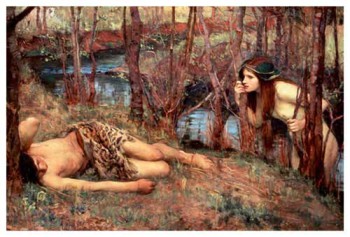

Ancient Worlds: Heracles and Hylas

As the Argonauts come closer to their destination, Apollonius finds himself with a problem that is familiar to many a DM: he has one character that significantly outclasses the other players. I refer, of course, to Heracles. A good adventure relies on tension and tension requires the possibility of real danger. A character that can Herc-smash every obstacle that stands in the party’s way is frustrating to both the writer and the audience.

In other scenarios, you can kill this guy off. But when your over-powered character is a well-known minor god with a well-established canon, you’re in a bit of a bind. So Apollonious does the next best thing and ushers Heracles off-stage by means of a side-quest. As mentioned before, Heracles is travelling on the Argo with Hylas, a boy who acts as his bow-carrier. At a stop for supplies, Hylas takes a jug and goes to fetch water. At the spring, his beauty attracts the attention of the nymphs, who seize him and pull him into their pool.

When Hylas fails to return, Heracles goes looking for him and, in the process, misses the boat. When the other Argonauts notice his absence, they accuse Jason of ditching Heracles on purpose and demand that they turn around to fetch him. This is when a sea god appears (yes, it is a literal deus ex machina) and informs them that Heracles has a destiny that does not include the quest for the Golden Fleece and that it is against the will of Zeus that they turn around.

Take THAT, character with suspiciously lucky dice.

It’s a straightforward story and one that does a lot of handwaving. But just under the surface lie many other issues, and the primary one I want to deal with today concerns the relationship between Heracles and Hylas.

Hylas has not come to be Heracles’s companion by chance. Heracles came upon Hylas’s father, Theiodamas, plowing a field. Heracles was hungry, so he slaughtered one of the oxen Theoidamas was using and began eating it. When Theiodamas objected, Heracles murdered him and took Hylas. Apollonius tells us that Heracles then loved him and nurtured him from early childhood.

We are meant to infer (and most ancient writers did) that the relationship between Heracles and Hylas was a sexual one. Apollonius is portraying them as a pederastic couple, but he is not doing so neutrally.

Pederasty, in incredibly broad and generalized terms, was the practice of an older, well-established man, probably in his thirties or older, taking a young boy, probably between the ages of nine and fourteen or so, as a protege and a sexual partner. This is a very difficult topic even for trained Classicists to discuss, because it is one that is so emotionally and morally loaded and so difficult to approach from a modern perspective.

On one hand, the age of the younger participant is distressing, and should be. Even without any other coercion, what we now consider to be meaningful consent is simply not possible between a full-grown man and a child. On the other hand, if we are going to regard this relationship with horror, we must also direct that same horror at the vast majority of marriages in, say, fifth century Athens, when “women” (in reality young girls) were married off at the same ages to husbands of equal seniority. We tend to think in terms of analogy, and while this is often useful, in the case of an institution such as this it can be deeply dangerous. Greek pederasty can not be neatly compared to modern pedophilia or sexual abuse. But on the opposite end of the spectrum, it also cannot be compared to modern, consensual relationships between adults.

But apart from these complicating factors, there is the nature of how Hylas came to be in Heracles’s care. That is, they are not lovers. Hylas is a possession, a kidnapped child stolen from a murdered father. And what’s more, Apollonius reminds us of that fact when he tells us about Hylas’s second abduction at the hand of the nymph. This reminder, coupled with the fact that the sea god tells Jason that Hylas has married the nymph, suggests that this was less an abduction than a rescue. It also suggests that perhaps the loss of Heracles is not much of a loss.

As we will see in the coming weeks, Apollonius is establishing Jason as a new kind of hero. This quest will depend on diplomacy and guile more than brawn, and Heracles does not fit into this new model. Moreover, the author is going to promote a more egalitarian view of romance (relatively speaking), and the relationship between Hylas and Heracles does not fit into that picture either.

Next time: Harpies, clashing rocks, boxing matches… I think this book’s mostly filler.

This also seems to have been cut from the Harryhausen film …

That guy, man.

I love the Hylas picture caption.

[…] Ancient Worlds: Heracles and Hylas […]