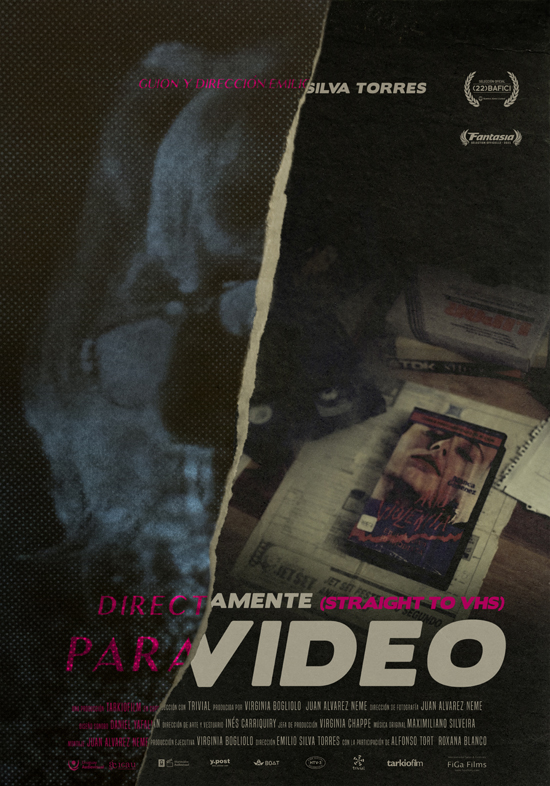

Fantasia 2021, Part XXIV: Act Of Violence In A Young Journalist and Straight To VHS

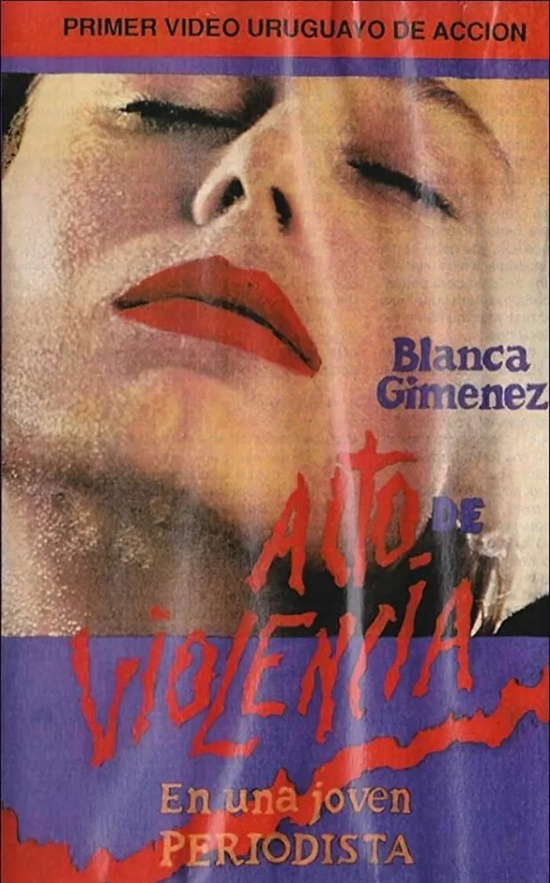

Straight to VHS (Directamente para Video) is a new documentary from Uruguay that investigates a video oddity from 1988. Act Of Violence In A Young Journalist (Acto de violencia en una joven periodista) is that oddity, an Uruguayan-made direct-to-video film from thirty-three years ago in which directing, writing, cinematography, soundtrack, and editing were all done by one man, Manuel Lamas. None of those things are done particularly well, but for some viewers the movie still has a strange power. The documentary looking at Lamas’ film comes to us from Emilio Silva Torres, and without claiming its subject is any good, it attempts to evoke the feel of looking at weird cinema of uncertain provenance without an internet to explain what you’re seeing. The Fantasia Film Festival bundled the two movies together, so I was able to see the thing itself and the investigation into its background back-to-back.

Straight to VHS (Directamente para Video) is a new documentary from Uruguay that investigates a video oddity from 1988. Act Of Violence In A Young Journalist (Acto de violencia en una joven periodista) is that oddity, an Uruguayan-made direct-to-video film from thirty-three years ago in which directing, writing, cinematography, soundtrack, and editing were all done by one man, Manuel Lamas. None of those things are done particularly well, but for some viewers the movie still has a strange power. The documentary looking at Lamas’ film comes to us from Emilio Silva Torres, and without claiming its subject is any good, it attempts to evoke the feel of looking at weird cinema of uncertain provenance without an internet to explain what you’re seeing. The Fantasia Film Festival bundled the two movies together, so I was able to see the thing itself and the investigation into its background back-to-back.

I started with Act of Violence, and I’m still unsure whether that was the best decision. It’s a movie about a woman journalist, Blanca (Blanca Gimenez), who is compiling a report on the causes of violence. Periodically the story of the film pauses for several minutes as she interviews people about the rise of violence in society; sometimes those people are psychologists from the health department and sometimes they’re soccer commentators. Much of the film is actually about Blanca’s personal life, though, particularly her relationship with Carlos, an Uruguayan businessman with ties to Canada. Except that by the time she meets him Blanca’s already given a piece of simple advice to a friend, which will turn out to have tragic and indeed violent consequences.

It’s certainly an odd film, and it is not good. It’s odd in a way I didn’t find especially engaging. Frankly, it’s pretty dull. Some of that is my fault, following from misplaced expectations; I had the idea that this was a slasher film, but the first act of violence comes at about the 70-minute mark. Then again, the trailer promises “Action … Romance … Mystery … Sex … Magic.” And there are moments of all these things, I suppose, but mainly it’s a story of romance between Blanca and Carlos, occasionally comedic and occasionally dramatic. Then a complication arises, in the form of the violence seeded early on and largely forgotten about, violence which also involves an amulet that might have some minor magical powers.

At first glance, then, this is a dull bad film. But it’s a bit more than that. It’s a very earnest movie, and has a kind of Ed Wood energy — there’s the sense that somebody cares about the material here, but has no idea how to craft a film. Basic rules of editing go out the window, scenes drag on formlessly, voice-overs come out of the blue. The investigation of violence is unsubtle, didactic, and oddly random. Plot and character are developed with a similar jerkiness. There’s an odd lack of atmosphere, even when the supernatural’s involved, so there becomes a kind of weird contrast between the banality of the story and the matter it tries to talk about — murder, lust, and magic.

At first glance, then, this is a dull bad film. But it’s a bit more than that. It’s a very earnest movie, and has a kind of Ed Wood energy — there’s the sense that somebody cares about the material here, but has no idea how to craft a film. Basic rules of editing go out the window, scenes drag on formlessly, voice-overs come out of the blue. The investigation of violence is unsubtle, didactic, and oddly random. Plot and character are developed with a similar jerkiness. There’s an odd lack of atmosphere, even when the supernatural’s involved, so there becomes a kind of weird contrast between the banality of the story and the matter it tries to talk about — murder, lust, and magic.

A lot of what is happening here is discussed ably enough in Straight to VHS. The documentary’s effectively a first-person account of how Emilio Silva Torres got interested in Act Of Violence, and his quest to find out more about the film and its background. We hear from him and other Uruguayan cinéastes who’ve watched Lamas’ film about its importance, then see Silva Torres try to track down people involved with the movie. Which turns out to be difficult: the few people he’s able to find don’t want to speak to him on camera. Slowly, though, a portrait comes out, and with it a portrait of Lamas as a person.

The documentary’s held together by Silva Torres himself; interviews and clips fit into his story of pursuing Lamas. Straight To VHS ends up becoming about more than just one film, though. Silva Torres gets across the weirdness of Act Of Violence by inserting little fictions into his documentary, along with bits of business that be fictional or might not. A mysterious package. The sudden discovery of a house that was a location in Act Of Violence, minutes away from where he lives.

The documentary’s held together by Silva Torres himself; interviews and clips fit into his story of pursuing Lamas. Straight To VHS ends up becoming about more than just one film, though. Silva Torres gets across the weirdness of Act Of Violence by inserting little fictions into his documentary, along with bits of business that be fictional or might not. A mysterious package. The sudden discovery of a house that was a location in Act Of Violence, minutes away from where he lives.

This is an interesting approach, and at times risks feeling excessive — how much of the documentary can you take seriously when the director’s undermining the pretence of objectivity? But then, that’s perhaps the point: what is objectivity, and where can you find it? Straight To VHS was made because a guy was obsessed with a movie made by a guy who was obsessed. That’s not a recipe for solid objective certainty.

Then again, Silva Torres at least has a community around him to help ground him and his story. His interviews with other fans of the film don’t just help establish the nature of the movie and why people in Uruguay grew fascinated by it (Act Of Violence was not a film that travelled much outside of its home country). They bring out something of the experience of watching the film as a collective — we hear memories of New Year’s Eve parties marked by watching a copy, for example. Cinema, at least up until the age of COVID, has often been considered to have a special power and perhaps to be its truest self when there’s a crowd for an audience: a theatre full of people, or at least a room full of people. As technology’s developed and the home experience has become more common that’s come to be said less, but Silva Torres brings back the feel of an underground phenomenon — the sense, when you’ve seen a weird film, of being part of a secret conspiracy. The cult feeling that you get from a cult classic.

Then again, Silva Torres at least has a community around him to help ground him and his story. His interviews with other fans of the film don’t just help establish the nature of the movie and why people in Uruguay grew fascinated by it (Act Of Violence was not a film that travelled much outside of its home country). They bring out something of the experience of watching the film as a collective — we hear memories of New Year’s Eve parties marked by watching a copy, for example. Cinema, at least up until the age of COVID, has often been considered to have a special power and perhaps to be its truest self when there’s a crowd for an audience: a theatre full of people, or at least a room full of people. As technology’s developed and the home experience has become more common that’s come to be said less, but Silva Torres brings back the feel of an underground phenomenon — the sense, when you’ve seen a weird film, of being part of a secret conspiracy. The cult feeling that you get from a cult classic.

I’ve mentioned before in these reviews that there’s a specific kind of emptiness you had before the internet, a lack of context when you encountered something new. You could not then hop online and learn everything there was to know about a movie, could not find other people reacting to the same thing you’d just seen. Maybe you could talk about it with friends; maybe you could guess at connections or backgrounds. But you never really knew. Beginning with Silva Torres discovering the film years ago, Straight To VHS gives us that feeling, and we see how that blankness, that feeling of mystery, slowly gave way as the internet became widespread. Over the early years of the 21st century Silva Torres and his friends find out more and more about Act Of Violence. An actor surfaces; then another. Old hands in the Uruguayan film industry talk about their memories of Lamas.

It raises a bigger question, one of the questions I think the documentary’s about beyond just the one film. And that is the question of what we really want to know about a film that moves us. What is it we hope to learn from a documentary? What is it that drives somebody to learn where a movie came from? Is that even possible? If you learn about the director and the actors and their relationships and what the director wanted to do and the director’s history in film … does any of that help you understand the films the director makes? Or does it all get in the way?

It raises a bigger question, one of the questions I think the documentary’s about beyond just the one film. And that is the question of what we really want to know about a film that moves us. What is it we hope to learn from a documentary? What is it that drives somebody to learn where a movie came from? Is that even possible? If you learn about the director and the actors and their relationships and what the director wanted to do and the director’s history in film … does any of that help you understand the films the director makes? Or does it all get in the way?

There is a weird honesty to what Silva Torres does here. It’s as though he’s challenging himself. How far can he go into learning about Lamas, and how far does he want to go? What, really, is the point? The strange quasi-fictional elements bring this out: they hint at greater mysteries and questions, creating an unreal sense that leads us to doubt everything we see. (Was Lamas hiding a secret? Why do people not want to talk about him? Was there ever really a movie from 1988 called Act of Violence In A Young Journalist? Did people ever actually watch movies recorded on magnetic tape? Is there really a country named Uruguay?) But the main question has to be: what’s the point? Or to put it another way: what is there to really know about the film and about Manuel Lamas that is worth knowing and is not communicated by the film itself?

The technique may be self-conscious, but it works in that it raises these questions without being explicit about them. The documentary has some value because the film has value, to some viewers at least. But why do we want to know about the things that moved us, rather than be content with being moved? More precisely: why do we think there’s a hidden truth to be uncovered, or some deeper insight to be gleaned?

The technique may be self-conscious, but it works in that it raises these questions without being explicit about them. The documentary has some value because the film has value, to some viewers at least. But why do we want to know about the things that moved us, rather than be content with being moved? More precisely: why do we think there’s a hidden truth to be uncovered, or some deeper insight to be gleaned?

As I say, I watched Act Of Violence before Straight To VHS, and the downside of doing that was seeing a bad movie without having been prepared for it and without commentary from fans of the thing to let me know what to look for. The upside is that I saw it unspoiled, and had the experience of watching the movie without context, the way viewers would have done in 1988. I don’t recommend the film to viewers on its own, except to people who like psychotronic movies. But the documentary’s worth watching for anyone, whether they’ve seen its subject or not; arguably, it’s better to watch the documentary alone, and leave Act Of Violence as an unseen legend, haunting the mind with its promise of the weird and the unknowable. For me, the documentary does a better job evoking that tone than the fiction.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Some really insightful stuff here, Matthew (although I’m not sure I ever want to watch either movie!)