Fantasia 2021, Part XLIV: The Righteous

“Katu” is a 16-minute short from Sweden’s Oskar Johansson. It opens, as a title card tells us, five years after humanity lost its language. More precisely, after mysterious visitors took language from us; human beings can now only mutter syllables unintelligible to each other (in a nice touch, the nonsense words spoken onscreen are ‘translated’ by subtitles in an alien alphabet). In a large house a man and woman live. One night there is a knock at the door. They have a human visitor, and must struggle to find out what he wants before the alien language-thieves come. This is a moody piece, which feels like a part of a larger story. The glimpses of odd rites are difficult to parse, but the frustration of people not understanding each other is clear. Visually it’s dark and shadowy and effective, to the point that while I did not always understand the story I wanted to see more.

“Katu” is a 16-minute short from Sweden’s Oskar Johansson. It opens, as a title card tells us, five years after humanity lost its language. More precisely, after mysterious visitors took language from us; human beings can now only mutter syllables unintelligible to each other (in a nice touch, the nonsense words spoken onscreen are ‘translated’ by subtitles in an alien alphabet). In a large house a man and woman live. One night there is a knock at the door. They have a human visitor, and must struggle to find out what he wants before the alien language-thieves come. This is a moody piece, which feels like a part of a larger story. The glimpses of odd rites are difficult to parse, but the frustration of people not understanding each other is clear. Visually it’s dark and shadowy and effective, to the point that while I did not always understand the story I wanted to see more.

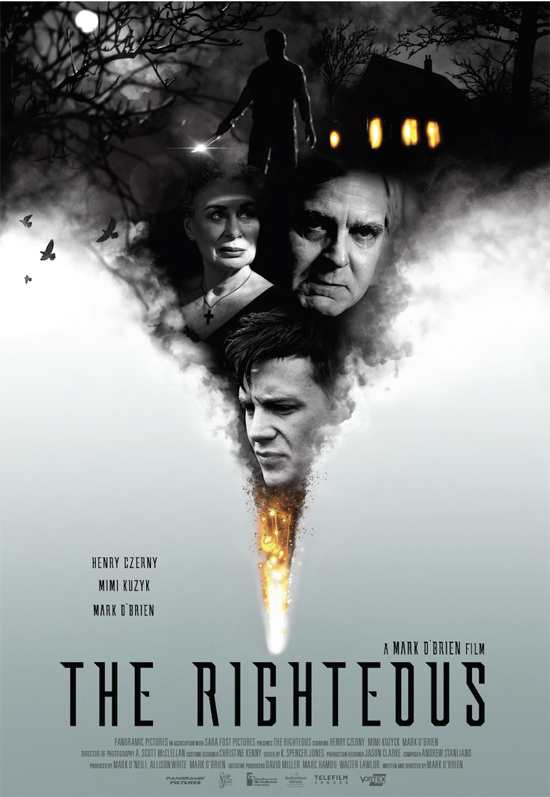

Bundled with it was The Righteous, one of the best feature films I’ve seen this year. Written and directed by Mark O’Brien, it stars Henry Czerny as Frederic Mason, an older man who years ago left the church to marry Ethel (Mimi Kuzyk). The movie mostly takes place around their rural home, when, in the aftermath of the death of their adopted daughter, a young man (O’Brien) stumbles from the woods with a damaged ankle. He becomes a long-term guest as he heals, but there’s a sinister aspect to him, and slowly the truth comes out — about him, and about Fredric.

This is a black-and-white horror movie, and it strikes you immediately with its visual power. The lighting and chiaroscuro effects are stunning, not only attractive and not only atmospheric but symbolic: illumination and shadow feel as though they represent spiritual realities. The promotional material for the film uses Bergman as a point of reference, which is clearly visible in the film’s emotional tone as well.

The movie’s generally very strong in its character work, and possibly the most notable aspect is its depictions of its lead character’s religious life. He has a relationship with God that is central to the film, and that relationship feels not just accurate but reasoned. That is, Fredric is an intelligent man, and his faith, while deep and emotional, comes across as something an intelligent and well-read man has thought about for much of his life. This is something that deeply informs the film, and by extension says something about his love for his wife, whom he chose above the priesthood.

The movie’s generally very strong in its character work, and possibly the most notable aspect is its depictions of its lead character’s religious life. He has a relationship with God that is central to the film, and that relationship feels not just accurate but reasoned. That is, Fredric is an intelligent man, and his faith, while deep and emotional, comes across as something an intelligent and well-read man has thought about for much of his life. This is something that deeply informs the film, and by extension says something about his love for his wife, whom he chose above the priesthood.

Now, while to me this is clearly a horror film, I mean that phrase very broadly — it’s not a conventional story, not something that ticks off a checklist of genre staples. It’s a movie that explores the emotional territory of horror, and explores the relationship of fear and sublimity: for not only in horror stories are sublimity, awe, and a sense of the divine all bound together. So the natural environment is present as in 18th-century gothics or 19th-century romantic writing, in this case not through scenes of mountain vistas but through the constant presence of deep forest to every hand — the power of the fearsome natural world is a source of the sublime. On the other hand, the house that is the story’s primary location is not a crumbling gothic mansion in which a sinister villain broods, being instead a home hallowed by a decades-long love that is visited by a mysterious and perhaps sinister stranger.

So there is horror here, and (conscious or not) traditions of horror stories that are used to get at some of the emotional terrain of horror stories. But there’s other stuff going on too. Fredric and Ethel have a relationship with the troubled biological mother of their daughter (Kate Corbett) which feels achingly true, marked by a kindness that humanises everyone involved. Fredric’s discussions with Graham (Nigel Bennett), a priest and friend, are powerful and intelligent; Fredric can ask him questions that, while logical in the moment, are standard horror-movie questions about sin, and the responses will be serious and thoughtful and credible and even moving.

So there is horror here, and (conscious or not) traditions of horror stories that are used to get at some of the emotional terrain of horror stories. But there’s other stuff going on too. Fredric and Ethel have a relationship with the troubled biological mother of their daughter (Kate Corbett) which feels achingly true, marked by a kindness that humanises everyone involved. Fredric’s discussions with Graham (Nigel Bennett), a priest and friend, are powerful and intelligent; Fredric can ask him questions that, while logical in the moment, are standard horror-movie questions about sin, and the responses will be serious and thoughtful and credible and even moving.

O’Brien wrote a taut script for this film. It’s filled with characters telling stories, and with recounted dreams. And yet it never feels self-indulgent, or as though the main story has paused to make room for something else. Everything fits with everything; everything adds up, and points in a single direction. The film’s based around a lot of talk between characters, but it’s never merely a series of talking heads, and if some of that is a function of powerful cinematography, much of it is because of the drama of the script.

Which itself is mainly from the perspective of Fredric. And for good reason; he is presented with a choice late in the movie, and it is this choice around which the story ultimately revolves. His grappling with sin and God therefore becomes the vital background which leads up to his choice, just as the things he did in his past set up the plot. If the movie’s concerned with the divine and the sublime, then, Fredric’s search for a meaningful relationship with God is something that comes out through an intensely dramatic structure, and through dramatic action involving violence.

But I wonder if the movie could not be seen another way. As a non-Christian I was struck by how it implies a reversal of the central Christian myth of self-sacrifice (with possibly a glance at the story of Abraham and Isaac as well). When we see a sacrifice made, particularly if we think in terms of human sacrifice, we assume that the sacrifice is unwilling — not just something or someone important given up by the one doing the sacrifice, but an act that would be resisted on the part of the sacrifice. What if that’s not true, and what if the one who makes the sacrifice is forced into the act? What if the thing being given up is not the tangible entity, but something more metaphysical?

But I wonder if the movie could not be seen another way. As a non-Christian I was struck by how it implies a reversal of the central Christian myth of self-sacrifice (with possibly a glance at the story of Abraham and Isaac as well). When we see a sacrifice made, particularly if we think in terms of human sacrifice, we assume that the sacrifice is unwilling — not just something or someone important given up by the one doing the sacrifice, but an act that would be resisted on the part of the sacrifice. What if that’s not true, and what if the one who makes the sacrifice is forced into the act? What if the thing being given up is not the tangible entity, but something more metaphysical?

And then again, what if the act has repercussions beyond the sacrificer and sacrifice? One of the things that often happens in horror movies is that the central drama of the main character hurts, scars, or kills other people. One person might gain something, but with terrible collateral damage. So it is here. In a movie that deals with the nature of the conscience, and how to deal with sin, it feels like a conscious point: you can struggle internally with memories of something bad that you did, but if you do not heal the actual damage the best you can, it’s liable to spread to hurt others and implicate you deeper in a web of pain of your own weaving.

Or so I see it. The movie to me is astonishing work because it inspires these kinds of thoughts, these deep considerations of good and bad and God and pain. But it does that because it’s a dramatically powerful tale whose surprising twists are in retrospect logical. And because the performances are powerful and nuanced, with a depth to match the depth of the script and the black-and-white imagery. The Righteous is a stunning film, and successfully wrestles with profound questions.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.