Some Thoughts on the Nature of a Serial

Serial storytelling is something of a mystery; even more so, perhaps, than most storytelling. When done right, it seems to hook an audience, to get them to invest heavily in the story being serialised. But for whatever reason, most serial forms have been pigeonholed as strictly popular arts; serial storytellers have generally been assumed to have a low amount of literary ambition. These presumptions about serials, and the way the form works, have always intrigued me — the more so since I’ve set out to write a serial prose fantasy of my own.

Serial storytelling is something of a mystery; even more so, perhaps, than most storytelling. When done right, it seems to hook an audience, to get them to invest heavily in the story being serialised. But for whatever reason, most serial forms have been pigeonholed as strictly popular arts; serial storytellers have generally been assumed to have a low amount of literary ambition. These presumptions about serials, and the way the form works, have always intrigued me — the more so since I’ve set out to write a serial prose fantasy of my own.

Let me try to define what I mean by ‘serial.’ The OED has “(of publication) appearing in successive parts published usually at regular intervals, periodical,” which is a start. More precisely, I’m talking about a narrative told across many installments, usually on a regular schedule, with each installment except the first and last expected by the audience to be incomplete, but usually containing some element of a genre or other story convention which will satisfy the audience.

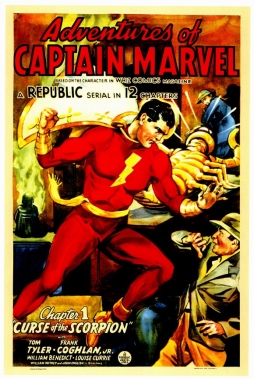

Every installment of The Adventures of Captain Marvel movie serial made sure at some point to have the titular super-hero in costume, using his powers, and usually also included fight scenes, detective work, plot twists, and exotic locales — because that was the sort of story it was, and that was what audiences were looking for. Individual chapters (or issues) of a serial may play about with these conventions — like an issue of the Steve Ditko Amazing Spider-Man, in which scripter Stan Lee apologised for not having the hero fight a villain in that particular issue, something unusual in the mid-60s. But go too far, too often, and you just end up telling a different kind of story — like, say, Scott McCloud’s Zot!, which started as a retro-adventure-hero story, and ended up becoming an examination of adventure fantasy and how it contrasts with realism.

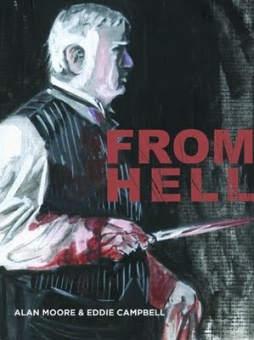

Sometimes, though, playing about with audience expectations actually becomes a part of what audiences expect from the individual chapter; they look for new things, new approaches to the story. And then sometimes the audience expects only the next part of an ongoing story, aware that it’s meant to be read as a unified whole; Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell would be an example. So serials are less constrained than they may appear to be.

Sometimes, though, playing about with audience expectations actually becomes a part of what audiences expect from the individual chapter; they look for new things, new approaches to the story. And then sometimes the audience expects only the next part of an ongoing story, aware that it’s meant to be read as a unified whole; Alan Moore and Eddie Campbell’s From Hell would be an example. So serials are less constrained than they may appear to be.

Like most literary definitions, a definition of ‘serial’ gets blurry around the edges. I don’t think a set of linked short stories, each of which is more-or-less complete in itself, could be said to be a serial. I wouldn’t call a series of novels a true serial, either, as even a novel in a series usually has some sense of completeness to it. I also typically think of a serial as something longer than a story continued over two or even three issues of a magazine.

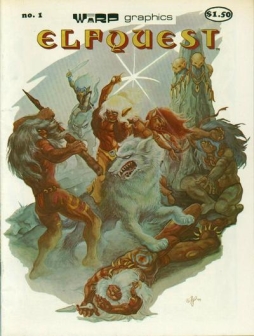

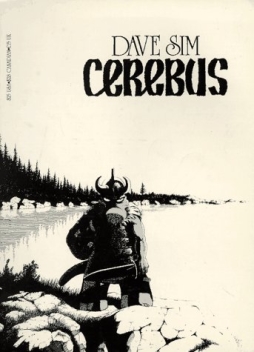

You can reasonably argue about whether traditional comic books count as a serial. A story told across six or eight or twelve issues certainly is; but does the entire run of, say, The Amazing Spider-Man count? Up until the last decade or two most stories were an issue or two in length, tied together by ongoing subplots. But even the subplots would be resolved at some point or another — for an anniversary issue, or when a writer left. In general, Spider-Man and similar characters are designed to have a beginning (or ‘origin’) unconnected with most of the stories told about them, and no ending whatever. On the other hand, titles like Elfquest — which originally was literally about, well, elves on a quest — are undoubtedly serials. There’s a beginning to the quest, and an eventual resolution. Dave Sim’s Cerebus, a 300-issue series about a talking barbarian aardvark, would be another example. So would Neil Gaiman’s Sandman, 75 issues plus a special or two.

You can read these things now as collected works (and Elfquest and all its sequels are in fact available free online), but they were originally published as serials, and designed to be read as such. Still, the way they told their stories varied considerably. Elfquest was fairly straight-ahead, with single-issue tales and multi-issue arcs that moved the overall story forward. Sandman was similar, but more baroque, moving back and forth in time, telling short stories and long stories and short stories linked together by various devices. Cerebus, on the other hand, paid more or less attention to its serial form at different times; there were points where the monthly book simply published the next twenty pages of the Cerebus story, regardless of whether it made any sense as an individual unit.

You can read these things now as collected works (and Elfquest and all its sequels are in fact available free online), but they were originally published as serials, and designed to be read as such. Still, the way they told their stories varied considerably. Elfquest was fairly straight-ahead, with single-issue tales and multi-issue arcs that moved the overall story forward. Sandman was similar, but more baroque, moving back and forth in time, telling short stories and long stories and short stories linked together by various devices. Cerebus, on the other hand, paid more or less attention to its serial form at different times; there were points where the monthly book simply published the next twenty pages of the Cerebus story, regardless of whether it made any sense as an individual unit.

This points up, I think, one of the potential drawbacks of the serial form. Usually, there’s a tension in a serial story between the structure of the individual unit and the structure of the overall design. An individual serial installment typically advances the overarching plot, but not necessarily by the most direct manner. It usually has a structure of its own, often resolving elements that were in play at the end of the last installment and then leading up to a cliffhanger ending of its own. When put together, and read as a whole, this repetition can seem overly mannered or simply forced. The plot may appear to amble from set-piece to set-piece rather than develop organically. As a whole, there’s a tendency to shapelessness in the serial form. How an individual creator deals with it is likely to depend on where they strike the balance between the installment and the story as a whole.

Particularly long serials have another set of pitfalls. If the story isn’t complete, but is being written as it goes along, it can take turns that in the long run will prove to be missteps. Even if the story’s been structured and planned-out ahead of time, the actual process of creation can suggest new possibilities, or force the story to take an unexpected form, which may not harmonise with the early installments. And, if the story’s long enough, the creator may not be same person at the end as at the beginning. Their style as a creator may have changed significantly; their attitudes as a human being may have shifted. Dave Sim and Cerebus are again a strong example here. His radical anti-feminism (Sim disputes the term misogyny, though many readers find the word appropriate) seems to have developed over the course of the book; his conversion to an idiosyncratic blend of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam certainly could not have been foreseen.

Particularly long serials have another set of pitfalls. If the story isn’t complete, but is being written as it goes along, it can take turns that in the long run will prove to be missteps. Even if the story’s been structured and planned-out ahead of time, the actual process of creation can suggest new possibilities, or force the story to take an unexpected form, which may not harmonise with the early installments. And, if the story’s long enough, the creator may not be same person at the end as at the beginning. Their style as a creator may have changed significantly; their attitudes as a human being may have shifted. Dave Sim and Cerebus are again a strong example here. His radical anti-feminism (Sim disputes the term misogyny, though many readers find the word appropriate) seems to have developed over the course of the book; his conversion to an idiosyncratic blend of Judaism, Christianity, and Islam certainly could not have been foreseen.

So there are practical artistic difficulties with serial stories. But, conversely, the attraction of serial fiction can be seen to go back at least to The Arabian Nights; Scheherezade kept her husband from killing her by telling stories which ended every night with “to be continued.” It’s a popular form. Dickens, one of the great populists in English literature, wrote best-selling serials, as did other writers like Thackeray and Trollope; but the form was around before them. Serials developed as a part of commercial publishing, in the late eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and evolved along with publishing. Penny dreadfuls and Boys’ Own stories became pulps which became comics. And the same with other popular media: Movie serials flourished. Soap operas started on the radio, and moved to TV. Which itself is increasingly turning into a medium dominated by prime-time serialised stories.

Wherever you find popular storytelling, it seems you find serials. You could probably argue that medieval mystery play cycles, which over the course of several days told the story of the Bible from creation to the final judgment, were an early kind of serial. From another perspective, you could plausibly argue that part of the popularity of team sports comes from a kind of serial storytelling structure; games make up a season, just as chapters make up a story, and individual players or teams have their own storylines, their own arcs, that initiated fans follow. But what, then, do all these things have in common? Why are serials so consistently popular?

This seems to me to be a deep question. I think it’s another way of asking something at the core of storytelling: why do people need stories? Why do people keep reading, or watching, or listening? What keeps them turning the pages?

This seems to me to be a deep question. I think it’s another way of asking something at the core of storytelling: why do people need stories? Why do people keep reading, or watching, or listening? What keeps them turning the pages?

People look for different things in a story. Some may look for technical mastery of the medium. Others may look for innovation, or the quality of imagination and ideas. A few will look for validation of their own world-views, or for characters who can be vehicles for their own aspirations. Still others will look for an indefinable quality of artistry, where all the elements of a work come together to create something beyond any individual aspect. But I suspect most people come to a story in order to lose themselves within it.

You could call this an escape, I suppose, but that means nothing unless one defines what is being escaped from and why. For my purposes at this moment, those questions are immaterial. What I mean to say is that I think there’s a desire to dwell within a story, to be wrapped up in it. It may be that this represents a sense of identification with a character; it may be that it represents a desire to encounter some new conception of the world; it may be that it represents a desire for the unity, meaning, and sense of structure inherent in a constructed narrative. I don’t know. I only know that it’s a desire that seems to exist, just as it seems to be natural for many people to construct their own experiences as stories; to find a narrative that makes sense of the world.

The serial story fulfills that desire in an exceptional way. You have the internal logic and structure of a story, but not the dissolution of a conclusion. The story goes on, before and after the particular installment. The serial nature of the story hooks the reader; it promises more to come.

In a 1994 interview in The Comics Journal, Neil Gaiman said:

[Gaiman:] One of the things that fascinates me about comics, one of the things that I think works against comics, genuinely works against it on a lot of levels, is one of the things that it also gets its power from: the serial nature of the medium. When I started out, when I first began writing, I didn’t realise that power. I figured that anything worthwhile that you did in comics had by definition to be short and self-contained like a book. Violent Cases or something a bit longer or Mr. Punch or whatever. One thing that I definitely learned over the years is that serial fiction has a level of depth and power and involvement for the readers that they don’t get from reading something all at the same time. I still think that’s one of the weaknesses of comics but I’m also now tending to think it’s one of its strengths … People can get involved. It’s something that fascinates me and something that I genuinely don’t understand.

[Interviewer Gary] Groth: But is that the kind of vitality comics need?

Gaiman: I don’t know. But it is a kind of vitality and it is something that works and something that you can tap into, something that as an artist and writer you can exploit; the action of living with characters for a number of years fascinates me. The fact that readers get to live with these characters for years and worry about them and think about them. I find it a fascinating phenomenon.

I think I’m fascinated by the same sort of thing. The way the serial form works its way into a reader’s life and stays there. I suspect that the story comes to seem like an aspect of one’s life; as your life unfolds, so does the story. It grows with you and changes with you. So the story becomes both a liberation and a reflection.

I’ve noted that serials have tended to be popular forms, and that there are several technical and practical challenges in the way of people trying to use them as a vehicle not only for story but also literary art. But you often see popular forms becoming a structure for highly-worked artistry. And certainly you can see people who have tried and are trying to make great work in the serial form, from Dickens to Alan Moore to David Lynch (I still rate Twin Peaks as the greatest TV show I’ve ever seen) to Jeff VanderMeer, who’s just started up a serial on his blog. People are writing serials in all sorts of venues, for all sorts of reasons. In fact, there’s a whole web serial community out there that I’m only just learning about.

I’ve noted that serials have tended to be popular forms, and that there are several technical and practical challenges in the way of people trying to use them as a vehicle not only for story but also literary art. But you often see popular forms becoming a structure for highly-worked artistry. And certainly you can see people who have tried and are trying to make great work in the serial form, from Dickens to Alan Moore to David Lynch (I still rate Twin Peaks as the greatest TV show I’ve ever seen) to Jeff VanderMeer, who’s just started up a serial on his blog. People are writing serials in all sorts of venues, for all sorts of reasons. In fact, there’s a whole web serial community out there that I’m only just learning about.

Personally, having seen what people have done with serials in the comics field alone is inspiring. I have a story in mind that I think works as a long serial, because of the way I want to use randomness to generate the matter of the tale. I think that I can tell the story in chapters that have a certain variety while still keeping to a certain overall feel. And I think I’ve got a structure of shifting points-of-view that will let me keep the story moving forward while also finding forms for the individual narratives of the individual chapters.

I want to write this story because I want to see how it ends. And I’m hoping that it will grow and change with me over the time it takes to tell it. But I’m also hoping that if I keep at the thing, eventually I’ll also come to understand how the serial form works. And how people relate to stories. And what it is that drives us to read.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Fascinating article, Matthew. The Gaiman quote in particular hit on something I’ve been thinking about myself for some time, in terms of how the most successful Black Gate stories – such as James Enge’s Morlock pieces, and Howard Andrew Jones’ tales of Dabir and Asim – have been serials.

And a nice shout out to two of my all-time favorite comics, CEREBUS and ZOT! 🙂

Yeah, comics have always been so powerful to me. I love Zot!, and for Cerebus … well, that’s complicated. The thing of it is, those early issues really are good — and by ‘early issues,’ I mean ‘at the very least the first fifty, really up through Church and State, and then maybe Jaka’s Story and Melmoth’ — which is 150 issues of the comic. And that’s a lot of comics. I think the second half of the storyline, leaving gender politics aside as much as possible, had a lot of failed experiments in it. But Sim was still trying to experiment, which is notable. So … I don’t know, in the end.

That Gaiman quote’s really stuck with me over the years. And the funny thing is, as far as I can tell, there still really hasn’t been much investigation of the power of serials and their relationship to an audience.

Great article Matthew! I’m enjoying your various analyses posted here on Blackgate. Your essays crystallize much that I have struggled to articulate to myself as well as others. Thank you.

Thank *you*, Kerstan!

One of the best literature courses I’ve ever heard about was a Dickens seminar that the professor insisted had to be a year long, not a semester, so that he could assign some of the novels as concurrent serials. The students had to swear to a pact not to read ahead, so they could experience those books in a way not too different from the way the original audience did.

This is the course that moved a friend of mine to change her major from Chemistry to English, to get a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature, and to devote her life to teaching. Whenever academia’s dysfunctions got her down, she thought again about that one class that changed her life.

Would those same books have had the same power, had they been assigned in great gulps, one novel per week? Probably not. My own experience with 19th century novels followed the conventional model, and every week’s reading was sort of like trying to chug a bottle of Bailey’s Irish Cream. (Okay, I’ve never actually tried doing that, but if I were ever crazy enough to, I bet it would be exactly as chokeworthy as trying to read Middlemarch in two sittings.)

Sarah: That is awesome. What a great idea for a course. And Dickens was somebody who really knew what he was doing with the serial form, too — Pater Ackroyd’s bio has some good bits on how intensely he worked on the structure of his stories, and how carefully he cultivated his audience.

(And I like George Eliot, but Middlemarch in two sittings? Yikes!)

[…] [Thanks to Matthew David Surridge for reprinting that quote in his Black Gate article "Some Thoughts on the Nature of a Serial."] […]