Up and Down Again: Robert Silverberg’s Up the Line

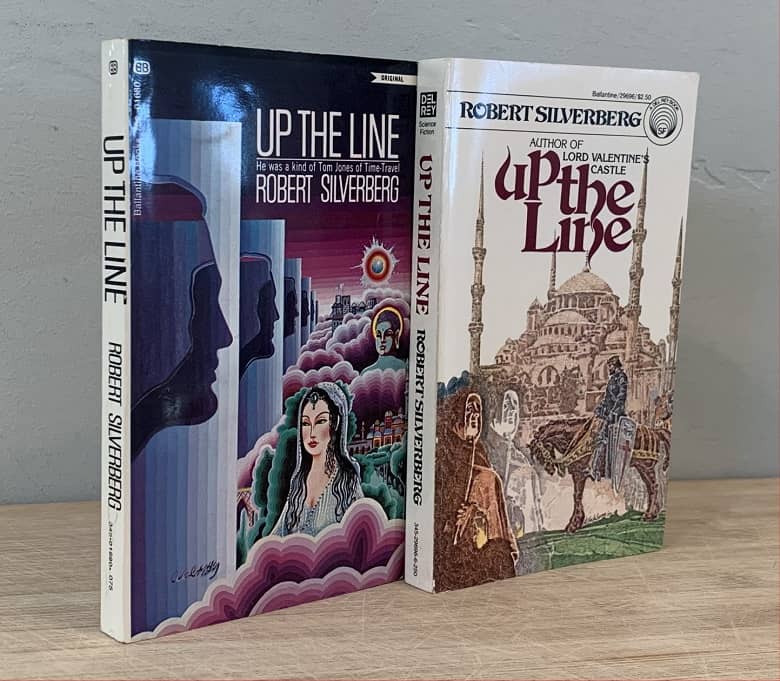

Up the Line by Robert Silverberg

First Edition: Ballantine, August 1969. Cover art Ron Walotsky.

Also shown: Fourth printing, June 1981. Cover art Murray Tinkelman.

Up the Line

by Robert Silverberg

Ballantine (250 pages, $0.75, Paperback, August 1969)

Cover art Ron Walotsky

Having discussed Isaac Asimov’s The End of Eternity last time, I thought to move forward a decade or so and look back at a similarly recomplicated tale of time travel and time paradoxes: Robert Silverberg’s 1969 novel Up the Line.

Silverberg has written numerous novels and stories concerning time travel (there are photos of some of them lower down on this page), but there are different kinds of time travel stories, and Silverberg has focused on only a couple. Some involve simple trips into the future (Wells’ The Time Machine) or past (Silverberg’s own “Hawksbill Station”) with or without return tickets; others involve interfering in history and creating, inadvertently or intentionally, alternate timelines; others involve preventing such alternate timelines; and so on. Of Silverberg’s time travel stories, Up the Line is an example of the most complex type, about the potential paradoxes inherent in time travel, how to avoid them or deal with them. And so it’s his one novel most directly comparable to Asimov’s The End of Eternity.

The book was published as a paperback original by Ballantine Books, during Silverberg’s prolific middle period, in 1969. So far as I can tell, it has never been reprinted on its own in hardcover. (Per isfdb, it’s included in a 2003 Book Club omnibus with three other novels, and a 2011 Subterranean press omnibus with two other different novels, both of these omnibuses hardcovers. The most recent individual reprint of this novel is an ibooks trade paperback in 2002. None of these three volumes are available in new condition except at exorbitant prices.) So page references here are to the original Ballantine edition, last reprinted in 1988.

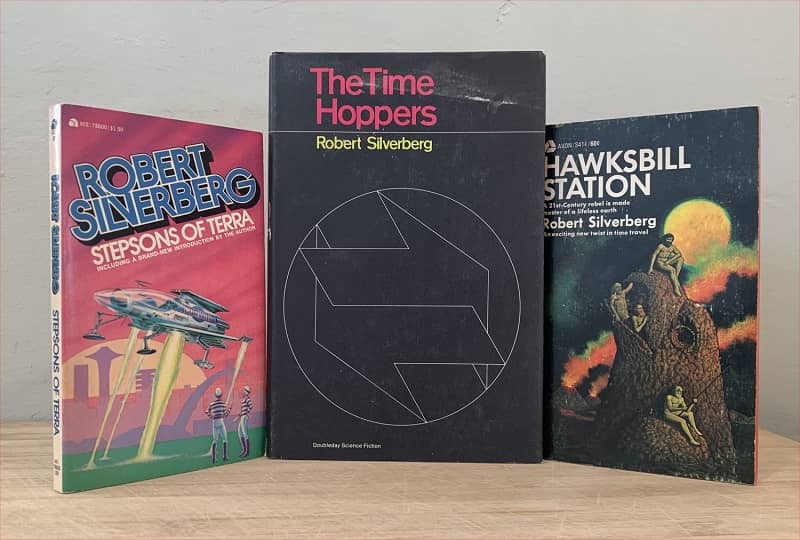

Earlier Silverberg time travel novels:

Stepsons of Terra, Ace Books, 1958; 1977 edition shown here, cover by Don Punchantz

The Time Hoppers, Doubleday, 1967; Book Club edition shown

Hawksbill Station, Doubleday, 1968; 1970 Avon edition shown, cover by Don Punchantz

Gist

A young man working as Time Courier from a sexually libertine 2059, escorting tourists into the past to witness famous events in the history of Byzantium, falls passionately in love his own great-great-multi-great grandmother, then pursues a renegade tourist who sets off a series of cascading paradoxes that threaten the courier’s very existence.

Take

This is an over-the-top time travel novel that playfully riffs on famous time travel paradoxes, revels in the sexually permissive era of science fiction in the late 1960s, and heavily indulges in the author’s fascination for ancient Byzantine history. It’s fun.

Summary and [[ Comments ]]

This is a medium-length book of 250 pages with 63 chapters, so I’ll summarize major plot developments and speculative concepts, rather than account for every single chapter. Furthermore, I’ll insert some headings to break the novel into its broad plot acts.

Setup, and Education

- The first chapter, over two pages, has the narrator recalling how Sam the guru invited him to “ride the time-winds,” and how he still lusts after Pulcheria, his now-lost “great-great-multi-great-grandmother.”

- We flash back to when the first-person narrator is Jud Elliott, a 24-year-old man, aimless and dissolute, arrives in New Orleans, having quit his job as an assistant attorney in Newer York. He hooks up with two women, Helen and Betsy, who take him to their apartment where they live with Sam the guru, a very black man, and they all have sex and smoke weed.

- Jud is surprised to learn that Sam is a Time Serviceman, since Time Servicemen have this reputation for being stolid and upright and dull. Sensing Jud’s lack of purpose, Sam asks about his heart’s desire. As it happens, Jud is fascinated by Byzantine history, having taken five trips to Istanbul (in the present). Sam persuades Jud to apply to the service.

- Jud applies, fills out an application and undergoes an interview. He’s given a truss to wear around his waist under his clothes, a “timer” with buttons and dials to send him through time, with a range limited to 7000 years.

- Jud is sent on a trial run with Sam. They go back a couple weeks so that Jud can see himself arriving in New Orleans, and the orgy that ensued; then make quick stops in 1961, 1858, and so on all the way back to 5800 B.P. (before present). Returning to the present in 2059, Sam vouches for him: Jud is hired.

- Jud takes classes. His instructor, Dajani, explains about the various paradoxes the students need to watch out for.

Theory of Time Travel

In this book Silverberg develops a theory of time travel that is implicit in earlier stories and novels by other authors but not, so far as I know, developed in quite this detail. Taking a break from the plot summary, here are some details of that theory gathered in one place:

Context

- Time travel has existed, in 2059, for only a couple decades, since the discovery of the “Benchley effect” that enables it.

- The Time Service consists of two parts: Time Couriers, who escort paying customers into the past to witness famous incidents (with a customer preference for assassinations); and the Time Patrolman, who prevent or repair abuses of time travel by the couriers and their clients. “Up the line” means going further back into the past.

Rules and Limitations

- A time traveler can’t materialize in space already occupied by something else; an automatic buffer kicks in, and the traveler returns to his starting point. (page 21.7) (Of course, this begs the question of whether air occupies space.)

- Patrolmen aren’t allowed to profit from their travels, e.g. by selling artifacts. (p25.4) (But patrolmen do get away with collecting artifacts for their personal possession, as Sam does.)

- You can’t get to your own future (p31).

- Travel in time doesn’t include spatial travel. Thus to travel to ancient Byzantium, Jud must leave from modern-day Istanbul. (Another quibble: but the Earth moves through space…)

- You can’t make “good” changes either. History must be preserved.

- On the other hand, tiny changes, like stepping on ant, can accumulate and eventually, perhaps, lead to unanticipated changes in history – which might result, for example, in a person popping out of existence. (This foreshadows the novel’s end.)

Paradoxes

- What is the risk of changing the past by killing, say, Mohammed? Is there a Law of Conservation of history, a student asks? Maybe, but the Time Service doesn’t’ want to risk it. Thus the Patrolmen. The student isn’t satisfied with this answer.

- The Paradox of Temporal Accumulation. Couriers take clients to historical events, often visiting the same ones repeatedly. Yet each time a courier arrives at a particular event, he sees only versions of himself, (with their tourist groups) in his particular past – not all the theoretically infinite number of couriers and tourist groups who will arrive there from his future.

- The Paradox of Discontinuity. This is when you see a fellow courier in the past who doesn’t recognize you. That’s because you’re seeing a version of your friend from an earlier uptime before he’s met you! Jud isn’t too quick to understand this.

- The Paradox of Duplication. This is when two versions of the same person exist at the same time. Couriers are told to avoid this at all costs, and must carefully time their comings and goings to avoid it. (But if it happens, it can be remedied by going “up the line” to prevent the duplicate from making his trip, in effect wiping out a small piece of history.)

- The Paradox of Transit Displacement. This is when the time traveler realizes that everyone around him has a different memory of the past than he does. This is because some change has been made to history, and must be fixed, should the traveler return to his present and cease to exist.

Allusions:

- Silverberg was obviously familiar with the history of science fiction stories about time travel and its paradoxes, and there are a few places where he seems to tip his hat in those directions.

- The notion of killing Muhammed invokes Alfred Bester’s 1958 story “The Men Who Murdered Mohammed.”

- The name of another courier, Madison Jefferson Monroe, has the ring of a stolid, patriotic, Heinlein character, perhaps in tribute to Heinlein’s two famous stories of time travel recomplication, 1941’s “By His Bootstraps” and 1959’s “All You Zombies.”

- The notion of changing history by stepping on an ant recalls, of course, Ray Bradbury’s famous story about stepping on a butterfly: 1952’s “A Sound of Thunder”.

- And of course the idea of bedding one’s ancestor, or becoming (even if accidentally) one’s own ancestor, expands on those same two Heinlein stories (which also inspired David Gerrold’s 1973 The Man Who Folded Himself).

- The notion of compound interest over centuries has been used many times, perhaps earliest in the opening pages of Wells’ The Time Machine, and there was a Mack Reynolds story about it. Silverberg used a variation of the idea in his 1972 short story “What We Learned from This Morning’s Newspaper.”

Back to Our Story

- Jud takes classes. Paradoxes aside, the couriers are instructed to avoid muddles in the past – e.g. being noticed by the locals — by speaking as little as possible when there, by letting the courier handle all the expenses, and so on. Yet it doesn’t matter if couriers “play around” with the locals, as long as they take their monthly pill (to suppress fertility).

Courier Trip to New Orleans

- Jud and another courier take a tourist group to New Orleans, 1935, to witness the assassination of Huey Long. In 1935 they’re amazed by above-ground power lines, by how ugly people are, how tame a strip tease is. Unused to alcohol, the couriers and travelers from 2059 are advised to limit themselves to one drink a day. Or learn how to drink. [[ Weed and other recreational drugs have apparently supplanted alcohol in 2059. ]]

- Something of an aside: At a party in his honor, Jud meets Emily, a “splitter”, i.e. a gene editor, who predicts that the current generation will be the last one of “normal” people. We heard about some of this in the early chapters when introduced to Sam the guru, whose ancestral line had been edited to return it to its origins, as part of the “Afro Revival” (recall Silverberg is writing in 1969).

Settling in Istanbul for Trips to Constantinople

- Training complete, Jud travels to Istanbul, and undergoes some hypnosleep training in the language. [[ This notion of learning by hypnotism, or hypnosleep, was common in 1950s and ‘60s sf (I recall examples from Heinlein and Clarke), but obviously hasn’t panned out. ]]

- He pairs with another courier, Capistrano, to take eight tourists into the past. From the Hagia Sophia, they jump first to AD 408, when the Turkish influence from earlier in history had vanished.

- [[ Silverberg was sophisticated enough to understand that homosexuals were common everyplace and everytime, even if his take on them was cliched. Jud’s party of eight includes “a pair of pretty young men from London” and when Jud returns later to their common room at the inn, “the two pretty boys from London looked sweaty and tousled after some busy buggery.” It was still only 1969. ]]

- He and Capistrano move to AD 532 and later times, and after two weeks return home. During the trip Capistrano reveals an odd fantasy: to kill one of his ancestors, as a way to commit suicide.

- Obliged to take a two-week “layoff” after each trip, Jud does some private shunting across centuries of Istanbul, and at one stop sees his old friend Sam – but encounters the Paradox of Discontinuity (see above); the Sam he meets denies knowing him.

- Jud then meets chief courier Themistoklis Metaxas, one of the original couriers. The first thing Metaxas says to Jud is “You haven’t lived until you’ve laid one of your own ancestors.”

- He and Metaxas take a group of tourists to AD 532, to witness riots that burn the city down. Metaxas seemingly knows everyone and has slept with all the women across Constantinople history; he offers to hook up Jud with the current Empress. Jud hesitates and declines, for now.

- Metaxas invites Jud to his villa in 1105, his home away from home in 2059, chosen because his presence there, even on a vast estate over decades, will have no effect on history. Metaxas has compiled a book of all his ancestors, with plans to seduce all the women—except for his own mother of course.

Jud Becomes Obsessed with Ancestor Pulcheria

- Time passes and Jud gains confidence as a courier. During one layoff he travels to Athens and begins exploring his own family tree, meeting his grandparents as young adults, and even his own mother as a naked little girl. He compiles details about his Ducas family history.

- Jud visits Metaxas in 1105 and meets Metaxas’ gggg-grandmother. A scholar staying on the estate explains how he is recovering lost Greek plays, planning to take them to the present and plant somewhere where they’ll be found by archaeologists. (Strictly speaking, against regs, but harmless enough, he claims.)

- Jud shows Metaxas his family tree, and Metaxas recognizes some of the names, including the beautiful 17-year-old Pulcheria. Wouldn’t Jud like to meet her? Again Jud hesitates; but we’ve known about Jud’s obsession with Pulcheria since the first page of the novel; it frames the entire book.

- On his next tourist run he encounters two paradoxes. One of his tourists, a Marge Hefferin, somehow besotted to a crusader named Bohemond who she is now seeing in person, runs to him as he passes, ripping open her tunic, offering herself to him. She’s quickly cut down by Bohemond’s retinue. Jud (rather than contacting the Patrolmen, whose job it is to clean up such infractions), shunts a couple minutes down the line and restrains her — meaning that for a couple minutes, there are two Juds at the same place. Then returns to where he left from.

- During that night he jumps to see Metaxas in 1105, and encounters Pulcheria Ducas in town. He’s instantly in lust. But he’s afraid to meet her, considering the several ways he might be discovered and punished.

- He signs up, as a tourist, to a Black Death tour. The tourists see victims at all stages of the plague. And corpses. Flagellants. Their courier dispassionately describes the history of the plague.

- Jud takes up Metaxas’ offer to bed the Empress, despite her vile reputation. He has to qualify. He undergoes her orders for four hours. At the end, Jud thinks, “when you’ve jazzed one snatch you’ve jazzed them all.”

Paradox Crisis Ensues

- Jud leads a two-week tour, though he’s lost his enthusiasm. He’s preoccupied by Pulcheria. He puts up with a coarse tourist named Sauerabend, who’s into little girls. (Stated matter-of-factly.) Capistrano visits, old and tired, claiming he’s finally done it – killed one of his ancestors. He jumps away, to become a nonperson. But a Time Patrolman appears, then leaves to take care of him. Later Jud learns that Capistrano stayed in the past and had a family, until the Patrol caught up with him and wiped him out anyway.

- Jud shunts to 1105, where Metaxas arranges for him to meet Pulcheria, at a soiree of her husband’s. Jud pretends to be a nephew of Metaxas. She is smitten by him too, and they meet in a small room just before dawn, Jud’s culmination of a dream. Afterwards, she senses a strangeness about him; she promises to see him again, and she hopes he can give her a child (which of course Jud is forbidden to do).

- When Jud returns to his tourist party (after only 3 minutes, despite the hours or days he spent in 1105), one of them, Sauerabend, is missing; he must have jumped away, by hacking his timebelt, during the three minutes Jud was gone. Jud soon becomes panicked. As he did to correct the Marge incident, Jud tries jumping back just a few minutes to intercept Sauerabend before he leaves. But he misses; he tries again; and the result is that Jud creates two contemporaneous versions of himself. A huge paradox problem

- Much recomplication ensues. Sauerabend has disappeared, but to when? Other couriers arrive, in support of one of their own, and set about searching eras of the city across time for any signs of him.

- After helping with the search himself, Jud takes a break to return to 1105 and see Pulcheria again. But when he arrives in 1105, no one at Metaxas’ estate knows of any Pulcheria! Yet Jud discovers her as the wife of the local innkeeper. It’s a Transit Displacement Paradox.

- One of the couriers, Jud’s old friend Sam, finds Sauerabend. He had stayed in 1105, and became the very innkeeper where Jud found Pulcheria. Pulcheria became his wife (!), after an incident on the street when he molested her as a girl and her family disowned her.

- And so the couriers stage an intervention to prevent the street incident, replace Sauerabend’s hacked timebelt with a proper one, and return him to 2059 for prosecution.

- Meanwhile, Jud is concerned with what to do with himself and his duplicate. Perhaps they can establish an estate somewhere back time and share it, and share their roles as couriers?

- But Sam appears to warn him the Time Patrol is after him. It was the differing serial numbers on Sauerabend’s two timebelts that gave him away.

Paradox Crisis Resolved

- So Jud flees to 3060 BP, to become a god to the local farmers, who give him all the women he wants. Sam and Metaxas visit him occasionally to bring supplies. But he misses Pulchiera. Meanwhile he’ll write his memoirs. He knows the Patrol can find him and wipe him out; but they’re waiting to prosecute the original Jud up in 2059. He knows it will happen eventually, even in the middle of—

And the book ends in the middle of a sentence.

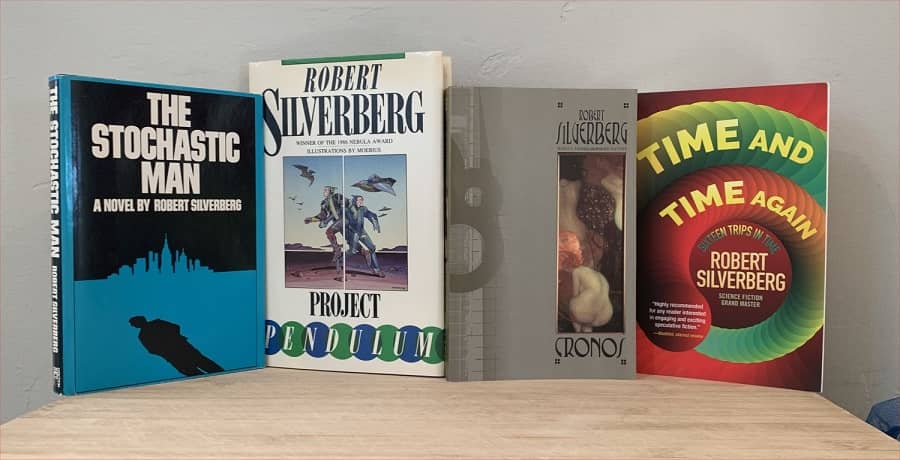

Later Silverberg time travel works:

The Stochastic Man, Harper & Row, 1975

Project Pendulum, Walker/Milleennium, 1987, cover by Moebius

Cronos, ibooks, 2001, cover by Gustav Klimt (omnibus of three novellas)

Time and Time Again, Three Rooms Press, 2018 (collection of 16 stories)

Comments

This is a novel that at once thinks seriously about the paradoxes inherent in time travel, and at the same has a lot of fun with it. Silverberg knows that his rules and paradoxes don’t rigorously hang together (and has an instructor virtually admit it), but then do anyone’s? I suspect Silverberg wrote the book as a playful response to a science fictional tradition, that of time travel paradoxes, and to indulge himself on two counts.

First, he took the occasion to write a jolly, bawdy novel that would have been impossible to publish only a few years before. (At the same time, as bawdy as the novel is, now that I think about it I don’t think it ever uses the f-word.)

Second, Silverberg, still writing substantial nonfiction books on historical themes into the early 1970s, took the opportunity in this novel to rhapsodize about Byzantine history, no doubt writing from first-hand experience in his travels. That there are a few too many such passages is my only real quibble with the book.

So, no deep truths here about the implications of time travel on the nature of reality. Or implications on how the use of time travel would affect the future of humanity, as Asimov’s book suggested. Or even deep thoughts about the nature of history. It’s playful, it’s edgy for its time, and it’s fun.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was of Isaac Asimov’s The End of Eternity. Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive, which has this index of Black Gate reviews posted so far.

In the time-travel field, did you watch the show, Timeless? I thought it was very good, and they got to wrap up all the story lines.

It made up the second half of this BG post (following the MASSIVE disappointment of Dirk Gently).

https://www.blackgate.com/the-public-life-of-sherlock-holmes-dirk-gently-is-not-timeless/

– if all of Silverberg’s covers had all looked like those I never would have read him, thankfully Jim Burns covers came along.