Astounding Science Fiction, February and March 1953: A Retro-Review

I thought it might be worthwhile to take a look at John Campbell’s Astounding, from the early ’50s, after its dominance of the market had been shaken by Galaxy and F&SF. So here are two 1953 issues.

I thought it might be worthwhile to take a look at John Campbell’s Astounding, from the early ’50s, after its dominance of the market had been shaken by Galaxy and F&SF. So here are two 1953 issues.

I bought these two issues because the March issue has John Brunner’s first story for a major market, “Thou Good and Faithful.” I noticed that that issue also has the second part of a Piper serial that I hadn’t read, so I bought the February issue to get part 1.

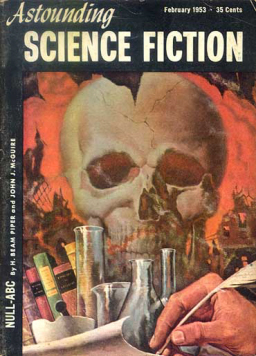

Details, then. The February cover, for H. Beam Piper and John J. McGuire’s serial “Null-ABC,” is by H. R. Van Dongen, a pretty good one with a skull on a reddish background (flames and smoke, I think), and books and test tubes in the foreground.

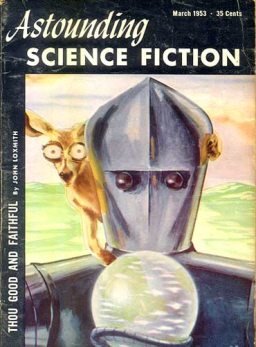

The March cover, for “Thou Good and Faithful,” is less to my taste. It’s by G. Pawelka, an artist with whom I am unfamiliar, and it features a robot with a monkey-like creature on his shoulder, holding a globe of sorts — a very accurate depiction of a scene from the story, but not a picture I fancy much.

The features in each issue are the usual: Campbell’s editorial (“Redundance,” about information theory, in February; and “Unsane Behavior,” about war and the naivete of both those who think it works very well, and those who think stories of Atomic Doom will prevent it, in March); In Times to Come, The Analytical Laboratory, Brass Tacks, and P. Schuyler Miller’s review column.

In February Miller considers a letter from a French reader about French SF, and an article by August Derleth about the state of SF; and he reviews Kurt Vonnegut’s Player Piano (positively), Groff Conklin’s Invaders of Earth (positively but not ecstatically), and a popular science book called Design for a Brain, by W. Ross Ashby, apparently about how animal brains work (rather than about AI, which is what the title made me think of).

In March he reviews a couple of popular science books about space travel, Hal Goodwin’s The Real Book About Space Travel and Chesley Bonestell’s Across the Space Frontier. Also, Donald Day’s first Index, Five Science Fiction Novels, ed. by Martin Greenberg (Miller did not like this anthology much), Green Fire by John Taine, and Gunner Cade by Cyril Judd (i.e. Kornbluth and Merril).

In March he reviews a couple of popular science books about space travel, Hal Goodwin’s The Real Book About Space Travel and Chesley Bonestell’s Across the Space Frontier. Also, Donald Day’s first Index, Five Science Fiction Novels, ed. by Martin Greenberg (Miller did not like this anthology much), Green Fire by John Taine, and Gunner Cade by Cyril Judd (i.e. Kornbluth and Merril).

In each issue the Science Article is by Wallace West, who was also a fairly prolific writer of fiction in those days — now all but forgotten, seems to me. In February there is “Oil, Secret Agents, and Woolly Bears”, about the complexities of oil refining. In March there is “Five Billion Dollar Magpie”, about the recycling industry of all things — I thought it a prescient article for 1953.

The two part serial, “Null-ABC”, by H. Beam Piper and John J. McGuire, is about 36,000 words long. It was later published — possibly expanded — as a novel called Crisis in 2140. It reminded me of nothing so much as a much later collaborative novel that was serialized in Astounding’s successor, Analog: Higher Education, by Charles Sheffield and Jerry Pournelle. The similarities are in the view of contemporary education, not in any plot resemblance.

In “Null-ABC” people have become suspicious of scientific inquiry, and even of literacy. A small group of Literates have become a closed guild. Chester Pelton is a department store owner who is running for Senator on the platform of “socialized literacy” — he wants the Literates to be forced to become servants of the government, supplying their services to all for free. It seems he is likely to win. But what he doesn’t know is that both of his children — a teenaged boy and a young woman — are closet literates. They have been taught in secret by the local schoolmaster, who is also the woman’s lover. Pelton also doesn’t know that much of his support comes from a faction of Literates who believe that if he wins they will eventually take over the government. The good guys among this faction want to push for a return to universal literacy. The bad guys just want power. And the other bad guys want to retain the status quo.

The whole thing is a bit (realistically) confusing. Anyway, the main plot revolves around a couple of sometimes conflicting schemes — one, to discredit Pelton by revealing that his daughter can read, and two, to frustrate Pelton by fomenting a riot in his department store. So, most of the action is focussed on the (rather silly, in many ways) battle for the store. It’s kind of a silly story overall, though I was caught up in it — it’s at least a decent read.

There are two novelettes in the February issue. Richard de Mille’s “Safety Valve” (9,500 words) posits a society which is very peaceful except for three days a year: the Lawless Days. A man from another country enters during those days, trying to deliver a message to the Mayor. Instead he is framed for the Mayor’s murder — until a mild twist saves him. I admit to not really getting the point.

Alan E. Nourse’s “Nightmare Brother” (9,300 words) is about a man subjected to tortures — simulated via electrodes in his brain. It seems he must be able to resist any level of torture to survive in deep space. I wasn’t convinced.

There is one well known short story in February: Walter M. Miller’s “Crucifixus Etiam” (7,200 words). A poor man from Peru goes to Mars in hopes of working out his 5-year hitch and coming home with enough to live on the rest of his life. What he doesn’t realize is that after 5 years on Mars he won’t be able to come back to Earth healthy. He also doesn’t realize why they are there — the story is, mining for tritium, but that doesn’t make sense. It turns out that they are working on an 800 year terraforming project — and that he and his fellows are making a noble sacrifice for people tens of generations in the future. Pretty effective.

Irving E. Cox’s “For the Glory of Agon” (7,000 words) is an interesting story to see Campbell publish. A warlike people from Alpha Centauri come to the Solar System. The people of Venus, Earth, and Mars have developed a workable triune society and have eliminated war. How will they resist the extrasolar aliens? A young human firebrand urges a move towards a desperate war effort, but wiser heads counsel, purely and simply, surrender. You see, the Agonians will be inevitably seduced by the happy and prosperous and peaceful Sol-based way of life (with the help of the “Rationalizer”) — to maintain a war-footing is to doom their people to constant unproductive work. Not bad.

The other February story is another peace of space boosterism, “The Cog” by Charles E. Fritch, Jr. (1,100 words) — a middle-aged man looks on as a spaceship gets ready to depart. He regrets his life decisions — a career in the law — and wishes he could be the merest “cog” in a spaceship crew. But he also realizes that all of society is necessary cogs in supporting space exploration. The final twist comes right at the end, nailing home the point.

The other February story is another peace of space boosterism, “The Cog” by Charles E. Fritch, Jr. (1,100 words) — a middle-aged man looks on as a spaceship gets ready to depart. He regrets his life decisions — a career in the law — and wishes he could be the merest “cog” in a spaceship crew. But he also realizes that all of society is necessary cogs in supporting space exploration. The final twist comes right at the end, nailing home the point.

The lead novelette in March is “Thou Good and Faithful” by “John Loxsmith.” “John Loxsmith” of course is a pseudonym for John Brunner. I have no idea why he chose that pseudonym, which he never used again. Most of his stories at that time were as by K. Houston Brunner or Kilian Houston Brunner. His most common later pseudonym was “Keith Woodcott.”

“Thou Good and Faithful” is about 17,000 words long, though he later revised and expanded it for his 1965 story collection Now Then! (wherein it was 19,000 words — thus it was first a long novelette, then a short novella — oh the bibliographer’s headache!). I’ve read the longer version and skimmed through the original. It’s a fairly typical Brunner revision (much like he treated many of his novels): an organic expansion throughout, revisiting word choices, adding fillips of description, but not adding any new scenes.

The story concerns an exploring ship in a crowded galaxy that comes to a potentially perfect world. Beautiful climate, and no intelligent natives. But some robots are discovered — who made them? Over time, the mystery is solved (well, not so much solved as the robots eventually just tell them what’s up). The story is overlong — it probably should have been about 10,000 words. It does have a fairly interesting theme concerning the ultimate destiny of intelligence — and a fairly non-Campbellian theme. (As with the Irving Cox story from February — certainly through the mid-50s at least Campbell remained happy to publish stories he found interesting that were not typically Campbellian in message.)

The other novelette is “Button, Button” by Thomas Wilson (14,000 words). An alien comes to Earth, to a Pacific Island where the Americans are developing a new bomb. The alien can mimic a human perfectly, and also exercise mild telepathic control. He is charged with deciding if humans are ready to be contacted openly. Some humans have figured out that aliens have landed, and they send an investigator. The story revolves around the alien’s flight, and his attempt to buy time to make his decision — which ultimately is to try to suppress the hydrogen bomb and give humanity a few more decades to solve their problems. Or something like that — I was a bit confused, and unconvinced by much of the blathering.

The other novelette is “Button, Button” by Thomas Wilson (14,000 words). An alien comes to Earth, to a Pacific Island where the Americans are developing a new bomb. The alien can mimic a human perfectly, and also exercise mild telepathic control. He is charged with deciding if humans are ready to be contacted openly. Some humans have figured out that aliens have landed, and they send an investigator. The story revolves around the alien’s flight, and his attempt to buy time to make his decision — which ultimately is to try to suppress the hydrogen bomb and give humanity a few more decades to solve their problems. Or something like that — I was a bit confused, and unconvinced by much of the blathering.

The only short story is Robert Sheckley’s “Fool’s Mate” (4,800 words), in which two equally matched space fleets confront each other. It seems their computers have determined that the alien fleet has a tiny positional advantage which nearly guarantees victory — but that neither fleet can attack since the act of attacking will ruin their position and guarantee failure. The standoff is psychologically devastating, until a man comes up with an idea — use one of the gunnery officers who has been driven insane to control attack strategy. You see, the other side’s computer will never be able to figure out a madman … Cute, I suppose, but not terribly believable.

The obscure writers always interest me. Only two of the writers in theses issue are really unknown to me, and both contributed stories of the somewhat naive and idea-centered type that I think Campbell liked to buy. These are Richard de Mille and Thomas Wilson. Richard de Mille published a total of six stories, two as by “Arthur Coster”, between 1953 and 1959. His other stories were in Fantastic, Science Fiction Stories, Authentic, Science Fantasy and New Worlds. Thomas Wilson published four stories: three in ASF (“The Face of the Enemy” (Aug 1952) and “The Entrepreneur” (Sep 1952) are the others), plus “Devil’s Cargo” in the March 1952 Future. There is also a story credited to “Tom Wilson”, “Local Custom” in the Spring 1954 Fantastic Story Magazine — could easily be the same guy.

Rich Horton’s last retro-review for us was the November 1958 and May 1960 issues of The Original Science Fiction Stories. See all of Rich’s retro-reviews here.

Surely you noticed the silly Astounding-in-joke reference to “World of Null-A”, by Campbell discovery and reactionary protege A.E.Van Vogt.

You know what, I certainly noticed that “Null-ABC” echoed “The World of Null-A” but it didn’t occur to me that it was in a sense a jape … but on thinking about it, I think you’re right … Piper and McGuire (and perhaps Campbell too) were making (somewhat gentle) fun of Van Vogt with that title.

[…] Horton’s last retro-review for us was the February and March 1953 issues of Astounding Science Fiction. See all of Rich’s retro-reviews […]

[…] Horton’s last retro-review for us was the February and March 1953 issues of Astounding Science Fiction. See all of Rich’s retro-reviews […]