Analog, November 1971 and October 1972: Two Retro-Reviews

|

|

John W. Campbell died in July 1971. He had been editor of Astounding/Analog for 34 years. His name appeared on the masthead through December of that year, along with remaining editorials. Presumably Kay Tarrant did the work necessary to keep the magazine going, possibly, some suggest, even buying new stories, until the new editor was chosen. Ben Bova took over officially with the January 1972 issues. (Rumor has it that Charles Platt, of all people, was one of those considered for the job; a more obvious possibility was Frederik Pohl, who said he was asked to apply. [He had left Galaxy at about this time, and was as I recall editing books for Bantam.])

So I thought I’d consider an issue from the end of Campbell’s tenure, and one from the beginning of Bova’s: November 1971 and October 1972.

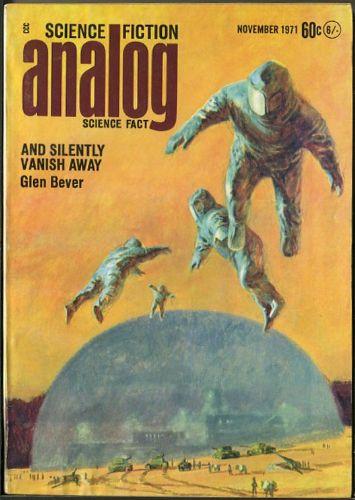

The November 1971 issue has a cover by John Schoenherr. Interiors are by Schoenherr, Kelly Freas, and Leo Summers. Campbell’s editorial, his second-last, was called “The Gored Ox,” in which he inveighs against the press’s desire to print anything they want (inspired by the Pentagon papers). The Science article is by Margaret Silbar, who contributed 16 pieces of non-fiction to Analog between 1967 and 1990. It’s called “In Quest of a Humanlike Robot.”

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

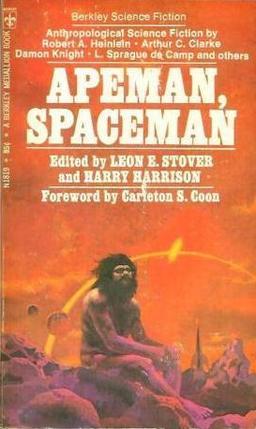

P. Schuyler Miller’s Book Review column, The Reference Library, begins with discussion of a poll he conducted (with Michael Shoemaker) concerning the best SF stories pre-1940. The winners were two by Campbell himself, “Who Goes There?” and “Twilight,” both great stories to be sure. He reviews John Lymington’s The Nowhere Place, A. E. van Vogt’s Quest for the Future, and the Leon Stover/Harry Harrison anthology Apeman, Spaceman. His highest praise is reserved for the latter.

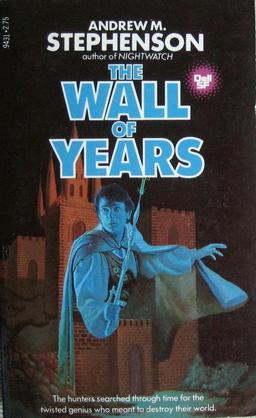

Finally, the letter column, Brass Tacks, is devoted to memories of John Campbell, from Isaac Asimov, Eric Frank Russell, Greg Bear (who at this time had only published one very obscure story, and some art), Maydene Crosby, Andrew M. Stephenson (of whom more later), Manfred Zitzman, and E. Lawton Thurston, Jr.

The stories:

Serial

Hierarchies (Conclusion), by John T. Phillifent (17,300 words)

Novelettes

“And Silently Vanish Away,” by Glen Bever (15,000 words)

“The Old Man of Ondine,” by Terrence MacKann (9,400 words)

Short Stories

“Compulsion Worse Confounded,” by Robert Chilson (47,00 words)

“Holding Action,” by Andrew M. Stephenson (6,200 words)

“The Nothing Venireman One,” by W. Macfarlane (4,000 words)

I reviewed the book version of Hierarchies some years ago as part of my series of Ace Double reviews, here. It was paired with Doris Piserchia’s Mister Justice (see below).

Hierarchies is a light-hearted piece about a King-Emperor on another planet who hires the hero to remove the “Crown Stones” from his planet, in order to promote a more democratic future. Phillifent was the real name of the writer perhaps better known as “John Rackham” – his work for Analog was under his real name, but his other work was almost always as by “Rackham.”

The two novelettes are by “Little Known Writers.” Glen Bever published four stories in the SF magazine, between 1971 and 1978 (two in Analog, one in Galileo, and one in Asimov’s.) I read at least two, and have no memory of them. “And Silently Vanish Away” is an almost perfect example of a late Campbell story. It’s set in a chemical company which has discovered a formula which gives rats the ability to teleport. This is a problem, not just because rats start showing up everywhere, but because the government becomes very interested. The protagonist is the company president, who (with the help of a sympathetic General and of course his employees [including a tall, nubile, red-headed secretary who throws herself at him in an unconvincing subplot]) manages to find a way to prevent the government from taking over, and also to prevent enemies from stealing the formula. For a while it threatens to be bouncy fun, but it founders on the scientific silliness and the blatant wish-fulfillment aspect of the main idea. (This last reeks of pandering to Campbell’s main hobbyhorse.)

Terrence MacKann is even less known than Glen Bever. In fact, this story is the only evidence of his existence I can find on the internet. The name could be a pseudonym – or he could just be a guy who only managed to published one story and otherwise led a quiet, normal, life.

“The Old Man of Ondine” isn’t too bad, really. Ondine is a colony planet of Earth, which has determined to avoid the ecological mistakes that ruined the home planet. Josun Pace is an administrator faced with solving whatever problems pop up. His biggest problems this particular day (besides the contamination of a fishing factory’s output with some poisonous fish) are the appearance of a certifiably insane man who cannot be identified, and a crashed spaceship that might represent an ecological disaster. Pace visits him (partly because his nurse is an incredibly sweet and beautiful young woman, and in standard Analog style, Pace and she get together…), and he is indeed violently insane for short intervals. Alternate sections follow the madman’s history – he was a spoiled young man visiting Ondine who messed up his spaceship… could there be a connection with the spaceship crash? It’s immediately obvious what other SF trope is involved, and the resolution, though a bit far-fetched, is rather nicely handled. Not a great story by any means, but decent enough work.

“The Old Man of Ondine” isn’t too bad, really. Ondine is a colony planet of Earth, which has determined to avoid the ecological mistakes that ruined the home planet. Josun Pace is an administrator faced with solving whatever problems pop up. His biggest problems this particular day (besides the contamination of a fishing factory’s output with some poisonous fish) are the appearance of a certifiably insane man who cannot be identified, and a crashed spaceship that might represent an ecological disaster. Pace visits him (partly because his nurse is an incredibly sweet and beautiful young woman, and in standard Analog style, Pace and she get together…), and he is indeed violently insane for short intervals. Alternate sections follow the madman’s history – he was a spoiled young man visiting Ondine who messed up his spaceship… could there be a connection with the spaceship crash? It’s immediately obvious what other SF trope is involved, and the resolution, though a bit far-fetched, is rather nicely handled. Not a great story by any means, but decent enough work.

The short stories are from a better known set of writers. Robert Chilson, as it happens, is someone I know personally, though not terribly well – he lives near Kansas City, and we’ve talked a few times at ConQuest. He began publishing in 1968, with “The Mind Reader” in Analog. He has published a great many short stories since then, with Analog and F&SF his primary markets. (He had a story in each last year.) He published as by “Robert Chilson” for about the first decade of his career, and mostly as “Rob Chilson” since then. He has also published some seven novels.

“Compulsion Worse Confounded” is about an IT person, as we’d say now. Raleigh is in charge of the “Archimage,” a cluster of seven computers that does the processing for Wilder and Wilder, a food company. But the computer is acting up. For one thing, it wants to fire the secretary (who is, natch, beautiful, and who, natch, wants to get together with Raleigh – this is Analog, after all). It also is ordering the company to acquire a rival – but the rival seems to be doing something foolhardy. Is Wilder and Wilder’s computer behind that, as well? A fairly amusing story, turning on the computer’s inability to understand human desires, and its rather literal interpretation of orders.

Andrew M. Stephenson is a British writer (though born in Venezuela) who also worked as an illustrator. “Holding Action” was his first short story. He has only published four stories (the last in 1997), plus two novels and the script for a graphic story. I really enjoyed his second novel, The Wall of Years (1979), an intricate time travel story (sharing some themes with “Holding Action”), and I was disappointed when he more or less disappeared after that. “Holding Action” is pretty decent, thoughtful, work, about a team charged with meeting time travelers and making sure they can’t return to the past and mess up the timeline… of course, there’s a history behind all this.

I’d seen the title “The Nothing Venireman One” before, and could never figure it out. W. (for Wallace) Macfarlane (1918-1999) published about 30 SF stories, the first in 1949 but the great bulk between 1968 and 1977. At his peak he had a mild reputation, appearing in a couple “Best of” books, publishing stories in Analog, Galaxy, Orbit and other places. I’ve found his work pretty interesting on occasion.

This story, however, is mildly disappointing in that context. Earth is concerned that another planet is abrogating at trade treaty, trying to enforce a huge price raise. The local Ambassador and his assistant, a Venireman Five, have no success resolving things, until an unprepossessing man, a “nothing,” who turns out to be a Venireman One, shows up, and starts acting unconventionally. This is a familiar trope, and it can be entertaining, and this story starts out OK, but in the end the Venireman One’s scheme isn’t involved enough, or surprising enough, and the story just kind of peters out.

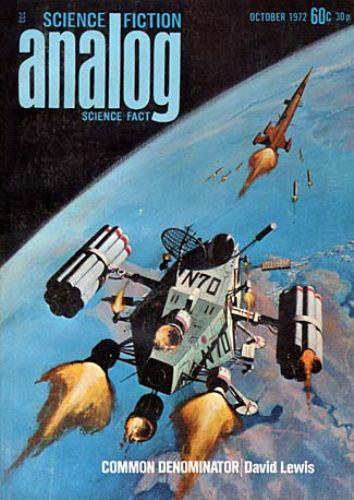

Almost a year later, we get a Jack Gaughan cover, and interiors by Gaughan, Schoenherr, Freas, Summers, and Vincent di Fate. Ben Bova’s editorial, “The Revolutionaries,” suggests that science and technology are the real revolutionary forces in our world.

Almost a year later, we get a Jack Gaughan cover, and interiors by Gaughan, Schoenherr, Freas, Summers, and Vincent di Fate. Ben Bova’s editorial, “The Revolutionaries,” suggests that science and technology are the real revolutionary forces in our world.

The Science article is by Thomas Easton, another name familiar to me from my Analog science reading – he ended up doing about a dozen articles, but this was his first, indeed his first appearance in the field. He also eventually took up the book review column, and he has published quite a lot of fiction. Like the Silbar article (which it references), it’s about robots, called “Robots – RAMs from CAMs,” and it suggests that the path to developing fully autonomous Robots could start with things like waldos and powersuits.

Miller’s Reference Library begins by covering two “mainstream” SF novels that had just been reviewed in The New York Times, Mutant 59: The Plastic Eaters, by Kit Pedlar and Gerry Davis, and The Report from Group 17, by Robert C. O’Brien. The Times had hated the first and liked the second, and Miller’s opinion was the opposite.

The novel I remember is the Pedlar/Davis, though O’Brien (real name Robert Leslie Conly) is far better known, mainly for his excellent children’s novel Mrs. Frisby and the Rats of NIMH (which won the Newbery), but also for Z for Zachariah.

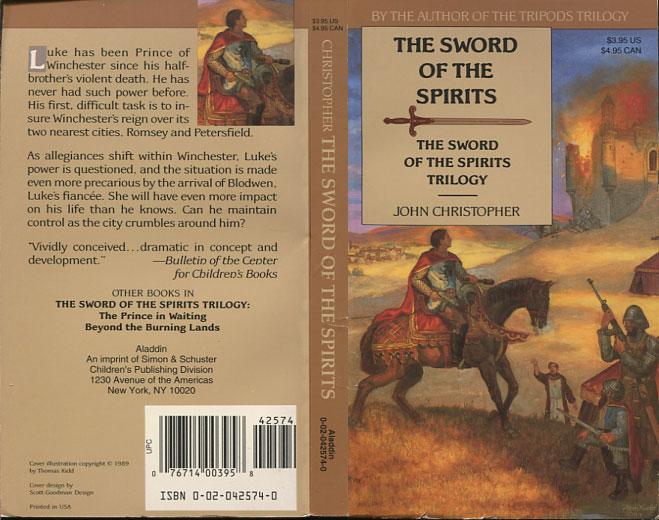

He also reviews Harry Harrison’s Tunnel Through the Deeps (which had just been serialized in Analog), John Christopher’s The Sword of the Spirits, and two by James Blish: …And All the Stars a Stage and Midsummer Century. He likes all of them except Midsummer Century (too short is one complaint), and his favorite is the Christopher (which is very good, a dark YA fantasy).

Brass Tacks features letters from Howard G. Thurston, Buzz Dixon, Leigh Couch, C. E. Deckard, Erwin S. Strauss, and Danny Low. The only name I immediately recognized is Strauss, a very famous fan better known as Filthy Pierre; though Buzz Dixon seemed familiar, and a quick search suggests he’s probably the writer for comic, films, and most notably TV cartoon shows.

OK, on to the stories:

Serial

The Pritcher Mass (Conclusion), by Gordon R. Dickson (19,500 words)

Novelettes

“Common Denominator,” by David Lewis (20,000 words)

“The Star Hole,” by Bob Buckley (10,000 words)

Short Stories

“To Be a Champion, Merciful and Brave,” by Richard Olin (3300 words)

“The Vietnam War Centennial Celebration,” by Ralph E. Hamil (5700 words)

“Stretch of Time,” by Ruth Berman (2900 words)

I read The Pritcher Mass a long time ago in book form. I don’t remember it all that well – it’s about a project to build a structure using telekinesis to search for planet to colonize, as Earth is a mess. I can’t say much more about it – Dickson in this period was a pretty reliable adventure writer, I will say, and The Pritcher Mass, perhaps more ambitious than just “adventure,” was as I recall enjoyable – but I don’t recall much more.

I read The Pritcher Mass a long time ago in book form. I don’t remember it all that well – it’s about a project to build a structure using telekinesis to search for planet to colonize, as Earth is a mess. I can’t say much more about it – Dickson in this period was a pretty reliable adventure writer, I will say, and The Pritcher Mass, perhaps more ambitious than just “adventure,” was as I recall enjoyable – but I don’t recall much more.

David Lewis published 7 SF stories between 1969 and 1981, with one more following in the very small press magazine Beyond Centauri in 2011. “Common Denominator” was his second story. It’s about an ace star fighter pilot who is part of an expedition to drive the enemy “Tars” from a contested planet. It’s not so much about the war, however, as about the relationship between the hero and his wingman, who seems to be stone jerk, if perhaps a skilled pilot. Things come to a head during the battles for superiority in Near Planet Orbit… our hero (and his wingman) are crucial to winning, but at the end he purposely passes up a chance to kill the enemy ace, knowing that the battle is over. That infuriates his wingman, who goes on to commit a treasonous act of astonishing evil, leading to one more battle, showing with whom our hero really has a “common denominator.” It’s not badly written – indeed, I found it an exciting and involving story — but it’s one of those stories that really isn’t science fiction (instead of calling a rabbit a “smeerp,” Lewis calls a fighter plane a space fighter, etc.), and it also turns on an action by the bad guy that seems beyond the pale for his established character, slimy as it is.

That said, the great military SF writer David Drake (who writes much more than Mil-SF, but that’s what’s most relevant here) remembers the story very well, and writes “I was blown away by “Common Denominator” [reading it at the time of its first appearance], and, directly to the last point I made, and drawing on his own (then very recent) experience in Vietnam, also notes

I was more willing to accept the behavior of the wingman… Insane, insanely evil behavior in a war zone is more common in war zones than any civilized human being would want to know.

Which makes an important point – to me – I shouldn’t be so sure I know realistic behavior in contexts I’m unfamiliar with. It does, however, come to the author to convince the reader of any story of that stuff – and I do think that Lewis didn’t really sell me – it occurs to me that Drake, in his Hammer’s Slammers stories for example, has shown examples of “insanely evil” behavior in a war zone that I did believe. All in all, Lewis was, on the evidence of this story, a writer with some potential, but as with many new writers, life or something intervened, and his career never really developed.

Bob Buckley was a regular of sorts in Analog between 1970 and 2004, publishing 16 stories and one serial there. He has only one other SF credit according the ISFDB, and that was in Omni in 1981, when Ben Bova was editor. I remember him as a fairly typical Analog writer of the time, often enjoyable, rarely better than that. “The Star Hole” is set on the Moon. An accident leads to several deaths when a sort of huge sinkhole opens up. That seems strange, on the Moon, and Laris Howard wants to investigate further, but the penny-pinching colony leader refuses to authorize this. So he does it on his day off (with an older scientist and a predictably perky, pretty, and obsessed-with-Laris young woman), and they discover something really strange: “star wisps” that appear to be alive. But the colony leader, and his slimy assistant, refuse to believe, and are ready to send Howard back to Earth, until they manage to figure out what the “wisps” really are, which is actually kind of cool.

Richard Olin was the pseudonym of Hugh Leddy. He published 6 stories, split evenly between Analog and F&SF, between 1963 and 1978. “To Be a Champion, Merciful and Brave,” is an ecologically concerned story, with the hero, a Native American, working on a whale research ship on the electronics. He realizes that the whales they are studying are at risk of swimming right into danger from whalers, and, disgusted, he programs some equipment to chase the whales away… which gets him fired, but that’s alright, because in the process he has realized his true calling is back with his people, fighting to keep their land from overdevelopment. It’s not bad, if over-obvious and a tad preachy.

“The Vietnam War Centennial Celebration” is the only story Ralph E. Hamil published in the field. It’s a somewhat implausible story, telling of a decision in the middle of the 21st century to commemorate the Vietnam War, because this was the war that caused people to realize that war was terrible, and thus to once and for all stop fighting. There is some bureaucratic foofaraw about setting up the exhibits, with a cynical conclusion where we realize that humans are back at war again. (I couldn’t figure out if we were to take the implication that the Centennial Celebration caused this.)

Finally, Ruth Berman’s “Stretch in Time” is about an Italian woman on the moon, who seems to be either a postgrad or a young professor, and who has discovered a means of time travel. The harried Department head investigates, and finds out she’s right – but there’s a pretty dangerous sort of side effect. It’s a pretty clever and enjoyable little piece.

Are there any obvious differences between the early Bova issue and the late Campbell issue? I would say – not so much, yet. I suppose Campbell might have been unlikely to publish Hamil’s anti-Vietnam War story, though he could surprise one. In general, the political viewpoints of the stories in Bova’s issue are more upfront than in Campbell’s, and a bit more to the left than one expects for Campbell, but this is a very small sample size, and I can’t draw any real conclusion. (It should also be noted that Bova may still have been using some of Campbell’s inventory – in at least one case, though, I confirmed with Ruth Berman that Bova had bought her story (and even asked for a revision).)

Are there any obvious differences between the early Bova issue and the late Campbell issue? I would say – not so much, yet. I suppose Campbell might have been unlikely to publish Hamil’s anti-Vietnam War story, though he could surprise one. In general, the political viewpoints of the stories in Bova’s issue are more upfront than in Campbell’s, and a bit more to the left than one expects for Campbell, but this is a very small sample size, and I can’t draw any real conclusion. (It should also be noted that Bova may still have been using some of Campbell’s inventory – in at least one case, though, I confirmed with Ruth Berman that Bova had bought her story (and even asked for a revision).)

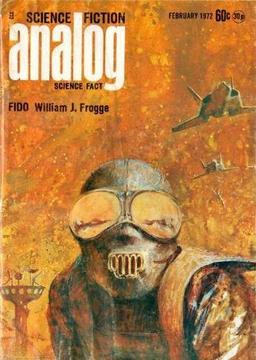

What I found interesting is that both issues featured lots of writers who didn’t do much in their careers, or who were strongly associated with Analog throughout. Each has a writer who published only the one story: Terrence MacKann and Ralph E. Hamil. Each has a novelette by a writer who ended up publishing very little (Glen Bever and David Lewis). There were actually quite a few single story writers in 1972 in Analog, even with cover stories (“Fido” by William Frogge in the February issue, left). But that was also happening in 1971, with writers like G. I. Morrison and John Paul Henry in addition to MacKann.

Of course this isn’t unheard of in other magazines, but the frequency at this time in Analog seems a bit high. I’d suggest that Campbell was really looking hard for new writers, partly because many of the veterans had left him behind; and that the reason some didn’t have long careers was that Campbell was by then a bit out of touch with where SF was going. (To be sure, he did have some “hits” – Jerry Pournelle, most obviously, also F. Paul Wilson, and Stephen Robinette, but we might also note that the first story Howard Waldrop ever sold appeared very early in Bova’s time, and may well have been bought by Campbell.) Well – that’s a thought, anyway. It may be that I’m just off base and the frequency of “one-shot” writers at the prozines was always thus.

Rich Horton’s last Retro-Review for us was the June and July 1960 issues of Amazing Science Fiction. See all of his BG reviews here.

Excellent article, John. I’m afraid my memory of these issues, this range of issues, is dim, while you recall quite a bit. I had all the issues Jan 1950-Dec 1970 and then bought sporadically after that, but I recognize these covers. I did read the Dickson, probably in paperback.

Thanks RK! But Rich wrote this one, not me. I can barely remember the stuff I read last week!

Sounds like you read Analog during some of its most vibrant years, though. I hear a lot of older readers say it lost steam in the late 50s and never recovered. John Boston, for example, claims 1958 was the last good year under Campbell:

https://www.blackgate.com/2015/03/13/an-astounding-science-fiction-testimonial/

And Barry N. Malzberg and Bill Pronzini felt the need to defend Astounding in their book The End of Summer: Science Fiction of the Fifties:

https://www.blackgate.com/2015/03/16/barry-n-malzberg-and-bill-pronzini-on-astounding-science-fiction-in-the-1950s/

What are your thoughts?

Thanks, RK! I only discovered Analog with the August 1974 issue, classic Bova-era stuff … but it’s a delight to read these earlier one, even in the enervated late-Campbell era.

Before long I’ll have a review of the other issue depicted here, the February 1972 issue, the last to feature only Campbell stories (though Bova wrote the editorial and was officially the editor) — that’s the one with William Frogge’s “Fido” on the cover.

Hi John,

Buzz Dixon was a regular in letters to the editors in the 70s. Most famously he ran a kind of running debate with Ted White in AMAZING over music, the military and homosexuality.

Cheers,

Kevin.

I remember Common Denominator – as a VERY involving story not needing much of a stretch of imagination.

I didn’t serve during Vietnam (I was 16 when Saigon fell), but I’ve known a LOT of vets from that timeframe, and the evil act was little IF ANY worse than the “fragging” that happened during that war.

I’ve also known people I could believe COULD pull such an action.

IMO a very underrated story, and arguably should have been a Hugo nominee if not winner.

I don’t think my review is much at variance with your comments — I do acknowledge, for example, that David Drake greatly liked the story and shared your opinion as to the plausibility of the bad guy’s action.

As for the Hugos — this was a spectacular year for novellas, and I don’t think I’d displace any of the ones on the ballot, except maybe the winner (Le Guin’s “The Word for World is Forest”). I think “The Fifth Head of Cerberus” is one of the great stories in SF history, and I also love the Pohl story (“The Gold at the Starbow’s End”), plus there’s another great Pohl story, “The Merchants of Venus”. But I wouldn’t argue that “Common Denominator” was plausibly in the conversation as a potential nominee. It’s kind of a shame that Lewis’ career didn’t last longer — as I said, he had real potential.