Three Fifths of a Great Horror Movie: Dead of Night

Well kiddies, it’s October and we’re now well launched into what John Keats called the season of mists and mellow fruitfulness and AMC calls Monsterfest Month. There’s no reason it can’t be both, is there? The whole point, you see, regardless of whether the weather is misty or not, is to read as many horror stories and watch as many horror movies as you can before midnight on the 31st while still holding onto your job (to say nothing of your marriage or other significant relationships).

The stories are no problem — as Black Gaters in good standing, I’m sure you all have shelves that are sagging under the weight of countless horror anthologies, so chilling choices abound. The movies pose a different problem, however. While you can read a good story in twenty or thirty minutes, a movie requires a commitment of an hour and a half or more. So at this overbusy time of year, why not increase your fright efficiency and watch a movie that gives you three, four, or five stories in one sitting?

Horror anthology movies used to be quite common. American International Pictures did some in the early sixties featuring Vincent Price (of course — I think AIP must have had the poor man chained in the basement) — 1962’s Tales of Terror (Poe stories, because studios like nothing so much as an out of copyright author) and 1963’s Twice Told Tales (this time Nathaniel Hawthorne was the writer receiving no royalties), and Amicus Productions (a kind of poor man’s Hammer, if you can imagine such a thing) specialized in them in the late sixties and early seventies, cranking out Dr. Terror’s House of Horrors (1965), Torture Garden (1967), The House that Dripped Blood (1970), Tales from the Crypt (1972), Asylum (1972), and The Vault of Horror (1973). You don’t see this kind of film so much anymore, though their memory is kept alive by the umpteenth yearly iteration of The Simpson’s Treehouse of Horror.

The House

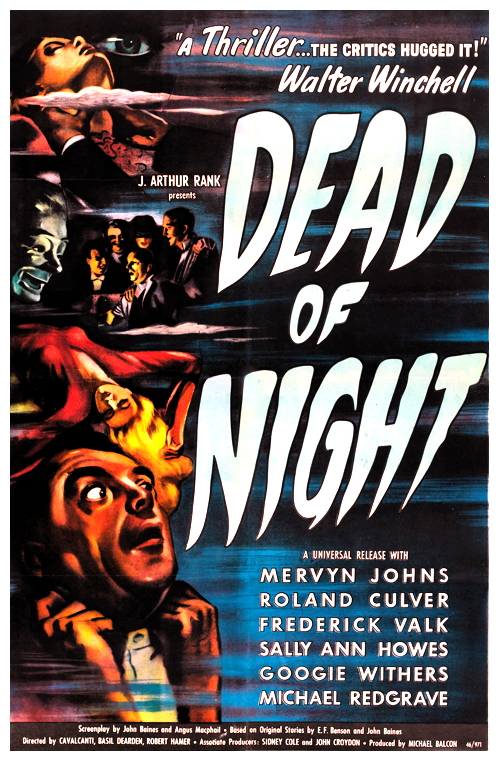

The granddaddy of them all, though, is a legendary movie more often talked about than seen, 1945’s Dead of Night, produced by Britain’s Ealing Studios, an outfit best remembered for delightfully nasty comedies like The Ladykillers and Kind Hearts and Coronets. Taking stories by H.G. Wells, E.F. Benson, and themselves, screenwriters John Baines and Angus MacPhail linked them with a frame story and along with the four different directors employed on the project produced a film that can still reward the patient viewer with some genuine shivers.

The film begins with architect Walter Craig (Mervyn Johns) driving up to a country house in Kent. He has been invited for the weekend on the prospect of taking a job remodeling the house, though he doesn’t personally know anyone who lives there. Nevertheless, as he meets the owner and his other guests, Craig is overpowered by a feeling of deja vu. He tells them that this is because he has a recurring dream in which they all figure, and which always ends in nightmare. He even makes several predictions about what will happen that evening — the arrival and departure of various people, the breaking of a pair of glasses, and so on. All this is dismissed as nonsense by one of the guests, Dr. Van Straaten (Frederick Valk), a psychiatrist whose Teutonic accent is as impenetrable as his rationality is unshakeable.

Over the course of the evening, five of the guests, spurred on by Craig’s bizarre story, relate strange experiences of their own. Race car driver Hugh Grainger (Anthony Baird) recounts something that happened during a hospital stay after a racing crash. Near the end of his convalescence, he feels inexplicably compelled to get out of bed and go to the window of his upper-storey room. Though it’s ten at night, his bedside clock suddenly reads four fifteen, and outside it is full day. Parked directly beneath his window is an old fashioned horse drawn hearse. The driver looks up at him and cheerily says, “Just room for one inside, sir.” Grainger turns away and walks back to his bed. By the time he gets there, the clock has returned to the right time and the vision has passed. Grainger chalks it up to a lingering trace of delirium and within a week he’s discharged from the hospital with a clean bill of health.

Mervyn Johns

As he walks down the sidewalk to catch a bus, a stranger asks him the time — it’s a quarter after four. A bus pulls up and when the doors open, the ticket taker says, “Just room for one inside, sir,” and Grainer, seeing that the man is the hearse driver of his vision, steps back and the bus drives away without him. When it reaches the end of the street, it swerves to avoid another vehicle and plunges down an embankment, killing everyone on board. End of story. This is the shortest of the movie’s episodes and though it’s done well enough, it’s so brief it feels like a teaser, an anecdote rather than a genuine story.

Next, teenager Sally O’Hara (Sally Anne Howes), tells of a fright she got during the previous year’s holidays while she was staying at a large old country house. Sally hears in passing from the schoolmate who lives there that the house has an evil history — eighty five years before, a young boy was murdered there by his jealous sister. Later, during the course of a Christmas party game of hide and seek, Sally hears a child crying. She searches, and the sound of weeping leads her to a door concealed behind a wardrobe. Opening it, she finds the child — a little boy who says his name is Francis Kent — sitting in a nursery. Assuming Francis is another houseguest like herself, she comforts him, sings to him, and tucks him into bed. She then slips out of the room and rejoins the other party goers, who have been searching high and low for her. On telling them where she was and who she was with, she discovers the truth — Francis Kent was the little boy who was murdered so many years before and the sealed nursery was the room where it happened. Sally has spent her evening cuddling with a ghost.

This episode (which bears a strong resemblance to A.M. Burrage’s classic ghost story, “Smee”) is not as effective as it should be, mostly because it feels rushed. Paradoxically, when the payoff is known almost from the beginning, the careful development of the story becomes even more important. In this case, however, it seems as if the filmmakers decided that since everyone would know where this tale was headed, the point was to get there as quickly as possible and be done with it. It’s too bad, because this kind of story can give you a real tingle when it’s done properly (as in the aforementioned “Smee”). Also, it must be said that at the age of fifteen, Sally Anne Howes — while a lovely young lady and a decent enough actress — had an extraordinarily annoying voice. (She had apparently grown out of it by the time she played Truly Scrumptious in Chitty Chitty Bang Bang, twenty three years later.)

The Child’s Ghost

For all their failings, these first two stories at least succeed in setting the grim, doom laden mood that will dominate the rest of the movie — with one regrettable exception.

The next episode is one of the strongest in the film, as Joan Courtland (Googie Withers) relates the almost fatal disaster that ensued when she bought her fiancé Peter (Ralph Michael) an antique mirror for a birthday present. He’s delighted with the gift, but before long whenever he looks in it, he sees a completely different room reflected in its glass, a room from a previous era, with a large four poster bed and a blazing fireplace, a room that seems to beckon to him. Even worse, if Joan should be standing in front of the mirror with him, he can’t see her reflected in it at all. (Joan of course can never see anything unusual in the glass.) At first, by force of will, Peter can make the false image disappear, but soon loses this ability, and begins to fear that he’s going insane. Equally alarmed, Joan goes back to the shop where she bought the mirror to learn something of its history.

The shopkeeper tells her that over a hundred years before, it — and a four poster bed that he still has in the shop — belonged to a strong willed man of violent temper who was severely injured in a fall from a horse. Rendered a virtual invalid and largely confined to his bed, his always volatile temper turned to outright paranoia. He began to accuse his faithful and loving wife of all manner of infidelities, and eventually strangled her and immediately afterwards sat in front of the mirror and cut his throat. Joan hurries home to tell Peter, but when she arrives, she finds that he’s no longer the man she knows — he’s now the homicidally jealous husband who lives in the mirror. Peter seizes her and starts to strangle her, and as Joan struggles her eyes fall on the mirror; for the first time she sees the evil room reflected in it, the room that she will die in — unless she can break the spell. Desperately reaching out, she manages to grab a lamp stand and with it she breaks both the glass and the mirror’s hold over Peter, who comes to himself as one awakening from a dream, remembering nothing.

The Evil Mirror

Mirrors figure in much supernatural fiction as they do in much superstition — who doesn’t feel that there’s something inherently sinister about them? (If you don’t, good for you — they creep the hell out of me.) This episode in Dead of Night often pops unbidden into my mind when I wake at three a.m. and makes me hesitant to get out of bed to do my business (I have to walk past a mirror to reach the bathroom) and for me, that’s a horror story’s test of tests. The unhurried pace in this section is a big plus, as the excellent Ralph Michael is able to show us the gradual change that comes over Peter as the mirror gains control of him. Unlike the previous episode, the payoff here has real force because it’s been properly prepared for, and Joan’s first and final glimpse into the hellish room is wonderfully startling and scary, as if in that moment its evil is reaching out to claim them both.

Having built up considerable momentum with the story of the haunted mirror, Dead of Night almost fumbles it away with the penultimate story, a comic tale of two golfing buddies who play a round to determine who gets the girl they both love. (This arrangement is perfectly fine with her, which is the most outré and unbelievable thing in the whole movie.) Upon losing, Larry Potter (Naunton Wayne) commits suicide by calmly waking into a lake just off the 18th green (they had agreed that the loser would “disappear forever”), but quickly comes back as a ghost when he discovers that his buddy Basil (George Parratt) had cheated. Apparently in the afterlife, strict records are kept of everything, even golf scores. The phantom Larry now devotes himself to the twin tasks of getting Basil to renounce the girl and ruining his golf game. This section seems to take forever to meander its way to its less than riotous conclusion. Leaden pacing aside, a comic interlude is just what the movie doesn’t need and even if it did, it shouldn’t be asking too much to require that a comic interlude be, well… funny. In any case, the whole story belongs in a different movie.

Death on the Links

At this point, Dead of Night could charitably be called a draw, but it fully recovers and finishes strong with its most famous episode, a tale of an evil ventriloquists’ dummy to beat all evil ventriloquists’ dummies, related by Dr. Van Straaten, who was called in to examine the unfortunate ventriloquist Maxwell Frere (Michael Redgrave) after he had been arrested for attempted murder. As the story begins Frere is playing in a Paris nightclub when an American ventriloquist, Sylvester Kee (Hartley Power) drops in to catch his act. Sylvester immediately sees that the man is brilliantly talented… and also that something is seriously wrong. Frere’s dummy, Hugo, seems not to be fully in the ventriloquist’s control, but Sylvester naturally assumes that this is simply part of the act, even when Hugo invites him backstage for a talk after the show. When Sylvester knocks on the door of Frere’s dressing room, Hugo invites him in and starts a conversation about ditching his “boss” and starting a new act with him…until Frere comes in from the bathroom, seemingly unaware that Sylvester had even come in. How did Frere get Hugo to talk — from another room? A neat trick for sure, but more than a little odd. As the two ventriloquists chat, Hugo interrupts and asserts that he’s the one who’s really in charge and again tries to convince Sylvester to take him away. Frere gets very agitated and tries to silence Hugo by putting his hand over the dummy’s mouth. At this point Sylvester decides that his colleague is seriously disturbed and leaves, but before he closes the door he sees that Hugo has bitten Frere’s hand hard enough to draw blood.

Some months later in London, Sylvester again encounters Frere in the bar of a hotel where they are both staying. Frere is drunk, and after he gets pummeled by the date of a woman Hugo insults (the dummy is on the barstool right next to his owner) Sylvester helps him up to his room. Frere tries to explain his predicament; looking at a picture of Hugo, he says, “You’d drink too if you were in my shoes; I’ll tell you, it’s enough to drive a man mad.” Sylvester still doesn’t understand. He puts a barely conscious Frere to bed, sets Hugo (who has been silent through all this) at the foot, and goes to his own room. Later that night Frere bursts into Sylvester’s room, looking for Hugo. Sylvester denies that he took the dummy — as we know he didn’t — but Frere finds him hidden underneath a blanket. (In the grip of his delusion, Frere must have put Hugo there himself…mustn’t he?) Sylvester is dumbfounded, but Frere pulls out a gun and shoots his rival — not fatally, as we later see.

Now in prison, Frere pleads that Hugo be restored to him. Dr. Van Straaten persuades the authorities to do this, believing that it is only from the dummy’s lips that he will hear the truth. The psychiatrist stands outside the cell door and eavesdrops on Frere and Hugo as they have their final conversation.

“I knew you wouldn’t leave me, Hugo — I knew you’d come back.” But Hugo is having none of it. “Not for long, my boy, not for long.” Frere is going to be in jail for “years and years and years and years,” so the dummy will need a new partner, and he hears that Sylvester is recovering nicely. Frere threatens to tell the police the truth — that Hugo made him shoot Sylvester. “Try it and see what happens,” Hugo retorts. “They’ll put you in the madhouse. But not little Hugo — oh no. I’m going to team up with Sylvester. Maybe we’ll come visit you — you know; private show for the loooooniiiies.” At this, Frere snaps; he grabs a pillow and starts to smother the dummy. Hugo’s terrified screams rouse Van Straaten to call the guards, but they can’t get into the cell before Frere has thrown Hugo to the floor and stomped his head into powder.

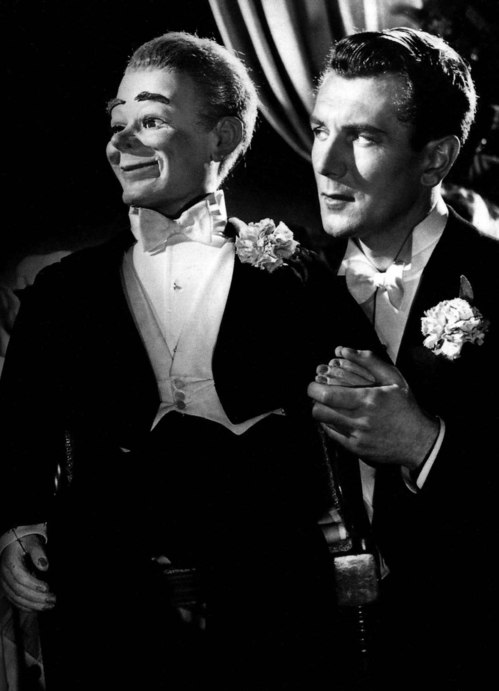

Michael Redgrave and Hugo

The final scene of the story has Dr. Van Straaten and a limping, bandaged Sylvester visiting Frere in the prison hospital, seeking to rouse him out the near catatonia in which he’s languished since destroying Hugo. When they enter the room, Frere lies motionless and limp on the bed… just as a dummy does before the ventriloquist picks him up. When Sylvester greets him, Frere’s head slowly swivels in his direction, his mouth drops open in a rigid, ghastly smile, and the voice of Hugo floats out: “Why, hello Sylvester — I’ve been waiting for you.” Fifteen years later Psycho would end similarly but, in my opinion, not as powerfully, and frightening as Norman Bates is, Maxwell Frere’s descent into madness is even more terrifying. Norman’s mother was at least a human being.

This tale of a mad ventriloquist (or a live, demonic dummy — a tiny bit of room is left for a non-psychological interpretation) is one of the most chilling things in the history of movies, and that’s chiefly due to the brilliance and commitment of its lead actor. Several other performers in Dead of Night do very well — Googie Withers, Ralph Michael, Mervyn Johns, Hartley Power — but as Maxwell Frere, Michael Redgrave is beyond all praise, and his final scene with Hugo is, within its small compass, one of the most extraordinary performances ever put on film. To see the agony and terror in Frere’s eyes as his ventriloquist’s mouth subtly shapes the evil words issuing from Hugo, the very words that are destroying him, the very words that are stripping him of his last scrap of sanity, is to be filled with the “pity and terror” that only the highest art can elicit. Redgrave is absolutely fearless (much of his last scene with Hugo is shot in extreme close-up), and he makes you feel as if you are witness to a terrifying mystery, and gazing into the darkness at the very bottom of a tortured, tormented soul. (Credit must also be given to John McGuire, who supplied Hugo’s taunting, evil voice.) Without this final story, Dead of Night would be a borderline failure, a hit and miss enterprise with as many misses as hits; with it, Dead of Night is a masterpiece — flawed certainly, but a masterpiece.

The final tale being told, the terminal phase begins. Dr. Van Straaten breaks his glasses as Craig predicted, and when everyone else leaves the room, Craig, feeling that he no longer has a will of his own, follows his growing compulsion and strangles the almost blind and helpless psychiatrist. As soon as this is done, Craig is instantly plunged into a kaleidoscopic, phantasmagoric whirlpool of nightmare which blends elements of all the tales that have been told and which ends with him backed into a corner of Frere’s jail cell, with Hugo sitting opposite. As Craig crouches, paralyzed with fear, Hugo slowly stands up and walks toward him; Craig’s mind begins to give way as the leering mannequin places his hands on the architect’s throat and starts to strangle him…

Hugo

And then the telephone rings and Walter Craig wakes up. His wife comes in the bedroom and asks, “Darling, whatever is the matter?” He wearily replies, “Another nightmare.” She answers the phone and gives it to him. It’s someone who wants him to drive down to Kent for the weekend to take a look at a possible renovation job. Craig flips a coin to see if he will go — heads he goes, tails he stays. It comes up heads (as it always has, as it always will, forever and forever and forever), and the final scene of the film is the opening scene, with the doomed Craig driving up the road and getting his “first” look at the house; a puzzled, bemused look passes across his face. It somehow seems familiar…

Walter Craig is trapped in an endless nightmare in which every waking is only a dream of waking and suffering is infinite because endless.

Is that scary enough for you?

The Final Nightmare

Like all anthologies, some parts of Dead of Night are stronger than others, but three of the six episodes (counting the frame story as an episode in itself) are fully successful, two can be rated as partial successes, and only one (the silly golf story) is totally worthless. All in all, and considering the outstanding quality of the sections that fully succeed, Dead of Night deserves its reputation as one of the great horror films. The only problem is getting an opportunity to see it. I know of no currently available version (the 1977 Dan Curtis TV movie of the same name can be had for a pittance, but that’s probably all it’s worth.) My copy is a 2003 Anchor Bay DVD edition that came out in a two disc set with another fine, eerie British film, the 1949 Queen of Spades. This set occasionally turns up on eBay; it’s worth keeping an eye out for. Otherwise, this time of year your best bet is probably to keep a close watch on AMC or TCM. The movie is well worth your time, even if you have to stay up late to see it, even if you have to stay up all the way into the… um, Dead of Night.

Just one thing — if after seeing it, you find yourself lying in your bed in the wee hours needing to get up and go to the bathroom, but reluctant to do so because you have to walk past a mirror… well, don’t blame me. You’ve been warned.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was How I Spent My Summer Vacation.

Congratulations! When I first started reading your article, here in the UK, it was still pitch black. Remembering scenes scared me so much, I had to skip over bits. That’s because I remember watching the film for the first time when I was much younger, and being scared silly by it. It’s especially the framing story that terrifies me. I’ll go back later and read the rest of the article.

It took some time after that first viewing before I found out what the film was called, so as soon as I saw it released on tape I snatched it up. Then, later, I got the DVD edition you mention as it was the only one available. As I had a multi-system setup by then (multi-format VCR, region-free DVD, NTSC-capable TV) playing a R1 disc was no problem. I’m not sure the converse is true, so letting you know that there is both a DVD *and* what appears to be a restored Blu-Ray here in the UK won’t be of much use to you. (In fact, I think I’ll go and buy that BD edition now.)

I agree that it’s the framing story that’s the most scary, with the most remembered story about the ventriloquist coming a close second. I even like the comedic story, which seems quite naughty for its time in what it implies.

Incidentally, have you seen another UK film from the same era? It’s called “The Halfway House”, released a few years earlier, in 1943 and directed by Basil Dearden (who directed the framing story and the first tale in “Dead Of Night”), with Cavalcanti as Associate Producer. It’s nowhere near a scary movie, but then I think that in the UK at that time real life was scary enough. It’s about a group of disparate people all staying on holiday at a Welsh inn called the Halfway House. (Don’t believe the IMDB synopsis or even the precis on the DVD cover – there’s no storm.) The landlord and his daughter (played by Mervyn Johns again and his real-life daughter Glynis Johns) are very warm and affable. However, they don’t appear to cast shadows or be visible in mirrors! Unfortunately for you there is also another role for Sally Ann Howes. If her voice irritates, then just listen to Glynis Johns. She has one of the most beautiful voices ever.

I’m glad I sparked a pleasantly frightening reminiscence, Stuart. I can’t remember when I first saw the movie, but I found it both frightening and deeply disturbing – not always the same thing. It’s a shame that more people (especially here in the U.S.) don’t know it.