The Suspension Bridges of Disbelief

A friend and I have been watching The Wheel of Time adaptation on Amazon. Both of us expressed surprise not at the open casting, which we agree is wonderful, but at how that production choice plays out in small hamlets like Rand al’Thor’s “home town” of Two Rivers. After observing that every possible racial group is represented in this isolated, insular mountain community, my friend had an epiphany.

A friend and I have been watching The Wheel of Time adaptation on Amazon. Both of us expressed surprise not at the open casting, which we agree is wonderful, but at how that production choice plays out in small hamlets like Rand al’Thor’s “home town” of Two Rivers. After observing that every possible racial group is represented in this isolated, insular mountain community, my friend had an epiphany.

“I had to remind myself,” said my friend, “that if I suspend disbelief to accept that there’s magic in this world, then I might also have to suspend my disbelief in genetics.”

But isn’t it curious, how difficult this can be? The addition of magic in the Robert Jordan universe does not imply the generalized suspension of basic science, but the casting choices made in populating the Two Rivers absolutely does. Surely, under normal conditions, a group of people who initially look very different and then happily intermingle and intermarry over several generations would soon produce a population exhibiting mostly blended rather than outlying traits?

So, if genetics is getting tossed out the window, what’s next? Photosynthesis? The electron constant? Algebra?

So, if genetics is getting tossed out the window, what’s next? Photosynthesis? The electron constant? Algebra?

I once had a housemate who professed a hatred of musicals, both on stage and on film. He explained that he simply couldn’t get around the idea that when people feel a ton of emotion, they break into song. I thought (but did not quite say) that that’s exactly when people are most likely to spontaneously burst into song.

Pro or con, musicals mark another instance where we either go along for the ride, suspending our disbelief when our heroes start warbling and trilling –– also when a brass band kicks in out of nowhere, playing (let’s say) “Seventy-Six Trombones”––or we cross our arms, huff and puff, and complain that musicals “aren’t realistic.”

Pro or con, musicals mark another instance where we either go along for the ride, suspending our disbelief when our heroes start warbling and trilling –– also when a brass band kicks in out of nowhere, playing (let’s say) “Seventy-Six Trombones”––or we cross our arms, huff and puff, and complain that musicals “aren’t realistic.”

But what is? Howard Shore’s exceptional score for The Lord of the Rings has nothing to do with realism. The Fellowship of the Ring is not accompanied on its journey by a traveling orchestra –– and if it were, wouldn’t we throw up our hands and declare the film to be entirely unbelievable?

The easiest stunt to pull off when requiring readers or viewers to freeze-frame their disbelief is to offer up only a single element that’s not of this world. Lorrie Moore does exactly this in I Am Homeless if This is Not My Home (winner of the 2023 National Book Critics Circle Award) by asking us to accept that her hero’s deceased ex-girlfriend might want to embark on one final post-mortem road trip, bantering like a boss all the way. Everything else (well, almost everything else) is essentially normal, right down to the tarmac, the songs on the radio, and said girlfriend’s steady rate of decay.

The easiest stunt to pull off when requiring readers or viewers to freeze-frame their disbelief is to offer up only a single element that’s not of this world. Lorrie Moore does exactly this in I Am Homeless if This is Not My Home (winner of the 2023 National Book Critics Circle Award) by asking us to accept that her hero’s deceased ex-girlfriend might want to embark on one final post-mortem road trip, bantering like a boss all the way. Everything else (well, almost everything else) is essentially normal, right down to the tarmac, the songs on the radio, and said girlfriend’s steady rate of decay.

Sometimes, one encounters a writer who appears to be sticking to the world as it is, but elements of dream or otherness are allowed to intrude, often with unpredictable results. The reader is themselves suspended, learning with every new-turned paged to be watchful, wary of what is real and what is not. Kathleen Jennings takes this approach in Flyaway, where disbelief is not so much suspended as it is actively cultivated. John Crowley’s Little, Big proceeds in much the same fashion.

Sometimes, one encounters a writer who appears to be sticking to the world as it is, but elements of dream or otherness are allowed to intrude, often with unpredictable results. The reader is themselves suspended, learning with every new-turned paged to be watchful, wary of what is real and what is not. Kathleen Jennings takes this approach in Flyaway, where disbelief is not so much suspended as it is actively cultivated. John Crowley’s Little, Big proceeds in much the same fashion.

But in general, suspension of disbelief works best in an additive sense. The story-teller allows for some new power, something that piggy-backs on the world already known. For example, in The Fifth Season, N.K. Jemisin allows for “orogenes” who control stone, a supernatural power built on what we already accept of geology and plate tectonics. Similarly, in Marvel Comics lore, the character known as Storm can control wind and weather –– but her powers depend explicitly on phenomena with which we are already familiar.

Even the finest works of the fantastic have their awkward moments. In HBO’s Game of Thrones, there’s a scene in which the Onion Knight, Ser Davos Seaworth, breaks young Gendry out of prison and sets him in a rowboat. When Gendry faces the wrong way, Ser Davos asks, “Have you ever been in a boat?” and Gendry answers, “No,” but the very next moment, he’s feathering the oars like a pro. All I can do is shake my head. Rowboats require practice: you’re facing the wrong way while steering, and each oar (long and heavy) functions independently. In the ocean, as Gendry is, every single wave impacts the oars differently. I’m forced to say that, as written, this charming, comic scene swan dives right over the cliff of believability. If poor Gendry has never rowed, all the royal blood in the world won’t help him. He’ll never get past the breakers, much less to the supposed safety of some far and distant shore.

Even the finest works of the fantastic have their awkward moments. In HBO’s Game of Thrones, there’s a scene in which the Onion Knight, Ser Davos Seaworth, breaks young Gendry out of prison and sets him in a rowboat. When Gendry faces the wrong way, Ser Davos asks, “Have you ever been in a boat?” and Gendry answers, “No,” but the very next moment, he’s feathering the oars like a pro. All I can do is shake my head. Rowboats require practice: you’re facing the wrong way while steering, and each oar (long and heavy) functions independently. In the ocean, as Gendry is, every single wave impacts the oars differently. I’m forced to say that, as written, this charming, comic scene swan dives right over the cliff of believability. If poor Gendry has never rowed, all the royal blood in the world won’t help him. He’ll never get past the breakers, much less to the supposed safety of some far and distant shore.

And yet, I’m perfectly happy to believe in three-eyed ravens and the faceless men of Bravos.

Perhaps the loftiest trick of all in the juggling game of disbelief is to remove some element that we have trouble imagining living without. Gravity, for example. The relative hardness and density of metal. Inertia. Strip away even one those three, and then try writing up a believable sword-fight. Good luck to ya’.

Perhaps the loftiest trick of all in the juggling game of disbelief is to remove some element that we have trouble imagining living without. Gravity, for example. The relative hardness and density of metal. Inertia. Strip away even one those three, and then try writing up a believable sword-fight. Good luck to ya’.

And this, perhaps, is why it is easier, when watching Amazon’s The Wheel of Time, to accept the One Power and way-gates and trollocs than it is to believe in a remote, mountainous outpost where the population covers just about every color of the human rainbow.

Magic, we buy (in part because it’s great fun to do so).

But reality?

Reality bites.

Onward.

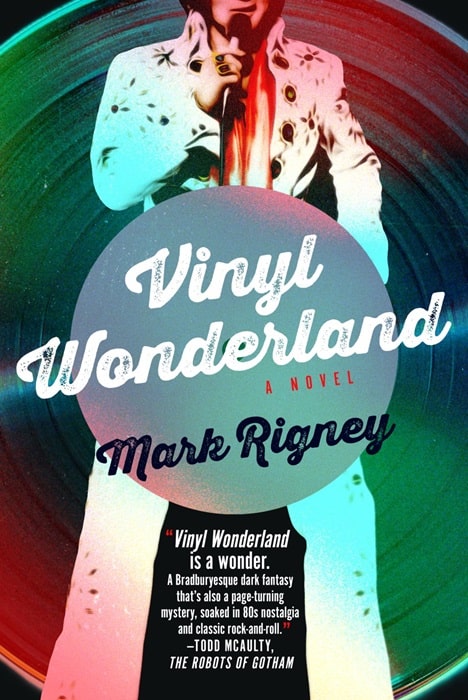

Mark Rigney is a writer and long-time Black Gate blogger. His work on this site includes original fiction and perennially popular posts like “Adventures in Spellcraft: Rope Trick.” His new novel, Vinyl Wonderland, dropped on June 25th, 2024. Reviewer Rich Horton said of Vinyl Wonderland, “I was brought to tears, tears I trusted. A lovely work.” His favorite review quote so far comes from Instagram: “Holy crap on a cracker, it’s so good.” A preview post can be found HERE, while his website lives over THERE.

wasn’t rand’s appearance supposed to be out of place in the village? it’d be one thing if he were just supposed to look like any random joe (and you add a throw away comment about how it’s a village of outcasts) then everything is fine.

My rule of thumb is good story first and everything far behind until I detect blatant sloppiness. Then I start drawing lines. If I’m invested in a story I’m pretty forgiving. This especially applies to TV which I refuse to ever take seriously.

Interesting to hear that you don’t find contemporary TV worthwhile. With shows like “Chernobyl,” “The Wire,” and “Black Mirror” available, among many others, I have moved firmly into the opposite camp.

It’s kind of like that “don’t be lukewarm” thing. To suspend disbelief in the reader/viewer, a story has to go so wildly and outrageously unrealistic that only one or two touchstones still anchor it to the comfort of experience, or a story has to confine unrealism to only one or two titillating differences. The moment a story goes between a quarter and three-quarters unrealistic, suspension of disbelief breaks. Story gets spat out.

Or, as you noted here, reality wrongly intrudes into unreality. I can’t enjoy “24” or “NCIS” because of those sorts of faux pas. “LandSat? You want to use LANDSAT for high-resolution ground surveillance?”

So disbelief has its own “uncanny valley”, then? Interesting thought!

Thanks for thinking so. The effect is most obvious in the cozy mystery, romance, and fantasy genres, in my experience, so it seems like it would be likely to hold true across most fiction. *Shrugs.* Perhaps not alternate-history fiction in the later volumes of a series, since those tend to rely on incrementing strangeness, and I guess they build up tolerance for disbelief.

Stanislaw Lem wrote a novel set on an alien planet where four or five human scientists arrive and try to figure out what’s going on, and they can’t. There’s not enough of a baseline. I wish I could remember what that book was called! Reality is just so damn unforgiving. Sorry, can I say “damn” on Black Gate? I need to read my employee handbook. Pretty sure I left it here someplace, but Black Gate’s Indiana Compound (underground, of course, with kobolds) is just so damn big. Oops. There I go again…

😆

Lem, Lem… if it was a funny story, it sounds like one of the pseudo-cautionary tales from “The Cyberiad,” but if it was not funny, it could be “Fiasco.” It has been a little bit since I read them, so not 100% sure.

Might want to check the watercloset for that handbook. Kobolds get funny notions about sanitation, sometimes.

Sounds like his most famous novel, “Solaris”, where the sentient planet tries to communicate with the human scientists but mostly sends them vivid, in-person nightmares.

I think that suspension of disbelief is a matter of training. If I read fantasy novels with dragons, I am trained to accept dragons in future fantasy novels. If no mixed populations appeared previously, then I fail to accept. And it depends on the context as well. Dragons cannot fly because physics, so fantasy not science fiction. But starships can fly faster than light in spite of physics, so science fiction. Makes the quest for waterproof definitions of genre so much more exciting!

I agree that the training is important, and for most, it begins VERY early. A great many picture books (not to mention board books) are fantasies. Children who are read to, or learn to love reading themselves, are bombarded with the fantastic. It’s only later, in middle school and high school, that the enforced diet tends to veer toward realism. (The life and times of Jay Gatsby, for example.) So I guess I’m saying that we are trained young, then untrained, and some of us never quite bend to the “mature” yoke of books that eschew the fantastic.

My problem with situations like you described regarding Wheel of Time’s village diversity, is that I immediately start thinking about the reasons why that village is so diverse (i.e. real world politics and hiring requirements) and it completely takes me out of the story.

If there were some other reason for those character’s appearance I would welcome it, but it’s never even implicitly addressed.

I rarely get so engrossed in a movie/TV series that I dig deeper into the “why is it?” kind of questions. Unless it is so counter to canon (and I know the canon). I’m there to enjoy the ride. Book series are a different matter.

I can’t comment on the wheel of time stuff, have avoided the books and the TV series simply because I can’t invest the time or chose to invest it elsewhere.

Suspension of disbelief, I reckon it all comes down to what one wants and how this aligns to others. RPGs are a classic here. What do you and the rest of the group want, super realistic that can get bogged down in rules, or extremely lightweight happy go lucky or whatever in between. The RPG world as well. ,Do you ignore the basics of genetics and say humans can hybredise with orcs and elves which opens the door to why not then a goat or a fruitbat or breakfast cereal, or do you say each species is genetically unique, or maybe somewhere in between where some sort of common ancestor exists. Actually been rewatchung a span of star trek tng and voyager recently and well we all know about what goes on there.

Started writing this with a point, um ah yes it comes down to personal taste and wants. It’s fiction so imagine it as you like and if you are lucky maybe others may see it the same way and you can have a rapport, but if they don’t, understand each imagines things in their own way and respect that, and be respected in return, live and let live, etc

Similar racial dynamics in Amazon’s other series, Rings of Power. I personally don’t mind at all, even though I notice that different racial characteristics show up within the same family even, I would love to live in a world where that was the norm. Because then it would stop being an means to exclude, disrespect, harm, and kill the other.

As well, I might have noticed the rowing skill blossoming in a person never having been in a boat, but maybe not, because I don’t do much rowing these days. Even used to row, as a member of a rowing club. It’s funny what we each notice to be lacking credulity, mostly based on our own experience. I think I’ve always wanted to be an open-minded person, so willing suspension is maybe easier? Don’t know, all I can say is it never occurred to me to compare a musical to real life. Let ’em sing and dance, I say, it could happen, maybe in Brigadoon, but in a universe of infinite possibilities, a disappearing village is as likely as breaking out in song and dance.

I’ll just mention that within 24 hours of this post appearing, the “The Wheel of Time” series got cancelled, and no season four will be forthcoming. I’m confident I had nothing to do with this (although butterflies flap their wings in Taiwan daily), especially because this post was really more about the suspension of disbelief in general––and no TV execs have the power to cancel that. Or so we hope.