Writer’s Workshops: Under the Black Flag

I actually once said to a fellow writer, “The best thing you could do for art is cut off your hands and bury your typewriter.”

I actually once said to a fellow writer, “The best thing you could do for art is cut off your hands and bury your typewriter.”

Beyond the words themselves, it’s hard to know what’s worse about this: that I said it to someone I’m sure I liked or that I can’t remember to whom I said it.

I know it was at the Clarion Writer’s Workshop in the summer of 1985, then held at Michigan State University in East Lansing. I knew it was someone I liked, because I liked every one of my fellow workshoppers. As I got to know the 16 other participants, I felt these are my people!

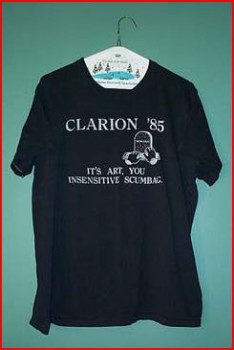

The context for the remark was a workshop session. For those unfamiliar with the format, everyone in the workshop delivers an oral critique of a manuscript handed out — and one hopes, read — in advance, then the author responds. Clarion workshops are machines for producing pithy one-liners — often put downs — the best (worst?) of which are memorialized on tee-shirts printed in the last week or two of the workshop.

So how was my comment received? With laughter, unbelievably. It was even graphically depicted in our year’s tee-shirt. (Image courtesy of Bill Shunn.)

I should say that my class was, according to our instructors, famously cohesive and collegial. Either they lied to make us feel good or other Clarion classes went at each other with lawn darts.

In any case, I can only imagine how hurtful my pronouncement was to the recipient and I’m ashamed of it to this day. If this essay were only about my own callousness and callowness (I was 27 at the time — I was, and remain, a late bloomer), that would be all there is to say. But I think there is something besides my own smallness of spirit at work here.

I’ve been a member of at least five or six weekly or monthly peer workshops in science fiction and fantasy writing since 1985, not counting assorted writer’s weekends over the years. There are some good things that come out of workshops, not least the camaraderie and a honing of craft. Workshops give you a shared critical lexicon, as well, a double-edged sword that I’ll return to anon.

The longer I participated in workshops, though, the more I came to feel that the most honest response I could make to a story was “it worked for me” or “it didn’t work for me.” I’ve come to believe that, barring obvious lapses of craft, we all make visceral snap judgments about other people’s work, then deliver post hoc rationalizations disguised as critiques.

Helen Garner, award-winning author of four novels and three short story collections, writing about literary prizes in The Australian said:

I have been a member of several judging panels. I have witnessed the strange dynamic of their functioning. Forces that outsiders can’t even conceive of are at work in those meeting rooms. Under all their beautiful intelligent reasoning, prize judges, like people in every sphere of action, are driven by unconscious urges. How could it be otherwise? They are not sphinxes, or oracles, or disembodied spirits. They are people, subject to moods, full of contradictions and unacknowledged emotions and thwarted longings of their own.

I think the same is largely true for workshops. Indeed, “how could it be otherwise?” If Clarion is the model for genre workshops, it is also the model for a pedantic and unhelpful focus on minutia and literalism (“as you know, Cyril, the boost phase of a Minuteman III is only 191 seconds…”) that often gives short shrift to character development and robust prose.

I think the same is largely true for workshops. Indeed, “how could it be otherwise?” If Clarion is the model for genre workshops, it is also the model for a pedantic and unhelpful focus on minutia and literalism (“as you know, Cyril, the boost phase of a Minuteman III is only 191 seconds…”) that often gives short shrift to character development and robust prose.

At their worst, peer critiques can be exercises in passive-aggressive one-upmanship in which the critic delivers a performance for his or her peers, rather than a helpful assessment of the work at hand. I’ve been on both sides of this dynamic: I honestly can’t say which is worse, but what made me finally bow out of my most recent workshop was the feeling that my critiques weren’t helping anyone.

The shared critical vocabulary (of which the Turkey City Lexicon is a good example) and the assumptions and attitudes that come bundled with it, are another pitfall of workshops, especially in the genre. To take one example, it’s good to know if you’re committing an infodump in your fiction, but not all exposition is an infodump. An intolerance for exposition that doesn’t advance the go-go-go plot of genre fiction can rob a story of depth and insight.

In a 1991 interview, Ellen Datlow, who’s edited more top magazines and anthologies than almost anyone in the field, said of workshops:

I keep getting mail from people who went to various workshops, but it’s mostly Clarion… and either they’re completely paralyzed and can’t write a thing for two years, or the kind of material that comes out of it seems very similar to each other… I find that they lose their voice… They don’t have any quirks to them. Like the writing is almost by the book; which makes perfect sense.

(Newer writers may have had a very different Clarion experience than I did, and it’s possible the downstream effects make for a better workshop environment in its spin-offs, as well. Revisiting the question recently, Datlow said the post-Clarion paralysis still exists for many graduates, but “the tonal similarities have diminished, happily.”)

Clarion lasts six weeks: long enough to boost participants’ critical abilities. But growth of the graduates’ creative chops can lag for years, in many cases, or never develop at all. And that’s not surprising — there isn’t a program in the world that can guarantee creative success. Meanwhile, the emphasis on criticism is a pain in the ass for everyone who isn’t interested in the workshopping game.

Clarion lasts six weeks: long enough to boost participants’ critical abilities. But growth of the graduates’ creative chops can lag for years, in many cases, or never develop at all. And that’s not surprising — there isn’t a program in the world that can guarantee creative success. Meanwhile, the emphasis on criticism is a pain in the ass for everyone who isn’t interested in the workshopping game.

I don’t think a great story is a story without mistakes; rather it’s a story that has something to say. You can’t workshop a bad story into a good story: you can help the author fix the obvious problems, but only the author can dream a piece of fiction’s compelling heart into existence, which is one reason why critiques often veer into rewriting a story. In my own experience, I did best when I didn’t try to “fix” stories that were panned in the workshop (assessments I almost always agreed with): but instead counted them as lessons learned toward the next story. Likewise, the best critiques I ever received reframed the story I was trying to tell, rather than focusing on mistakes, e.g., telling me I was building a house in a swamp, instead of criticizing the slipcovers on the furniture.

I know some very accomplished writers who regularly attend workshops, and other, equally accomplished writers who have foresworn workshopping except in the rarest of circumstances. Ask ten writers a question and you’ll get fifteen different opinions. Any piece of writing advice should get the Fortune Cookie treatment, but instead of appending “…between the sheets” at the end (amusing as that might be), the recipient should hear, “…at least that’s how it works for me. Under some circumstances. It will probably be different for you. Good luck!”

A very clear and honest assessment of workshops.

Interestingly, I see many parallels with your description of your experience of writing workshops, and their effects on you and various writers, with my experience of grad school and its effects on me and other grad students.

Indeed, some of the parallels are quite uncanny.

James, thanks for the kind words. I have heard as much (about graduate school–especially Ph.D. programs) from other survivors.

You write: “I don’t think a great story is a story without mistakes, rather it’s a story that has something to say. You can’t workshop a bad story into a good story: you can help the author fix the obvious problems, but only the author can dream a piece of fiction’s compelling heart into existence.”

Yes.

Workshops, in grad school and elsewhere, never talk about their two major underlying assumptions. The first is that writing can be taught. Fair enough. It can indeed be taught, up to a point.

The second assumption is that writers will benefit from a COLLABORATIVE approach to their work.

Sometimes, for some writers, with certain work, this is sometimes true.

And sometimes it isn’t.

Mark, first, I completely agree: writing can be taught, up to a point. Second, I’m not sure whether collaboration is the issue (or maybe it’s a separate issue). Reciting a long list of things that are “wrong” with a story isn’t really collaborative, though. It’s showboating at the author’s expense.

Robert – I need to be more clear. By collaborative, I mean there’s a buy-in on the part of participants that their story will now be worked on collectively, by a workshop leader(s) and by other members of the group. What began as a private enterprise is now open to the mind of the hive. For better or for worse.

And yes, it can also be a great opportunity for grandstanding.

Does that make more sense?

I’ve never attended a writers workshop, but I regularly participate in a weekly writers group. Like you, I found that one of the great things about critique sessions is how much I learn from other writer’s mistakes and successes. One of the discouraging things is how often people are “helping” by telling the critique recipient how they would write their story. The best feedback is based on helping other writers tell the story they want to tell.

Mark, I get what you’re saying.

Fritz, I think that tendency to rewrite the story by critiquers is partly born out of frustration, but yeah, distinctly unhelpful.

As always, it depends on the crowd. Your sample of 17 other writers is small enough that not unhelpful personalities may not be balanced out.

I share your concerns about over-pat critique technique; the Turkey City Lexicon bugged me for a long time before I ever reached a workshop. But again, it depends on the luck of the draw as to how many of your co-writers lean on its use.

I can only say that if I’d never gone to Clarion West, I would probably not have decided to put enough effort into what was a hobby to send anything out to a paying market.

If the workshop is not a perfect mechanism, it was certainly good enough for me.

Hutson, well, my sample isn’t just those 17: in 29 years I’ve probably workshopped with 100 different writers, including undergraduate and graduate fiction workshops. I agree that the culture of the workshop matters, but I do think there are structural problems inherent in the process.

That said, I loved Clarion, and I’m friends with many of my classmates and instructors to this day. It was a turning point in my life, and my life was enriched by it.

[…] Writer’s Workshops: Under the Black Flag […]

[…] My essay, “Writer’s Workshops: Under the Black Flag,” is live at Black Gate. […]