The Complete Carpenter: The Thing (1982)

If you’re a fan of the career of director John Carpenter, you probably have an idiosyncratic favorite among his pictures. The one that has special meaning for you, possibly because of nostalgia, a particular theme, or sheer rewatchability. I’ll telegraph ahead in this series and mention that In the Mouth of Madness is one of those special Carpenter films for me. Looking backward, Assault on Precinct 13 is the Carpenter movie I’m mostly likely to rewatch, and it rises in my estimation each time I return to it. One of my close friends is deeply in love with Big Trouble in Little China, and his wife roots hard for Christine. Carpenter’s catalog has a range of minor-league wonders, and I can’t feel upset for anyone picking offbeat choices. I’ve even heard stimulating defenses of The Ward, which (spoilers for future reviews) I think is Carpenter’s worst film.

If you’re a fan of the career of director John Carpenter, you probably have an idiosyncratic favorite among his pictures. The one that has special meaning for you, possibly because of nostalgia, a particular theme, or sheer rewatchability. I’ll telegraph ahead in this series and mention that In the Mouth of Madness is one of those special Carpenter films for me. Looking backward, Assault on Precinct 13 is the Carpenter movie I’m mostly likely to rewatch, and it rises in my estimation each time I return to it. One of my close friends is deeply in love with Big Trouble in Little China, and his wife roots hard for Christine. Carpenter’s catalog has a range of minor-league wonders, and I can’t feel upset for anyone picking offbeat choices. I’ve even heard stimulating defenses of The Ward, which (spoilers for future reviews) I think is Carpenter’s worst film.

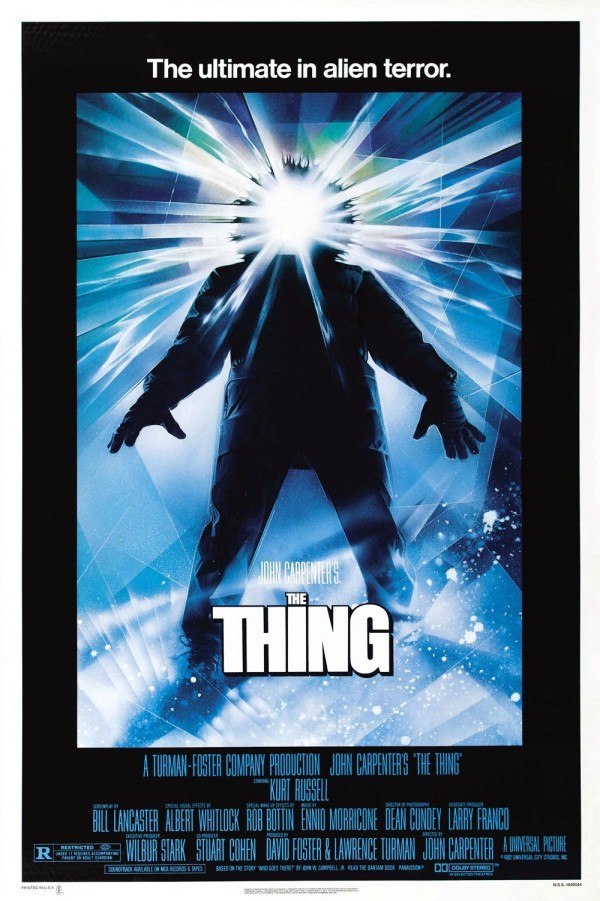

However, general consensus says 1982’s The Thing — a remake of the 1951 SF classic The Thing from Another World by way of its source material, John W. Campbell’s 1938 novella “Who Goes There?” — is John Carpenter’s masterpiece. And general consensus is right.

The Story

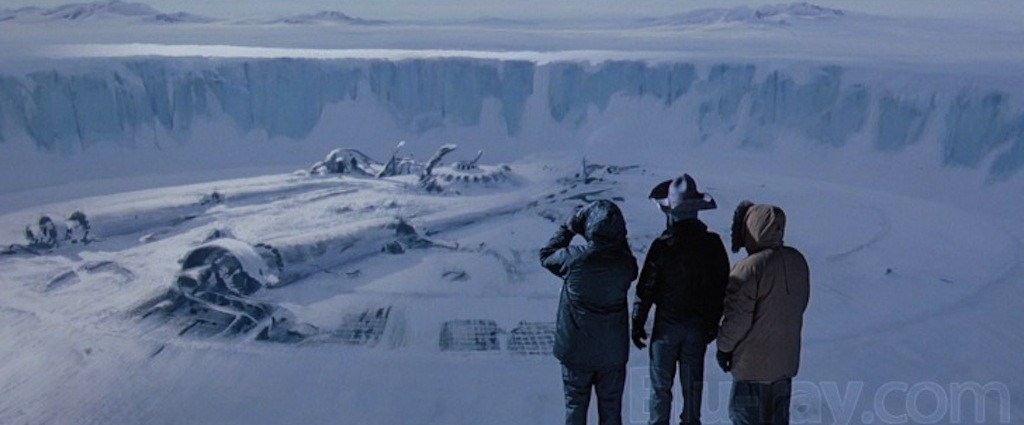

It’s the first week of the winter-over at US National Science Institute Station 4 (aka Outpost #31) in the Antarctic interior. It doesn’t start well. A helicopter from a Swedish Norwegian base makes an explosive landing at the outpost while trying to gun down a runaway sled dog. The men at the outpost take in the dog and try to figure out what happened, although failed radio communications make it difficult. They investigate the Norwegian base and discover it devoid of life with signs of a horrific violent event. It seems the Swedes Norwegians dug up and thawed out an alien lifeform from a spaceship trapped under the ice pack for thousands of years, and that didn’t turn out that swell for them.

Oops, too late … That adorable sled dog allowed into the US station is actually the alien, which can alter its shape and assimilate other organics while perfectly imitating them on the outside — and it’s started in on the men at Outpost #31. Paranoia and alien transformation freakiness break out. If it takes them over, then it has no more enemies, nobody left to kill it. And then it’s won. World assimilation in 27,000 hours after first contact with civilized areas.

For an alternative story breakdown, here’s a swingin’ succinct summary, baby! Watch those hands, Doc, ouch!

The Positives

John Carpenter’s The Thing may end up the best movie I ever write about at Black Gate. That’s not because I don’t believe there are movies its equal, just that those movies are unlikely to come up as topics or as part of my general plan for what I post here. (Hey, if our readership wants to hear my panegyric to Barry Lyndon, I’ll oblige. I’m pretty sure they don’t.)

To answer the question, “What makes The Thing ‘82 work so well?” the best response is, “Pretty much everything. Where do you want me to start?” This is a movie suited to lengthy essays on specific details: the effect of the Antarctic setting, the film’s similarities and differences to its written source material and the 1951 adaptation, the visual effects design work, the concept of identity, etc. The movie is a bottomless well for numerous analytical approaches. A general overview of The Thing feels like sprinting through the Metropolitan Museum of Art and screaming, “Hey, look at that!”

To answer the question, “What makes The Thing ‘82 work so well?” the best response is, “Pretty much everything. Where do you want me to start?” This is a movie suited to lengthy essays on specific details: the effect of the Antarctic setting, the film’s similarities and differences to its written source material and the 1951 adaptation, the visual effects design work, the concept of identity, etc. The movie is a bottomless well for numerous analytical approaches. A general overview of The Thing feels like sprinting through the Metropolitan Museum of Art and screaming, “Hey, look at that!”

Further complicating brief analysis is that The Thing ‘82 is something of a confounding film. Superficially, much of it shouldn’t work — not by the accepted standards of filmmaking, specifically the way it leaves the characters devoid of spelled-out backstories or motivations aside from survival. The Thing makes aspiring screenwriters take a hard look at that tower of screenplay how-to books beside their keyboards and then want to tumble it right into the wastepaper basket. The Thing presents an enigma of brilliance because it manages to work on all conceivable levels while doing numerous things outwardly wrong. There’s no finer example of the rule that geniuses don’t need to follow the rules.

However, there are ways to break down The Thing into some of its best elements. For the purpose of a general overview, I’ll concentrate on three superlative aspects: the atmosphere of paranoia, the suspense, and the special effects. There’s overlap, because in such a tightly knit film, talking about one is also talking about the others.

From the opening (following a prologue showing an alien ship making Earthfall in prehistory), viewers are plunged into isolation. A white vastness where the only sign of life is a single dog trailing a path through the snow. As we later discover, this is not a dog, but the alien creature of the title. We’re on a patch of Earth apparently devoid of its own lifeforms, and as far as our POV is concerned, this might as well be the entire planet. This establishes a world of physical and emotional vacuum, into which the most powerful of all emotions intrude: paralyzing fear and anxiety.

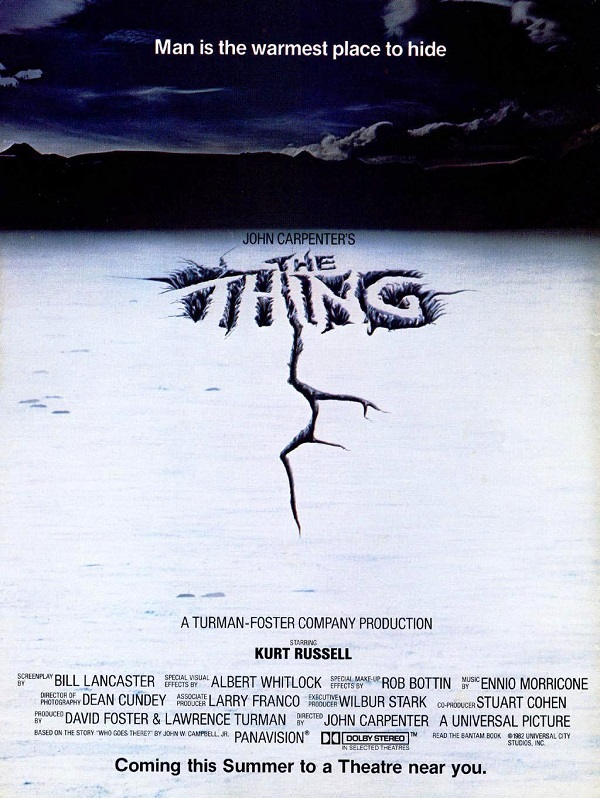

The Thing has many similarities to Alien (1979): people trapped in an isolated location fighting a stealthy, aggressive alien lifeform that has biologically infiltrated their space. But the similarities plaster over a major thematic difference between the two movies. Alien uses sexualized imagery and places its terror in twisted images of penetration, birth, and grotesque motherhood, with an alien design suggesting violent, mechanized sexuality. The Thing, on the other hand, takes the Twilight Zone approach of the terror of identity crisis: “Who — or what — is the person beside you?” As the poster tagline warns, “Man is the warmest place to hide.” The greatest enemy is the illusion of humanity.

The aura of paranoia works in tandem with one of the film’s most remarkable feats: a cast of characters who are fascinating despite viewers knowing nothing about their lives beyond their actions at the outpost. The actors invest their parts with personality that makes backgrounds unnecessary for the basic task of telling the characters apart. Protagonist and station pilot R. J. MacReady (Kurt Russell) first appears playing chess with a computer. He thinks he’s close to winning the match, but when the computer pulls a surprise checkmate, he calls the machine a “cheating bitch” and pours whiskey into the motherboard, shorting it out. Right there, we know all we need to about MacReady. He strategizes, but he’s not perfect at it. He doesn’t like to lose. He drinks too much. And he’ll torch the property if he damn well feels like it, hinting that he’s likely to be one of the final survivors. (And, indeed, he torches the place to “win” against the Thing, even though it means he’ll die afterward.)

The aura of paranoia works in tandem with one of the film’s most remarkable feats: a cast of characters who are fascinating despite viewers knowing nothing about their lives beyond their actions at the outpost. The actors invest their parts with personality that makes backgrounds unnecessary for the basic task of telling the characters apart. Protagonist and station pilot R. J. MacReady (Kurt Russell) first appears playing chess with a computer. He thinks he’s close to winning the match, but when the computer pulls a surprise checkmate, he calls the machine a “cheating bitch” and pours whiskey into the motherboard, shorting it out. Right there, we know all we need to about MacReady. He strategizes, but he’s not perfect at it. He doesn’t like to lose. He drinks too much. And he’ll torch the property if he damn well feels like it, hinting that he’s likely to be one of the final survivors. (And, indeed, he torches the place to “win” against the Thing, even though it means he’ll die afterward.)

This character shorthand used for MacReady appears with the rest of the Outpost #31 crew. Radio operator Windows (Thomas Waite) wears sunglasses indoors while staring blankly at his equipment, unable to communicate with anybody else in the emptiness of the world. Fuchs (Joel Polis) shows the most scientific caution and concern, which may explain the quick thinking to immolate himself before he could be Thing-assimilated. Nauls (T. K. Carter) is the young kid who roller skates on the job and doesn’t take his assignment too seriously. Palmer (David Clennon) is a stoner whom nobody else takes seriously. Garry (Donald Moffat) wants to be an impressive leader and is itching to use his gun at some point, and he’s known Bennings for a decade (this is the most backstory anybody gets). Childs (David Keith) is fast to anger and has something against MacReady. Sled dog handler Clark (Richard Masur) is soft-spoken and only relates well to the dogs.

Behind all these men lurks the question: why did each choose to do a winter-over in Antarctica? It’s a lonely job in the most hostile terrestrial environment on the planet. These men are either fleeing something or believe the rest of the world has nothing to offer them. Combine this with the character tics and the across the board excellent performances and there’s no need to spell out anything for viewers. The characters work even though Screenplay 101 wisdom says they shouldn’t.

The absence of character specifics makes the identity paranoia more acute. Who are these people, really? In fact, are they really people? Both the audience and the characters throw the same suspicious glances at the crew of Outpost #31 as the tension starts to ratchet up, wondering if we know enough about any of them to say for certain, the way MacReady does in the mid-film moment when the danger turns explicit, “I know I’m human.”

The absence of character specifics makes the identity paranoia more acute. Who are these people, really? In fact, are they really people? Both the audience and the characters throw the same suspicious glances at the crew of Outpost #31 as the tension starts to ratchet up, wondering if we know enough about any of them to say for certain, the way MacReady does in the mid-film moment when the danger turns explicit, “I know I’m human.”

One of the criticisms I had about The Fog was the hash of questions it leaves hanging. With The Thing, purposeful ambiguity shows what it can do: numerous questions are left behind, but none interferes with the movie as it runs, and they contribute to discussion of it afterward. Was Palmer or Norris the first person the Dog-Thing assimilated? (I.e. whose shadow was on the wall?) At what point was Blair assimilated and how? Did Fuchs burn himself up to prevent an attack by the Thing, or was it an accident? What happened to Nauls in the finale? Was the figure seen running to the generator Childs or Blair? Why was the Thing on the crashed spacecraft in the first place and what was its purpose — passenger, prisoner, bio-weapon, infiltrator, pilot? What exactly happened at the Norwegian base? (Ignore this; everybody else does.) Is Childs a Thing at the end? These are the right types of questions a film like this should leave unanswered; they contribute to the ambiance of paranoia and fear and provide fuel for late-night dorm debates.

(Here’s another one: When Norris-Thing refuses to take over command when offered — “I’m just not up to it” — is that the Thing using a diversionary strategy, or is the Norris-Thing not 100% aware it’s an assimilation and is using Norris’s memories too effectively? You can get a thesis paper out of diving into the nature of identity on that question alone.)

After the success of Halloween, Carpenter was pegged as a master of suspense and an up-and-coming Hitchcock disciple, a description he wasn’t fond of since he saw himself more in the melodramatic mode of Howard Hawks and John Ford. But he could handle suspense brilliantly, and The Thing contains a number of sequences that are all-timers for shredding viewers’ nerves: A nearly frozen and desperate MacReady threatening to dynamite everyone, leading right to the gnarly defibrillator VFX sequence. The tense stand-off with the gun over the blood bank and who had access to it. Fuchs following a shadow into the Antarctic night and finding … (?) MacReady, Garry, and Nauls making the final run to dynamite the camp when they don’t know the location of the Blair-Thing.

But it’s the blood-test scene that takes the top prize. MacReady devises a test to scare out the Thing from its current skin-sack hiding spot by sticking blood samples from each of the men with a hot wire. Arguably the best scene Carpenter ever shot, it’s a masterclass in pacing, editing, characters in conflict, and careful misdirection that jacks the paranoia to a fever pitch. Like the best suspense scenes, it still works even the hundredth time you see it.

But it’s the blood-test scene that takes the top prize. MacReady devises a test to scare out the Thing from its current skin-sack hiding spot by sticking blood samples from each of the men with a hot wire. Arguably the best scene Carpenter ever shot, it’s a masterclass in pacing, editing, characters in conflict, and careful misdirection that jacks the paranoia to a fever pitch. Like the best suspense scenes, it still works even the hundredth time you see it.

As for the visual effects … It feels silly to point out the magnitude of brilliance of the practical transformation effects by Rob Bottin’s team (with help from Stan Winston, who handled the kennel sequence) achieved through prosthetics, robotics, makeup, and air bladders. The Thing is the reference point for the power of practical VFX work and one of the first bullet points under lists of “Why Visual Effects Are Works of Art.” Even if The Thing failed in other aspects, the effects would still hold a special place in history. And who doesn’t love the stunner when the Thing turns Norris’s stomach into a set of giant teeth that tear Copper’s arms off? Now that’s showmanship!

Yet the parade of extreme effects came under attack from film critics in 1982. (Well, everything in the film did. It was a critical and box office failure.) Here’s one sample, from David Ansen at Newsweek: “There’s a big difference between shock effects and suspense, and in sacrificing everything at the altar of gore, Carpenter sabotages the drama.” The general tone of the critical reception to the VFX was that they were a betrayal of the “less is more” approach old school horror analysts consider sacrosanct.

I want to burn this old sacred cow to cinders with a blowtorch. I am a huge fan of the liminal, understated, and implied in horror. The original Cat People and The Haunting are among my favorite horror movies. But horror is not a monolith, and sometimes more is more. The subtlety of The Haunting and The Witch vs. the gonzo bloodbath of Evil Dead II and Dawn of the Dead — there’s a right approach for each film, no absolutes. The Thing ‘82 takes the right approach with its extravagant alien gore scenes filled with popping bones, stretching bodies, splitting heads, distorted skin, whipping tentacles, and slime-dripping limbs.

The technology existed in 1982 to show explicitly a non-humanoid alien capable of rearranging organic tissue in real time. The VFX team put it on full display because it makes the horror palpable. Carpenter and the actors create the tension of “who isn’t who they appear to be?” in one part of the film; then at key moments Bottin and Co. bring in the on-screen shocker of what it means to be inhuman. This is how lavish and gory effects can be used at their best, visually grabbing the audience and paying off the suspense. The gore is not gratuitous: it’s the outer explosion of the queasy inner fear that an inscrutable alien entity is hiding beside you in the skin of someone you think you know.

The technology existed in 1982 to show explicitly a non-humanoid alien capable of rearranging organic tissue in real time. The VFX team put it on full display because it makes the horror palpable. Carpenter and the actors create the tension of “who isn’t who they appear to be?” in one part of the film; then at key moments Bottin and Co. bring in the on-screen shocker of what it means to be inhuman. This is how lavish and gory effects can be used at their best, visually grabbing the audience and paying off the suspense. The gore is not gratuitous: it’s the outer explosion of the queasy inner fear that an inscrutable alien entity is hiding beside you in the skin of someone you think you know.

Listen to Garry’s bewilderment after the Bennings-Thing reveals itself, which is the first transformation the men of Outpost #31 see: “MacReady, I know Bennings. I’ve known him for ten years. He’s my friend.” To which MacReady answers, “We’ve gotta burn the rest of him.” Garry can’t believe Bennings could be anything other than Bennings, even though we witnessed his complete inhumanity only the scene before. MacReady has already moved on: torch the damn thing (ah, there’s Mac with his short-out-the-computer strategy again), it’s not human. And, well, MacReady knows he’s human.

Kurt Russell is awesome. But you knew that. Over and out.

The Negatives

Aside from the sad way both critics and audiences dismissed the film back when it came out? We can partially blame the success of E.T. and its friendlier alien lifeform for that. Did you know that Blade Runner came out the same weekend as The Thing? And Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan also came out that month? Man, 1982 … those were the days.

For years I felt a bit disappointed Carpenter used only a fraction of the score Ennio Morricone composed for The Thing. Carpenter selected a handful of cues (mostly “Humanity” and “Desolation”) and then wrote a few extra tracks with Alan Howarth. The complete Morricone score, which was released as an album, contains some astonishing and bizarre minimalist cues. However, the film works with the score “as is,” and with much of the unused Morricone music ending up in The Hateful Eight — for which the composer at last won an Oscar — this barely counts as a complaint at all. Download the complete score and enjoy it as a depressing/weird concept album.

The Pessimistic Carpenter Ending

Macready and Childs, the two “survivors” of the Thing’s attack, sit in the ice and swap swigs of whiskey as they watch Outpost #31 incinerate. They’ll freeze to death in the Antarctic wastes soon after the credits are done. Maybe one of them is the Thing. Maybe neither is. Maybe the Earth has been temporarily saved. Who cares … pass the whiskey and be glad you won’t spend the rest of the winter tied to this f*#%ing couch!

Next: Christine

Ryan Harvey is one of the original bloggers for Black Gate, starting in 2008. He received the Writers of the Future Award for his short story “An Acolyte of Black Spires,” and his stories “The Sorrowless Thief” and “Stand at Dubun-Geb” are available in Black Gate online fiction. A further Ahn-Tarqa adventure, “Farewell to Tyrn”, is currently available as an e-book. Ryan lives in Costa Mesa, California where he works as a professional writer for a marketing company. Occasionally, people ask him to talk about Edgar Rice Burroughs or Godzilla in interviews.

I had forgotten that Carpenter also directed Christine. Looks like another one for my Netflix queue …

I prefer Big Trouble in Little China myself, but the man’s talent is undeniable.

Excellent article for one of the all time best films. I especially appreciate the call out to Mac’s disdain of the Swede/Norwegian label. We occasionally have issues with a $17,000 printer at my work due to a Norwegian OS. I always take advantage of these situations to say ‘F—–g Swedes’ and I am delighted when IT corrects me with ‘Norwegians’.

About Morricone’s music, I read that when Carpenter recruited him for the job, Morricone gave him a couple of samples of how he could do it. One was a romantic score that Morricone secretly preferred, and the other was Morricone just doing an imitation of Carpenter’s musical style. Carpenter of course picked the latter.

Yes, you’re dead right about movies having a special meaning for many viewers. In my case, it concerns the late actor Charles Hallahan. For years after my girl friend and I saw this movie, we referred to him as “the head” every time we saw him in a movie or on TV, because of what happens to him in THE THING!

@dolphintornsea – Heh, I’ve had this exact same conversation a few times while watching movies with friends:

Me: Oh, look, it’s Charles Hallahan.

Friend: Who?

Me: You know, “defibrillator guy” from The Thing.

Friend: Oh, yeah! That guy!