The Place of Fantasy in Science Fiction: Dell Science Fiction Reviews

|

|

My main apprehension in agreeing with John O’Neill to write regular reviews for Dell Magazines appears to have been realized. This bi-month, for stories published in these issues in particular, I don’t have much — if anything — to say. In regards to the overall discourse, however, I have a few thoughts, and those thoughts might drive this article out of the bounds of a “review” into that of an “essay.”

So here it is: a number of the stories put me in mind of the sometimes-adversarial relationship between the science fiction and fantasy genres.

This time around, my rumination on this topic might have begun with Norman Spinrad’s review of books for the final 2019 issue of Asimov’s. Spinrad has little sympathy for fantasy, particularly when it — in his view — masquerades itself as science fiction.

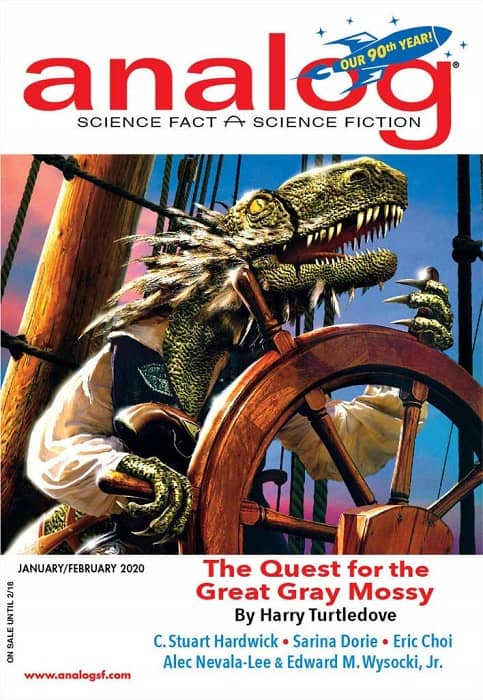

Therefore, when I read the first of a series of decade-specific reprints of “best” science fiction stories published in Analog, I was sensitive to a bit of dialectic about the science/fantasy disparity, one, admittedly, that is twenty years old now. Moreover, in this same issue of Analog, in the present, some mitigation is brought to this topic through Sarina Dorie’s satire “The Shocking Truth About the Scientific Method that Privatized Schools Don’t Want You to Know,” though it, too, has much to say about a post-Enlightenment ideology that appears to somehow have lost its ability to Reason.

Adam-Troy Castro’s and Jerry Oltion’s “The Astronaut from Wyoming” is set in a global milieu of mystery cults, superstitious belief, and “fake news” somehow coexistent with modern technology and “true” scientific understanding. If this doesn’t sound topical and relevant to you at the beginning of 2020, then Stanley Schmidt, in his introduction, makes clear that it should. All of this is fine. There is no inherent sneering at the fantasy genre, though all three ideologies that are vilified are staples of common belief found in most fantasies. But my hyper-sensitive reception detects the merest shadow of potential disparagement for fantasy when, dying on Mars, the protagonist plaintively wonders:

There are more wonders here than we could even begin to imagine… and I’m here to see them because we were crazy enough to come look…. Why can’t that be the thing that excites our imaginations? Why must we waste our minds and our energy on delusions that we should have put aside long ago? … What’s wrong with us? We have brains, we have senses; why can’t we use them to understand the universe around us rather than make up elaborate fantasies and pretend they’re the truth?

The protagonist here appears to be concerned with “wasted” time and energy on whatever is not “real.” In the context of the story, the speaker’s targets specifically are people who believe in folktales about aliens and extraterrestrial abductions and in astrology and — perhaps — a god or other divinities. Yet the impulse behind this character’s frustration, I believe, can be applied quite broadly to many works of the imagination. How does the fantasist defend fancies and wonder tales in the face of this pragmatic and utilitarian claim of science fiction? Does that dreamer even need to?

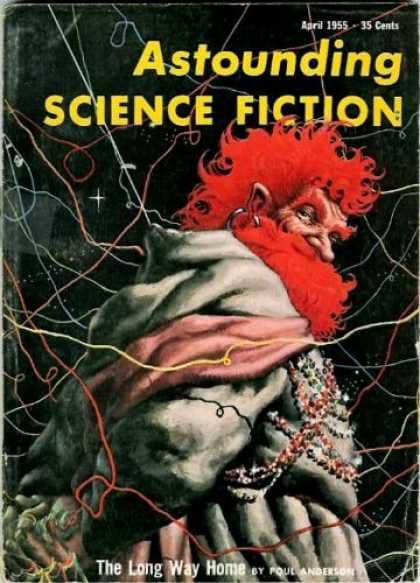

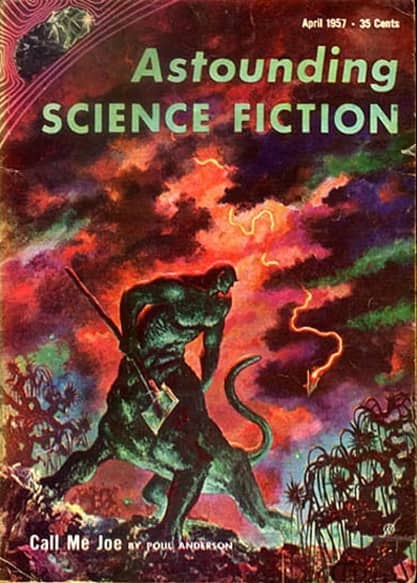

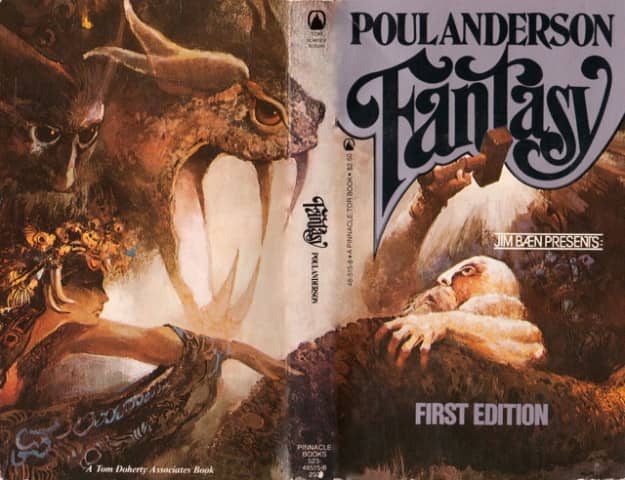

There are many critics we can turn to. Tolkien’s “On Fairy Stories” and Jack Zipes’s Marxist treatments of fairy tales spring to mind. But much more pertinent to this discussion is my man Poul Anderson’s “Fantasy in the Age of Science,” because, in 1981, he addresses this implicit charge directly. Moreover, his defense is the most credible, within this context, because he himself wrote science fiction and fantasy and frequently published in Campbell’s hardminded Astounding Magazine (later Analog).

|

|

|

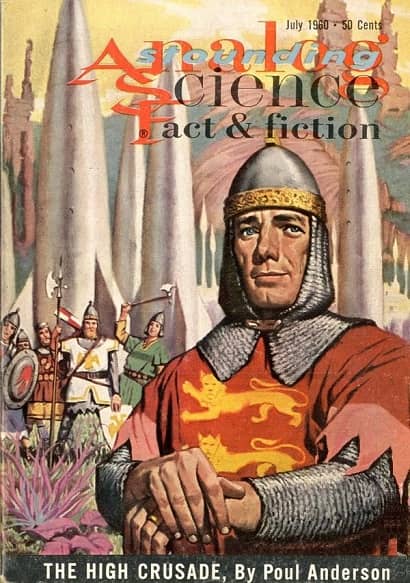

Some of Poul Anderson’s Astounding and Analog cover stories: April 1955 (cover by Frank Kelly Freas), April 1957 (Freas), and July 1960 (Van Dongen)

There is the possibility that every work of the imagination might be conflated in this conversation, and Anderson deftly parses out most of the designations, with a summative defense of many. While bewailing the indisputable “nuttiness” of astrological belief and most superstitions, he briefly defends healthful interests in the supernatural and in certain deities. In fact, in my own life, I find the most prevalent frustration secularists have with religion — this defined as a broad umbrella covering any faith in a beneficial deity — originates most specifically from fundamentalist conceptions that assert literal belief in their traditional mythologies rather than the acceptance of literary criticism and the understanding of holy texts and traditions rightly as profound philosophies illustrated with moralistic tales and parables. I’m not saying that all religious texts are ahistorical; I’m saying that some belief systems don’t differentiate those that are from those that aren’t. In other words, I’m talking here about an understanding — or misunderstanding, as it is — of genre. Science itself grew out of philosophy, and much of what still is considered important to think about — and teach — is Plato’s Classic “what is the Good, and how do you know?” Empirical science can’t hypothesize and test for proof for any answer to this question. Nor even, in the realm of the theoretical, can it propose a model and determine how well reality syncs up with it. This investigation occupies the realm of thought alone, and pushes up against the borders of Mystery.

This is, in part, what I believe fantasy does. It has a purpose distinct from much of science fiction, and, if that objective is devalued by the scientific or fiction-reading community… Well, then, it is asking for a diminishment of human experience and endeavor. I argue that most fantasy concerns itself with the human soul; in it, metaphors are literalized, usually with considerably more sophistication than that found in Medieval morality plays. Fantasy stories — like all stories — are about us as people, though fantasy tales tend to be more timeless, reaching into older, more collective traditions.

Some critics have derided Tolkien, ever since the inception of his popularity, for telling naive fables about Elves and Hobbits, but Elves and Hobbits are us. An Elf is our highest, most long-lived nature. Hobbits prefer comfort with a sacred understanding, and, because of that, they are capable of great feats. In an urban fantasy, someone who is worried about never being noticed might literally disappear. Someone on a first date might learn that the person whom they are with for the night is a soul-eating monster. These tales aren’t idle fantasies — though there is nothing wrong with that, either, if they prove to be so. The armored knight, with a sword, on horseback, off to slay a dragon, means something in regards to the human psyche. These images comprise the language of our Soul.

I’m not saying that we should be uncritical. I know few who are greater critics than I. I’m saying it’s folly and narrow to reject an entire genre simply because of the images, tropes, and “unscientific” milieux it contains. And we can’t. In his own observations about the genre, Anderson says:

With its deep roots in traditions, some of them prehistorically ancient, with its archetypal figures and mysterious events, fantasy likewise helps us maintain our basic humanity. No matter how far we have wandered or how much artifice we have raised around ourselves, we are still creatures of sea and forest, open skies full of wings, sun, moon, stars, the night wind; we were meant to marvel at the world and to stand in awe before the unknown. We can’t go home again to that olden state of being; nor is it desirable that we should; but it is well for us to remember.

In other words, we tell fantasy stories because fantasy springs from the natural world, and we, too, despite all our technological achievements, still are inextricably bound up in that world. So, as says Sarina Dorie’s perspective character in “The Shocking Truth About the Scientific Method that Privatized Schools Don’t Want You to Know,” “I’m Catholic and a science teacher. I can be both. And I can believe in the separation of church and state. I can believe in evolution.” This character isn’t quite talking about the same things as I have been here, but she is addressing supposedly “fanciful” (more often, I maintain, “misunderstood”) conceptions of the universe as a Catholic in contrast to her scientific perspective. I believe the same comment can be made about science fiction and fantasy: I can read both.

In this issue’s Analog, the most entertaining tale, for me, was “One Lost Space Suit Way,” by A.J. Ward, a first published story. Good job! The most lingering in my psyche was Eric Choi’s “The Greatest Day” and its accompanying essay “Saving Columbia: An In-Flight Options Assessment.” The story is an alternate history “rescue” of the space shuttle Columbia on February 1, 2003. The essay elaborates on the background of the story. Good reading.

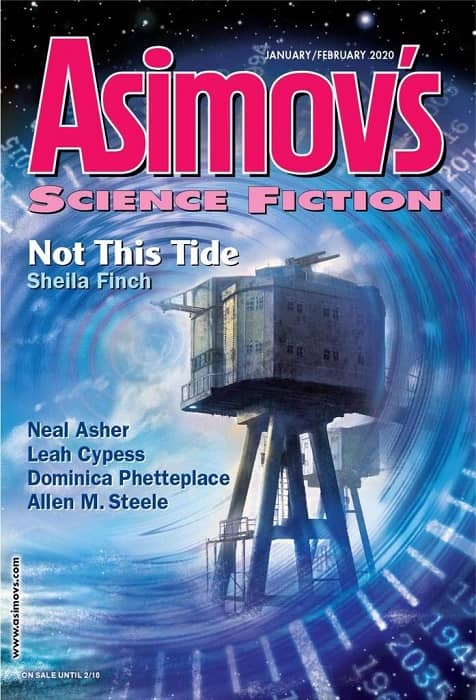

Asimov’s, this bi-month, arrived much later than Analog, and perhaps a reason for this lag is that it came, for the first time in my experience, sealed in a plastic bag. Perhaps Dell is preserving it, for collectors, from the vicissitudes of the mail? I presume O’Neill endeavors to keep all his magazines in pristine shape, but, for me, these are pulps. They disintegrate under my newsprint-stained fingers. Whenever I come across the most ingenious tales (none in either of these magazines, this time around), I tear them out and mail them to friends. If only Asimov’s knew they need not wrap my reading in wasteful plastic. I would be reading electronically, but I can’t share that format with friends.

The two most compelling stories in Asimov’s were (not in order of delivery) the title novella, Sheila Finch’s “Not This Tide,” and Leah Cypess’s “A Pack of Tricks.” Both involved time travel, and, for the two of them, it was this element that produced, in me, some disappointment. As depictions of time and place they are brilliant and immersive. Finch’s is of London during the bombings in WWII. Cypess’s, I believe — this part was a bit puzzling for me — depicts a parallel history analogue for Leonardo da Vinci’s production of the Mona Lisa. But the perspective character and much of the “point” of the story involves the woman who sits for the painting. As works of art, both of these narratives are gorgeous and highly worth reading. As science fiction, the time traveler component seems irrelevant, even distracting. In the first mentioned here, the travelers are present to ensure their future — I guess? — that already has happened. In the second, the “Visitors” are academics hoping to gain deeper insight into their subjects of study. The scholars aren’t supposed to meddle, but, of course, they do, sorta. Both of the tales fall into the “time as fixed” conception of time travel narratives without presenting any further ideas on the subject. Again, the characters involved in the historical milieux are what is interesting; the time travelers are unwelcome and unnecessary, but maybe their absence would preclude publication in a science fiction magazine?

This issue also saw the completion of another serial-length work in Allen Steele’s Arkwright cycle. This one is called “The Palace of Dancing Dogs.” It was okay, a bit underwhelming for such a long and ambitious project. Definitely in the pulp tradition.

Asimov’s Science Fiction and Analog are available wherever magazines are sold, and at various online outlets. Buy subscriptions at the links below.

Asimov’s Science Fiction (208 pages, $7.99 per issue, one year sub $47.94 in the US) — edited by Sheila Williams

Analog Science Fiction and Fact (208 pages, $7.99 per issue, one year sub $47.94 in the US) — edited by Trevor Quachri

The current issues of Asimov’s and Analog are on sale until February 18. See the last article in this series here, and all our recent magazine coverage here.

Work Cited

Anderson, Poul. “Fantasy in the Age of Science.” Fantasy. Tor, 1981.

Gabe Dybing has been a small magazine editor (Mooreeffoc Magazine 2000-2001), often a writer, and usually a gamer. He is most interested in the “northern” fantasy tradition and frequently examines intersections between that topic and gaming. For Black Gate he has contributed many articles, including pieces on Poul Anderson, J.R.R. Tolkien, and roleplaying games. His most recent review of Dell Magazines was More Wondrous and Weird than Fantasy: Dell Science Fiction Reviews.

Haven’t read it yet, but the character in the ANALOG reprint passage seems to me to be bemoaning religion much more than fantasy.

Do fantasists “need” to defend their work? They shouldn’t have to defend the basic nature of fantasy…perhaps a given work, given its strengths and weaknesses. But need to? No.