Weird of Oz Considers Postbuffyism

When discussing television series, especially genre shows (particularly horror, science fiction, and fantasy), my friends and I sometimes use a couple of adjectives that are pretty relevant and meaningful to us and may be of interest to readers of this blog: “pre-Buffy” and “post-Buffy.”

Most visitors to the Black Gate website will need no introduction to writer/director Joss Whedon and the “Whedonverse,” a term that encompasses all he has contributed to fantasy media over the past two decades in virtually every medium: television shows, comic books, webcasts, movies. Ranging from seminal shows like Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Angel, and Firefly to comic-book continuations of those series as well as runs on other properties like The X-Men; from the hip web series Dr. Horrible’s Sing-Along Blog to a cult horror film like Cabin in the Woods to the third-highest-grossing film of all time (2012’s The Avengers): trust me, you’ve seen his work.

In this week’s informal musing, I’ll focus in on his first television show, Buffy, which ran seven seasons from 1997-2003 — not to discuss the series per se, but to explain what I mean when I use it as a benchmark in describing a television show as being “post-Buffy.”

Pre-Buffy, each episode of a typical television show tended to be self-contained, that week’s conflict or dramatic development wrapped up in its half-hour or one-hour time slot. Characters remained fairly static, so each new episode was essentially a reset: another scenario for familiar characters to confront and resolve in their characteristically predictable ways.

Buffy may not have been the first show to feature dynamic characters who changed dramatically over time, nor the first to have storylines that crossed episodes and had long-term implications (I’ve heard Hill Street Blues cited as one early contender in that regard), but it has been perhaps the most influential, certainly for later genre shows. Influential enough that to describe a show as “post-Buffy” is a legitimate and meaningful designation.

Buffy may not have been the first show to feature dynamic characters who changed dramatically over time, nor the first to have storylines that crossed episodes and had long-term implications (I’ve heard Hill Street Blues cited as one early contender in that regard), but it has been perhaps the most influential, certainly for later genre shows. Influential enough that to describe a show as “post-Buffy” is a legitimate and meaningful designation.

While the “Scooby Gang” or the “Scoobies” (as Buffy and her friends came to call themselves) typically dealt with single-episode capers, there was also a season-long story arc involving a “big bad” (borrowing parlance from video games in which a player confronts a series of subservient monsters and challenges to reach and defeat the “big bad” monster of each level). This larger arc slowly developed over the course of a season, building tension that drew viewers on from week to week to see how this larger narrative would play out. It was a safe bet that the bogeyman-of-the-week would be handily vanquished, but the threat(s) posed by the larger challenge were not so clear-cut: Regular viewers knew that in the Buffyverse, nothing was safe.

Sorry, no comfort zone here to reassure fans that regardless of how much the characters might suffer, they would always come bouncing back. Characters died (the lead died twice — and although she returned in true superhero fashion, unlike her comic-book counterparts it was never a hit-the-reset-button, everything-back-to-normal kind of thing: there were always serious consequences). Main characters — popular characters — died and they were dead. Dead and gone. Characters developed scars, sometimes physical, often psychological and with far-reaching ramifications. Characters grew up in real time and changed. They went off to college, lost a parent to a brain aneurysm and a friend to lycanthropy, developed “happily-ever-after” romances only to end in bitter break-ups…

[A brief aside here: when I began watching the series for the first time a few years back on DVD, my wife watched it with me. She had already seen it, though, when it ran in syndication. And whenever a new romance blossomed between two characters, for instance their first kiss, my wife sitting on the couch next to me would simply make the same enigmatic statement: “That can’t end well.” She wouldn’t elaborate, no matter how much I pestered her for spoilers. “You’ve just got to watch and see,” she’d say with a cruel smirk. And no, romance in the Buffyverse never ends well. It just doesn’t. It usually ends in death or worse. There was certainly a sadomasochistic side to how Whedon and his team of show-writers treated their characters. Man. No other series ever made me cry like a baby so often.]

I sometimes half-expected Xander or Buffy or Willow to just throw up their hands and protest, “Who’s writing this? Lighten up on us a little, huh? Just a little happiness, ye cruel gods of popular entertainment!” How the writers always managed to make the show also funny-as-hell, with at least a few laughs in even the darkest episodes… well, that’s why Whedon is considered a genius. Make ‘em laugh, make ‘em cry, often within seconds. Make ‘em feel like they just got off a roller-coaster ride. Shaken, scared, giddy: “Again! Again!”

Even a season’s “big bad” was not usually the biggest bad, to make just one more observation about relationships in the Buffyverse. Shifting loyalties, dramatic break-ups and betrayals: this is why the series was sometimes pegged a “supernatural soap opera.” It’s quite accurate, and it was deliberate. Whedon and company were never so interested in the monsters as much as they were the monsters as metaphors for American high-school (and later, college) life. As Whedon put it, “High school as a horror movie” (Said. Interview 2005).

Even a season’s “big bad” was not usually the biggest bad, to make just one more observation about relationships in the Buffyverse. Shifting loyalties, dramatic break-ups and betrayals: this is why the series was sometimes pegged a “supernatural soap opera.” It’s quite accurate, and it was deliberate. Whedon and company were never so interested in the monsters as much as they were the monsters as metaphors for American high-school (and later, college) life. As Whedon put it, “High school as a horror movie” (Said. Interview 2005).

So in narrative terms, there were three levels going on in any given episode: the self-contained story (or “monster of the week”) of that episode, the “big bad” storyline of that season, and the gradually unfolding story of the Buffyverse, with plot threads that stretched across seasons. Characters changed dramatically and came into their own. Just for one example: is Willow even recognizable as the same character from season one (mousy computer nerd with an unrequited crush on Xander) to season seven (lesbian witch who is quite possibly one of the most powerful beings in the universe)? It is that larger tale of gradual transformation that kept a loyal audience following religiously, and that continues to make new converts (and, so notes a 2012 study in Slate, has made Buffy “the most studied pop culture work by academics, with more than 200 papers, essays, and books devoted to the series” [Wikipedia. Retrieved 3.3.2013]).

That third level of over-arching narrative — the gradual unfolding and world-building of the Buffy universe — caused the term “retconning” to come into standard parlance. Retroactive continuity describes what the writers would do to make sure all the plotlines stayed consistent. If something in an early episode seemed to contradict a new development later in the series, they would work in some retroactive detail that explained why it was not a contradiction after all, but rather a then-incomplete understanding or not-fully-developed picture on the part of the characters. The rules did not just change arbitrarily — or, well, yes they sometimes did to serve a particular story, but then some rationale had to be worked out to keep the continuity intact. (We all know what a demanding and detail-oriented lot we spec-fic fans can be.) Of course, this had long been going on in comic books — which are long-running serial stories, after all — and so it is notable that Whedon and other series writers came out of (or later went into) that storytelling medium.

This way of looking at a season or several seasons of a show as a broad canvas allowing the writers to develop a complex story over time — as opposed to the old paradigm of looking narrowly at each episode as a self-contained unit — freed up the writers, directors, and cast, affording them the liberty to really capitalize on the possibilities of the format. After all, compared to its multiplex cousin, which has roughly a two-hour limit to tell a story, television has one major advantage: time. It’s a big shift in perspective. Instead of looking at a season as twenty-two slots to fill, one takes the view “Wow, we have roughly seventeen hours to tell a grand story. And if we get five or seven seasons? We could go epic.”

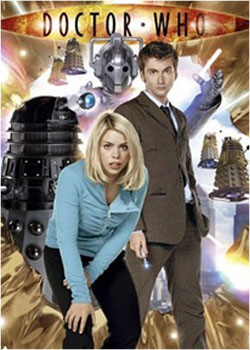

And that has arguably been the single biggest impact Buffy has made on the medium. This has been both direct, with show-writers going on to create or write for other popular shows like Lost, Smallville, and Once Upon a Time, as well as indirect, influencing shows like Supernatural, the new Battlestar Galactica (BSG), and the relaunched Doctor Who. Both BSG developer/head writer Ronald D. Moore and Doctor Who executive producer/head writer Russell T. Davies have acknowledged the influence of Buffy on the possibilities they saw with their own franchise relaunches. Personally, I consider BSG (2004-2009) and the Davies-helmed Doctor Who (2005-2010) to be two of the greatest television series yet produced, so this is a big pedigree. When one considers the influence of the aforementioned series on yet more shows, one can see that such lineage legitimately invests the term “post-Buffy” with real significance.

And that has arguably been the single biggest impact Buffy has made on the medium. This has been both direct, with show-writers going on to create or write for other popular shows like Lost, Smallville, and Once Upon a Time, as well as indirect, influencing shows like Supernatural, the new Battlestar Galactica (BSG), and the relaunched Doctor Who. Both BSG developer/head writer Ronald D. Moore and Doctor Who executive producer/head writer Russell T. Davies have acknowledged the influence of Buffy on the possibilities they saw with their own franchise relaunches. Personally, I consider BSG (2004-2009) and the Davies-helmed Doctor Who (2005-2010) to be two of the greatest television series yet produced, so this is a big pedigree. When one considers the influence of the aforementioned series on yet more shows, one can see that such lineage legitimately invests the term “post-Buffy” with real significance.

As Davies himself noted in an interview with Candace Moore (retrieved from Wikipedia 3.3.2013):

Buffy the Vampire Slayer showed the whole world, and an entire sprawling industry, that writing monsters and demons and end-of-the world is not hack-work, it can challenge the best. Joss Whedon raised the bar for every writer — not just genre/niche writers, but every single one of us.

I couldn’t have said it better myself.

And yet, Buffy itself was not the first SF/Fantasy show to attempt to create a consistent, multi-year story line. The epic series Babylon 5 started 3 years ealier, and was perhaps even more radical in its ambitions

J. Michael Straczyski’s Babylon 5 was intended from the very beginning to be a five year story, with a beginning, middle and end. JMS even claimed that he had an outline of every episode in his safe, waiting to be fleshed out. And while the term retcon may not have been used, he did this on several occasions to keep his story line intact (most notably in the episode Bayblon squared)

AS great as Whedon’s contributions have been, he clearly owes a debt to JMS. It would be interesting to see the two collaborate on a project, but one suspects there isn’t enough room in all their cinematic universes for that!

MisterBook: I was hoping someone would post a comment about Babylon 5. That show is on my “To Watch” list. Although I am not yet familiar with the show, I had heard that Straczynski had pre-plotted it to be, essentially, a five-year-long miniseries. So you’re absolutely right that it would have the distinction of being an earlier show that attempted “to create a consistent, multi-year story line.” I considered mentioning it in the post, but ultimately decided to see if it would come up in the comments discussion. And yes, so it did–very first one!

Homicide (1993-1999), Babylon-5 (1994-1998), Xena (1995-1999) — all very well established before Buffy. As well, it was Xena’s all musical episode that set off that trend for series to include one of their own.

I’m not trying to take anything from Buffy — but it is tiresome to see other, very influential series written out of the history. For example I have even see fans attempt to claim Buffy as the founder of David Simon’s The Wire. Hello? See Homicide ….

As well, occasionally characters and storylines in Homicide and Xena cross too: Homicide with Hill Street Blues, and Xena with Hercules.

C-Foxessa: Point well taken. As I mentioned in the post, Buffy was not necessarily the first TV series to develop the potential of the medium for long-term storytelling; that evolution was already afoot in the ’90s with the shows you cited.

That said, I think my main premise holds true; namely, Buffy has likely been the most influential show in this regard, making the adjective “post-Buffy” more widely applicable at least in genre television. For instance, I don’t think the producers of the new Battlestar Galactica or the new Doctor Who would’ve taken those shows where they did or pushed the bounds of narrative convention and character development so far had their only antecedents been Homicide or Babylon 5 or Xena. In that sense, I think Buffy is a benchmark — though certainly not the only show to consider when one opens up the discussion to a broader historical overview.

I’ve never watched a single episode of Buffy. But given how you’ve described it above, I don’t quite see why you think this show was such a benchmark. Everything you’ve talked about here seems familiar with other shows of the time (and earlier). The immediate one that comes to my mind isX-Files.

I agree with the commenters above; Buffy is not a gamechanger. To say so is to simply ignore that which came before in TV in SF and fantasy.

As someone who loves such shows, Buffy left me cold. It’s unimaginative, lacks vision, design, and good writing. The stunts are awkward and cheesy. Didn’t like the movie. It’s a one off idea: who would imagine a cute young girl hunts vampires and blah, blah, blah. An extended pun with a shelf life of about 4 min.

Loved “Serenity;” that in its own way was a bit of a gamechanger.

had their only antecedents been Homicide or Babylon 5 or Xena. In that sense, I think Buffy is a benchmark — though certainly not the only show to consider when one opens up the discussion to a broader historical overview.

It’s more likely that Whedon was influenced by those antecedents, because there was a cluster already established, already popular and receiving critical applause. Thus the green-lighters for network television green-lighted another drama series in that mode.

Those other arc series would have happened anyway, then, without Buffy, because those other series had already shown the way, were a cluster of success, and nothing gets repeated in entertainment more than what already is successful.

David Greenwalt — a writer on The Commish and X-Files which both pre-date Buffy — was an early writer in the Buffy saga. Since he is a co-creator of GRIMM, I often think “and?” given his past work.

I think it is wrong to give Whedon too much credit for the trends you are highlighting. One might even look episode to episode to find who worked on what. For example, the things I like about Firefly have more to do with Tim Minear’s influence than Whedon’s.

I’m a Whedon fan, but in TV there aren’t really auteurs. There are teams.

Doesn’t happen very often that my reply to a comment on my blog post grows into the equivalent of another blog post.

But I have to admit, I had to mull over the point raised about The X-Files. Ran it by my buddy Gabe, who helped me flesh out my thoughts and articulate a response.

You noted you’ve never seen Buffy, mcglothlin.13, but that doesn’t get me off the hook. The question you raise is valid: Aren’t the aspects of Whedon’s series that I most trumpeted just as applicable to The X-Files?

Without getting into the weeds of Buffy and distinctions between the two series, I can address your point by considering how well my argument regarding long-term narrative and layers of story fits The X-Files. Put another way, if we substituted The X-Files for Buffy in my premise, would my thesis still fit? And if it doesn’t fit, you must acquit.

Right off the bat I’ll acknowledge the impact of The X-Files and its hallowed place in genre television. And I’ll start by noting the most effective narrative improvement Chris Carter made over earlier shows that were the biggest influences on him. Carter always cites, first and foremost, Kolchak: The Night Stalker. Kolchak was a newspaper reporter who, in two-made-for-TV movies (The Night Stalker, 1971, and The Night Strangler, 1973), found himself uncovering evidence that the culprits behind serial killings in Chicago and Seattle are actually vampires. Those stand-alone mysteries spawned a television series (1974-1975), but the set-up soon strained all credibility. Not because of the supernatural elements, but because of the increasingly unlikely coincidence that this one beat reporter would always be uncovering some kind of monster behind every crime he happened to investigate. Coincidence that rivals the Die Hard movies or any long-running detective series where the protagonist works in some field wholly unrelated to homicide but just conveniently happens to find a murder has just occurred virtually everywhere he/she goes.

Carter wanted to do a “monster of the week” show with a premise that justified the protagonists uncovering monsters each week. Positing a somewhat independent, somewhat rogue FBI special agent who stakes out his own claim on all the bizarre, unsolved cases that get filed in the “X-Files” was an inspired move. Agent Mulder, with his skeptical partner Scully, has the resources and authority of the bureau at his disposal, and his own obsessions coupled with his superiors’ willingness to humor him and look the other way provide the perfect framework for his regular run-ins with the otherworldly.

And, yes, beyond the self-contained monster-of-the-week mystery of each episode there was an over-arching, unfolding narrative — what came to be known as The X-Files’ “Mytharc” with its government alien conspiracies and the recurring character of the Smoking Man. This larger narrative arc grew ever more complex and convoluted over the nine-year course of the series (to the extent that some viewers began to drop out even before Duchovny called it a day — Whatever the hell was going on with the aliens and secret impregnations is still not all that clear, even after two subsequent feature films).

But I would say that these two concurrent levels of narrative were still quantitatively less than what Whedon and company did with Buffy and Angel — the narrative threads of The X-Files were not quite as fully integrated. As Gabe put it, The X-Files almost felt like a hybrid — you tuned in from week to week and you were either going to get a stand-alone episode or you were going to get an alien-cover-up (or “Mytharc”) episode.

That said, its (not-always-seamlessly meshed) series-long narrative unquestionably distinguishes The X-Files as belonging alongside the shows other commentators here have noted (Babylon 5, Xena, Homicide — and I’ll add one more that happens to be one of my favorites: Twin Peaks) in driving the TV evolution of the ‘90s. To further push the evolution metaphor, one theory has it that new adaptations may occur in sudden leaps and even develop independently. Several TV shows began pushing the narrative possibilities of television during the ‘90s; this sudden cluster (as C-Foxessa describes it) may have just been the Zeitgeist, creating a fertile period of experimentation that would pave the way for a golden decade that saw The Sopranos, The Wire, Lost, Six Feet Under, BSG, and so many other landmark series that it’s hard to keep up with all of them.

I never said Buffy was the first. Why, then, did I single it out as a benchmark, as a paragon of these storytelling trends?

Obviously I am a fan of the series; others may be completely underwhelmed (or “left cold” by Buffy, as James May wrote). But love it or hate it, we are just viewers and reviewers. When it comes to the question of influence on other television producers, this can be objectively tested quite apart from my opinion or yours. And what I noted is that Ronald D. Moore (BSG) and Russell T. Davies (Doctor Who, Torchwood), arguably two of the most important names in sci-fi television of the last decade, have both singled out Buffy specifically as having a profound influence on their own work.

Although there has yet to be a comment posted here that agrees with me, I’m not an outlier in this opinion. Just a few minutes ago, I came across an article on the A.V. Club published only last year that contends Buffy “would become one of the most influential TV dramas of all time” and that “by the end of its seven seasons, Whedon and Buffy had reinvented the face of television.” Read the full article HERE.

By the way, ignore the 1992 Buffy film. Whedon had little to do with that. If you’ve never seen an episode of Buffy, and if you are thinking of checking it out, I envy you. You’re going to see “Hush” for the first time, and “Restless,” and “Once More, With Feeling,” and “The Body.” Oh, “The Body.” Let me quote Ian Shuttleworth on that: “Any sneerer of Buffy in particular or genre work should simply be sat down in front of a television and told to shut up for three-quarters of an hour while they are shown ‘The Body’; their awestruck silence afterwards may be taken as recantation or apology.” I heartily second that opinion.

Regardless of who’s responsible, it has been a welcome change in the vast television wasteland that good writing has finally found a home there – although I must confess, when one looks at the list of notable failures, shows that have died on the vine because the audience was not drawn into their mythologies and saw little hope that their mysteries would ever unravel (Threshold, anyone?), one does worry that this may not be a long lived trend!

However,just to point out another Buffy precursor that no one has mentioned, but which B-5’s JMS credited as one of his major inspirations, the late 70s BBC show Blake’s 7 featured some truly remarkable story telling, with a lead character making disastrous decisions long before Edward James Olmos, betrayals, deaths, radical plot changes and even the mysterious disappearance of Blake himself. We know Joss watched B7 (and some have pointed out its similarities to Firefly) – it would be interesting to know whether it influenced his work!

ChristianLindke: Indeed, as I noted, we can follow several celebrated writers who moved on from Buffy and Angel to other popular and important TV shows and films. Just to mention another: Drew Goddard, a regular writer with Whedon on Buffy and Angel as well as their recent co-scripted film Cabin in the Woods, has also been a regular collaborator with J.J. Abrams on everything from Alias, Lost, and Fringe to the movie Cloverfield. Thus, in tracing the lineal branches of members of Whedon’s scriptwriting team, we have a direct link to Abrams, the person who now helms both the Star Trek and Star Wars franchises.

“Regardless of who’s responsible, it has been a welcome change in the vast television wasteland that good writing has finally found a home there…”–MisterBook

Amen to that.

I’m not familiar with Blake’s 7, but it sounds intriguing.

[…] week’s post (“Weird of Oz Considers Postbuffyism“) was prompted by a term I used fleetingly in my review of the new Scooby-Doo series two […]

[…] Weird of Oz considers Postbuffyism […]