Lord Dunsany and “The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save For Sacnoth”

Lord Dunsany’s short story “The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save for Sacnoth” has been called the first sword-and-sorcery story ever written. That attribution has been contested elsewhere, though. I don’t particularly intend to grapple with the question — it seems to me that genres are defined by conventions, which is to say by expectations held by a reader; whether a story fits a genre therefore depends on whether the conventions it uses are the ones that the individual reader expects, and while many stories use conventions in such standard ways that there’s broad agreement about sort of tale they are, some, like ‘Sacnoth,’ will vary in definition from person to person. But as a story, I think “Sacnoth” is worth discussing. Like most of Dunsany’s early short stories, it’s really quite brilliant.

Lord Dunsany’s short story “The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save for Sacnoth” has been called the first sword-and-sorcery story ever written. That attribution has been contested elsewhere, though. I don’t particularly intend to grapple with the question — it seems to me that genres are defined by conventions, which is to say by expectations held by a reader; whether a story fits a genre therefore depends on whether the conventions it uses are the ones that the individual reader expects, and while many stories use conventions in such standard ways that there’s broad agreement about sort of tale they are, some, like ‘Sacnoth,’ will vary in definition from person to person. But as a story, I think “Sacnoth” is worth discussing. Like most of Dunsany’s early short stories, it’s really quite brilliant.

(You can find it online here, and if you’ve not read it before I strongly urge you to give it a try.)

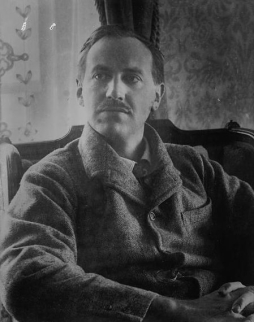

Some background: Lord Dunsany was an Anglo-Irish peer, born in 1878; he died in 1957. He was a prolific writer across a wide range of genres and forms, including plays, autobiography, realistic novels, poems, novels, essays, and more. He wrote some wonderful fantasy novels, such as The King of Elfland’s Daughter and The Charwoman’s Shadow, as well as work which seemed to hover on the edge of fantasy and realism, such as The Curse of the Wise Woman. He’s best known, and perhaps best regarded, for the eight volumes of fantasy short stories he wrote near the start of his career. It’s been said, by Lin Carter among others, that the poor critical reception of those stories led him to try other forms.

Some background: Lord Dunsany was an Anglo-Irish peer, born in 1878; he died in 1957. He was a prolific writer across a wide range of genres and forms, including plays, autobiography, realistic novels, poems, novels, essays, and more. He wrote some wonderful fantasy novels, such as The King of Elfland’s Daughter and The Charwoman’s Shadow, as well as work which seemed to hover on the edge of fantasy and realism, such as The Curse of the Wise Woman. He’s best known, and perhaps best regarded, for the eight volumes of fantasy short stories he wrote near the start of his career. It’s been said, by Lin Carter among others, that the poor critical reception of those stories led him to try other forms.

But then on the other hand it does seem that his stories were widely appreciated. He was a strong influence on H.P. Lovecraft; Tolkien also enjoyed him. Aleister Crowley, as always looking on the bright side of things, observed in his novel Moonchild that “Lord Dunsany’s stories are the perfect prose jewels of a master cutter and polisher, lit by the rays of an imagination that is the godlike son of the Father of All Truth and Light; but if he kept them to himself, they would be the symptoms of an incurable lesion of the brain.” Crowley also wrote Dunsany a fan-letter in which he incidentally criticised Dunsany’s treatment of hashish-smoking as not being realistic enough.

At any rate, Crowley was wrong about at least one thing: though Dunsany’s stories seem to be supremely-crafted masterpieces of style, he apparently wrote them in one draft. Dunsany had a natural ear for rhythm and the colour of language; the style that came so naturally to him has proven almost impossible to replicate — much as other writers have tried. It was a style shaped partly by the King James Bible, the Arabian Nights, and Herodotus, as well as Poe and the Grimms and Swinburne, but mostly I think by an instinctive feel for the beat and swing of words. He said of one phrase (everything after the second comma in “though all the mundane plain, its rivers and mountains, lay between Shepperalk’s home and the city he sought”) that he could not have written it “had I not that day been riding a fox-hunt, for the rhythm is that of a gallop.” There’s something purely poetic in that, the taking of the beat of everyday experience and turning it into language.

That gift for language, allied with a wide-ranging and unpredictable imagination, made Dunsany not only one of the first of modern fantasy writers, but also I feel one of the best. At the same time, Dunsany had a keen eye for absurdity. As a result, one of the characteristics of his writing, and one of its most fascinating aspects, is the way he deftly handles the tension between fairy-tale wonder and an ironic deflation of that sense of wonder. Many of his wilder stories come close to turning into outright parodies by wildly exaggerating their fantastic aspects; but then also many have an ending that negates the fantasy of the preceding story, suggesting it was a dream or delusion. “Sacnoth” does both. But the effect is still of fantasy, overall; the wonder of the tale is internally self-consistent, and so insists on its validity. Whether the events of the story are true or not, it is true that it works as a story.

That gift for language, allied with a wide-ranging and unpredictable imagination, made Dunsany not only one of the first of modern fantasy writers, but also I feel one of the best. At the same time, Dunsany had a keen eye for absurdity. As a result, one of the characteristics of his writing, and one of its most fascinating aspects, is the way he deftly handles the tension between fairy-tale wonder and an ironic deflation of that sense of wonder. Many of his wilder stories come close to turning into outright parodies by wildly exaggerating their fantastic aspects; but then also many have an ending that negates the fantasy of the preceding story, suggesting it was a dream or delusion. “Sacnoth” does both. But the effect is still of fantasy, overall; the wonder of the tale is internally self-consistent, and so insists on its validity. Whether the events of the story are true or not, it is true that it works as a story.

The story of “Sacnoth” begins with the village of Allathurion suffering from bad dreams; the local magician finds out that they were sent by an evil wizard named Gaznak, who lives in a fortress that cannot be successfully invaded except by the wielder of the sword Sacnoth. A young man, Leothric, asks further about Sacnoth, and the magician tells him that it’s a piece of steel in the back of an iron dragon. To defeat Gaznak, Leothric has to kill the dragon and have Sacnoth forged into a proper sword; then he has to make his way to the wizard’s castle, and overcome all the obstacles therein. Finally, Leothric fights the wizard himself sword-to-sword, and defeats him. At which point the glory of the fortress vanishes. The abysses over which it was built were “closed up suddenly as the mouth of a man who, having told a tale, will for ever speak no more.” And then Dunsany tells us:

This is the tale of the vanquishing of The Fortress Unvaquishable, Save For Sacnoth, and of its passing away, as it is told and believed by those who love the mystic days of old.

Others have said, and vainly claim to prove, that a fever came to Allathurion, and went away; and that this same fever drove Leothric into the marshes by night, and made him dream there and act violently with a sword.

And others again say that there hath been no town of Allathurion, and that Leothric never lived.

Peace to them. The gardener hath gathered up this autumn’s leaves. Who shall see them again, or who wot of them? And who shall say what hath befallen in the days of long ago?

I think there are a number of different ways to take this epilogue. You can say, for example, that Dunsany presents two separate ways by which the story didn’t happen. But then you can also say that the second debunking attitude, that Allathurion never existed, suggests that the first debunkers, who claim to have proved that Allathurion was subject to a fever, were talking nonsense; which itself suggests that the debunking comes from a need to have the story debunked, and so undermines the second attitude as well. The apparent non-sequitur ending leads into what seems a pat moral; but then, the answer to the question “who shall say what hath befallen in the days of long ago” can have a few different answers. Is it the historian? Or is it the storyteller? Because the story we’ve just read has been the work of one who has been saying what befell in the days of Allathurion.

As I say, it’s the tension between wonder and irony that largely defines Dunsany to me. I think at heart Dunsany’s work is driven by wonder and fantasy, and by language; but I think he was also a skeptic, and so doubted even the myths he made himself, and built in ways by which they could be deconstructed. I think that has the overall effect of transcending both myth and skepticism; like Blake resolving the contraries of innocence and experience by moving beyond both, Dunsany’s fantasies seem to include within them both the suspension of disbelief and the lack of same. They are larger than either alternative.

As I say, it’s the tension between wonder and irony that largely defines Dunsany to me. I think at heart Dunsany’s work is driven by wonder and fantasy, and by language; but I think he was also a skeptic, and so doubted even the myths he made himself, and built in ways by which they could be deconstructed. I think that has the overall effect of transcending both myth and skepticism; like Blake resolving the contraries of innocence and experience by moving beyond both, Dunsany’s fantasies seem to include within them both the suspension of disbelief and the lack of same. They are larger than either alternative.

But I think that the ultimate explanation for this seemingly-equivocal ending can be found if we move backwards into the story itself. To start, it’s worth pointing out that, as with much of Dunsany’s other work, the tale reads strangely because it avoids certain formulas that I think have come to be taken for granted in much fiction. There’s no inwardness to Leothric; he happens to be a guy that asks about the sword Sacnoth at the right moment, and happens to be the sort of young man that has the physical gifts to get the sword and use it effectively. The various trials he goes through could perhaps be seen as symbols of some sort of internal quest, but I don’t see much of a hint that they’re intended to be taken as such. And yet they’re compelling; the rules we think we know of the importance of character and of selecting incident to further a theme are casually disregarded, and as a result the story feels free and unpredictable as a dream.

Which is, I believe, the point. The title of the story is “The Fortress Unvanquishable, Save for Sacnoth” — it’s not the sword that’s key, nor the iron dragon from whence it comes, nor even the hero. It’s the fortress. The hero goes to the fortress to put a stop to bad dreams; when he kills the wizard, the fortress vanishes, because it and everything in it were only the wizard’s dreams. And if the vanished abysses, upon which the castle was built, are likened to the storyteller’s mouth, then the dreamer and storyteller are one.

To say that Leothric was gripped by a fever is almost redundant; he was fighting bad dreams. The story follows him as he goes to the heart of nightmare, and has a confrontation there that, symbolically or literally, overcomes the dream. But then doing so opens up the possibility that he, his quest, and his whole village, are themselves nothing more than dreaming. Overcoming the fortress means overcoming themselves. Silencing the story means silencing themselves. But then so long as the story is told, then for so long Allathurion is saved.

To say that Leothric was gripped by a fever is almost redundant; he was fighting bad dreams. The story follows him as he goes to the heart of nightmare, and has a confrontation there that, symbolically or literally, overcomes the dream. But then doing so opens up the possibility that he, his quest, and his whole village, are themselves nothing more than dreaming. Overcoming the fortress means overcoming themselves. Silencing the story means silencing themselves. But then so long as the story is told, then for so long Allathurion is saved.

I have no idea whether Dunsany consciously intended this. But I think it’s how the story reads. I think it’s a story about dreams, which I think was a major concern of Dunsany, perhaps precisely because he was in many ways a skeptic. I think it’s a story about confronting nightmares, and taking control of one’s dreams and fantasies, and the way in which one wakes.

So with all this being said, is the story sword-and-sorcery? As I said before, I think it depends on what conventions define sword-and-sorcery for you. It is about a single hero with a sword slaying a dragon, adventuring through the hazards of a wondrous fortress, and finally slaying an evil wizard in hand-to-hand combat. But then it’s also written in a high, mythic style. Dunsany actually had a good eye for practical realities, but in this story almost everything that happens is told in the language of epic. It also has an ending that can be read as undercutting the story in a way that’s unusual for sword-and-sorcery.

Personally, I think it’s more like sword-and-sorcery than it is unlike it. Besides the plot elements I mentioned above, it also has a number of other fantasy staples; a semi-sentient sword, a scene where the great sword is forged, an evil giant spider, great abysses, vampires, even, unusual for Dunsany, the temptation of the male hero by a harem of sinister women: “Perhaps Leothric had been tempted to tarry had they been human women, for theirs was a strange beauty, but he perceived that instead of eyes they had little flames that flickered in their sockets, and knew them to be the fevered dreams of Gaznak.” For me, all this adds up, and it feels like sword-and-sorcery, particularly compared to Dunsany’s other work; but I can see the argument against.

Personally, I think it’s more like sword-and-sorcery than it is unlike it. Besides the plot elements I mentioned above, it also has a number of other fantasy staples; a semi-sentient sword, a scene where the great sword is forged, an evil giant spider, great abysses, vampires, even, unusual for Dunsany, the temptation of the male hero by a harem of sinister women: “Perhaps Leothric had been tempted to tarry had they been human women, for theirs was a strange beauty, but he perceived that instead of eyes they had little flames that flickered in their sockets, and knew them to be the fevered dreams of Gaznak.” For me, all this adds up, and it feels like sword-and-sorcery, particularly compared to Dunsany’s other work; but I can see the argument against.

What I think is relevant about the story, what I think makes it and Dunsany’s writing in general so strong, is the ability to bind together high fantasy and high irony with beautiful language. The variety and invention of the story is astounding, but it really succeeds because of the way it is told. It’s a masterpiece of pure form. It’s difficult even to learn from, because it is purely individual, and carried so much by its inimitable style. But at the same time, it also has a sense of freedom to it: anything can happen. This is in a sense fantasy at its purest. And, in many ways, at its finest.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His blog is Hochelaga Depicta.

People with e-readers might enjoy downloading the collection (for free) from feedbooks.

I look forward to it myself — I’ve never read any Dunsany.

Hear, hear! Kudos on a brilliant article that explores a brilliant piece of fantasy. This is definitely one of Dunsany’s many masterpieces of the form. I am one of those who considers this indeed the first “sword and sorcery” tale.

“The Sword of Welleran” is another nigh-perfect tale, as is “The Hoard of the Gibbelins,” “The Bride of the Man-Horse,” “How One Came, As Was Foretold, To the City of Never,” “The Relenting of Sardinac,” “The Fall of Babbulkund,” “Idle Days on the Yann,” “The Avenger of Perdondaris,” “Carcassonne,” “The Distressing Tale of Thangobrind the Jeweler,” “The Sword and the Idol,” “In Zaccarath,” “Poltarnees, Beholder of Ocean,” and “The Dwarf Holóbolos & The Sword Hogbiter,” as well as many other fine tales. Not to mention his amazing novel “The King of Elfland’s Daughter.” Sheer storytelling magic at its most powerful, and language at its most gorgeous. In Dunsany’s hands, metaphors are spells of enchantment, a turn of phrase is an abiding image beyond the terrestrial fields, and myth itself breathes with timeless power.

I’ve said it before, but it bears repeating. Every fantasy writer should read Dunsany.

Great post, Matthew!

JF

Ah, the style of the “First Terrible Fate that Awaiteth Unwary Beginners in Fantasy”!

I think it can be beneficial once you manage to digest the lessons learned by writing thirteenth-rate imitiations (since no one does better than that imitiating Dunsany).

Oh, Dunsany has many lessons to teach. Most of all, how to write SIMPLY yet effectively. How to let figurative language work its magic, without drowning your prose in adjectives and adverbs. How to speak plainly and timelessly about mythic and supernatural elements. Economy of language, facility of metaphor and simile…the basic rule of great writing: Keep it simple.

This is a hard lesson to learn for most young writer (I know it was for me). Once you “get it,” it transforms everything. Less is more, and all that jazz.

Wonderful subject Surridge!

Dunsany is one of my most cherished writers. Of anything in any time in any place in any tongue.

I would like to draw attention, to your statement that Dunsany was a skeptic.

I certainly agree, and it is that epilogue which gets to the soul of the skeptic as it originated in ancient Greece.

‘Nothing can be known not even this’

Sound like anyone you’ve read before?

Hint; that’s not a quote from Dunsany…