Worldbuilding Once and Future Fake News: Not Really A Review of Singer & Brooking’s LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media

What if I told you that the Sack of Limoges in Froissart… never happened?

Well, OK, you’d look at me blankly. After a moment you might ask, “I’ve never heard of Froissart. Where is that? French Canada?”

I’ve been reading LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media by Singer and Brooking. It describes the emerging world of Internet “news” where news passes from person-to-person on social media, no source is uncontroversially trustworthy, and where both information warriors and click-bait farmers are uninterested in the truth, except as a way of making untruths more plausible.

In this world, what determines a narrative’s success is not veracity but rather: Simplicity; Resonance; and Novelty.

Just switch the arena to “rumor” and this looks awfully like a greatly accelerated version of the pre-modern — especially Medieval and Renaissance — milieus we use as inspiration for Fantasy worldbuilding. Keep the rumor but return the tech, and it’s also a good jumping-off point for building a Space Opera future. Stay with me and I’ll explain. But first, back to the smoking ruins of Limoges.

The authors — Singer wrote a great book on robot warfare, by the way — talk about a US military training scenario that would make a good Traveller adventure: insurgents set up both a demonstration and an ambush, guaranteeing the former will get caught in the latter, the objective being to generate Internet images of an occupier-perpetrated massacre. The military response — as I recall; the index isn’t very good — is to contain or avoid the ambush. Singer and Brooking remark that this won’t do any good. The insurgents — if cynical enough — can just shoot the civilians anyway and blame the occupiers, or simply upload images from elsewhere.

And that’s what made me think of Froissart and Limoges.

Froissart is, of course, on my shelf. As every teenager (in my household) knows, Froissart was the famous chronicler of the Hundred Years War. And he describes the truly awful Sack of Limoges by the Black Prince.

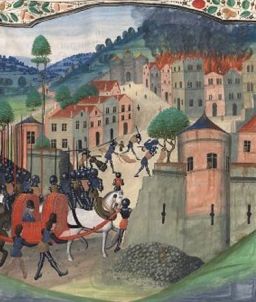

The Hundred Years War was a series of Late Medieval campaigns fought between England and France, at stake being the English crown lands in France, and then the crown of France itself. There were some notable battles, but mostly it devolved into the era’s standard mode of warfare: competitive peasant burning. According to Froissart, the low point came in 1370 when Prince Edward the Black Prince sacked the French town of Limoges:

It was a most melancholy business — for all ranks, ages and sexes cast themselves on their knees before the prince, begging for mercy; but he was so inflamed with passion and revenge that he listened to none, but all were put to the sword. Upwards of 3,000 men, women and children were put to death that day.

So much for chivalry!

Except, it’s been long known — I was told this back in the 90s — from another local source, that there were only 300 fatalities, pretty much the same number as the garrison. A few years ago, a letter from the Black Prince himself turned up, in which he boasted about taking 200 military prisoners. So, 300 garrison, minus 200 prisoners, makes 100 KIA. That leaves 200 deaths unaccounted for, presumably these are civilians — though that could be pretty blurry in a siege, especially because women probably routinely crewed the defences. So far from being a proto Nanjing, the fall of Limoges was business as normal. Tragic for the losers, but not Genghis Khan Was Here tragic.

Thus, the Sack of Limoges turns out to be Medieval fake news.

Let’s take a moment to savor that. I mean, Limoges isn’t on the edge of the Mappa Mundi. It’s bang in the middle of a literate, well-connected region, with taxes and trade and administration.

Just wow.

Why did Froissart lie?

He was more journalist than author, and more raconteur than journalist. He did the rounds of the courts of Europe reading from his book, gathering more stories, and — presumably — entertaining the courtiers with his conversation. Over time — or so I was taught 30 years ago — his allegiance shifted toward the French, possibly for purely commercial reasons.

To me this looks like the low-tech version of the information world described by LikeWar:

- Click Bait: “The Black Prince Stormed Limoges. What Happened Next Will Shock You…”

- Improved Truth: The sack comes at just the right place in the book. Fiction is more compelling than fact.

- Disinformation (“LikeWar”): The episode continues to make the English look bad, and the French into innocent victims.

- Filter Bubble: Froissart’s audience wanted to hear about how bad the English were.

And of course the story propagated then, as it does now, because it was simple (English massacre a town), resonant (right moment in the overall arc, plus women and children), and novel (but the Black Prince is supposed to be a paragon of chivalry!).

The only thing that’s missing is having the event staged for the benefit of the news sources, though political players did that do that kind of thing, for example Henry II’s discovery and reburying of King Arthur. Kings also, like certain modern governments, tried to control the narrative through monument building, censorship — for example, images of Elizabeth I were strictly controlled — and the equivalent of tweeting via proclamations and public entertainments:

“Scots Vow to Destroy the English Language!”

“You’ll Never Believe What The Templars Really Worship…”

“Turks Mistreat Our Pilgrims and the Kings of Christendom Do Nothing!”

Jump forward a couple of centuries into the 17th, we even have the equivalent of the Balkan click-bait factories. An article in Volume 1 of Fortean Studies describes the contents of broadsheets; everything from “Westmorland Wife Murderer Confronted By Angel”, through to “Terrible Earthquake Destroys Prague no Vienna no Hereford”. Presumably, before broadsheets, there were minstrels and story tellers. Hence Prester John, the Land of Plenty, and other curious myths of the Middle Ages.

It’s too easy for us moderns to imagine pre-modern news as comprising of real information plus false information. And in hindsight that’s true because we read selectively, at least considering Procopius’s gossip about Empress Theodora, for example, but not his stories about her demonic husband Justinian wandering around without a head. We read Beowulf as legend, and Gregory of Tours as History. However, it seems clear that pre-modern societies were like the modern Internet but worse; being awash with fake news, but without the corrective of a live broadcast or video from a plausible news service. To an intelligent contemporary, all news must have been falsehood unless proven otherwise. You’ll know the rebel leader is dead only once you’ve seen his head on a spike.

Lots of Fantasy worldbuilding stuff comes out of this.

First, it underpins many of the stock tropes borrowed from history. Political public “theatre” — coronations, executions, marriages, pledges — is necessary in order to establish your chosen narrative in the population. An execution that happens behind closed doors doesn’t really take, and you’ll be dealing with impostors for the next twenty years. Similarly, if you want to know the truth about anything that you can’t check yourself, you send a trusted friend, and the strength of your relationship with them is more important than their skill or experience. When a young prince commands an army, that’s a little bubble of certainty out in the world.

Second, fantastic events — actual intrusions of the magical or mythical — don’t stand out in this world. Any news they generate evolves to be simple, resonant and novel. So, take Smaug from The Hobbit. Everybody would have heard of him. However, this wouldn’t have been very useful.

“Forget Smaug, it’s gryphons you have to worry about. Let me sell you this anti-gryphon ointment.” (Novel.)

“He and his treasure are far away in Mordor. Let me sell you this mining concession instead.” (Simple).

“He’s pining for his lost mate. This love song will melt your heart.” (Resonant).

“He protects the people of Laketown in return for child sacrifices, and their merchants have come to steal our children; let’s kill and rob them.”(Resonant. Novel).

“Smaug is a creature of the Elves. Join us in our fight against them.” (Simple. Resonant.).

“Dragons, let me tell you about dragons. There are sea dragons and desert dragons and the King of the Dragons… Buy me a beer and I’ll tell you the tale.” (Novel).

“Smaug was long ago slain by the Mayor of Laketown — I’ve seen the statue commemorating the great deed.” (Resonant, Simple, Novel)

It follows that in a pre-modern setting, Fantasy stuff would be hard to locate, and rarely trigger any sort of government intervention. You know one of those rumors must point to the Wizard’s Tower. However, the local Duke really can’t be chasing off after every fable. Similarly there wouldn’t be whispered rumours of the Tomb of the Treasure Lord. There would be hundreds of different versions of the story, most wildly off in some way.

In other words, the difficulty wouldn’t be in learning about rumors, it would be in sifting through the overwhelming tide of rubbish.

It also follows that you could hide some pretty major supernatural occurrences in actual history, as long as they left no archaeology. Seriously, a dragon could gut Carlisle in 1400 and the event would vanish into the fairy tales and broadsheets. Even contemporary historians would write it off as a rumor started when the Scots burned the place.

Now, finally, flip over and think about a Space Opera storyverse of the sprawling I can’t believe it’s not Traveller variety. It’s like the pre-modern world in that travel is slow compared to the scale of the setting. It’s like our networked modern world, except that deepfakes will be really, really hard to tell from the real thing.

Imagine you are on a world called Redbrick and want to travel to the world Oldenoak. How do you find out what’s there?

I guess the Redbrick government have a site with travel information? They do, but there’s this other site saying that they are conspiring with the government of Oldenoak to trick travelers to go there, where they will be enslaved. Then there’s this blog about how good life is on Oldenoak. However, it does contain an awful lot of adverts for ticket agencies. Another site claims a secret war has been going on between the two systems, and has video footage to prove it. Another says the place is run by lizard aliens. And then there’s a trading advice site that recommends buying defoliating flanges and selling them at a profit on Oldenoak, where they are needed. I don’t even know which cargo sites are real and which are scams. Sure my ship’s library lists several reliable ones but that information is several years old.

What sources do you trust? A local broker who has a reputation to guard. A pilot you meet in a bar who – says — she regularly does the Oldenoak run. Probably. Even so, when you come out of hyperspace at the Oldenoak System, you don’t really know what you’re going to find. All that technology has cancelled itself out, and you might as well be Odysseus or Sinbad or Sir John Mandeville.

Which, from a storytelling or roleplaying point of view, is great.

Ultimately, LikeWar: The Weaponization of Social Media is useful for writers and gamers who worldbuild because, behind the specifics of time and place, it’s one of those wisdom books not so different from the works of Machiavelli. Old Nick talked about the flow of power. Singer and Brooking do the same for online news in a well-written and entertaining non-fiction romp, with proper citations at the back. The book is also important to geeks because the Internet is our tavern. Buy LikeWar to understand the weirdness that occasionally sweeps in and disrupts our carousing. If it makes you think twice about sharing angry Star Wars memes, that’ll be a win.

M Harold Page is the Scottish author of The Wreck of the Marissa (Book 1 of the Eternal Dome of the Unknowable Series), an old-school space adventure yarn about a retired mercenary-turned-archaeologist dealing with “local difficulties” as he pursues his quest across the galaxy. His other titles include Swords vs Tanks (Charles Stross: “Holy ****!”) and Storyteller Tools: Outline from vision to finished novel without losing the magic. (Ken MacLeod: “…very useful in getting from ideas etc to plot and story.” Hannu Rajaniemi: “…find myself to coming back to [this] book in the early stages.”)

[…] MORAL EQUIVALENT OF WAR. M. Harold Page expounds on internet culture in “Worldbuilding Once and Future Fake News: Not Really A Review of Singer & Brooking’s LikeWar… at Black […]