Mark Rigney Reviews The Holler

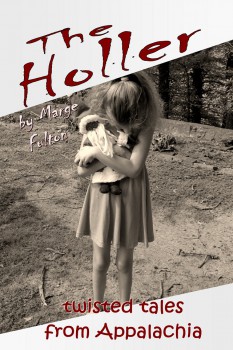

The Holler

The Holler

Marge Fulton

BlackWyrm Press (87pp, $11.95, 2010; kindle edition $2.99)

Reviewed by Mark Rigney

Brevity, observed Shakespeare in the ghost story known as Hamlet, is the soul of wit. Does it follow that it is also the soul of horror fiction? Writers as diverse as Shirley Jackson (“The Lottery”) and Jeffrey Ford (“The Night Whiskey”) rise at once to make the case for the sharp, jabbing effects of short-form terrors. Now enter Marge Fulton with The Holler: Tales of horror from Appalachia. Fulton’s arsenal starts with brevity in the extreme. The book’s eighty-seven pages pack twenty-four separate stories.

“Black Santa” opens the set with a deaf dreamer trying to regain the toy she lost as a child, getting it, and discovering that once you have Santa for a toy, the gifts just keep on giving. Hardly a horrific opener, except for the tawdry semi-Southern Gothic feel, and the next in line, “Preying Hands,” turns out to be science fiction (of the murderous fat camp variety). A haywire ATM spurts blood in “Blood Bank,” for reasons as yet undivulged, but we know this is Appalachia because leading lady Bree frequents the Boone Ridge Mini-Mart and the Nearly New Shop while, in another tale, a character slurps Mountain Dew.

Do these symbols necessarily denote Appalachia? Mountain Dew is just as easy to purchase (and slurp) in California as it is in Kentucky, and second-hand clothing shops positively litter non-Appalachian locales such as, for example, London, England. It is not that these can’t be trotted out, but their deployment feels surface, markers that beg for further specifics. At rock bottom, if the reader will pardon the pun, it is geology and hydrology that have set Appalachia’s boundaries, shaped its migration patterns, and directed its fate. Fulton does use natural signifiers on occasion, but her predilections are elsewhere, and besides, brevity has a way of excising closely observed detail. That is what makes short fiction so tricky.

For a work that comes billed and packaged as horror, Fulton shows a firmer hand with surrealistic fictions. “The Flock” is one of the collection’s strongest, a winged bellow of frustration aimed at the East Coasters who like to pretend they aren’t being serious when they refer to Appalachia (and the Midwest beyond) as “flyover states.”

Unfortunately, the collection’s closer showcases a slapdash approach to prose that is both prevalent in these pages and, frankly, distressing. “When My Ship Comes In” contains delightful flashes––what if delinquent teen aliens hijacked their daddy’s space ship and landed in a strip mine?––but it deracinates basic English mechanics. Consider, in a story told for three pages in consistent past tense, the following:

He would try to get them on at the call center, cleaning up the place. Kyle liked the way they eat. He put mini Moon Pies on his eyes and that cracks them up. They smush them into their heads.

And what to make of this paragraph, from “Black Santa?”:

The box was battered and the plastic shredded. That must be why he is marked down. This Santa looked robust. Lithely, she pushed the music button at the base. He began to sway and squirm, but no melody came with it.

Even aside from tense-switching oddments and a massive switch in authorial distance, it is questionable that Renzie, who is deaf, would notice one way or the other silence emanating from “it.” Now, true, deafness is a question of degree, but Fulton leads us to believe that Renzie is fully deaf with lines like “Her nights were always silent,” and Fulton does not write, above, that Renzie didn’t hear a melody––she states that “no melody came,” an authorial absolute. The question of who exactly observed that lack of melody becomes a puzzle worthy of Umberto Eco and his Six Walks In the Fictional Woods.

The bottom line: It is not unreasonable for readers to expect that an author blessed with a published collection (dare I say monograph) be conversant with essential strategies of story telling and prose-writing. A vivid imagination––which Fulton demonstrates in abundance––is not in and of itself sufficient. Craft matters.

__________

A slightly different version of this review originally appeared in Black Gate Magazine #15

Mark Rigney is the author of the play Acts of God (Playscripts, Inc., 2008) and the non-fiction book Deaf Side Story: Deaf Sharks, Hearing Jets and a Classic American Musical (Gallaudet University Press, 2003). His short fiction has been nominated for a Pushcart Prize and appears in The Best of the Bellevue Literary Review, Talebones, and Lady Churchill’s Rosebud Wristlet, among many others, and an upcoming trilogy is slated to begin in Black Gate in 2011. His website, with links to many of his original stories, stage plays and the dreaded Anti-Blog, is www.markrigney.net.