Dwarves, Dragons, Wizards and Elves: Thinking About the Standard Fantasy Setting

You know, for a genre that should be based entirely around the thing, Fantasy really is lacking in that lovely little commodity everyone calls imagination.

You know, for a genre that should be based entirely around the thing, Fantasy really is lacking in that lovely little commodity everyone calls imagination.

I’m serious; there are three-book series kicking around called Elves, Dwarves, and Orcs respectively. That’s pretty much the holy trinity of fantasy clichés right there. And all the book covers I’ve seen lately feature these grizzled, Batman-ish, waylander types, which is fine, because Batman kicks butt, when he starts cropping up everywhere he just gets annoying, with all his gritty, gravelly-voiced sadness.

Despite the fact that fantasy is a genre in which the writer can do literally anything, put their characters in whatever situation they damn well please, everyone seems way too content with dwarves, dragons, wizards, and elves. We could have quadruple amputees with tentacles for eyes who fight off the slavering hordes of hell by playing rock guitar solos with their earlobes, but nope, we’re happy with elves.

My point is that fantasy, and all the genres like it, give writers a medium through which they can explore every facet of the human imagination, test the very limits of what we, as human beings, can envision and relate to, what’s within our power to articulate. Fantasy challenges writers to make social commentary and philosophical statements within the most fantastic and diverse circumstances possible. Fantasy has the potential to take its readers to places they could never conceive of, on adventures that transcend comprehension; with this tool, fantasy could become the most beautiful, poetic, and diverse form of escapism we have.

It could be, if we didn’t focus so much on the elves, the dwarves, and the dragons, but we do, because we’re idiots.

Fantasy is a genre that has become bogged down with clichés and tropes, archetypes and expectations. Apparently, in order for a novel to qualify as fantasy, there has to be sword fights, magic has to be present, dragons have to turn up at some point, and it absolutely must be set in a pseudo-medieval, sort of European landscape.

A genre that, by its very nature, should have no restrictions, that should be free of limitations and impossible to define, has become one of the most rigid and easily distinguishable genres in our modern spectrum, and you don’t have to be a barely qualified British Internet blogger to know that this is one big, smelly, contradiction.

A genre that, by its very nature, should have no restrictions, that should be free of limitations and impossible to define, has become one of the most rigid and easily distinguishable genres in our modern spectrum, and you don’t have to be a barely qualified British Internet blogger to know that this is one big, smelly, contradiction.

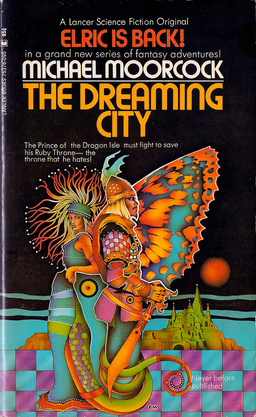

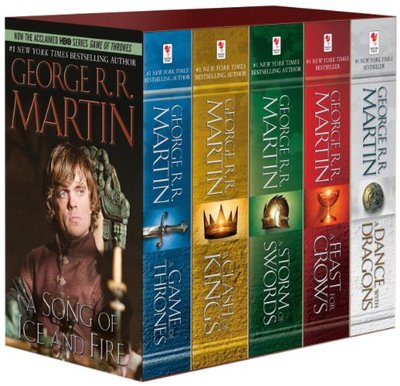

I’m pretty sure it’s gotten worse as of late, too. At least in the post-Tolkien era, there were some works that didn’t rely on The Lord of The Rings to do the heavy lifting for them, and in the 60s you had people like Michael Moorcock injecting a healthy dose of weird into the genre every so often, but today that’s not always the case. Think about it. Most of Joe Abercrombie’s stuff is just a few syllables away from historical fiction, and George R R Martin took the Wikipedia entry on the War of the Roses, added a morally ambiguous dwarf, and made a million billion dollars.

These works are still great, and I thoroughly enjoyed both A Game of Thrones and Heroes, but the brutality of the worlds they depict is almost hindered by our prejudices towards the period they take inspiration from. Most people that don’t live in hollowed out rocks know the medieval period was a nasty, brutal, and generally unpleasant time, so when they see folk wandering around on horseback, calling people ‘count’ or ‘lord,’ they get ready for some political intrigue, and they mentally prepare themselves for the oncoming cavalcade of incest; they’re less shocked by the sheer ruthlessness of the characters because, hey, that sort of thing happened back then.

What’s to prevent the story from being set in a small collection of tribes, in some poor indigenous region? Martin could still give us prejudice and discrimination, political intrigue, court spies, cloaked assassins, and morally ambiguous dwarves; he’d just have it in a different setting. It’d be a purely aesthetic change, it’d have very little effect on the overall narrative, but it’d defy expectations, take the reader to places they’d never thought about before, rather than another muddy medieval field, or some gloomy Gothic castle.

Don’t get me wrong, though — there are certainly a few writers out there that liked playing around with the fantastic.

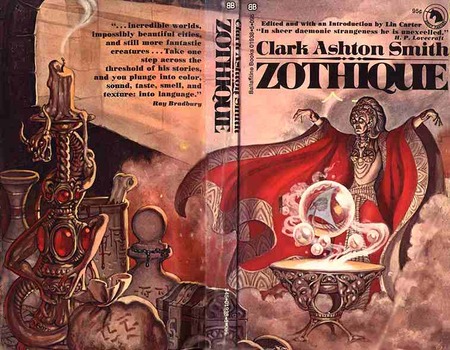

Reading a short story by Clark Ashton Smith is what I’d imagine taking a psychedelic drug to be like, all coruscating colors and shapeless alien things with complex societies and intricate cultures; entire walls made out of people’s faces; huge, singing flames that attract and burn unwary pilgrims; walking cities with giant laser cannons. It’s awesome, original, unflinchingly creative stuff. His worlds are colorful and inventive, wildly varied and unbearably beautiful, but still melancholy and morose in their own particular ways.

Reading a short story by Clark Ashton Smith is what I’d imagine taking a psychedelic drug to be like, all coruscating colors and shapeless alien things with complex societies and intricate cultures; entire walls made out of people’s faces; huge, singing flames that attract and burn unwary pilgrims; walking cities with giant laser cannons. It’s awesome, original, unflinchingly creative stuff. His worlds are colorful and inventive, wildly varied and unbearably beautiful, but still melancholy and morose in their own particular ways.

Or you’ve got Michael Moorcock, whose influences can be seen in Warhammer 40k, an entire generation of fantasy fiction and even the odd video game, like that Dark Souls thing I was talking about a little while ago.

Ask the big burly cockney about town, though, and they’ll either laugh at his name or hit you with a two by four (the cockney is a reclusive creature that feels threatened by anything that doesn’t involve punching or soccer.) Still, though, he once wrote about a demi-god harvesting copious amounts of blood in order to create a fortress.

That right there, that’s what I’m talking about. There’s probably a whole load of other authors still doing the same thing, authors I don’t know about because imagination is a quality so rarely celebrated in fiction as a whole; the worlds of these writers are fully realized, detailed, intricate and beautiful and, despite the strange beings that inhabit them, despite the odd circumstances they are placed in, these worlds never feel too far-fetched or alien because their creators pour so much love into the small details. They retain their mystery because the reader discovers these worlds alongside the narrator, rather than being told about them outright.

In The City and the Stars by Arthur C. Clarke, the reader learns about Diaspar and the history of Earth alongside Alvin and, in The Dark Eidolon by Clark Ashton Smith, the reader is just as surprised as everyone else when the devils and monsters and skeleton things leap out of nowhere and start playing music. Tolkien could probably learn a thing or two from this lot.

In The City and the Stars by Arthur C. Clarke, the reader learns about Diaspar and the history of Earth alongside Alvin and, in The Dark Eidolon by Clark Ashton Smith, the reader is just as surprised as everyone else when the devils and monsters and skeleton things leap out of nowhere and start playing music. Tolkien could probably learn a thing or two from this lot.

Heck, Tolkien set the stage for all this (you thought I wasn’t going to mention him, didn’t you?) by laying out such a clear and detailed world — and by selling so many bloody books — that he pretty much gave everyone else a free ride on the fantasy train. He laid down the basic rules of your typical fantasy setting: Dragons breathe fire, hobbits have hairy feet, wizards are old, elves shoot bows, dwarves have beards, and orcs like killing stuff. These are rules which have been around since the sixties, when The Lord of The Rings started getting popular; these are rules that haven’t budged an inch since.

Surely, though, there’s got to be a reason for the prevalence of this thing, there’s got to be a reason why George RR Martin, Joe Abercrombie, and all their derivatives soar to the top of the best seller lists and the likes of Michael Moorcock wallow in relative obscurity. Why The Times revels in the creative splendor of The Lord of the Rings, but probably hasn’t even heard of Clark Ashton Smith.

I think it’s simple, really. The creations of Tolkien are, at least on a basic level, easier to relate to. Tolkien’s elves, dwarves, and wizards might have seemed new and original to most people, but they were still human in nature: they still acted like people, spoke like people, had the same motivations as people and, except for the pointy ears and hairy feet, weren’t that much different from people.

In plenty of cases, Tolkien still used phrases that readers already knew: words like elf, dwarf, wizard, and dragon weren’t new terms or even new creations, really. He merely reinvented what those words meant. Elves, for example, went from being Santa’s chirpy little helpers to tree-hugging hippies and Orlando Bloom lookalikes. That’s inherently more approachable then Smith’s seven-syllable name for the residents of an alien planet with eight arms, twenty-two legs, and a complex social hierarchy centered around goat cheese.

No matter how well Smith developed his creation, there will always be potential readers who are going to be intimidated. That’s probably why The Lord of The Rings sold as well as it did, and why Clark Ashton Smith is on the verge of being forgotten.

No matter how well Smith developed his creation, there will always be potential readers who are going to be intimidated. That’s probably why The Lord of The Rings sold as well as it did, and why Clark Ashton Smith is on the verge of being forgotten.

The success of LotR is likely why Middle Earth-like settings are still so widely used, but you didn’t need to be told that. I think the reason behind the popularity of Tolkein-esque settings isn’t that every author and his dog is still trying to cash in on the success of an author who died in the seventies, though. I think it’s because Tolkien’s rules are now accepted ‘fact’, if you know what I mean. Everyone knows that elves shoot bows and live in forests; everyone knows that dwarves like mining, hitting things with axes and hate elves; and everyone knows that orcs are big, shouty green things. No explanation’s necessary, you can just jump straight into the sword fights.

When an author puts a gun to Tolkien’s head, nicks all his ideas and starts gobbing off about elves five minutes later, everyone knows what he’s on about, so the author doesn’t have to waste time on a big exposition dump that’ll probably turn most readers off; they can focus on character development, action, the narrative, all safe in the knowledge that the reader knows what’s what, aware that they don’t have to memorize an entire dictionary’s worth of useless and nerdy sounding new words. And that’s always good.

Attempt what, say, Michael Moorcock does, though, and describe a snarling pack of donkey buffalo men, and you’ve just confused some of your less imaginative and less adventurous readers. In fact, you’ve probably just made one or two of them cry.

Attempt what, say, Michael Moorcock does, though, and describe a snarling pack of donkey buffalo men, and you’ve just confused some of your less imaginative and less adventurous readers. In fact, you’ve probably just made one or two of them cry.

It’s because they have no point of reference. Most people have never seen a donkey buffalo man, so they have no real clue what they look like and all suspension of disbelief goes up in smoke. Say the word orc, though, and they’ve got those three really long movies they saw that one time, thirty odd years of post- Tolkien fiction, and a plethora of artwork, comics, and video games to draw inspiration from. It’s why works that experiment with setting and test our imaginations are still a niche in an increasingly mainstream genre.

So I can see why the well-established ground rules of the standard fantasy setting are attractive to some writers. They don’t scare off the mainstream reader, so more copies of the book get sold, and it allows you to focus on other stuff, like character development, or sword fighting, or motorbikes, or that one bum hair you have a particular fondness for, whatever.

The thing is, though, it won’t really sell more copies of the book, because everyone and their mum has had the same idea. And that book, complete with its gritty, Batman-ish protagonist, is just going to get lost in the crowd, because you can’t tell it apart from the generic fantasy novel sitting next to it. You can’t draw a picture of a protagonist’s fully formed and complex personality, after all.

The same sort of appeal lies in that medieval, vaguely European part of the fantasy setting as well; it’s one of those periods of history that everyone pictures more or less correctly: there are knights; the church is powerful; there were kings, barons, lords, and counts; there was political strife; and there were probably Vikings at some point. And Vikings are awesome. It’s one of those periods that, alongside the Greek period, is easily identified, heavily steeped in mythology, and poorly documented, so you can take some liberties with the truth if you really, really want to. Here, everyone knows what they’re supposed to be imagining and no one runs off crying to mummy.

I’ve a feeling that’s why the likes of Joe Abercrombie and George R.R. Martin (the formers, demons, dragons and zombies aside) so often neglect the orcs and wizards and just focus on writing about normal human beings with funny names. No monsters or magic, just normal people being nasty to each other.

I think there’s this perception that monsters and demons are all just a little bit childish, and that you can’t have a truly mature fantasy like the kind Joe Abercrombie and George R.R. Martin are going for without dropping them entirely. This is why so many mainstream authors forgo them altogether, all for the sake of this gritty, gravelly voiced attempt at ‘realism.’ Which makes absolutely no sense in a fantasy novel, but oh well.

I think there’s this perception that monsters and demons are all just a little bit childish, and that you can’t have a truly mature fantasy like the kind Joe Abercrombie and George R.R. Martin are going for without dropping them entirely. This is why so many mainstream authors forgo them altogether, all for the sake of this gritty, gravelly voiced attempt at ‘realism.’ Which makes absolutely no sense in a fantasy novel, but oh well.

Either way, though, it’s a stupid approach, because there’s no point in calling your book a fantasy if nothing fantastic happens, and anyone who’s read Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane tales knows that you don’t need to forget about demons and witches and castles and all that in order to be mature and atmospheric. Martin might make some light use of demons and dragons and some zombies here and there, but I think, for Game of Thrones, the appeal lies in the intricacies and nuances of the characters, the moral ambiguity, the intrigue, espionage and politics, as opposed to the dragons and big battles with devil-goats. That’s fine, that’s great in fact, it’s just that the slightly more fantasy parts of this fantasy aren’t central to its appeal, if that makes sense.

In the end, though, if you strip away all the sword fights and muscular characters, all the dragons and wizards and elves, all the thousands of years of crap that’s piled up since the genre’s inception, then what you’ve got left is imagination, complete and utter freedom to do whatever you want and go anywhere you want to go, whether it’s possible or not. Because, at the end of the day, fantasy and sci-fi are the only two genres that let you do that.

I’m not calling on the entire genre to suddenly change direction and become something entirely different; that wasn’t what this article was about. If I didn’t love fantasy as it is, I wouldn’t have written another of these posts discussing the thing. All I wanted to do was think about this trend that’s been central to the genre since its inception, take a look at why it happened, and make everyone appreciate truly imaginative fiction that little bit more. Because, hey, there’s more to fantasy then swords, axes, and morally ambiguous dwarves.

There is General Fantasy and there is Classic Fantasy. If you don’t like Classic Fantasy or Fantasy that is very low on magical elements that’s personal oppinion. But that’s no reason to call the people who write them as cash grabbing and the people who like them unimaginative.

If you would like to see some more fantastical books, that’s one thing. But basically calling the majority of General Fantasy, and especially the highly popular works as “not fantasy” is highly inappropriate.

Connor,

Kameron Hurley, Robert J Bennett, Jeff Vandermeer and many others, published just this year, refutes your thesis.

I’d also recommend Dave Duncan’s West of January. Duncan usually writes the more recognizable “medieval” style fantasies, but this one is far closer to something that Gene Wolfe might have come up with. Come to think of it, Duncan’s The Great Game trilogy, made up of Past Imperative, Present Tense, and Future Indefinite, is also a fine example of a well-stretched imagination.

There’s also most of Tim Powers’ stuff, especially Declare. Oh yeah, and Gene Wolfe.

I think that part of the difficulty isn’t just that people like to write what they like to write, but that readers like to read what they like to read. I wonder sometimes whether Moorcock, Zelazny and their ilk would have found it easy to be published today, which makes me wonder whether there’s stuff out there we’re just not seeing.

Why elves, dwarves and orcs in particular? I think it’s actually a combination of Terry Brooks (with the assistance of Lester Del Rey) and Gary Gygax moreso than Tolkien himself.

Not to suggest Connor’s opinions here are necessarily wrong, but I’ve been hearing pretty much the same arguments for at least 35 years, long before Abercrombie and Martin became known figures within the genre. Back in the day it was mostly gripes about Brooks, then slightly later about D&D’s novelizations.

In my opinion, it comes down to two factors: 1.) Familiarity and, 2.) Sales.

Good, bad, whatever, what gets noticed and what puts bread on the author’s table is what people read, not necessarily what people write. The dilemma between art and money has probably been going on since at least ancient Greece (and probably earlier) and isn’t likely to die away anytime soon.

@Martin

I wasn’t trying to suggest that Low-fantasy classical style and low fantasy is inherently less valuable then imaginative fantasy, I discussed their merits in the post itself. I Thoroughly enjoyed Joe Abercroimbe’s The Heroes, for example, I just didn’t feel that it had to definitely be a work of fantasy in order to maintain its merits. My intention was to discuss more imaginative fiction and look at why low fantasy and classic fantasy settings are so popular. So sorry, if that’s the impression you got; I’m the writer and that’s my fault, but at the very least it wasn’t what I was trying to suggest.:)

@princejvstin.

As I mentioned in the post, there’s probably a whole world of these authors writing this sort of stuff. My knowledge of the three authors is pretty limited (although Jeff Vandemeer is on my reading list), but I’d like to hear a little more of your point.

@Joe H

It wasn’t so much Elves, Dwarves and Orcs, more the fact that they seem to be at the centre of the whole standard fantasy setting thing, so they served as a neat little short hand. I think it could be argued that, since, Tolkien was the first to do this sort of thing and since The Lord of the Rings has been the quintessential fantasy novel(s) for so long now that, the setting could be attributed to him, and that’s what I was thinking. I do see what you mean though, and I cant deny that Terry Brooks and Gygax have had a serious impact. To be entirely honest, though, I never really considered Brook when writing the post, I’ve always considered him to be the original Tolkien rip-off, and since I’m not the biggest fan off Tolkien as it is, I’ve avoided his stuff like the plague. He might be much more then that, though.

@Ty Johnston

You make an interesting point, actually, and I think that its even more relevant now, too with fantasy and nerd culture as a whole becoming increasingly more profitable. I would argue though, that it takes a strong piece of art to change the face of the business side of things. If that makes sense. If everyone followed what was successful, the genre would never change. And it has, at least to a degree. Still though, that’s not really accounting for social, economic and cultural change.

@Violette Malan

I’ll have to slap those on the reading list, although I cant guarantee they’ll get read soon. Gene Wolfe’s stuff has been on there for god knows how long, and besides I’m a little bit skint.

I think what you said about writers writing what they like to write and readers reading what they like to read is, similar to Ty’s point, and reading your point, sort of made me think that the new piece of art I mentioned in response to Ty’s comment would struggle to find a following if no one’s willing to pick it up.

Personally, I think Moorcock and the like might struggle to get published today, at least with a big publisher. I do think they’d find cult followings though, but then, I’d argue that they’re still only cult authors today, anyway. High influential, highly successful cult authors, but cult authors.

Thanks for the comments, and for reading by the way! I’m always glad for that whether you liked it or not, but, then, that’s probably because I’m stupid and refuse to go away when people don’t want me around 🙂

Interesting though experiment — what if, instead of “translating” the races into Elves and Dwarves, Tolkien had stuck with Quendi and Khazad? If nothing else, I think it would’ve made it more difficult for his idiosyncratic versions of the races to become the generic standards.

Certainly a way to stimulate a potentially vigorous discussion. Similar discussion in my one circle of friends once got so heated that we almost stopped speaking to each other, until we realised we were all bring a bit childish. Funny how when one us passionate about anything, fantasy included each has their preferences and pet hates.

I went through a long period of avoiding the mainstream and still tend to despise the happy elf and grumpy dwarf cliché. I suppose each to his own, but for sure I tend to agree, writing for what most people are comfortable with = sells books tends to see, in my opinion, a lot if fantasy becoming somewhat homogeneous.

@Joe H oooooohhhh. That is pretty intresting, actually. I wouldn’t say it’d have a massive effect on the success of the book and the detail of the world would probably win people over, besides that though, the original two names would still come packaged with tolkiens crystal clear vision, so they’d still have all the advantages I described. The names do sound more alien then elf and dwarf, though, and don’t have the benefit of being common terms, so I coukd see that detracting from their effect somewhat, but not hugely. What do you think?

@Tiberius

Ha ha, yeah I tend not bring this sort of stuff up in person for fear of water torture. I do tend to enjoy, writing about it here, though, and I love these big, digital discussions. I’m glad to see your two cents, too, and though its certainly not genre wide I do agree that there’s a bit of homogeny in mainstream fantasy. Like in all these roguish, gravelly voiced batmen for protagonists I keep seeing on covers

Connor — Yes, I don’t think it would’ve necessarily had a massive effect on the success of the book (after all, who’d ever heard of a “Hobbit” beforehand?), but I think it would’ve made it harder (but ultimately more interesting) for the second- and third-generation folks — Gygax and Brooks et al. — because they would’ve at the very least had to come up with their own names for the races.

(To an extent, Moorcock was already doing this — I’d argue that the Eldren/Melniboneans/Vadragh/Ndadragh are at least partially modeled on Tolkien’s elves.)

True, but you could say that some people have been making up their own names for tolkiens creations for a while: I once played a video game called kingdoms of amalaur and, admittedly, it wasn’t very good, but there was a race of creatures that were exactly the same as tolkiens elves, but called themselves the fae or something.

As for Moorcock, I would agree, but I think he gave each of the races you mentiined a twist that differntiated them: the melnibonians were grim and dark, and the vadragh were haughty, arrogant and complacent. There is, of course, more then passing resemblence, though. 🙂

Great piece, Connor.

Part of my problem with using Tolkien-style non-humans is there’s are very specific reasons why elves and dwarves hate each other and orcs are evil. To replicate that (which too often the imitators do) they then have to imitate all of JRRT’s backstory as well. Even Terry Brooks wasn’t as slavish as a lot of contemporary fantasists are.

Glad you enjpyed it fletcher 🙂

Tbhats a good point too: didn’t the elves abandon the dwarves when smaug took the loneky mountain? Like I said I’m not the biggest fan of tolkien, so my knowledge is limited. I can see that adding to the homogeny, though, 6 billion books with the same backstory but slightly different stock characters isn’t exactly riveting 🙂

I think there is a reason why Tolkien has survived the test of time (for over 50 years), while C.A. Smith is utterly forgotten(and also Moorkock to a lesser extent). I completely refuse the hypothesis that elves, dwarves and dragons are less original than let’s say Morthylla or Thasaidon (Smith was using lamias, undead and vampires, nothing new under the sun). Even Poul Anderson was using dwarves, elves , dragons and trolls at the very same time “The Lord of the Rings” came out. He wrote two amazing books and, like Smith’s stories, they are utterly forgotten or nearly so. The difference between Tolkien and writers like Anderson on Smith does not reside in the supposed cliches (elves/dwarves/etc), but on a deeper level. It is too long a story to write here. For me, Tolkien, compared to Poul & C.A. wrote a story that one thousand, nay, one million times more people were able to relate to. And he managed to do this, without any “commercial” concern. It’s not his fault but his merit if even after 50 years, high fantasy is not really able to escape from his shadow. As somebody said before, it was Lester Del Rey, the genius that found the way to exploit commercially Tolkien formula. But if a novel is cheap, the fault is not of elves’ or of the dwarves’. You can still use these old (far older than Tolkien) mythical figures in an original way (Scott Bakker did something like this with his Nonmen, Sranc, Wracu and Bashrag). Sorry if the english is crayy, I’m a Native Italian

I meant to write crappy, not cravy!! ;P

[…] 16, 2014December 16, 2014 ~ Woelf Dietrich I found this article useful. It makes you think about how we view recurring characters in fantasy, the giant […]

[…] fantasy literature lacks in imagination. At least that is what this guy at Black Gate is lamenting; elves, orcs and medieval European settings being all that encompasses fantasy these days. Or, as […]

@MorgonMax

I can see where you’re coming from, actually, and I really like your interpretation, I would argue though that CA smith used more then just vampires and the undead and what not, just read some his more sci-fi ish sort of stories for that. I. Do agree that tolkiens tales were more relatable then some of the other works at the time, but I think his redefinition of elves and the like could be an aspect of his success.you’re english was great, by the way, fantastic, even, and the comment had fewer typos then any of mine, which tells me I really should go back and edit them. But then, I can’t be bothered 🙂

@woelf dietrech

Thanks for sharing! Its always good when someone wants to tell their friends about my stuff. Because friendship!

I have followed this thread with some interest, as it has chimed in with some recent reading. I have been reading Beagle’s “Secret History of Fantasy”, which includes an essay by David G Hartwell. In this essay and in Beagle’s own introduction, the blame for the formulaic nature of much modern fantasy is laid at the door of the publication of the “The Sword of Shannara” which ushered in a wave of Tolkien type tales. The point being made was that the fantasy peddled was familiar, safe and recognisable – so the public knows what it is getting. A win situation for publishers but not so much for readers. I am no fan of Tolkien but I am no fan of Clark Ashton Smith, either. Tolkien’s prose is rhetorical and overblown and I do not think his vision of a rural mediaeval society a particularly attractive one. Smith’s vision is far more outre but he wrapped it in a polysyllabic prose that strangles the story. He would have been a stronger author if he had used one ordinary word instead of seventeen obscure ones. But Connor is right in one sense, Smith’s world feels a lot more threatening and that, to me, is an essential element of fantasy. In a Tolkien type fantasy, we can toddle along against a bunch of low lifes, fight fifty shades of orc, face near extinction and win, before settling down for a nice cup of tea and a crumpet. The protagonists of a Smith story can face all kinds of monsters and not survive. Let’s face it, we do not read this kind of literature in order to enjoy dissections of character or problems with courtship. There’s plenty of literature that provides that enjoyment, it just ain’t fantasy. Good fantasy projects ideas and visions that slew our perceptions. It makes us see the real in a new or different way. A good example of this is John Collier’s story “Evening Primrose”, which concerns a young man who decides to live in a department store only to find that he is not alone. The story does not contain magic, is very quirky and not a little terrifying. I suppose you could call it a horror story rather than fantasy but I swear if you read this, you will not look at a department store in the same way. Writers who deliver this kind of fantasy include Mervyn Peake, Franz Kafka, Jorge Luis Borges, Angela Carter, Tommaso Landolfi – more cerebral, perhaps but much more satisfying.

Neil

@NeilH

from what you write it seems to me that some of the points made by Hartwell, weren’t too different from some of those I touched upon in the post, although I didn’t blame Brooks directly (like I said I tend to avoid his stuff like the plague, so I didn’t feel comfortable talking about him too much). I can see why you don’t like CA Smith’s prose, but I love it personally: I think its brimming with personality, I think it adds to the overall alien feel of his worlds and his plot lines, contributes slightly, to the surreal nature of his works. But he certainly isn’t for everyone. As for Tolkien, I don’t like him because his works move at a snails pace, his prose feels patronising, and I dislike the sort of fairy tale feel of his stuff. I prefer darker stuff. That’s not to say his objectively bad, just that I’m not a fan.

And I’ll get to Evening Primrose, and all those other authours after I get through Violette Malan’s suggestions, and all the other books people keep telling me to read. Maybe then I’ll seem like less of a Muppet 😛

Although I think you’ve got many good points about the genre as a whole, I’m perplexed to see you describe George R.R. Martin as having abandoned monsters and demons. From the prologue of the first novel in A Song of Ice and Fire, he gives us the White Walkers, who are plenty creepy and something far weirder than mere zombies. The second chapter gives us giant wolves, and the promise of giants. As the series unfolds, we have an order of priests of the farseeing Red God who seem to have sacrificed themselves, or one another, so that the promise of resurrection happens in the here and now — a theocracy of fire-animated zombies, disguised as ordinary humans to the eyes of most characters, but less and less disguised to the reader. If Daenerys Targaryen’s accursed and stillborn child is not a vision of magical monstrosity, I don’t know what would be. To say nothing of the dragons.

@Sarah Avery

Ok, you got me there, I was just plain wrong and, at the very least I should have made reference to the dragons and white walkers and what not (I’ll edit one in though, no worries) I would argue that Game of Thrones does fit into the sort of standard fantasy setting idea (the second, pseudo-mediveal, one that is, not the dwarves and elves and what not setting) and that the undead and dragons are still very much part and parcel for fantastic fiction (although Martin does twist the formula with them a little). I think it could be argued that the fantastic elements of Game of Thrones aren’t at the centre of what makes it so great.

Your comment has made me think about Game of Thrones differently, though. Really, it stands as something of an example: what should be done with the standard pseudo medieval setting when its used; with it’s focus on plot and character it makes the most of the trappings of its setting, whilst still creating its own identity and universe, just not in a manner that overwhelms the reader. So, thanks for that, I guess

Glad you enjoyed my other points, though 😀

I don’t have anything new to add to this discussion that wasn’t already brought up in your post or in the comments of others. I just wanted to say that I enjoyed the post and overall discussion.

Question though, are you familiar with Moorcock’s essay criticizing Tolkien? I think it’s called “Epic Pooh”? It’s been awhile since I read it, but, if I remember it correctly, it has some similarities with your essay.

@James McGlothin

Glad you enjoyed it 🙂 it was a heck of a lot of fun to write, but then these posts always are.

I am familiar with Moorcock’s ‘epic -pooh’ essay, and, if I remember rightly, I found myself agreeing with a lot of his points. I don’t recall too much, though. I generally tend to struggle through essays of that sort if it doesn’t have my sense of humour, so not all of it went in, and if some of my points are similar to Moorcocks I wouldn’t really know. Still though, Moorcock is one of my favourite writers (as you can probably tell) so I’ve no problem with being sort-of compared to him. It might help me grow a beard like his, you never know.

[…] folgende Essay erschien am 14. Dezember auf Black Gate und beschreibt recht anschaulich die Stärken und Schwächen gängiger, […]

[…] Connor Gormley, Black Gate: […]

[…] Nowadays, though, almost everything Tolkien has included has become de rigeur. Crack open any mammoth tome of fantasy and there’s a very good chance you’ll find maps, histories, family trees, etc. etc. That’s all there because of Tolkien, who showed just how valuable it can be to create a setting with the same attention an author normally reserved for his characters. That’s not to say other authors hadn’t done similar things (E.R. Eddison and Robert E. Howard come immediately to mind), but it was Tolkien whose works demonstrated the value of it in a way others hadn’t. While I’m not an indiscriminate lover of such an approach – not every fantasy story needs, let alone deserves, this level of attention – I do think a good thing that writers of fantasy spend time giving some thought to the worlds in which their stories take place. Here’s hoping more of them don’t feel the need to keep trodding the same ground as J.R.R. Tolkien. […]

[…] the trappings of derivative, traditional high fantasy. Now, some time ago there was a very involved discussion here that took umbrage against these clichéd fantasy tropes. While I don’t agree with all that […]

[…] I wrote a stonking great think piece thing about the Standard Fantasy Setting a while back and a lot of people read it. Some of those people liked it and some of those people […]

[…] fantasy literature lacks in imagination. At least that is what this guy at Black Gate is lamenting; elves, orcs and medieval European settings being all that encompasses fantasy these days. Or, as […]

[…] Connor Gormley, Black Gate: […]