I Was Paper Trained by Philip K. Dick

My oldest son Sam loves the movie Blade Runner above almost any other, and so he was at least provisionally interested when the recent and long-delayed sequel, Blade Runner 2049 hit the theaters. Myself, I didn’t care much one way or the other. I like the original movie well enough (though it’s not the touchstone for me that it seems to be for many others) but as for the sequel, well… the two hours that will forever go down in infamy as Prometheus did a lot to damage my moviegoing relationship with Ridley Scott, which was never that warm to begin with. (I know Scott was “just” the executive producer on 2049, but still. Once someone has charged you twelve dollars for the privilege of farting in your face, you don’t forget it.)

In any case, the merits of the movies are beside the point. It has long irked me, as a science fiction fan and as a father, that Sam’s enthusiasm for Blade Runner has always been untempered by any encounter with Philip K. Dick’s actual novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep? or indeed, with anything by the man who I regard as the greatest of all science fiction writers. Before you call Child Protective Services, please know that I didn’t fail in every way as a parent — Sam has a wife and a home and a job, he can tie his shoes and put together a coherent English sentence, he’s kind to animals and considerate to everyone he meets, at least until he finds out who they voted for, and he’s a hell of a cook. He’s a fine and productive person and my pride in him is unbounded… but really, c’mon — Phillip K. Dick!

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

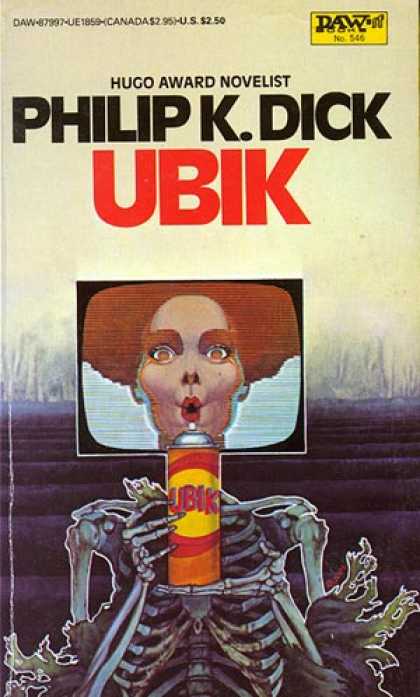

Art by Bob Pepper

There’s only so much a person can take. A few weeks ago I decided that I’d had enough, and I hopped online to buy my boy a PKD novel and present it to him with an ultimatum: “Read it, or…I have no son!” I decided to get him a copy of UBIK (Do Androids Dream is actually pretty far down on my list of PKD favorites.) I don’t think UBIK is necessarily Dick’s best novel, whatever that might mean (under torture, I would probably give that spot to Martian Time-Slip), but it’s certainly his most — I hate to use such a shop-worn term, but here it actually applies — mind blowing.

The book is in print, but I wanted Sam to have the edition that I have, the 1983 DAW paperback, with what might be my favorite cover ever, an incredible, apocalyptic image by Bob Pepper. A cheap old paperback — there’s got to be a million of them available, right? A quick consult of ABE Books revealed that actually there aren’t that many of that particular edition floating around out there and that if I wanted a fine copy, it would cost me about forty five dollars. It seems I’m not the only person to think that that’s a great cover. So… Sam can have mine when I die.

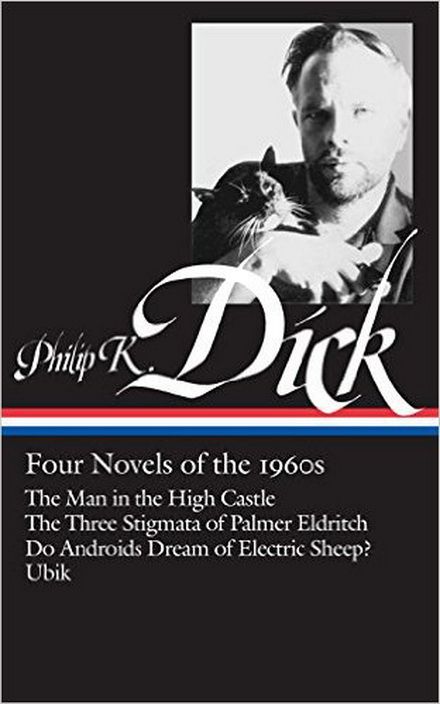

Until then, he can make do with the nice Library of America hardcover that collects The Man in the High Castle, The Three Stigmata of Palmer Eldritch, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?, and UBIK that I grabbed on Amazon for a mere twenty dollars, pausing only briefly to marvel that Philip K. Dick, of all people, has finally gotten the kind of respect and recognition that gets you into the establishment-accepted pages of the Library of America. So everybody’s happy, yes?

Mostly. Mostly. The thing is, though, that somehow I just don’t feel like Philip K. Dick belongs in a staid, conservative, (safe!) Library of America volume. It’s not that I don’t think that he belongs there in terms of his worth and importance as an American writer — just the contrary. I believe that no American writer of his time — not just science fiction writer, but no American writer, period — will prove to be of more lasting value.

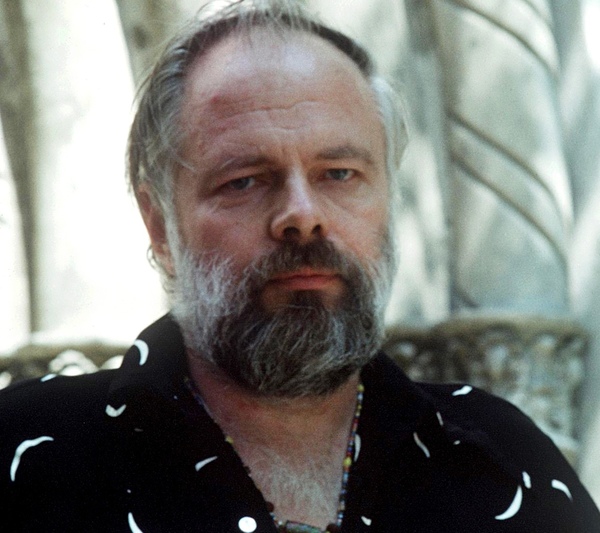

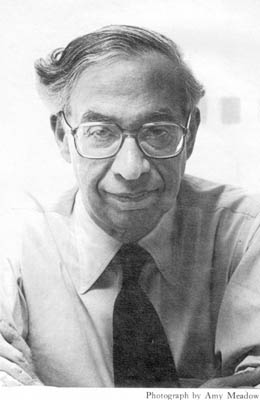

Philip K. Dick

Phil Dick damn well does belong on the same shelf with Melville and Hawthorne and Poe. The fact that he (and so many others from once-despised popular genres, people like H.P. Lovecraft, Jim Thompson, Theodore Sturgeon, Clark Ashton Smith, and Raymond Chandler, to name just a few) are now finally being recognized by whatever passes for the literary establishment these days, well… that’s good, isn’t it?

Yes. It is. It’s good that Philip K. Dick can now take his place in the pantheon right next to someone like John Updike. Of course, such prestige is a big change for Dick, who had to scrape and scramble in a literary ghetto his whole professional life; unlike Updike, he never had The New Yorker for his private prose parking-lot, though I suppose that magazine would be happy to publish a Dick story now, now that he’s dead.

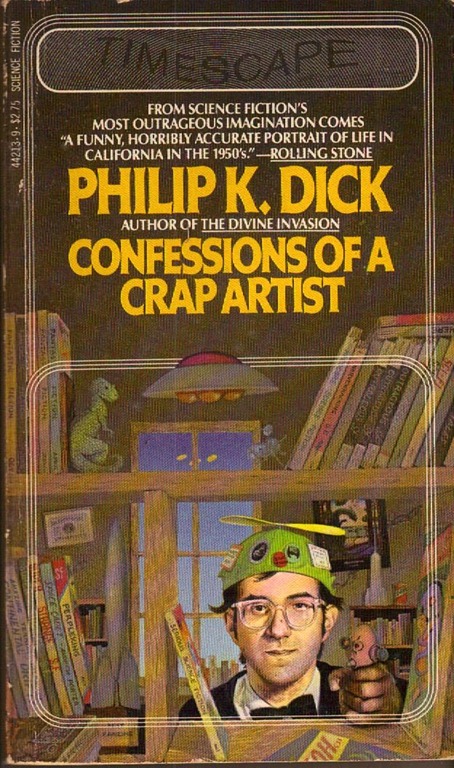

Cover by Carl Lundgren

I guess that’s the crux of the problem that I have with the new respectability these writers have found. It’s not the deeply deserved recognition, it’s the people bestowing it. Phil Dick and so many like him were starved for respect during their lifetimes (and not just for respect — the story of Dick once being so hard up that he had to buy meat that was ordinarily used for dog food is well known), and when they needed the leverage and financial compensation that only serious recognition could give them, non-genre publishers and critics were unwilling to see past the gaudy covers and breathless blurbs, the pulp science fiction or mystery or horror tropes and trappings, to the real writing underneath.

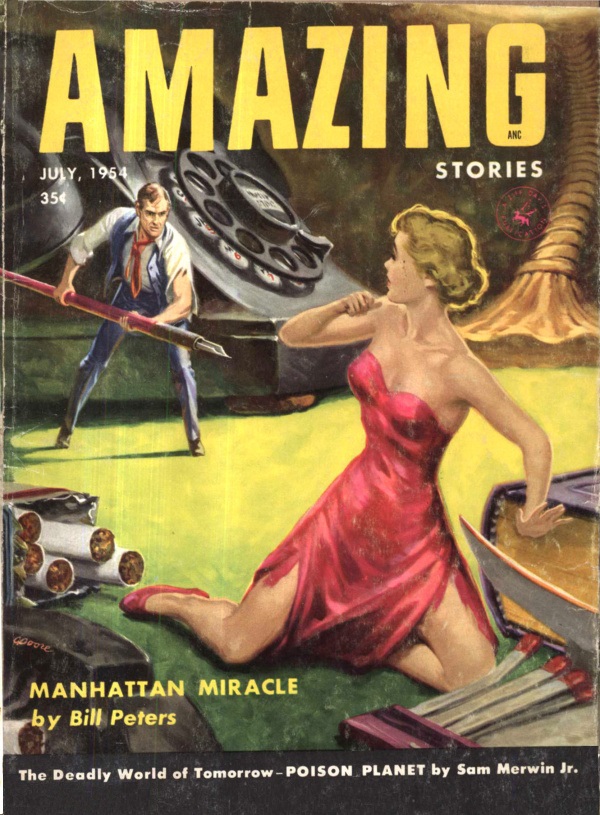

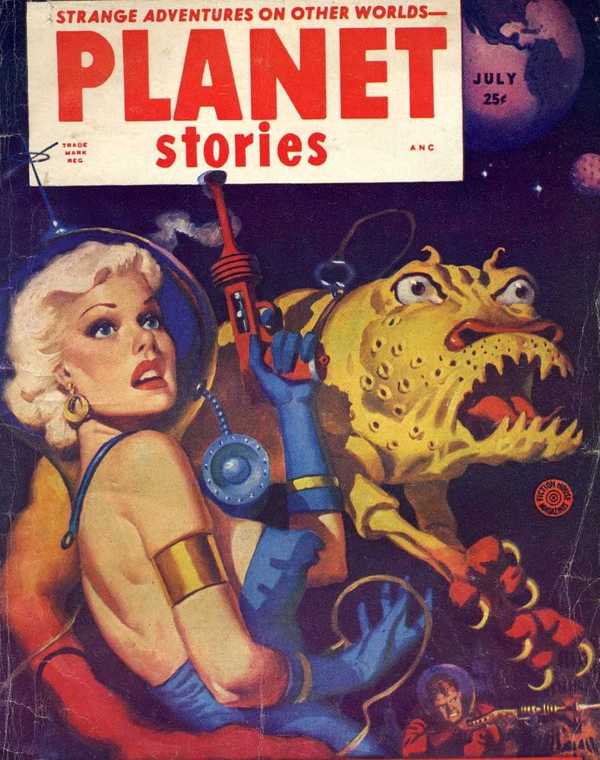

Dick tried like hell for several years to break into the mainstream market with brilliant, heartbreaking novels like Confessions of a Crap Artist. No one would have them; they knew where this guy was from. Amazing Stories (“Breakfast at Twilight,” July 1954) and Planet Stories (“Beyond Lies the Wub,” July 1952) and the rest of their ilk were toilet paper, right? And you know what you find on toilet paper.

Amazing Stories, July 1954. Cover by Clarence Doore

Planet Stories, July 1952. Cover by Allen Anderson

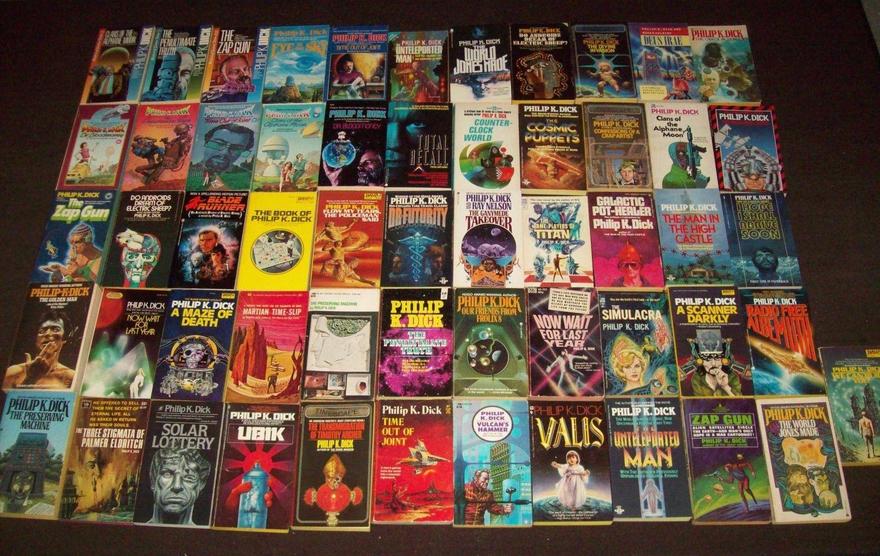

So Dick returned to the only place he could — the science fiction magazines that no serious person would be caught dead reading, the reckless, low-rent paperback publishers like ACE and Berkeley and DAW. Heaven knows they didn’t pay much, but what they did pay enabled Dick to stay alive. They didn’t get his books onto the front page (or any pages) of The New York Times Book Review, but they did connect him to a small but passionate audience that knew and appreciated and encouraged him. They couldn’t make him comfortable, but they did keep him writing — thank God. They enabled him — however precariously — to realize his extraordinary vision, and they gave us access to it.

Artists should be given the honor and the recognition (and the remuneration!) that their work deserves, and late is better than never. I’m sure that Philip K. Dick would be pleased to see the mainstream acceptance that his work — the work that cost him so much — has achieved, and I think he would be proud to be in the Library of America. But I also think that he would remember the people who kept him going before there even was a Library of America, people like Donald Wollheim, who bought so many of his books, first at ACE and then later at DAW.

Donald Wollheim

Dick dedicated his novel, Now Wait for Last Year (one of five that he wrote in 1963 — a high output was the only thing that kept the wolf from the door) to Wollheim, with these words: “To Don Wollheim — who has done more for science fiction than any other single person. Thank you, Don, for your faith in us over the years. And God bless you.” Phil Dick never stopped being grateful to all those who had helped him, and he was never ashamed of his work or of where it came from.

I have all three of the Philip K. Dick volumes that the Library of America has published. They do honor to a great writer, and I’m glad to have them and to think of what they would have meant to the man who wrote them, and of what they can mean now, to all those who still struggle to have their writing taken seriously, who strive to produce honorable, worthwhile work in genres that many still look down on. Phil Dick was the first science fiction writer to make it into the Library of America; he kicked down the door, and Ursula LeGuin has followed. You can be sure that there will be many more.

Some of Philip K. Dick’s many paperbacks

But when it comes time to read Phil Dick, I can’t help but remember the old saying, “Dance with the one that brung ya.” Then I leave the conservative clothbound volumes on their high shelf and grab myself an old paperback, cheap paper, wild cover, silly blurbs and all.

It just seems like the right thing to do.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was a review of Dead of Night.

Love this, LOVE this, LOVE THIS! Please let us know what Sam thinks when he reads something Dick wrote!

Hey, Smitty. I actually wrote up a little review when I finished “Do Androids Dream”! This post is set to public, so it should be viewable.

https://m.facebook.com/story.php?story_fbid=1721259777905422&id=100000642495392

Samuel, there’s a 14-year difference between the release of the book and the release of the film — and I wonder if that relatively short time span affected the perception of androids/AI in such a way that might lead to your comment about the sympathy Roy Batty’s ‘death’ caused you to feel, and what you refer to as ‘the capacity for effortless cruelty and manipulation’ evidenced by the androids in the novel. We’re now 35 years beyond that first film, and I have to believe that if we ever truly have anything at all like the replicants in either film, we’ll either make certain (if it’s possible) to incorporate Asimov’s 3 Laws in the manufacture of any and all androids, or we’ll need to deal with the question of rights from Day 1. The newer film has already changed my perspective, but that change has been aided as well by quite a few other films and TV programs I’ve watched and books I’ve read. I would be much more willing, I think, to advocate for rights and privileges for androids after having seen “BR 2049” than I would have after seeing the first film, but that may also be due to our current society’s altered, more progressive attitude toward equality in so many other areas of daily life.

As a retired college English professor, I was also quite impressed by the quality of the writing in your comments. I wish I were as eloquent here, but it’s a couple hours past my bedtime and I tend toward fuzziness when I’m tired…

I appreciate that, thank you very much! I had good teachers, my Old Man chief among them. It’s the stamina to produce quality consistently that I lack, something that will hopefully be remedied if I ever manage to get my carcass back into an English classroom.

It hadn’t occurred to me that changes in public perception might be reason for the difference between Electric Sheep and Blade Runner, and them again between Blade Runner and BR2049. A willingness to pause and truly consider someone (or even something) radically different and, consequently, to afford them the same dignities reserved one’s self – I would very much like to think that such a mindset is the new norm. I don’t think I believe that it is, but it’s certainly a nice thought.

You should read the kid’s Marxist analysis of The Cat in the Hat…