Fantasia 2019, Day 18, Part 2: The Moon in the Hidden Woods

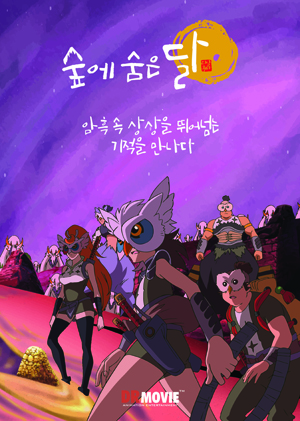

My second film of July 28 screened at the De Sève Cinema. It was an animated film from Korea with a Japanese director, Takahiro Umehara, and it was stunning. Watching early scenes of The Moon in the Hidden Woods (Sup-e Sum-eun Dal, 숲에 숨은 달) I wondered where the movie could go from its opening act — it had already shown us a major city, fights, desert nomads, monsters, a wild variety of costumes and architecture and technologies and designs. Surely, I thought, it would have to slow down. It did; and then built back up again.

My second film of July 28 screened at the De Sève Cinema. It was an animated film from Korea with a Japanese director, Takahiro Umehara, and it was stunning. Watching early scenes of The Moon in the Hidden Woods (Sup-e Sum-eun Dal, 숲에 숨은 달) I wondered where the movie could go from its opening act — it had already shown us a major city, fights, desert nomads, monsters, a wild variety of costumes and architecture and technologies and designs. Surely, I thought, it would have to slow down. It did; and then built back up again.

Long ago, in another world, the moon disappeared and its place was usurped by Muju, the red sky. The world’s been wasting away ever since, but as the film proper opens there is another usurpation, as the ambitious Count Tar claims a throne and the rightful Princess, Navillera, flees rather than be forced to marry him (voice talent for the film includes Lee Jihyon, Jung Yoojung, and Kim Yul, but I cannot find a cast list attaching actors to roles). In the metropolis of Trade City she comes across a drumming contest, and falls in with one of the rival groups, which is led by a youth named Janggu (the word, incidentally, for a specific kind of Korean drum). Helped by Janggu’s allies they flee through a wasteland where terrible Shadows come out under the red sky, and end up at the drummers’ village — where they find a clue that hints at the salvation of the world, to be found deep within the mysterious Hidden Woods.

The movie’s not just constantly visually creative, but a fascinating mix of sensibilities. There’s a post-apocalyptic feel here, as this world has been rebuilt in the shadow of a great tragedy, but there is also steampunk in its technology. And a traditional mythic fantasy feel in the way the social structure’s set up (the casual acceptance of monarchy, for example) and in the use of elements like music and community ritual. Above all the worldbuilding is incredibly rich in the way different places are not just designed differently but also mix different visual elements. Cities feel like cities, with a variety of fashions and cultures.

Character design is relatively realistic, but with a cartooniness that plays well in comic moments. Still, this is far from the anime approach of simply-drawn characters against a hyper-realistic background. The film’s all of a piece, and there’s an almost relaxing reliance on traditional 2D drawn imagery over 3D CGI. There is some well-used computer imagery, but the look of the movie’s traditional. It is in fact a thoroughly well-done children’s or YA film, something that plays well for adults but (I would think) particularly speaks to a younger audience. Navillera and Janggu are our leads, the people about whom the tale revolves. The other characters are well-drawn, but relatively uncomplicated. There is a slight implication of some of the adult characters having a relationship that might play differently to older viewers, in terms of their emotional tone, but that’s left understated.

With all of this, there’s a solid plot that moves quickly through a number of stages. The characters journey about quite a lot, and we get to know the different places they go surprisingly well; in a relatively short amount of screen time we come to have a sense of a city, a town, a lost labyrinth. The world feels bigger than the story in just the right way. That is, there always seems to be more wonderful and fantastic things just off the edge of the frame. Everything comes together in the end, narratively and thematically, but the movie doesn’t feel like it’s exhausted itself.

With all of this, there’s a solid plot that moves quickly through a number of stages. The characters journey about quite a lot, and we get to know the different places they go surprisingly well; in a relatively short amount of screen time we come to have a sense of a city, a town, a lost labyrinth. The world feels bigger than the story in just the right way. That is, there always seems to be more wonderful and fantastic things just off the edge of the frame. Everything comes together in the end, narratively and thematically, but the movie doesn’t feel like it’s exhausted itself.

It’s a story with a number of ideas, but surely near its heart is the importance of the environment and maintaining a functioning ecology. Greed and power have thrown the balance of the world out of whack, and it’s up to the new generation to set things right. That’s a strong approach, and it works here.

But at the same time there’s something a little bigger in the film. There’s an angle in which it’s about the point where the world meets myth. The human story of usurpation reflects and is reflected in the story of the heavens. To use a word that I have used before in these reviews, this is a mythopoeic story, one in which something transcendental is reflected through the armature of a secondary-world fantasy. There are moments in this film, as the characters encounter particularly potent forces, that approach the psychedelic not in the usual sense but in the etymological root: the soul is made visible, not an individual soul so much as a soul of the world or the heavens.

I don’t want to imply that the film’s heavy or religious in any obvious sense. But the respect for nature has a sense of almost animist immanence. There’s an importance and meaning to the natural world that gives the story a centre. It is clearly a fantasy-adventure story, and a fun one. The structure’s a good genre structure, with familiar elements of fairy-tales and quests. But it does what great fantasies do, and touches on moments that fill the story with a meaning that’s larger than the plot alone can explain.

I don’t want to imply that the film’s heavy or religious in any obvious sense. But the respect for nature has a sense of almost animist immanence. There’s an importance and meaning to the natural world that gives the story a centre. It is clearly a fantasy-adventure story, and a fun one. The structure’s a good genre structure, with familiar elements of fairy-tales and quests. But it does what great fantasies do, and touches on moments that fill the story with a meaning that’s larger than the plot alone can explain.

What may be most impressive, when all’s said, is how well the film juggles its variety of ideas. There are a lot of concepts, locations, characters, and plot points. But they don’t feel as though they’re struggling for attention. They fit nicely, each with the other, in only 97 minutes. That’s impressive; post-apocalyptic steampunk in the first act gives way to scenes of village life gives way to fantasy quest into a lost forest gives way to a grand climax, and it all feels coherent. I might quibble that Navillera’s role in the climax is a bit passive, as the other characters work to set up things to give her a star turn, but quibbling is what that would be.

The Moon in the Hidden Woods is an excellent fantasy for young viewers that should appeal to adults. It’s filled with creative imagery, and moments of real wonder. It’s a film that doesn’t just do what it tries to do, but manages to be perhaps the best possible version of what it is. I enjoyed it and was impressed by it.

After the film, director Takahiro Umehara took questions. The first was about the soundtrack, and how important music was to the movie. Umehara said that when he was originally requested to direct the film the story did not include music. The original idea for the film actually drew from a European aesthetic, which he was relatively unfamiliar with. He wanted to include music in the movie, and also include a Korean aesthetic. He wanted his team to be able to include something personal to them, their own particular context.

After the film, director Takahiro Umehara took questions. The first was about the soundtrack, and how important music was to the movie. Umehara said that when he was originally requested to direct the film the story did not include music. The original idea for the film actually drew from a European aesthetic, which he was relatively unfamiliar with. He wanted to include music in the movie, and also include a Korean aesthetic. He wanted his team to be able to include something personal to them, their own particular context.

Asked if the story was based on any original legend, he said there was no legend in particular, although in Korea, Japan, and much of Asia, there are ideas of celebrating the moon and nature. He said he was attracted to the power of humans with a sense of community and a festive sense, and avoiding violence and killing, instead emphasising camaraderie. He said (if I interpret my handwritten notes correctly) that he hoped there were festivals in Canada that audiences could use to interpret the context of the film.

Asked if he was influenced by Miyazaki and Studio Ghibli, particularly in terms of the script, he said of course. He said that he feels he is one of Miyazaki’s children or grandchildren, and that when things got difficult or challenging he would ask himself “What would Miyazaki-san do?”

Asked if there were any challenges being a Japanese director in Korea, he said that while there were tensions between Korea and Japan on the level of foreign relations, in animation the countries have supported each other since the 1970s. Because of this exchange, more and more Korean animated films are being made, and more Korean animators are emerging. He said he would like everyone regardless of nationality to be able to come together to make artwork, and reflected on a walk he’d taken earlier that day through Montreal’s Old Port, thinking about all the cultures that came together to create the city, and how he would like to see that sort of thing in animation.

Asked if there were any challenges being a Japanese director in Korea, he said that while there were tensions between Korea and Japan on the level of foreign relations, in animation the countries have supported each other since the 1970s. Because of this exchange, more and more Korean animated films are being made, and more Korean animators are emerging. He said he would like everyone regardless of nationality to be able to come together to make artwork, and reflected on a walk he’d taken earlier that day through Montreal’s Old Port, thinking about all the cultures that came together to create the city, and how he would like to see that sort of thing in animation.

Asked about his next project, he said he can’t speak publicly about it, but he does have a project that will come to light in the next couple of years. Asked what’s next for The Moon in the Hidden Woods, he said he’s not really sure. He said being selected for Fantasia was important for him and for the film, and it will be important to have it released in Japan and Asia. Asked if there was any inspiration in the movie from video games such as Final Fantasy, he said yes, of course, and would have liked to emphasise the influence even more so gamers would be able to get into it.

Asked about the inspiration for the characters, Umehara said he wanted the Princess to embody Korean cultural elements and indeed Asian cultures generally, and so, for example, her eyebrows were drawn as brushstrokes. He suggested that the specific cultural elements encoded in the characters might not be clear, but might inspire the audience to look further, and come back to the film and see more.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.