You Can’t Read the Same Comic Twice: Justice League of America 183-185

I was planning to start the series of posts on Romanticism and fantasy this week, but something came up in the last few days that I’d like to write about; particularly since it seems to resonate with a recent experience of John O’Neill’s. Earlier this week, my friend Claude Lalumiére sold off much of his library of sf, fantasy, and comics in preparation for an upcoming move. I’ve known Claude for a long while, and esteem his tastes highly. It’s not surprising I came away from his sale with a huge amount of material. What was surprising, to me at least, was that of all the many things I picked up — fiction by Zelazny, Lafferty, Delaney, Tanith Lee; comics by Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Jack Kirby — the first items I chose to read were three Justice League comics from over thirty years ago.

I was planning to start the series of posts on Romanticism and fantasy this week, but something came up in the last few days that I’d like to write about; particularly since it seems to resonate with a recent experience of John O’Neill’s. Earlier this week, my friend Claude Lalumiére sold off much of his library of sf, fantasy, and comics in preparation for an upcoming move. I’ve known Claude for a long while, and esteem his tastes highly. It’s not surprising I came away from his sale with a huge amount of material. What was surprising, to me at least, was that of all the many things I picked up — fiction by Zelazny, Lafferty, Delaney, Tanith Lee; comics by Alan Moore, Grant Morrison, Jack Kirby — the first items I chose to read were three Justice League comics from over thirty years ago.

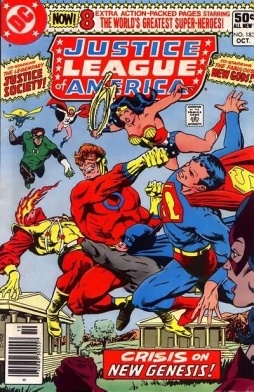

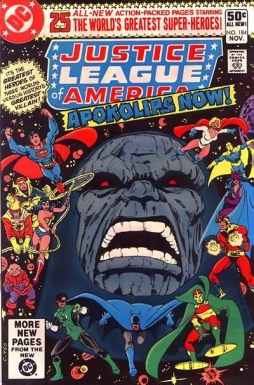

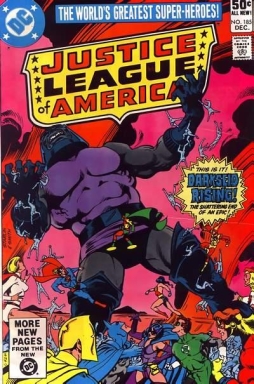

There’s nothing particularly exceptional about the books. They do feature the last issue drawn by former JLA mainstay artist Dick Dillin before his death, and the first two issues drawn by George Pérez, as well as dynamic covers by Jim Starlin. But that’s not why I was drawn to them. They’re a three-issue story, telling a tale of one of the JLA’s annual meetings with the parallel-earth Justice Society of America; that’s not why either. It’s a storyline that uses Kirby’s Fourth World characters and concepts; but that also isn’t it.

It’s simply that I remember reading those comics when they first came out, and I remember loving them. The books are cover-dated October, November, and December, 1980, meaning they’d have come out in the summer of that year. I was six. Like John’s experience with Little Lulu, when I found new copies, the draw of my childhood was overpowering. But Little Lulu’s frequently held to be some of the greatest kids’ comics ever done. These are just a few random issues of a mid-tier superhero book. Well-drawn, yes, but not spectacular. Still, I found that in part because the work is decent without being great, I could re-read them with a double vision, remembering how they seemed to me at six as much as I reacted to them in the present moment.

Obviously, I don’t remember entirely how these comics affected me all those years ago. Some things are lost entirely. But I think it’s the nature of the comics form to hold memories; it so often seems that when I reread a comic from when I was a kid that I’m brought back to the way I felt when I first read it, when all the characters were new and exciting and I had no idea of the contexts in which the stories were created.

Obviously, I don’t remember entirely how these comics affected me all those years ago. Some things are lost entirely. But I think it’s the nature of the comics form to hold memories; it so often seems that when I reread a comic from when I was a kid that I’m brought back to the way I felt when I first read it, when all the characters were new and exciting and I had no idea of the contexts in which the stories were created.

I think my response to comics art was different then, and much stronger. Nowadays when I read comics, or indeed when I look at non-comics art, I respond to the drawings as a work of creation; something an individual imagined, and then drew. At six, my responses were more complex. I understood that comics were fiction, were drawn by artists, were not real. But the sequence of images, overlapping and making not just a chronology but a coherent setting, led me imaginatively, instinctively, to respond to these pictures as windows upon some other reality. The form of comics relies on the juxtaposition of art in sequence; it relies on the reader to make the imaginative leap from one image to another, to fill in the blanks. The gutter between panels is a magic space, in which the reader creates the part of the story that’s not made. When a six-year-old is asked to do that, particularly with a story that’s already fantastic and highly-imaginative, something happens. The story in the child’s head becomes bigger than the story on paper. The fictive world becomes realer, and filled with matter beyond what is literally depicted — matter that is not concrete, not visualised nor articulated, but still imaginatively present.

I think something like the process of reading comics, of making that connective leap from one image to another, actually happens when reading prose, too. The reader connects clause to clause, sentence to sentence. Part of the characteristic of the style of a writer or a text is how easy or how difficult they choose to make that process. As with comics, the work as a whole is built out of fragments, which the reader combines; and much of the artistry lies in giving the reader the right fragments, and drawing attention to some while allowing others to be seeds for later.

All of which is to say that generally when I was a child I did more work for the stories I read than I realised. I remember loving the story in these Justice League comics because it felt huge. The reality is that while it does have a reasonable scope to it, it’s also nowhere near the clash of super-powered armies that I remembered.

All of which is to say that generally when I was a child I did more work for the stories I read than I realised. I remember loving the story in these Justice League comics because it felt huge. The reality is that while it does have a reasonable scope to it, it’s also nowhere near the clash of super-powered armies that I remembered.

Here’s what happens in the three books:

Once a year, the most unusual gathering of time and space takes place, a gathering of the greatest heroes of two parallel earths. On Earth-one, the world we know, those heroes are members of the … Justice League of America … On Earth-two, a world very much like our own, yet so different, those heroes belong to the … Justice Society … This year, they plan an unusual twist for their reunion … Half the members will journey to Earth-1, while the others will remain on Earth-2 to greet a contingent of Justice Leaguers … So they plan. Destiny, as usual, has other ideas.

That’s the text from the captions on the first page of 183, and they make for a concise set-up. The art helps sell it. The page is divided into three horizontal panels, the first showing the JLA heroes entering their transporter, the second showing the Justice Society characters entering their transporter, the third showing the two transporters in action, with a lot of Kirby Krackle. The first two panels have almost perfectly reversed composition — the JLA transporter’s on the right of the page, the Society’s transporter on the left. It’s a little touch, but by having the characters moving and looking in different directions, reflections of each other, it helps sell the idea of parallel worlds.

To expand on the set-up a little: At the time, DC’s cosmology was based around a variety of parallel earths. Their main publishing universe was Earth-1. Earth-2 was the world in which all the stories they’d published in the Golden Age (from the late 1930s up to the mid-50s or so) were set, meaning that it was a world that was still in the 1940s. Or at least, that’s what it had been originally. Not long before these Justice League issues came out, a new Justice Society series started, set in contemporary times. The old characters were aged, and new ones introduced.

To expand on the set-up a little: At the time, DC’s cosmology was based around a variety of parallel earths. Their main publishing universe was Earth-1. Earth-2 was the world in which all the stories they’d published in the Golden Age (from the late 1930s up to the mid-50s or so) were set, meaning that it was a world that was still in the 1940s. Or at least, that’s what it had been originally. Not long before these Justice League issues came out, a new Justice Society series started, set in contemporary times. The old characters were aged, and new ones introduced.

I know all this now. At the time I didn’t; and I didn’t need to know. The intro captions cleverly avoided having to explain all this backmatter. In a sense, this is contrary to the way super-hero comics have developed since — instead of trying to imply a larger world with random asides, or references to other characters, it doesn’t bother with what it doesn’t have to. Let the art build the world. Let the story focus on what it needs to, and nothing more.

And this worked. For the most part, at six I had no trouble grasping the idea of parallel earths and different heroes on different worlds. I do remember being confused by the fact that Wonder Woman wasn’t actually Wonder Woman — though, in fairness to my yonger self, the fact that the character in these three comics is the parallel-earth Wonder Woman really doesn’t affect the story at all. The point was clear: there are heroes I knew, and heroes I didn’t know; and some of those latter came from a world like our own but different.

And this worked. For the most part, at six I had no trouble grasping the idea of parallel earths and different heroes on different worlds. I do remember being confused by the fact that Wonder Woman wasn’t actually Wonder Woman — though, in fairness to my yonger self, the fact that the character in these three comics is the parallel-earth Wonder Woman really doesn’t affect the story at all. The point was clear: there are heroes I knew, and heroes I didn’t know; and some of those latter came from a world like our own but different.

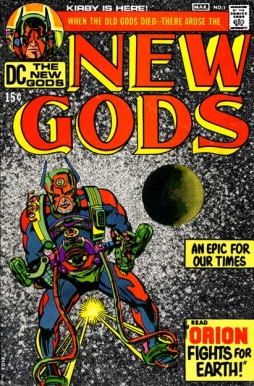

It’s a good mix of characters, too. From Earth-1, Superman, Batman, Green Lantern, and Firestorm; from Earth-2, Wonder Woman, Power Girl, Huntress, and Doctor Fate. They step into their respective transporters, which then go oddly wrong; they all find themselves in a mysterious empty city, identified by Superman as a place called New Genesis, the home of a race of superbeings called New Gods. The impetuous Firestorm goes exploring, and ends up in a fight with a mysterious brooding figure; the other heroes come to join the fight and defeat the unknown man, which is when his friends show up and explain what’s happening.

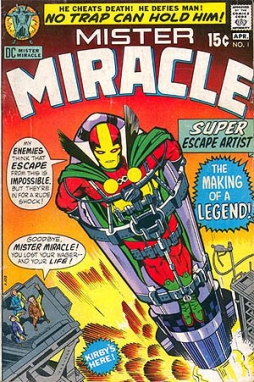

The mysterious figure is named Orion, and he’s the son of Darkseid, lord of the planet of Apokolips. Blissful New Genesis and hellish Apokolips were at war, with Orion fighting on the side of New Genesis; not long before, New Genesis had won the war, and Darkseid was killed. Now, though, Apokolips, in alliance with the Justice Society’s enemies the Injustice Society, has kidnapped almost the entire population of New Genesis. Only a few of the New Gods away exploring had been spared: Orion, the mysterious Metron, the dwarfish Oberon, and the husband-and-wife team of Mister Miracle and Big Barda. Now all the heroes have to team up, explore Apokolips, and defeat the bad guys.

Pacing in super-hero comics is different today than it used to be. Visual transitions are more important (as opposed to having disparate images stitched together by captions and dialogue), while there’s much more of an effort to avoid expository dialogue and generally create a sense of realism. Typically that results in a slower pace. The story elements and character introductions I’ve just described could easily take two issues to go through today. In 1980, they took 14 pages of a 25-page comic — and that’s counting two pages in which the heroes travel to Apokolips and split into teams. For a six-year-old, that was just about right. In those fourteen pages there are three teams of characters, a fight scene, exploration, some character-based dialogue, two different alien worlds, mystery, a hint of old enemies, and a desperate situation to be resolved. The story kept building, adding new wrinkles and new elements.

Pacing in super-hero comics is different today than it used to be. Visual transitions are more important (as opposed to having disparate images stitched together by captions and dialogue), while there’s much more of an effort to avoid expository dialogue and generally create a sense of realism. Typically that results in a slower pace. The story elements and character introductions I’ve just described could easily take two issues to go through today. In 1980, they took 14 pages of a 25-page comic — and that’s counting two pages in which the heroes travel to Apokolips and split into teams. For a six-year-old, that was just about right. In those fourteen pages there are three teams of characters, a fight scene, exploration, some character-based dialogue, two different alien worlds, mystery, a hint of old enemies, and a desperate situation to be resolved. The story kept building, adding new wrinkles and new elements.

Something else I notice now: At the time, and to some extent even today, conventional wisdom said that DC was the old man of the comics field next to Marvel’s young turk. The characters were older, the storytelling more conservative. But as I look at the characters in this story, I notice that over half of them had been created in the ten years before these issues were published — Firestorm, Power Girl, Huntress, and all the New Gods were 70s characters. While the New Gods were introduced in ‘71, the fact is that as young as I was when I first read these comics, three of the characters were younger still. So there was a certain currency to the book (and again this is a notable contrast to the present day; both DC and Marvel don’t seem able to create memorable characters the way they used to — and when they do create new characters, those characters almost always seem to play second-fiddle to the established star heroes in a way that isn’t really the case here).

I think that actually helped me as a child in reading the book. Again, it’s somewhat contrary to conventional wisdom, but the fact is that I always preferred reading about the new and unknown characters to those that I felt I understood. I knew what Superman and Batman could do. But this guy Firestorm, who was he? Ah, but wait, here’s a footnote, explaining his backstory. Say what you will, but these are accessible comics.

The writer of the book, Gerry Conway, was also the writer of DC’s then-new Firestorm book and of the Justice Society relaunch. He used to write for Marvel. So it’s not surprising that some of the characters seem to sound more like angsty Marvel characters than traditional DC jut-jawed heroes. Leave aside Firestorm’s Human Torch-like rashness in going exploring on his own. After defeating Orion, Green Lantern reflects: “I know we just won … so how come I feel lousy? After all, seven against one is pretty crummy odds.”

The writer of the book, Gerry Conway, was also the writer of DC’s then-new Firestorm book and of the Justice Society relaunch. He used to write for Marvel. So it’s not surprising that some of the characters seem to sound more like angsty Marvel characters than traditional DC jut-jawed heroes. Leave aside Firestorm’s Human Torch-like rashness in going exploring on his own. After defeating Orion, Green Lantern reflects: “I know we just won … so how come I feel lousy? After all, seven against one is pretty crummy odds.”

It’s a character moment that doesn’t lead to anything, and doesn’t seem especially natural coming from Green Lantern (knowing that character’s background as I do now). But it also feels, or felt, like something in tune with the times: a skepticism about the use of force. Heroes fight, but doubt the rightness of fighting. At six, I was used to seeing that. Morality aside, at that age, it created an effective illusion of depth — characters doing something, but thinking about what they were doing, criticising themselves for their own actions. Generally there’s not much character depth or development over the course of the three issues; there isn’t even a hint of any kind of consistent arc. The characters are colourful widgets, moving the plot forward, kept distinct from each other with moderately distinctive speech patterns and a few nods here and there towards the idea of personality.

Perhaps for that reason, though, when the characters do get a moment to express themselves, those characterisations stuck with me. When Superman mentions that New Genesis is home of the New Gods, Earth-2 Wonder Woman gets a panel to rant that “The only gods I acknowledge are the gods of Mount Olympus … and he who is the only true “god” … whose nature remains unknown.” Leaving aside the questions of to what extent Greek philosophy had envisioned a monotheistic god, and of whether an Amazon would conceive of a single deity in patriarchal terms, that panel set up who Wonder Woman was. It told me that she was connected with the Olympian gods, and how she felt about them. It gave me a glimpse of a severe, slightly angry character that stuck with me through the rest of the story — even though there was no development and no payoff, no further manifestation of real individuality from the character in these issues. That one glimpse was enough for me as a six-year old to identify her as a character, to feel like I’d come to know her, to get a sense of how she was reacting to the events around her. An illusion, certainly. But because these comics presented me with enough matter to create these illusions for myself, they worked in a way better-crafted stories often did not.

Plot-wise, once the heroes get to Apokolips, they divide into their four teams and go about their various missions, with Metron, the mentor who’d given them their targets, remaining behind. Batman, Mister Miracle, and the Huntress sneak into the imperial palace; Green Lantern, Doctor Fate, and Oberon investigate a barracks where a high-value prisoner’s being held; Superman, Wonder Woman, and Big Barda attack the school where the New Genesis children are being held; and Orion, Firestorm and Power Girl check out a major construction project (where it turns out the Injustice Society’s working on a plan to bring Darkseid back to life). The teams have one member of each of the three groups apiece, which you’d think would lead to some interesting back-and-forth about powers and abilities; it doesn’t, for the most part, though there is an engaging sense of newness to some of the interactions — characters who don’t know who every other character is, characters who don’t have involved pasts with each other.

Plot-wise, once the heroes get to Apokolips, they divide into their four teams and go about their various missions, with Metron, the mentor who’d given them their targets, remaining behind. Batman, Mister Miracle, and the Huntress sneak into the imperial palace; Green Lantern, Doctor Fate, and Oberon investigate a barracks where a high-value prisoner’s being held; Superman, Wonder Woman, and Big Barda attack the school where the New Genesis children are being held; and Orion, Firestorm and Power Girl check out a major construction project (where it turns out the Injustice Society’s working on a plan to bring Darkseid back to life). The teams have one member of each of the three groups apiece, which you’d think would lead to some interesting back-and-forth about powers and abilities; it doesn’t, for the most part, though there is an engaging sense of newness to some of the interactions — characters who don’t know who every other character is, characters who don’t have involved pasts with each other.

I remembered the story as cutting cleverly back and forth between the teams, but in fact the cuts are very simple. Each team gets a couple pages to fill out 183; each team gets one scene in 184; effectively each team gets a scene in 185, along with a recap scene in which Metron muses about what he should do, which is followed by a scene with the villains bickering. It was something of a tradition for both Justice Society and Justice League adventures to involve the group splitting into teams; it must have made for an easier story to write, with smaller groups of characters involved. Typically, though, those stories involved the group re-uniting at the end for an explosive finale. That doesn’t happen here. The different plot strands don’t really connect, and two of them have no evident purpose at all.

The pacing of the individual scenes is fine, and the way they give you all the elements you want in a super-hero book — fight scenes, tense sneaking around, cliffhanger endings — but the resolution of the whole story fails to cohere neatly. It’s a smoke-and-mirrors tale; there’s no coherent structure, and no real attempt at a point.

What’s most surprising to me as I re-read the comics is to find that the heroes lose. The cliff-hanger at the end of the second part of the story has Batman’s group discovering that Darkseid’s planning the destruction of Earth-2 by blasting it with a ray that’ll move Apokolips into the Earth’s place; despite everybody’s best efforts, the ray is fired — but Metron’s re-oriented it behind the scenes to blast Darkseid, killing him again. It’s a literal deus ex machina (neo deus ex machina?), and the story ends four panels later. The second most surprising thing is to note that the story’s really about Earth-2 more than Earth-1; that’s the planet endangered by Darkseid, and that’s where he finds his human conspirators.

What’s most surprising to me as I re-read the comics is to find that the heroes lose. The cliff-hanger at the end of the second part of the story has Batman’s group discovering that Darkseid’s planning the destruction of Earth-2 by blasting it with a ray that’ll move Apokolips into the Earth’s place; despite everybody’s best efforts, the ray is fired — but Metron’s re-oriented it behind the scenes to blast Darkseid, killing him again. It’s a literal deus ex machina (neo deus ex machina?), and the story ends four panels later. The second most surprising thing is to note that the story’s really about Earth-2 more than Earth-1; that’s the planet endangered by Darkseid, and that’s where he finds his human conspirators.

So why did these books appeal to me so much when I was a child, that thirty years later I remembered them so strongly?

There is some material in these books that seems specifically aimed at children. Superman’s team of heroes has to sneak into the wicked school run by Granny Goodness, a kind of indoctrination camp for children — and I’d never noticed before how powerful that image of school is, how much it was likely to resonate with kids. The heroes find a group of children guerillas, which is a nice idea, and I think as a child I accepted it; I don’t remember it resonating with me, especially, but it might have — especially in scenes where the children are pushed around by adult guards, which is something universal in the experience of childhood. On the whole, though, I don’t think the books worked because they were especially well-designed for children.

I think the emotion I felt, in recalling them before rereading them, was a kind of imaginative awe; they’d activated something in my imagination when I was young. Rereading the comics now, the scope of events isn’t what I remembered. A major battle that I thought I recalled, between Doctor Fate and Green Lantern on one side and a mass of para-demons on the other, is nothing more than a space-filling go-nowhere fight scene. This is not, after all, that big a story.

I think the emotion I felt, in recalling them before rereading them, was a kind of imaginative awe; they’d activated something in my imagination when I was young. Rereading the comics now, the scope of events isn’t what I remembered. A major battle that I thought I recalled, between Doctor Fate and Green Lantern on one side and a mass of para-demons on the other, is nothing more than a space-filling go-nowhere fight scene. This is not, after all, that big a story.

Of course, when I first read it, I wasn’t very big either. I had to grow to understand it, to contain it. Here’s a quick look at some of the words and concepts within the first dozen pages of issue 183, a comic which made perfect sense to me at age six: “parallel earths,” “destiny,” “[new] genesis,” “satellite,” “universes,” “malfunctioned,” “transmatter cube,” “misfit,” “reponsibilities,” “mount olympus,” “composite,” “fused,” “nuclear,” “personality,” “emergency,” “fortune,” “micro-seconds,” “malevolent,” “dilemma,” “rationality,” “electronic,” “miraculous,” “heritage,” “monstrous.” Florid captions on page 13 give us “atavistic,” and “some monstrous boil in the eye of God … glowing and pustulant with evil.” I do remember being baffled by a reference to New Genesis seeming as deserted as “Pasadena after the Rose Bowl.” 184 is titled “Apokolips Now!”, which would have meant nothing to me at the time; but, looking at the cover, I have a vague memory of my father patiently explaining what ‘apocalypse’ meant, and noting that it was misspelled.

Vocabulary, concepts, even (arguably) my understanding of the world had to expand to make sense of this story. Of course it felt huge. I was seeing third-hand genre ideas for the first time, and they were all new to me. Still, when all’s said and done, I wonder whether it wasn’t the flaws in the story’s construction that helped the story stick.

I think from a technical point of view, in terms of introducing character moments, in terms of balancing different kinds of scenes, in terms of keeping different things in motion, the story gets worse as it goes along. 183 is excellent; 184 keeps the momentum, for the most part; 185 doesn’t quite bring everything together, and then just stops with no emotional payoff. Rereading it, I find that 183 stuck vividly in my mind, not just the panels but the way I felt about them; and then that was a bit less true for 184; and it wasn’t true of 185 very much at all. I remember the panels and the pages, but I don’t feel the sense of wonder I got from 183.

I think from a technical point of view, in terms of introducing character moments, in terms of balancing different kinds of scenes, in terms of keeping different things in motion, the story gets worse as it goes along. 183 is excellent; 184 keeps the momentum, for the most part; 185 doesn’t quite bring everything together, and then just stops with no emotional payoff. Rereading it, I find that 183 stuck vividly in my mind, not just the panels but the way I felt about them; and then that was a bit less true for 184; and it wasn’t true of 185 very much at all. I remember the panels and the pages, but I don’t feel the sense of wonder I got from 183.

I suspect now that as much as I was unconsciously doing some imaginative heavy lifting, investing the early parts of the story with meaning, the structure of the scenes and the story allowed that to happen. The later parts of the story don’t build off of what came before, and don’t really resolve in any satisfying way, and therefore didn’t give me the same imaginative experience. But then it also means that the story was always something of an enigma for me: it built up such momentum in the early going — how could it tail off into nothing? That energy, that sense of wonder, had to go somewhere.

So it seemed when I was six. In my late thirties, I look at the books and the difference between beginning and ending seems less clear. The characterisation is random all the way along, the use of the Fourth World material is nice but not terribly imaginative, and if the ending is weaker than the opening scenes, well, endings usually are the toughest bit to pull off. I think if I came across these comics for the first time now, I’d miss the way the first issue built, I’d miss the balancing of concepts, and I probably wouldn’t notice the quick and competent introduction of so many characters and settings.

All of which is to say: remembering my reaction when I was a child gives me a better perspective on these comics, and what’s in them, and what they do and don’t do. It is perfectly true that different people will react differently to the same story; but it’s also true that we become different people as we live our lives. There’s an aphorism that you never cross the same river twice, for you are not the same person and the river is not the same river; it is also true that we never read the same tale twice, for we are never the same person as read it the first time.

And, perhaps, the tales are not the same tales. What we learn about them changes them. In the case of comics, what happens to the characters in later stories can change the way we see them earlier on. It’s almost startling, and certainly refreshing, to see Power Girl and to some extent Huntress depicted without explicit sexualisation. It’s nice to see Doctor Fate and Firestorm as simple, easily-understood character concepts, without the many revisions that have been laid over them in recent years. And something else: these days, my favourite DC super-hero character, easily, is Mister Miracle. It’s interesting to read this story from a time before the character had come to mean much to me, before I’d read Kirby’s original Fourth World work.

And, perhaps, the tales are not the same tales. What we learn about them changes them. In the case of comics, what happens to the characters in later stories can change the way we see them earlier on. It’s almost startling, and certainly refreshing, to see Power Girl and to some extent Huntress depicted without explicit sexualisation. It’s nice to see Doctor Fate and Firestorm as simple, easily-understood character concepts, without the many revisions that have been laid over them in recent years. And something else: these days, my favourite DC super-hero character, easily, is Mister Miracle. It’s interesting to read this story from a time before the character had come to mean much to me, before I’d read Kirby’s original Fourth World work.

Times pass and lives change. I remember my parents were skeptical of the value of reading comics. My mother in particular didn’t think the writing was very good; and, in fairness, she was often correct. On the other hand, she’s now a fan of the TV show Law & Order — including episodes written by none other than Gerry Conway. Were comics better than anyone thought, or is TV worse? Or both? Or has Conway gotten that much better? I don’t know. What you look for in writing changes. What you’re capable of recognising changes. Can an adult really judge the value of a story aimed at a child? Perhaps not.

Only, with a bit of luck, we can remember what it was we found once. We can remember what stories did for us. We never enter the same river twice, except in memory; but it is only through memory, and through crossing and recrossing the waters, that we can come to understand the idea of that river. And if most comics are humbler things than rivers, their waters more still, they are correspondingly better able to reflect us, and what we once were.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

A marvelous post, Matthew. While I was looking forward to the second installment of your Romanticism and fantasy series, I’m glad you took time off for this one.

For me, the heart of the post was these lines:

> the sequence of images, overlapping and making not just a chronology but a coherent

> setting, led me imaginatively, instinctively, to respond to these pictures as windows

> upon some other reality… The gutter between panels is a magic space, in which the

> reader creates the part of the story that’s not made.

Yes. Yes — exactly.

You could easily make an argument then that the true magic of comics occurs in the gutters, in those interstitial moments created by the engine of belief. Today, I see nothing more than what’s on the page. But as a child, I lived in the moments between the panels. I glimpsed the whole world.

No, I suppose that’s not true. If it were completely true, then I’d probably stop reading comics. There ARE comics today than can drag me into their world (I was charmed and won over just last week by, of all things, an issue of AMAZING SPIDER-MAN). But it’s so much harder now, and those moments much more fleeting.

Before I start to sound like just another cranky old man longing for the wonder of childhood, I should say that I wouldn’t trade my reading experience with my 10-year-old self.

Sure, I was completely swept away by comics at that age, and rarely am now. But today I see so much more — the recognizable line of a favorite artist, the subtle (and not so subtle) changes in character with changing writers. I’m far more aware of the craft of comics now, and that brings its own rewards.

[…] the text before me? There’s a fairly widespread phenomenon among readers of returning to books (or comics) we read when we were children and finding them smaller; the emotional power lessened, long […]