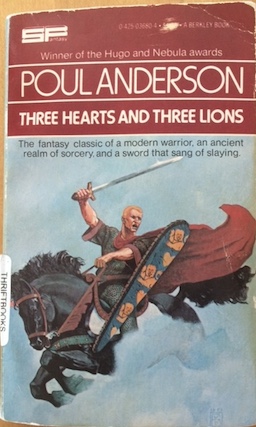

Chaotic and Lawful Alignments in Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions

I’m willing to bet that Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions published in 1953 in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (and Anderson’s close friend and frequent collaborator Gordon R. Dickson’s St. Dragon and the George, published likewise in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction at about the same time – later republished as The Dragon and the George) owes quite a bit to Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. And Anderson doesn’t disguise this, for he at least once overtly references Twain’s historical romance when he has his protagonist, Holger Carlsen (a “Carl” again!), unconvincingly scare away a band of barbarians by using his tobacco pipe to blow smoke out of his mouth. The work further encourages comparisons to Twain’s book through Holger’s use of other “Enlightenment” tricks in a secondary world, and Anderson uses bookends reminiscent of Twain’s. Anderson’s bookends here are worth a closer look.

I’m willing to bet that Poul Anderson’s Three Hearts and Three Lions published in 1953 in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction (and Anderson’s close friend and frequent collaborator Gordon R. Dickson’s St. Dragon and the George, published likewise in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction at about the same time – later republished as The Dragon and the George) owes quite a bit to Mark Twain’s A Connecticut Yankee in King Arthur’s Court. And Anderson doesn’t disguise this, for he at least once overtly references Twain’s historical romance when he has his protagonist, Holger Carlsen (a “Carl” again!), unconvincingly scare away a band of barbarians by using his tobacco pipe to blow smoke out of his mouth. The work further encourages comparisons to Twain’s book through Holger’s use of other “Enlightenment” tricks in a secondary world, and Anderson uses bookends reminiscent of Twain’s. Anderson’s bookends here are worth a closer look.

Holger Carlsen’s history, as relayed by an unspecified narrator, funhouse-mirrors Anderson’s personal history. In a book profiling Supernatural Fiction Writers, Ronald Tweet reports that Anderson was born to Danish parents and lived in Denmark for a while previous to WWII. Holger of Three Hearts and Three Lions is a Dane who, after wandering Europe, starts attending an Eastern university in the U.S. When WWII breaks out, he goes back to Denmark, where, through fairly compressed and elliptical telling, the narrator says that Holger eventually ends up in a pistol fight with Germans. At this point, “all his world [blows] up in flame and darkness.” And Holger finds himself in a fantasy world.

In light of Anderson’s own biographical information, one is tempted to believe that much of this work is the result of a highly personal fantasy, a kind of daydream out of which many fantasies certainly must arise. I’m sure that most of us have fantasized about being an important person in an important place – If only we could get there, somehow!