Fantasia 2017, Day 17: Futures Human and Otherwise (Attraction, “Valley of White Birds,” “Scarecrow Island,” and “Cocolors”)

There were two screenings I wanted to attend at the Fantasia Festival on Saturday, July 29. First was the Russian science-fiction film Attraction (Prityazhenie). After that was a triple-bill of animated shorts: “Valley of White Birds,” from China; “Scarecrow Island,” from Korea; and “Cocolors,” from Japan. All together, a promising day of fantastic imagery on the big screen in the 400-seat D.B. Clarke Theatre. (In addition, a long short film preceded Attraction, “Past & Future Kings”; as it happens I know some of the local creators, and so feel it would be inappropriate to write about the movie here.)

There were two screenings I wanted to attend at the Fantasia Festival on Saturday, July 29. First was the Russian science-fiction film Attraction (Prityazhenie). After that was a triple-bill of animated shorts: “Valley of White Birds,” from China; “Scarecrow Island,” from Korea; and “Cocolors,” from Japan. All together, a promising day of fantastic imagery on the big screen in the 400-seat D.B. Clarke Theatre. (In addition, a long short film preceded Attraction, “Past & Future Kings”; as it happens I know some of the local creators, and so feel it would be inappropriate to write about the movie here.)

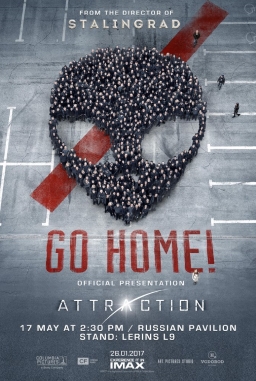

Attraction was directed by Fedor Bondarchuk from a script by Oleg Malovichko and Andrey Zolotarev. It is an epic (132 minutes, though the IMDB claims there’s a 117-minute version as well) story about an alien spacecraft that crashes into a neighbourhood in the south of Moscow. I saw a trailer before going in that made the film look like an Independence Day–like story about humans rallying to fend off an invasion; I don’t think it’s giving away a major twist to say the movie’s nothing like that at all. Instead, it’s about the Russian government trying to negotiate a first contact situation while assorted everyday Muscovites react with more or less suspicion — and one of the aliens (Rinal Mukhametov) ends up making contact with the young daughter (Irina Starshenbaum) of the army officer (Oleg Menshikov) overseeing the crash site. They fall in love, but he has to get back to his ship as the hate and fear of the humans reaches a boiling point.

Attraction has some very definite echoes of Starman and (by the end) of The Day The Earth Stood Still. Like those movies, it’s about idealism and human nature; about both the good and bad of the human condition and human emotional terrain. Like those movies, it derives tension from pitting the stupidity, fear, and violence of humans against human generosity and the human ability to love. If the result isn’t really in question, it’s a reasonably convincing trip getting there. There’s romance and action and character beats and a few laughs, and all are managed reasonably well, even if the movement from one to another can come as a swerve.

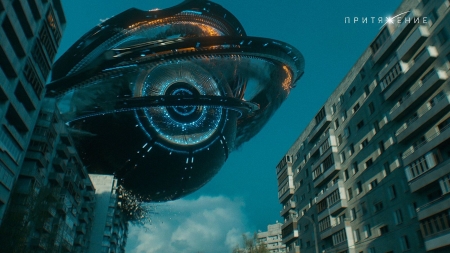

Attraction feels, in fact, quite a bit like a big-budget Hollywood movie, from its sentimentality to its production values. The CGI is excellent, and there’s a sheen of professional slickness to the visuals overall. There’s a good eye for place, too, bringing alive the Chertanovo district of Moscow, here dominated by high tower blocks and old industrial infrastructure. The aliens crash into someplace that has an identity, which goes some distance to setting up everything that follows.

Attraction feels, in fact, quite a bit like a big-budget Hollywood movie, from its sentimentality to its production values. The CGI is excellent, and there’s a sheen of professional slickness to the visuals overall. There’s a good eye for place, too, bringing alive the Chertanovo district of Moscow, here dominated by high tower blocks and old industrial infrastructure. The aliens crash into someplace that has an identity, which goes some distance to setting up everything that follows.

Most of the human characters we follow are genuinely unpleasant at first, to the point of being unsympathetic in a way that feels challenging. People were killed when the ship crashed, so a lot of our leads, most of whom are teens, are angry and afraid of the aliens. They’re given every reason to be at their worst, and contrasted with an idealistic teacher who sees the alien crash as a chance to learn something about ourselves. The story then follows the kids as some find a better angel in their nature and some don’t. It’s a good set-up, though one can argue the most visually dramatic part of the movie, the crash itself, takes up too much time; the story really only seems to begin afterward, as human and alien come into contact.

Primarily the plot follows the connection that develops between the alien Hijken and the young Yulya, as his powers are explained and she ends up teaching him about earth and humanity. That sounds standard, and in many ways it is, but what makes the story feel a little different is the rawness of the hate the humans all around them have for the aliens. There’s a constant sub-plot of anti-alien sentiment not only in the actions and mentalities of the characters but in little touches such as graffiti stating that “this is our earth.” The conflict here is not terribly sophisticated, but it doesn’t try to be. It’s about basic emotions at play, and whether one can rise above them or find some countervailing positive emotion instead. I note that according to Wikipedia, the writers have said that the film was inspired by an anti-immigrant riot in 2013, situating this movie in a longstanding tradition of using science-fiction to both address specific political situations and also find what is universal in the specific. So here the story is about overcoming fear of the other and reaching out with empathy.

There’s enough complexity in the film to mostly justify its length and keep things interesting. The Russian government is by and large a positive force, trying to enforce a perimeter around the ship and keep things peaceful, but there are enough different factions involved nothing’s all that certain. Yulya must sometimes deceive her father, and if that sounds like a standard plot point for a young-adult protagonist, here it both ties in to their established family relationship and also takes a surprising form.

There’s enough complexity in the film to mostly justify its length and keep things interesting. The Russian government is by and large a positive force, trying to enforce a perimeter around the ship and keep things peaceful, but there are enough different factions involved nothing’s all that certain. Yulya must sometimes deceive her father, and if that sounds like a standard plot point for a young-adult protagonist, here it both ties in to their established family relationship and also takes a surprising form.

The story goes through a series of assorted twists, often things likely only in cinematic terms: sneaking into a hospital, say, and then once there engaging in a medical procedure with no training. You can buy it as a genre convention, the film pushing the limits of what its YA-ish form will allow. If there’s nothing wrong with any one plot point individually, I do wish the movie had trimmed some overall — the movie feels long, if not overlong. In fact, some details suggest the excision of a subplot or two, as when rioters toward the end of the film all seem to have matching T-shirts; you wonder if there was a social movement we haven’t seen develop.

Still, all the twists do get the story to where it has to go. In this case, that’s up into space, where some quasi-religious imagery connects up with earlier dialogue paralleling space and heaven. The story itself isn’t religious, but doesn’t shy away from using Christian iconography to inform its conclusion. (Again, one thinks here of the subtext of The Day The Earth Stood Still; one wishes, in fact, that the plot had been a little less similar.) There’s nothing particularly subtle in Attraction at any point, really, and if it’s solid in aggregate, there’s also nothing essential or compelling about it. Still, it’s a competent blockbuster with some credible ideals, an attempt to entertain which largely succeeds, and that’s nothing to sneer at.

Still, all the twists do get the story to where it has to go. In this case, that’s up into space, where some quasi-religious imagery connects up with earlier dialogue paralleling space and heaven. The story itself isn’t religious, but doesn’t shy away from using Christian iconography to inform its conclusion. (Again, one thinks here of the subtext of The Day The Earth Stood Still; one wishes, in fact, that the plot had been a little less similar.) There’s nothing particularly subtle in Attraction at any point, really, and if it’s solid in aggregate, there’s also nothing essential or compelling about it. Still, it’s a competent blockbuster with some credible ideals, an attempt to entertain which largely succeeds, and that’s nothing to sneer at.

I’d return to the D.B. Clarke Theatre for a triple bill of animated shorts. According to Rupert Bottenberg, director of Fantasia’s Axis Section (dedicated to animation), as he went through the various animated films submitted to Fanatasia, he found these three movies had some startling similarities of theme and image that suggested they’d work well as a unit. “Cocolors,” the longest of the three, is 45 minutes long, which made it a difficult fit for short film showcases. Adding the 14-minute “Valley of White Birds” and 19-minute “Scarecrow Island” to it, though, created a set of films with a coherent feel and appropriate length to screen as a whole.

Director Cloud Yang’s “Valley of White Birds” was first. It’s a beautiful, colourful film about a wanderer in a golden-toned forest who follows some mysterious figures to a deserted village. A series of transformations follows, and images of white birds and fallen leaves and a strange old man and even a dragon, as the wanderer finds themself in a struggle that threatens all kinds of destruction. Will this be a story of victory, of death, or of rebirth? Will the wanderer be alienated from nature, or find a way back to harmony?

Director Cloud Yang’s “Valley of White Birds” was first. It’s a beautiful, colourful film about a wanderer in a golden-toned forest who follows some mysterious figures to a deserted village. A series of transformations follows, and images of white birds and fallen leaves and a strange old man and even a dragon, as the wanderer finds themself in a struggle that threatens all kinds of destruction. Will this be a story of victory, of death, or of rebirth? Will the wanderer be alienated from nature, or find a way back to harmony?

It’s difficult not to be reminded of Miyazaki while watching this movie, and I mean that in the best way; it’s not derivative, but the view of the natural world, and the wonder with which nature’s evoked, bring Miyazaki to mind. There’s a stillness to the film as well, a meditative sense. That’s a good trick, as a fair number of events happen here; the pacing’s handled well, then, giving us incident unfolding out of incident while also giving us enough time to ponder what we see. That’s helped by the lack of spoken words in the movie, which has no dialogue at all. At the same time, though the general course of events is clear, that lack of exposition means certain elements of what we see may be difficult to follow entirely at one viewing. The general course of events is always clear, though, and one mark of the film’s success is that I’d be happy to watch it again to work out what I was seeing.

Next came “Scarecrow Island,” written and directed by Hyemi Park. (Or Park Hye-mi, depending on your approach to transliterating names; in any event, I saw Park’s feature film Crimson Whale at Fantasia in 2015, and was privileged enough then to interview her, which you can read here.) This is a post-apocalyptic film, following a pilot who is part of a unit flying sorties against monsters who have emerged after a nuclear war and now, among dangerous radioactive storms, threaten the remnants of humanity. Then the pilot finds an island where none should exist, and on the paradisic island an old lady building scarecrows that seem to wave to him, beckoning him down. Is it real, or delusion? Does it matter? But what will the pilot do when orders come to strike at the island?

Next came “Scarecrow Island,” written and directed by Hyemi Park. (Or Park Hye-mi, depending on your approach to transliterating names; in any event, I saw Park’s feature film Crimson Whale at Fantasia in 2015, and was privileged enough then to interview her, which you can read here.) This is a post-apocalyptic film, following a pilot who is part of a unit flying sorties against monsters who have emerged after a nuclear war and now, among dangerous radioactive storms, threaten the remnants of humanity. Then the pilot finds an island where none should exist, and on the paradisic island an old lady building scarecrows that seem to wave to him, beckoning him down. Is it real, or delusion? Does it matter? But what will the pilot do when orders come to strike at the island?

The first thing you notice in “Scarecrow Island” are the colours, or that’s how it was for me coming on the heels of “Valley of White Birds.” The technological base housing the pilots is pale, grey, washed-out; Scarecrow Island is green, vibrant. It’s a direct visual image of how much has been lost. The haunting images of the scarecrows, humanlike but hollow, feels like a meaningful symbol: you don’t entirely know how much to believe of the island or of the broader setting — how much of the threat the pilots are fighting is real, and how much a creation of the authorities? How much do we know about the authorities themselves, faceless and manipulative? This is a bleak but convincing film that uses ambiguity well to create an ending that feels victorious and hollow at once. It’s a remarkable piece of work.

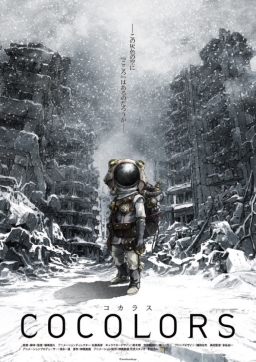

Finally came “Cocolors,” written and directed by Yokoshima Toshihisa. It takes place in a world devastated by the eruption of Mount Fuji. Survivors live deep underground, wrapped head-to-toe in survival suits. In this world we find two children, Aki (Takada Yuuki) and Fuyu (Hata Sawako). Fuyu wants to see the outside, but is too frail. Aki joins the Salvage Unit, which brings back pieces of the grey ash-coloured outside to the underworld of fire, colour, and ritual. Fuyu becomes an artist, trying to reconstruct the world as it was. But will he ever be able to imagine or recreate the colour of sky?

Finally came “Cocolors,” written and directed by Yokoshima Toshihisa. It takes place in a world devastated by the eruption of Mount Fuji. Survivors live deep underground, wrapped head-to-toe in survival suits. In this world we find two children, Aki (Takada Yuuki) and Fuyu (Hata Sawako). Fuyu wants to see the outside, but is too frail. Aki joins the Salvage Unit, which brings back pieces of the grey ash-coloured outside to the underworld of fire, colour, and ritual. Fuyu becomes an artist, trying to reconstruct the world as it was. But will he ever be able to imagine or recreate the colour of sky?

That really only scratches the surface of the drama the film creates. This is a story of blighted childhood, of children growing up in a blighted world, of young visionaries struggling to imagine something better and make their vision real. The tension and the stakes increase steadily through the film, as characters are driven to face their fears. That’s visually brought out by the suits; when they shed their protective shells we understand the finality of their choices.

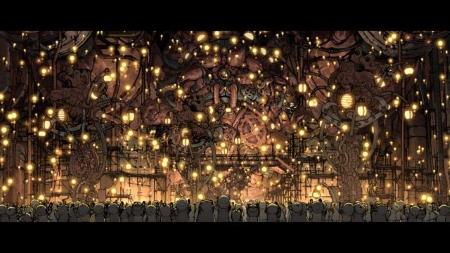

Appropriately, the colours of the underworld are rich and deep. Fuyu learns to make prints of his creations, and this film becomes to a large extent about his art; about finding colours to describe the world. The design of the underground is spectacular, engaging to look at without being somewhere you’d want to visit, never mind live in: this is a dieselpunk post-apocalypse, with hydraulics and clunky mechanisms, but also one in which atavistic beliefs are re-emerging. It’s a fascinating society to watch, in which everyone is shielded from everyone else; in which everyone has a facade that hides their emotions and true self. In that kind of a setting, the physically weak artist has an incredible power.

For all the technology of the setting, in fact, this future is wedded to dreams. Dream sequences here have an unusual effect: they make the setting more real, by establishing more fantastic alternatives. Here is the world the characters live in, and here is the one they imagine as they sleep. In fact the movie is, as I read it, in the end about the imagining of a better world. A final climb out of the depths tests the limits of vision and the real, an elegant and challenging statement about how far a creator may go for their art.

With the films completed, director Yokoshima Toshihisa of “Cocolors” and Hyemi Park of “Scarecrow Island” came out to take questions, with moderation from Fantasia’s Rupert Bottenberg. The first question from the audience asked why the three films were all fascinated with a post-apocalyptic idea (if in the first film only by implication). Bottenberg observed that when he went through the short films submitted to Fantasia, these three stood out for their intelligence and production standards, but also for that thematic link. Toshihasha described his film as a metaphor for Japan, with the masks representing the way that (he felt) at least in Japan people cannot express feelings — one may share information over the internet, but not emotions (he said he did not know how things are in Canada). Park said that this was the first time she’d seen the other two movies, but thought it was interesting how the films tied together visually as well as thematically, with white birds and helmets as recurring images. She said she had always been interested in post-apocalyptic themes, and took more specific inspiration for her film from Japanese news reports of an old woman living alone on an island making scarecrows.

With the films completed, director Yokoshima Toshihisa of “Cocolors” and Hyemi Park of “Scarecrow Island” came out to take questions, with moderation from Fantasia’s Rupert Bottenberg. The first question from the audience asked why the three films were all fascinated with a post-apocalyptic idea (if in the first film only by implication). Bottenberg observed that when he went through the short films submitted to Fantasia, these three stood out for their intelligence and production standards, but also for that thematic link. Toshihasha described his film as a metaphor for Japan, with the masks representing the way that (he felt) at least in Japan people cannot express feelings — one may share information over the internet, but not emotions (he said he did not know how things are in Canada). Park said that this was the first time she’d seen the other two movies, but thought it was interesting how the films tied together visually as well as thematically, with white birds and helmets as recurring images. She said she had always been interested in post-apocalyptic themes, and took more specific inspiration for her film from Japanese news reports of an old woman living alone on an island making scarecrows.

A couple of questions for Toshihisa followed, focussing on the practicalities of the suits of his characters and their design; he revealed that the liquid in their suits was a nutrient they used to live, and when asked how they go to the bathroom, he answered “Good question.” He explained that the characters were bonded to their suits, so they never saw faces or felt bodies directly, and even their babies were cultured in test tubes. Asked what earlier animation inspired the directors, Toshihisa pointed to Gisaburo Sugii’s adaptation of Night on the Galactic Railroad, while Park cited Mamoru Oshii and Ghost in the Shell. Asked what was next for them, Toshihisa said he hoped to do a feature, although he was finding many difficulties. Park said she was just starting her next film, about having a shadow (according to my notes).

Toshihisa was asked how large his art staff was for his project and how long it took them; per my notes, he said post-production took a year, while the ten-month main animation had a main staff of ten artists, with a total of about thirty people involved. The directors were then asked about the symbolism of the white birds in their films; Toshihisa spoke about them as a metaphor for going beyond, while Park talked about recovering utopia after having lost it. Park was then asked why the government in her story bombed the utopia at the end, and she spoke about differences in perception between her lead character and the others in the story, and how people see things but may not realise it.

Toshihisa was asked how large his art staff was for his project and how long it took them; per my notes, he said post-production took a year, while the ten-month main animation had a main staff of ten artists, with a total of about thirty people involved. The directors were then asked about the symbolism of the white birds in their films; Toshihisa spoke about them as a metaphor for going beyond, while Park talked about recovering utopia after having lost it. Park was then asked why the government in her story bombed the utopia at the end, and she spoke about differences in perception between her lead character and the others in the story, and how people see things but may not realise it.

That concluded the questions, and for me ended another day at the festival. I was impressed by the programming decision that had brought these three animated films together; they’d worked spectacularly well as a unit. And interesting too to see the contrast with Attraction, a resolutely optimistic view of human potential. It was as though things had gotten darker as the day went along. An increasingly earned darkness; one that left me intensely satisfied with the day as a whole.

(See all my 2017 Fantasia reviews here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy his first collection of essays, looking at some fantasy novels of the twenty-first century, here. His second collection, looking at some fantasy from the twentieth century, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.