Fantasia 2021, Part LI: When I Consume You

“Bed” is a 10-minute short film from Emily Bennett about a woman facing her fears. Our protagonist, Madeline, is alone in her apartment and we learn that she’s been hiding out there for some time. There’s something in her bedroom that scares her, something to do with her bed. We see that fear coming to a final confrontation, and a hint of what comes after. It’s an effective piece that tells a story tautly and well, and makes a single location visually interesting as it extracts different emotional tones out of the one place.

“Bed” is a 10-minute short film from Emily Bennett about a woman facing her fears. Our protagonist, Madeline, is alone in her apartment and we learn that she’s been hiding out there for some time. There’s something in her bedroom that scares her, something to do with her bed. We see that fear coming to a final confrontation, and a hint of what comes after. It’s an effective piece that tells a story tautly and well, and makes a single location visually interesting as it extracts different emotional tones out of the one place.

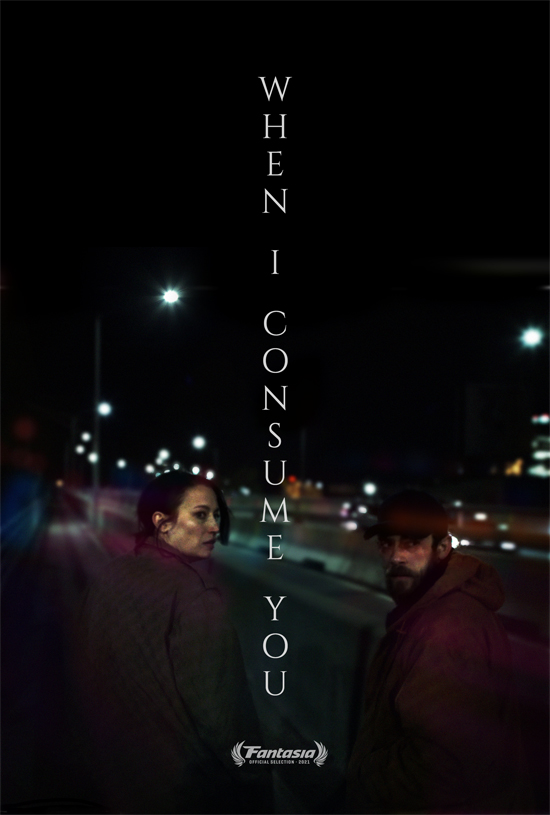

With it was bundled When I Consume You, a feature film written and directed by Perry Blackshear. In 2015 I reviewed and quite liked his first movie, They Look Like People, a humanistic and atmospheric story with elements of horror, about the emotional bonds between two people and how they’re tested. Which description fits When I Consume You as well.

It’s the story of Wilson Shaw and his sister Daphne, two people from a poor background struggling to get by in New York City; Wilson (Evan Dumouchel, who was also in They Look Like People) is a gentle man who’s had little luck in the job market, while Daphne (Libby Ewing) is an aggressive woman with a history of addiction who’s fiercely protective of her older brother. But someone or something from her dark past is after her. When it catches up with her it at least appears to be supernatural. Can Wilson toughen up enough to defeat a force Daphne cannot? Or is there a trick hidden in that question?

This is an excellent low-budget horror movie that keeps expanding its story in ways you don’t expect while at the same time using its lack of resources to keep a tight focus on its main characters. There’s nothing extraneous here, no locations that aren’t absolutely necessary; much of it takes place on the streets of Brooklyn at night, between graffiti-covered walls, in weed-filled parking lots. The urban landscape becomes the stage for Wilson’s training to fight evil, as though he were some medieval saint and the empty cityscape a desert filled with metaphysical potential. The cinematography’s moody, shadows everywhere except for oases of light where a bar’s open or the occasional streetlight works.

This is an excellent low-budget horror movie that keeps expanding its story in ways you don’t expect while at the same time using its lack of resources to keep a tight focus on its main characters. There’s nothing extraneous here, no locations that aren’t absolutely necessary; much of it takes place on the streets of Brooklyn at night, between graffiti-covered walls, in weed-filled parking lots. The urban landscape becomes the stage for Wilson’s training to fight evil, as though he were some medieval saint and the empty cityscape a desert filled with metaphysical potential. The cinematography’s moody, shadows everywhere except for oases of light where a bar’s open or the occasional streetlight works.

As Wilson fights for the souls of himself and his sister, it becomes clear that this is not a purely psychological story — this is not the story of somebody struggling only with inner demons. Supernatural evil is real and personal. That’s part of the point here, I think. Wilson’s struggling with real metaphysical concerns, and if that struggle is also symbolic the symbols gain strength from the objective reality of the battle.

But what is that struggle, and how do you fight it? Wilson wants to get tougher, like his sister, to fight the force threatening them. But while her toughness has let her keep the evil at bay for some time, it hasn’t let her defeat it. Is toughness enough, then? Or is Wilson’s quest misguided? What for me is most affecting about When I Consume You is that it considers these questions, about the utility of violence and the capacity to do damage to others, from more than a merely utilitarian aspect. If you gain a short-term advantage from violence, is there a long-term cost?

But what is that struggle, and how do you fight it? Wilson wants to get tougher, like his sister, to fight the force threatening them. But while her toughness has let her keep the evil at bay for some time, it hasn’t let her defeat it. Is toughness enough, then? Or is Wilson’s quest misguided? What for me is most affecting about When I Consume You is that it considers these questions, about the utility of violence and the capacity to do damage to others, from more than a merely utilitarian aspect. If you gain a short-term advantage from violence, is there a long-term cost?

It’s an old question that’s rarely dramatised well: does fighting even a clear evil make you evil? For a variety of reasons, popular culture in North America has tended to handwave that question, even dismissed it as a sign of weakness. Dramatically, it’s easy to follow a hero who struggles; easy for viewers to get pulled into a struggle and its outcome, and therefore difficult to tell a story in which the struggle’s itself a sign of failure. Blackshear’s figured out a way to make that approach work. When I Consume You is always effective as a story and a horror story, and also convincing in its approach to evil and what it means to be a fighter.

That’s impressive as well because horror tends to work by taking away agency from its lead characters. Usually a horror story has secondary characters falling away from the lead, betraying the main character or simply dying at the hands (or whatever) of the central monster. Wilson’s arc here is in some ways the opposite. He starts out isolated, except for his sister, and unable to fight. He doesn’t really try to overcome the isolation, but he does develop to become more capable rather than less. The question, of course, is whether that’s actually a form of giving in to the horror by learning to operate on its terms.

That’s impressive as well because horror tends to work by taking away agency from its lead characters. Usually a horror story has secondary characters falling away from the lead, betraying the main character or simply dying at the hands (or whatever) of the central monster. Wilson’s arc here is in some ways the opposite. He starts out isolated, except for his sister, and unable to fight. He doesn’t really try to overcome the isolation, but he does develop to become more capable rather than less. The question, of course, is whether that’s actually a form of giving in to the horror by learning to operate on its terms.

I don’t know that the movie’s necessarily pacifist any more than it’s necessarily anarchist, but there’s material here to be used to make an argument about the essential wrongness of violence and of power. There’s also an acceptance that a total and complete victory over evil is illusory. Which sounds abstract, but that’s the point of fiction: these abstract ideas are incarnated here in the story of a very real, credible character struggling with his life.

That we accept Wilson and Daphne as real comes through the excellent work of the performers (and also of MacLeod Andrews as a fast-talking antagonist). Dumouchel and Ewing are utterly convincing in their parts, not only as individuals but in the relationship they conjure between brother and sister: you get the sense of years of backstory through the way a word’s emphasised, the way a look’s exchanged. The sibling bonds between them are at the centre of the story, and because that works the film works. More than that: you see the different ways Daphne and Wilson approach the world, how she is cold and suspicious while he’s long-suffering and patient, and you realise how the story’s about the way he wants to gain some of her attitude at the same time as it takes apart why she is the way she is. And as it raises the question of whether, if he takes on her attitude, he can still feel the love for her that he does as the film opens.

That we accept Wilson and Daphne as real comes through the excellent work of the performers (and also of MacLeod Andrews as a fast-talking antagonist). Dumouchel and Ewing are utterly convincing in their parts, not only as individuals but in the relationship they conjure between brother and sister: you get the sense of years of backstory through the way a word’s emphasised, the way a look’s exchanged. The sibling bonds between them are at the centre of the story, and because that works the film works. More than that: you see the different ways Daphne and Wilson approach the world, how she is cold and suspicious while he’s long-suffering and patient, and you realise how the story’s about the way he wants to gain some of her attitude at the same time as it takes apart why she is the way she is. And as it raises the question of whether, if he takes on her attitude, he can still feel the love for her that he does as the film opens.

This sounds like a film with a lot on its mind, and it is, but what is really important here is the drama, the story. It’s a tale of a man who has to learn to fight supernatural evil, and what that might cost him. That tale’s told with an intense focus on its central character, and also a clever sense of structure. It’s intensely visual in an unusual way, using the unadorned reality of city streets as a backdrop for its story of a demonic force that is not mainly defined in occult or even religious terms — there’s some of that, but as that’s not Wilson’s focus it’s not the film’s either. The movie is instead deeply humanistic, not concerned with dogma but with the dignity of the mortal individual. It’s a tremendous accomplishment.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.