Fantasy Clichés Done Right

Like all genres of fiction, fantasy has a growing list of clichés and played-out tropes: the orphaned farm boy who’s actually the chosen one, the quest for a magical artifact to save the world, the generic medieval European setting, the Tolkien-lite denizenry of humans and elves versus orcs, goblins, and trolls…. On one hand, it’s surprising to see these tropes crop up over and over again. Authors are supposed to be imaginative. Is it really that hard to come up with original ideas? On the other hand, it makes a good bit of sense to see certain recurring tropes. Fantasy is, after all, rooted in mythology, and one can make a strong case that fantasy taps into symbols and archetypes coded into the human psyche, whether we’re talking about Joseph Campbell’s Hero’s Journey or the simple Jungian archetype of the shadow representing the basest of human instincts.

In practice, of course, the truth lays somewhere in the middle. Mediocre writers reuse certain tropes and make them cliché because they do nothing new with them. Expert writers create new tropes or take old ones and make them new in the context of unique characters and original words.

This holds true not only for the classics, but also for new fantasy fiction, as author James P. Blaylock discovered when he was a judge for the World Fantasy Awards in 2012. “I was certain that zombies and vampires had been so overworked that I’d have no interest in any of them,” he recalls, “but then I ended up putting one of each on my shortlist: ‘From the Teeth of Strange Children’ by Lisa Hannett and ‘Younger Women’ by Karen Joy Fowler.”

With this idea in mind, here are a dozen or so books that transcend the tired fantasy clichés they utilize, as recommended by an assortment of writers in the genre. (The list is hardly comprehensive, mind you, so make sure to add your recommendations in the comments.)

[Click on any of the images for bigger versions.]

Tim Powers, World Fantasy Award winning author

Well, there’s the “mysterious magical artifact,” which has variously been a sword, a ring, a model ship, an ornament broken from a railing in an alien world — and of course it proves to be much more significant than it initially appears to be.

Well, there’s the “mysterious magical artifact,” which has variously been a sword, a ring, a model ship, an ornament broken from a railing in an alien world — and of course it proves to be much more significant than it initially appears to be.

James Branch Cabell turned this idea on its head in his novel The Cream of the Jest (1917), in which the hero finds half of a metal disk, which he believes is the fabled Sigil of Scoteia, and it allows him to meet the woman he loves in various historical periods in his dreams — but it turns out that the half-disk is just the broken lid of a cold cream jar (a sort of reference to the book’s title).

And Vonnegut used a similar deflation effect when, in The Sirens of Titan (1959), all of human civilization and culture turns out to have been guided by aliens to ultimately produce one pocket-sized strip of metal which is a spare part for a stranded alien’s space ship. The construction of Stonehenge and the Pyramids and the Great Wall of China were actually driven by the aliens’ influence to give the stranded guy messages — which consisted of things like “Pretty Soon,” and “Any Time Now.”

Misty Massey, author of Mad Kestrel and editor of the forthcoming anthology Tales of the Weird Wild West

I’m sure it’s a result of growing up geeky, but lots of stories are all about regular people finding their way to fantasy worlds via magical portals. Generally people who find themselves in an unfamiliar culture don’t succeed that well and that quickly, so adding magic to the mix seems like it would make things harder.

Which is why I liked Lev Grossman’s The Magicians series. Quentin is unhappy in the real world, and finds his way to magical Fillory, eventually becoming a king. But that isn’t the end of the story — being king, even in a fantasy world, is dull and tedious and as unfulfilling as the real world was. It’s only when Quentin realizes that happiness is further away than one portal crossing that he discovers the path to his own happy ending.

Mary Moore, author and literary agent specializing in fantasy and science fiction

One of my favorite classic series that takes fantasy clichés and turns them on their head is The Enchanted Forest Chronicles by Patricia C. Wrede. She pulls from the classic “Princess kidnapped by a dragon and needs to be rescued by a knight,” but changes it, so that instead of a helpless blonde beauty being carried away by an evil dragon, the princess is in fact tall, lanky with black hair who decides she’s bored with castle life and runs away to be a dragon’s maid. Seriously.

One of my favorite classic series that takes fantasy clichés and turns them on their head is The Enchanted Forest Chronicles by Patricia C. Wrede. She pulls from the classic “Princess kidnapped by a dragon and needs to be rescued by a knight,” but changes it, so that instead of a helpless blonde beauty being carried away by an evil dragon, the princess is in fact tall, lanky with black hair who decides she’s bored with castle life and runs away to be a dragon’s maid. Seriously.

And because she wants to be there, she spends quite a bit of time (hilariously) discouraging the multitudes of would-be-rescuers that come her way. The dragons are intelligent and the witch has glasses and nine non-black cats. It’s a fantastic MG-YA read for kids who want to read something other than the pretty princess fantasy.

Another, more modern and adult, series that does a good job of creating an unique world out of a cliché trope is the Elemental Blessings by Sharon Shinn (including Troubled Waters and Royal Airs). The trope that wizards/witches have control of the four magical elements — earth, wind, fire, water — is not as overused as say Tolkien’s elves, but it definitely does crop up in the canon enough to be cliché.

Shinn takes this trope and creates an entire world based solely on the ability to control elements, i.e. the nobility is broken up into four factions, each with power over one element. The political struggles and problems that arise from various bloodlines being mixed and commoners that have the power results in an absorbing read.

Ahimsa Kerp, author of Empire of the Undead and Beneath the Mantle

Clichés go deeper than Prophesized Orphans aided by Wise Wizards squaring off against Dark Lords, but it’s surprising how many best-selling books use the basic formula of Wizards find small-town villagers (who may be hobbit like, orphans, or prophesized) and train them to defeat the Dark Lord. Terry Brooks, David Eddings, Dennis McKiernan and also Robert Jordan (his first book especially), follow this plot very closely. The Sword of Truth takes the farm boy recruited by a mad wizard and puts it first into S&M fantasies and then, somehow even worse, strange dreams of Libertarianism/Objectivism/Ayn Rand. There are a couple of notable standouts, though, that that take this cliché and transcend it.

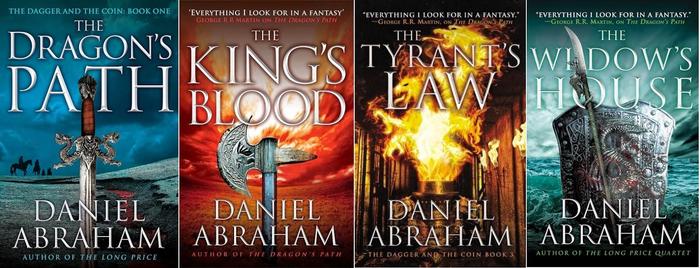

She’s not the chosen one in terms of a prophecy, but Cithrin bel Sarcour from Daniel Abraham’s The Dagger and the Coin series (The Dragon’s Path, The King’s Blood, etc.) is an orphan who becomes quite powerful. Abraham is the master of using tropes in unexpected ways. And Cithrin is a fascinating character who uses wiles, guile, cunning, sex appeal, and the power of drunken inspiration to stand toe-to-toe against the most powerful forces in the realm, going so far as to spurn the most powerful man in the world. Cithrin is an orphan written in a post-grim dark world.

China Mieville’s Un Lun Dun (2007) features a chosen twelve-year old girl named Zanna who is the product of an ancient prophecy to save the hidden city beneath the London we all know. However, about a third of the way through she falls to the enemy and it is up to her friend Deeba (hitherto seen as a sidekick) to descend back into the under city and face terrors including killer giraffes, binjas, and words themselves. This is a very effective way to subvert expectations, and thought it wouldn’t work for every book the protagonist change here is a good example of a new way to use chosen ones.

China Mieville’s Un Lun Dun (2007) features a chosen twelve-year old girl named Zanna who is the product of an ancient prophecy to save the hidden city beneath the London we all know. However, about a third of the way through she falls to the enemy and it is up to her friend Deeba (hitherto seen as a sidekick) to descend back into the under city and face terrors including killer giraffes, binjas, and words themselves. This is a very effective way to subvert expectations, and thought it wouldn’t work for every book the protagonist change here is a good example of a new way to use chosen ones.

Tad William’s Memory, Sorrow, and Thorn, the trilogy that inspired George R.R. Martin to try his hand at high fantasy, has the characters of good spending three long novels trying to figure out how to fulfill the prophecy. Only near the end do they realize that it is not their prophecy, but rather the antagonists’. This was another way to use prophecies with an interesting twist.

Gord Sellar, speculative fiction author, 2009 John W. Campbell Award finalist

In the past half-year or so I’ve just sort of discovered the brilliant Paul Meloy’s work, especially in the short stories collected in Islington Crocodiles (2008) and the follow-up novella Dogs with Their Eyes Shut (2013). It’s work that crosses countless genre and subgenre boundaries: it’s not exactly fantasy or horror or SF, just brilliant speculative fiction, and there are plenty of familiar fantasy tropes, if you look under the surface, but Meloy consistently does amazingly fresh, stunning things with them.

The nearest comparison I can think of is Lovecraft, complete with its own Dreamlands, and dark horrendous mechabiohorrific things that intrude from other realities, and “portals” (sort of) that characters occasionally pass through to do battle with evil beings, and bewildering pseudoreligious warfare based on a bizarre mythology… except it’s not at all Lovecraftian in terms of style. Meloy’s got his own, brilliant voice. Of all the books I’ll mention, Meloy’s deserves the most to be mentioned, as it’s the most startlingly new work here, and probably the least well-known outside the UK.

Also, I think a certain number of tropes have successfully been cross-pollinated to SF. For one thing, the landscape is littered with sentient weapons and suits of armor — Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice (2013), the mimints in Richard Morgan’s Takeshi Kovacs books, and, my favorite, the poor sentient space suit in Iain M. Banks’ “Descendant” (collected in The State of the Art, 1993)

Also, I think a certain number of tropes have successfully been cross-pollinated to SF. For one thing, the landscape is littered with sentient weapons and suits of armor — Ann Leckie’s Ancillary Justice (2013), the mimints in Richard Morgan’s Takeshi Kovacs books, and, my favorite, the poor sentient space suit in Iain M. Banks’ “Descendant” (collected in The State of the Art, 1993)

I don’t know if Black Gate readers would find that interesting, but I think the cross-pollination of fantasy tropes into SF has been interesting. (Also interesting is, at least from what I’ve seen, how little has gone in the other direction so far, though that’s starting to change, I think.)

Finally, I’m guessing William T. Vollman’s debut novel You Bright and Risen Angels (1987) isn’t on a lot of fantasy lists, but it is obviously “modern fantasy,” and is probably the most epic book I’ve seen from the late 20th century; it’s also a complete mess, but in a brilliantly catastrophic way. Basically, you have insects (and humans allied with insects) fighting the evil inventors of electricity, who vie for world domination; that’s it. It was written in a coffee-induced frenzy by a young homeless guy living in his cubicle at his crappy IT job, and it reads like that… in the best possible way.

Vollmann also wins for one-upping Flann O’Brien’s game: O’Brien begins At Swim-Two-Birds (1939) with the heading Chapter 1, but never gets to Chapter 2. Vollmann offers a table of contents extending far beyond the end of the book, outlining the future history of the battle for the world. It’s not just a comedic gag, though: it gives a context to the story, and an even more epic scale to an already epic book.

(And, really, At Swim-Two-Birds is probably worth a mention, old book though it is. I’ve never seen the “characters in a book wake up and come to life” done better or funnier than O’Brien did it.)

Garrett Calcaterra’s last post for us was “Can SF Save the World From Climate Change?“

[…] Calcaterra’s most recent posts for us were “Fantasy Clichés Done Right and “Can SF Save the World From Climate Change?” But in addition to all the […]

[…] Calcaterra’s most recent posts for us were “Fantasy Clichés Done Right and “Can SF Save the World From Climate Change?” In addition to investigative […]