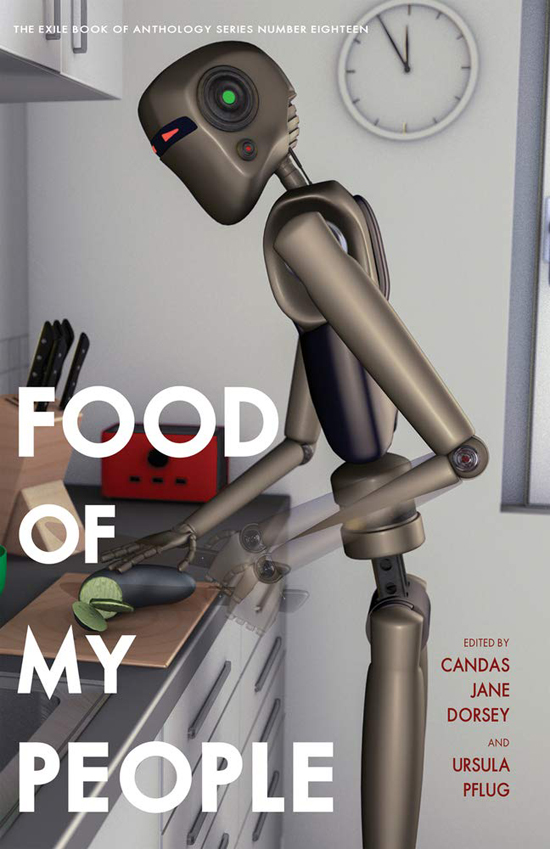

Food Of My People

Food, culture, and magic are deeply interlinked: geography and climate and trade routes determine ingredients, traditions transmit recipes, recipes are linked to folk beliefs, and ultimately the things we consume shape us. We are what we eat, and what we believe about the things we eat says something about us. Eating is a necessary act, and so there’s magic in it, varying with culture and ingredients.

Food, culture, and magic are deeply interlinked: geography and climate and trade routes determine ingredients, traditions transmit recipes, recipes are linked to folk beliefs, and ultimately the things we consume shape us. We are what we eat, and what we believe about the things we eat says something about us. Eating is a necessary act, and so there’s magic in it, varying with culture and ingredients.

Thus Food Of My People, a new anthology from Exile Editions co-edited by Candas Jane Dorsey and Ursula Pflug. Twenty-one stories, plus a twenty-second in Dorsey’s introduction, tell tales of food and the fantastic. There are tales reflecting a range of cultural traditions, though with a geographical focus on Canada (both editors and the publisher are Canadian). And each story is followed with a recipe, sometimes a practical usable one, sometimes a fantastical extension of the fiction.

Most of the stories are set in this world and this time, though a few take place in the future and a couple in fantastic secondary worlds. In Pflug’s Afterword, she points out that several of the stories can be described as New Weird, and if there is an overall genre tone to the book that’s probably it. The physicality of the subgenre aside, there’s something deeply weird about the process of eating, something about transformation at a deep level: ingredients into food, food into energy and shit, the whole process implausibly warding off hunger pains and sustaining life.

There are too many tales to discuss individually, and as with most anthologies, different readers will be drawn to different stories. For me, among the most notable were Casey June Wolf’s tale of family brutality “Eating Our Young,” Desirae May’s play with European fairy tales in “Red Like Cherries or Blood,” and Sang Kim’s concise meditation on grief and sea creatures in “Kracken.” Elisha May Rubacha conjures a detailed fictional world with food supply issues in “33 Raz Street.” Nathan Adler’s “Offerings” is an effective consideration of family and ghosts and horror stories.

Especially worth noting are the three stories that end the book. Sheung-King’s “You Are Eating An Orange. You Are Naked.” is a formally and stylistically challenging tale about lovers comparing mythologies, and since its writing has been extended into a widely-acclaimed full-length novel. Gord Grisenthwaite’s “SPAM Stew and the Marm Minimalist Bedroom Set from IKEA” captures the rhythms of oral storytelling in its yarn about the good things that come from SPAM and Tabasco sauce. And Geoffrey W. Cole’s “’Ti Pouce in Fergetitland” is a stunning closer to the book, a phantasmagoric brew of post-atomic language and folktale tropes.

It’s interesting to consider the overall effect of the book. For all the variety, indeed in part because of the variety, several distinct themes emerge. So does a kind of overall architecture.

The first half or so of the book has certain similarities. Most tales have a rural setting, typically in Canada (which does cover a lot of ground). There are a lot of young women narrators or point-of-view characters — counting Dorsey’s story in the introduction, seven of the first nine or ten tales, plus the second-person focus of Richard Van Camp’s narrative poem “Widow.” Not infrequently the younger women are dealing with a mother or older woman, but then family ties are a recurring focus throughout the book, along with initiatory knowledge passed down over generations. As the book goes on we see more cities, and stories from from a wider range of cultures, particularly Asian cultures. Voice becomes more varied, culminating in the distinct styles of the last three tales.

The range of different cultures — Indigenous, settler, and other — is notable because in each story we see the linkage of culture and food. And, often, a link to myth or traditional story. The concreteness of food becomes a way to embody the abstract idea of culture, and to embody the structure of a familiar story. You could argue that the food’s a kind of objective correlative for myth, a tangible symbol that gets across meaning. Or you could say that a recipe is a kind of story, with a fixed structure that produces something a little different every time you tell it. Then again, you could also say a recipe’s like a ritual, that (hopefully) ends with the miraculous production of something tasty and nutritious.

Or say this: the stories here use myth as an ingredient, but blend tastes to make a rich meal. Old tales find new settings, or are contrasted with other fictions. Sheung-King’s piece is perhaps the most obvious example of this fusion, but many of the stories have a kind of formal subtlety, balancing story with story or hiding a story (or speculative aspect to a story) within another.

Which is not to say that the stories or the book as a whole are merely analytical. In fact there’s some irony to the book’s cover image of a robot chopping a vegetable: you come away from the book with a sense of the messiness of food and life. You get a sense of the cycle of eating and being eaten, and how time makes food out of every cook.

The book reminds us that there’s a powerful link between story and food; the simple mention of food can call up whole stories. Six pomegranate seeds. Turkish delight. Cherry pie and a damn fine cup of coffee. Consider how much fiction begins or ends or prominently features great feasts: Mrs. Dalloway’s party, Trimalchio’s dinner in Satyricon, Bilbo’s birthday party, the celebration at the end of every Astérix album. Then again, in deference to the season, consider how many horror stories and monster-tales revolve around not just being killed but eaten, whether a discreet vampire bite or a sloppy zombie feast or being eaten from the inside out by an alien xenomorph embryo. But that’s the nature of food, frighteningly necessary: if you don’t have any, you have problems. Luckily, in addition to fine fiction Food Of My People has recipes, and so speaks to both flesh and spirit.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] Enjoy this great review from Black Gate: Adventures in Fantasy Literature […]