way of mass merchandise and even a replacement band. There’s Kai’s largely self-imposed alienation from the rest of the group (amusingly named Seiren), and the question of whether they’ll all get back together as a group in time for the big show that can save everything. If plot development isn’t especially novel, though, it is at least well-handled — the story moves along smoothly, the pacing works, and individual set-pieces are marvellous, recalling old-fashioned bigfoot cartooning as villagers are swept up helplessly into Lu’s dance.

It’s difficult not to compare this film to Night Is Short, Walk On Girl. That movie was a story about college-age youths that seemed to come from an older perspective, celebrating a certain period in life while also knowing what lies beyond it. This movie is a children’s movie, and if it is necessarily made by adults, it lives in a tween world without feeling a need to reach beyond it or comment on what the experience of childhood is like. This doesn’t make it better or worse, really, but it does mean there’s a specific kind of texture and complexity present in Walk On Girl that’s not here.

What we do get is a solid piece of entertainment that hits its marks and has elements of strangeness around the edges. The merfolk are convincingly weird, the setting’s complex, and even the animation demonstrates an engaging willingness to move away from the strictly realistic. This is a bright, well-crafted entertainment, which is just what it aims at being.

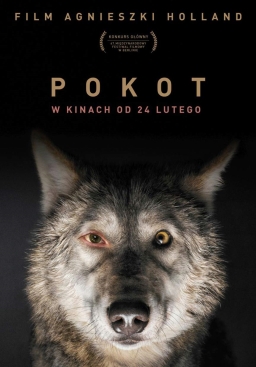

Following that came a wildly different movie, Spoor. It’s directed by Agnieszka Holland in collaboration with her daughter, Kasia Adamik; Holland, the director behind films like Europa, Europa and the 1993 adaptation of The Secret Garden (and who has lately worked on American prestige TV series, including The Wire), adapted Olga Tokarczuk’s novel for the screen in tandem with Tokarczuk. Tokarczuk’s novel was titled Prowadz swój plug przez kosci umarlych, literally “Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead,” a quote from William Blake; one of the characters (at least in the film) wants to translate Blake into Polish. The movie’s Polish title is Pokot, which Holland stated in an interview “is a hunting expression, meaning the count of killed animals. The expression is not widely known in Poland. The English-language title [Spoor] is a hunting term that refers to the trace, or tracks that animals leave, and has a similar enigmatic feeling.”

Following that came a wildly different movie, Spoor. It’s directed by Agnieszka Holland in collaboration with her daughter, Kasia Adamik; Holland, the director behind films like Europa, Europa and the 1993 adaptation of The Secret Garden (and who has lately worked on American prestige TV series, including The Wire), adapted Olga Tokarczuk’s novel for the screen in tandem with Tokarczuk. Tokarczuk’s novel was titled Prowadz swój plug przez kosci umarlych, literally “Drive Your Plow Over the Bones of the Dead,” a quote from William Blake; one of the characters (at least in the film) wants to translate Blake into Polish. The movie’s Polish title is Pokot, which Holland stated in an interview “is a hunting expression, meaning the count of killed animals. The expression is not widely known in Poland. The English-language title [Spoor] is a hunting term that refers to the trace, or tracks that animals leave, and has a similar enigmatic feeling.”

The plot concerns an old woman, Duszejko (Agnieszka Mandat-Grabka), in a small Polish town. One by one, some of the townsfolk are murdered, and she thinks she knows why: nature is turning against humanity. The animals are taking revenge, for uncounted years of cruelty and slaughter and hunting-parties. We follow Duszejko as she tries to get the authorities to take her theory seriously, at the same time as we follow her increasingly complex and unconventional personal life — a scientist fascinated by the natural world, she’s also a believer in astrology, and must balance the affections of her neighbour Matoga (Wiktor Zborowski) and a visiting entomologist named Boros (Miroslav Krobot). As the year passes, the death toll rises, and tension mounts: what is happening, and how will it all be resolved?

Although nominally a mystery that’s open to supernatural explanations, in fact it’s actually not difficult to see generally what’s happening in this movie and who’s responsible. How it will all end, though, is more difficult to predict and so the film works as a story that keeps one in suspense. It also works as an intensely atmospheric and well-told story of death and belief and political life in a small Polish town, and succeeds admirably in drawing one in to its setting.

Slowly, we come to understand there’s something like a conspiracy at work in the town. Except ‘conspiracy’ has the wrong overtones: this conspiracy’s out in the open, government officials and church officials and all men of power working together. Children are indoctrinated in the upside-down values that alienate the human world from the natural; it’s relevant that Duszejko’s a teacher, and that certain messages are passed on to the boys of the town. This is a politically-engaged and overtly feminist film that functions as a kind of parable: the behaviour we see in the town, the way that power works and force is exercised, is a kind of microcosm of the world around us. All of society is indicted in this movie. It’s about patriarchy, in a sense, or if you prefer kyriarchy: the way in which power is exercised unjustly.

Slowly, we come to understand there’s something like a conspiracy at work in the town. Except ‘conspiracy’ has the wrong overtones: this conspiracy’s out in the open, government officials and church officials and all men of power working together. Children are indoctrinated in the upside-down values that alienate the human world from the natural; it’s relevant that Duszejko’s a teacher, and that certain messages are passed on to the boys of the town. This is a politically-engaged and overtly feminist film that functions as a kind of parable: the behaviour we see in the town, the way that power works and force is exercised, is a kind of microcosm of the world around us. All of society is indicted in this movie. It’s about patriarchy, in a sense, or if you prefer kyriarchy: the way in which power is exercised unjustly.

It’s important to say that there’s nothing undramatic in the way the movie discusses politics. This is an engaging story that is inextricable from its political context, and it is a story that is driven by its characters — who are themselves also inextricable from the politics that shape their lives. The drama here develops through an increasing exposure of the layers of corruption of society; in that sense, this movie fits in perfectly with the crime genre.

It’s not to be mistaken for a noir film, though, much as it depicts a marginalised outsider seeking justice in an unjust world. There’s too epic a feel, too much lushness in the nature-imagery. Whether in snow-drowned winter or green-gold summer, this is a beautiful movie that uses light and colour in an almost painterly way — again, never falling into the trap of excessive stillness but presenting a detailed vision of the splendour of the world through which its characters move. We see the grandness of hill and valley, we see the precision of insects about the business of life.

It’s not to be mistaken for a noir film, though, much as it depicts a marginalised outsider seeking justice in an unjust world. There’s too epic a feel, too much lushness in the nature-imagery. Whether in snow-drowned winter or green-gold summer, this is a beautiful movie that uses light and colour in an almost painterly way — again, never falling into the trap of excessive stillness but presenting a detailed vision of the splendour of the world through which its characters move. We see the grandness of hill and valley, we see the precision of insects about the business of life.

For this is a movie in part about the interconnectedness of birth and death. How could it not be? It’s about the cycle of life, about nature that is red in tooth and claw. It’s about the way in which humans relate to the natural world and the ways in which humans are always a part of it, however we may try to be something else. At the same time, it’s a movie that largely revolves around elderly main characters, and indeed around their exploration of sexual freedom and open relationships; so it’s perhaps about the rediscovery of a sense of permissiveness, once beyond the conventions of an unnatural society, about people too old to care about what they should be and bent on discovering who they really are.

On a practical level, the exploration of relationships occasionally feels slightly disconnected from the murder plot. But then one can say that characterisation in the film is richer the closer to the main character we get; so this isn’t quite a standard genre piece. There are occasional convenient genre moments — I think particularly of a piece of magical computer hacking late in the film — but by and large the heart of the film lies, I think, in the range of the characters. The way Duszejko speaks differently to different people in different situations.

On a practical level, the exploration of relationships occasionally feels slightly disconnected from the murder plot. But then one can say that characterisation in the film is richer the closer to the main character we get; so this isn’t quite a standard genre piece. There are occasional convenient genre moments — I think particularly of a piece of magical computer hacking late in the film — but by and large the heart of the film lies, I think, in the range of the characters. The way Duszejko speaks differently to different people in different situations.

This is a well-observed movie that works as a genre story; as suspense more than mystery, but in any case as a narrative that catches us up and makes us wonder what will happen next. It’s also a meditative statement on power, society, and the way those things relate to the natural world. It finds a remarkable ending, credible and open to individual interpretation. It’s a fine and marvellous piece of work.

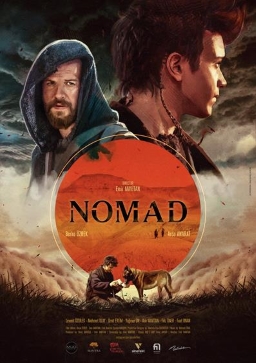

My third and last film of the day was Nomad, directed by Emir Mavitan from a script by Mavitan and Atasay Koç. It’s set in a world, perhaps in the past and perhaps in the future, that’s suffered some kind of environmental catastrophe. In this world wander a father, Baras (Berke Üzrek) and his teenaged son Karan (Arda Anarat), trying to survive in the desolation. Then after a chance encounter with another wanderer they come across a map to a settlement in a fertile place beyond the wasteland. They set off, but when they arrive the story really begins; have they found a utopia, or a deceptive trap?

My third and last film of the day was Nomad, directed by Emir Mavitan from a script by Mavitan and Atasay Koç. It’s set in a world, perhaps in the past and perhaps in the future, that’s suffered some kind of environmental catastrophe. In this world wander a father, Baras (Berke Üzrek) and his teenaged son Karan (Arda Anarat), trying to survive in the desolation. Then after a chance encounter with another wanderer they come across a map to a settlement in a fertile place beyond the wasteland. They set off, but when they arrive the story really begins; have they found a utopia, or a deceptive trap?

I wasn’t sure what to make of the movie going in, and I still can’t find any other reviews of the film in English. I have to admit I didn’t care for it. There are some strong elements here, and some solid if well-worn ideas, but also a sense of cheapness that I felt undermined the film as a whole. To me, it feels more like a TV show than a theatrical release. The lighting, particularly in the indoor and firelight scenes, is lacking in texture. Slow-motion is used too heavily, over-emphasising dramatic moments and slowing the story down. And the story’s too familiar; there’s nothing here that’s really surprising.

That said, there is a fairly solid dramatic structure to the film. The relationship between father and son is dramatised well, both the affection and the tension between them, and is ultimately pushed to a solid conclusion. It gives the film a solid core, and keeps some level of interest. The motif of two travellers in a strange land, trying to understand the place they’ve found and to work out if it’s as safe as it appears, is handled well. Generally, the writing may not be exceptionally inventive, but structures its story in a workmanlike way and does what it needs to do.

I would say that the acting is similarly solid. Baras is perhaps a little underwritten, but Üzrek’s performance tells us what we need to know about him, and creates a convincing portrait of a man who’s struggled to survive great hardship. Meanwhile, Anarat’s Karan is engagingly clever. Neither character is portrayed as simply good or bad, but they often end up at loggerheads as a function of their different ages and experience. That’s all to the good.

The problem is that there just isn’t enough development of either man; nothing surprising. That combines with the overfamiliar feel of the basic plot to create a sense that the film is more derivative than it in fact is. There’s a nagging sense that there’s nothing here that one hasn’t seen elsewhere, perhaps handled more sharply. And this is where the overall slowness of the film comes in: if it moved more swiftly, had a touch more originality in its dialogue or design sense, it likely would feel a lot stronger.

The problem is that there just isn’t enough development of either man; nothing surprising. That combines with the overfamiliar feel of the basic plot to create a sense that the film is more derivative than it in fact is. There’s a nagging sense that there’s nothing here that one hasn’t seen elsewhere, perhaps handled more sharply. And this is where the overall slowness of the film comes in: if it moved more swiftly, had a touch more originality in its dialogue or design sense, it likely would feel a lot stronger.

There is a legitimate mythic sense to the movie’s underpinning. The land laid waste by ecological disaster has the feel of both legend and the contemporary world; it’s both fantasy and science-fiction, at least potentially. Add a father-son tension to that, a primal relationship that encompasses both conflict and deep trust, and the groundwork is there for an affecting story. At the very least, this might well have made a good solid sword-and-sandal tale.

But although the story does build to a decent final conflict, there isn’t really enough movement in the plot for it to work as a pure adventure story; again, it’s too slow. It’s more successful as a parable, I think, but there’s an earnestness that keeps it from really taking flight here as well. That’s particularly unfortunate, as the slowness that drags at the film as narrative might have created a meditative sense had the pacing been approached a little more creatively. As it is, I can’t say I felt engaged with the movie at that level.

There is some remarkable cinematography here, particularly early in the film as we follow Baras and Karan in their journeys; we have some nice vistas, appropriately grand views of the barren lands they seek to escape. I did think that once they reach their sanctuary the camerawork tends to rely on medium shots, useful for getting a sense of character but somewhat abandoning the sense of a wider world.

There is some remarkable cinematography here, particularly early in the film as we follow Baras and Karan in their journeys; we have some nice vistas, appropriately grand views of the barren lands they seek to escape. I did think that once they reach their sanctuary the camerawork tends to rely on medium shots, useful for getting a sense of character but somewhat abandoning the sense of a wider world.

Nomad has a lot of potential in it, but I didn’t think that potential was really brought out. The powerful mythic themes the film hinted at, with its father-son duo wandering a waste land to reach a fertile realm housing a people with mysterious ceremonies, made for a strong set-up that never quite developed into a really complex dramatic situation — notwithstanding the script’s creditable focus on the relationship of the two main characters. It’s workmanlike, it shows potential, especially in the writing, but while its visual storytelling is competent it’s also slow and obvious. Frankly, it’s a movie I wish I could appreciate more than I did.

After the film, director Emir Mavitan came out to take questions. Asked about a scene in the village where Turkish subtitles were visible on the screen, Mavitan said that scene took place in a fictional language with its own grammar; it was important for the scene that the language sound poetic and feel magical. Asked whether it was intentional that the story could take place either in past or future, he said he wanted to base the story on ethics and moral codes — in order to reflect the story at its best, he abstracted it from religious teachings and moral thinking.

After the film, director Emir Mavitan came out to take questions. Asked about a scene in the village where Turkish subtitles were visible on the screen, Mavitan said that scene took place in a fictional language with its own grammar; it was important for the scene that the language sound poetic and feel magical. Asked whether it was intentional that the story could take place either in past or future, he said he wanted to base the story on ethics and moral codes — in order to reflect the story at its best, he abstracted it from religious teachings and moral thinking.

Asked about the development, he said it began as a short, but was expanded to a feature while trying to keep the budget the same. 55 minutes of footage were shot before the budget was used up; after seven months of trying to work out another plan, they cut a teaser from the footage they had, hoping to use it to find more backers. Someone from Turkish television saw it, and agreed to support it — on condition that they trash everything they’d done, and reshoot it from the beginning with a more generous budget. Asked about the origin of the story, Mavitan talked about being inspired by the situation of refugees from Syria in Turkey; he made it a father-son story which he hoped would be accessible.

That ended the questions, and I left the theatre, exhausted. The past three weeks of watching films were beginning to catch up to me. I had only one more day of films to go. And then the festival would be over for another year.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.