One Shot, One Story: Ray Bradbury

Enmeshed as we are in the world-shaking spectacle that is the 2015 NBA finals, this might be an appropriate time to take a break from the struggle of the Hobbits (Stephen Curry, Klay Thompson, and their Golden State Warriors) against the dominion of the Dark Lord (LeBron James and the Cleveland Cavaliers) and remember back to the last improbable time that professional basketball was mentioned on Black Gate.

Enmeshed as we are in the world-shaking spectacle that is the 2015 NBA finals, this might be an appropriate time to take a break from the struggle of the Hobbits (Stephen Curry, Klay Thompson, and their Golden State Warriors) against the dominion of the Dark Lord (LeBron James and the Cleveland Cavaliers) and remember back to the last improbable time that professional basketball was mentioned on Black Gate.

That was in my article of last October, “One Shot, One Story: Clark Ashton Smith,” which was inspired by a discussion I had with a fellow NBA addict in which we debated the burning question, “If you had to pick one player to make one shot — to save your life — who would it be?” Once our argument had run its course, I started thinking about a different form of acrobatic exhibitionism — writing, which led to a related question: If you had to introduce a prospective reader to the work of Clark Ashton Smith with just one story, which story would you choose?

If you’re dying to know the sporting and literary answers to those queries, read the old article; it’s not bad, and I’m already thinking about an All-Fantasy Greats basketball team… let’s see, H.P. Lovecraft at point guard creating for his teammates, finding that punishing inside player Robert E. Howard in the post, or kicking out to Clark Ashton Smith for a deep three pointer… woah. Somebody had better stop me before I get silly…

I answered the Smith question (to my own satisfaction, anyway) in that earlier piece, but the notion of finding one story to present the fundamental qualities of a writer to an uninitiated reader stuck with me; there are countless writers it could be applied to.

And now, the current clash of roundball titans has at last inspired the next variation on my initial question (you were waiting on pins and needles, right?), and here it is — if you had a reader, open but unfamiliar with the work of one Ray Douglas Bradbury, and had to pick one story to introduce the Wizard of Waukegan with, (to save your life!) which one would it be?

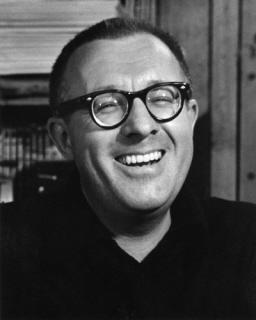

Admittedly, this requires some suspension of disbelief, for while Clark Ashton Smith is a writer who remains obscure to even many avid fantasy readers, it is hard to believe that there is anyone who reads English who has not encountered Ray Bradbury; once you’ve made it into middle-school textbooks your victory is assured, and his conquest of American culture is so complete that any day now I expect to see his benign features beaming down from the heights of Mount Rushmore or bouncing Andy Jackson off the face of the twenty dollar bill. (Come to think of it, Ray may already be on the twenty dollar bill; I haven’t seen one for so long, I’m not sure.)

For the moment though, let’s assume that such uninformed creatures exist, ready to be beguiled by a tale from this author as yet unknown to them; the only thing that remains is to bait the hook.

Again, as in the case of Smith, we’re not necessarily talking about using Bradbury’s best story, however one would define that (thought it should certainly represent his strongest work), but a story that displays his essential qualities, a story that, once finished, will leave the reader in no doubt as to who this man is and what he has to offer.

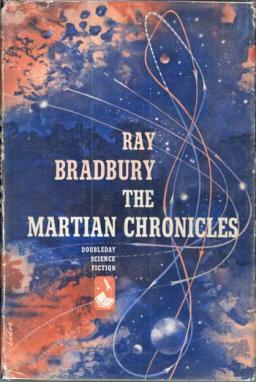

Ray Bradbury seemingly presents us with a wider field of choice than Smith did, writing over six hundred stories in a career that began before World War Two and ended just a few years ago, while Smith wrote slightly more than one hundred stories, almost all them produced during a period of ten years beginning in the late twenties. The task is not that much larger, however. Most of the stories that Bradbury is best remembered for were written from the mid nineteen forties through the end of the fifties, a span not much longer than Smith’s active period. Say “Ray Bradbury” to most people, and it is likely that the first thing that will pop into their minds will be a story from this fruitful period. He continued to do fine work right up until the end, but it was this early phase that defined him as a writer. But defined him how?

If Smith’s essential quality is a jeweled, sardonic decadence, what is the essential Ray Bradbury quality, the quality that makes him distinctive and unforgettable?

Most of Bradbury’s stories lyrically depict a sentimentally idealized world, a kind of paradise. In his weaker stories, the sunshine and sentiment go all the way to the core, and the sweetness can become cloying. But in his finest work, he remembers that no Eden is complete without its serpent; smiles are masks, and when you lean close to inhale the lovely scent of the dew-covered rose, be sure that a black widow will crawl from underneath the fragrant petals. The essential quality of Bradbury’s most memorable work is this sense of the evil and corruption lurking just beneath the bright, fresh-scrubbed surfaces of ordinary life, ready to break out at any moment. His best tales are coins with two very different faces.

Most of Bradbury’s stories lyrically depict a sentimentally idealized world, a kind of paradise. In his weaker stories, the sunshine and sentiment go all the way to the core, and the sweetness can become cloying. But in his finest work, he remembers that no Eden is complete without its serpent; smiles are masks, and when you lean close to inhale the lovely scent of the dew-covered rose, be sure that a black widow will crawl from underneath the fragrant petals. The essential quality of Bradbury’s most memorable work is this sense of the evil and corruption lurking just beneath the bright, fresh-scrubbed surfaces of ordinary life, ready to break out at any moment. His best tales are coins with two very different faces.

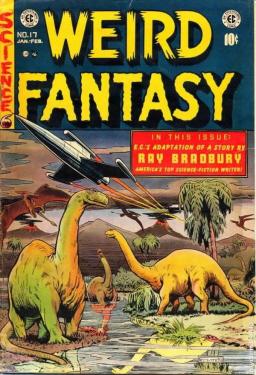

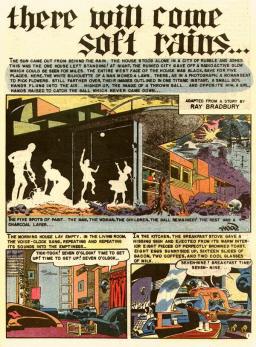

So many of Bradbury’s stories fall into this category that there is no shortage of legitimate choices, and one of the best is “There Will Come Soft Rains,” which was published in Collier’s in its May 1950 issue, and which Bradbury later expanded for inclusion in The Martian Chronicles. It has also been adapted several times for radio, and there have been multiple comic book versions of the story, the most notable appearing in EC’s Weird Fantasy 17 in 1953, with art by Wally Wood.

In summary, the story is quite simple. Set in 2026, it is an hour-by-hour chronicle of a day in the “life” of a house. All of the everyday functions of the dwelling are completely automated; at seven in the morning the house sounds an alarm (in the form of a rhyming, sing-song recorded voice) for getting out of bed, and as the day progresses the house proceeds to cook the meals, wash the dishes, clean and vacuum the rooms, mow and water the lawn, open and close doors, entertain the children, provide recorded-voice reminders for birthdays and anniversaries and for paying the bills, choose and read an evening poem to the tune of soothing music… it does everything, in fact, for its owners, to insure a frictionless day of comfort and ease. (Bradbury is usually not thought of as a strongly predictive writer from the school of “hard” science fiction, but here he uncannily portrays what we now call a “smart” house.)

The house is all cleanliness and order, all bright shine and rational routine, the idealized magazine-ad nineteen fifties household heightened to the nth degree, with a place for everything and everything in its place… almost.

Bradbury very quickly lets us know, however, that this structure is not just a miracle of modern science, it is in fact unique, because it is alone — the sole survivor, the last of its kind:

The house stood alone in a city of rubble and ashes. This was the one house left standing. At night the ruined city gave off a radioactive glow which could be seen for miles.

But there is no one to see it. The house is as empty as the shattered city that surrounds it. All of the automated tasks are done for no one; all of the reminders and cheerful rhymes have no audience to listen, for there is no one left to hear. The poem randomly chosen and read to the mother echoes from the walls of an empty room; there is no mother to reflect upon its beauty. The cigar lit and placed for the relaxation of the father burns down to cold ashes, unenjoyed; there is no father to smoke it. The three-dimensional animal show flashed upon the nursery walls for the entertainment of the children finds no delighted response; there are no children to watch and laugh.

But there is no one to see it. The house is as empty as the shattered city that surrounds it. All of the automated tasks are done for no one; all of the reminders and cheerful rhymes have no audience to listen, for there is no one left to hear. The poem randomly chosen and read to the mother echoes from the walls of an empty room; there is no mother to reflect upon its beauty. The cigar lit and placed for the relaxation of the father burns down to cold ashes, unenjoyed; there is no father to smoke it. The three-dimensional animal show flashed upon the nursery walls for the entertainment of the children finds no delighted response; there are no children to watch and laugh.

All that remains of the family is outside, negative shadows upon a burned wall:

The garden sprinklers whirled up in golden founts, filling the soft morning air with scatterings of brightness. The water pelted windowpanes, running down the charred west side where the house had been burned evenly free of its white paint. The entire west face of the house was black, save for five places. Here the silhouette in paint of a man mowing a lawn. Here, as in a photograph, a woman bent to pick flowers. Still farther over, their images burned on wood in one titanic instant, a small boy, hands flung into the air; higher up the image of a thrown ball, and opposite him a girl, hands raised to catch a ball which never came down.

The inhabitants of this nameless city created a place of technological perfection, believing that in taming nature they had tamed themselves, forgetting that the power that creates can just as easily destroy — if not more easily. They had forgotten that there is a darkness that is always waiting for its chance to damn an individual or wreck a world, and their picturebook-pretty lives could not prevent it from consuming them.

As the day dwindles down, a note of hysteria creeps into the house’s automated voice; it almost seems to know that something is radically amiss. The starving family dog gets into the house and dies; it is whisked away by cleaning robots and burned up in an incinerator “which sat like evil Baal in a dark corner.” The programmed routine continues on, however, until a storm blows down a tree and a branch smashes into the kitchen through a shattered window, starting a fire.

The house valiantly battles the blaze, seeking in its own way to contain rogue nature just as its builders had, but ultimately, like its vanished masters, failing and dying. Had those evaporated millions also perished in a last frenzy of meaningless activity, seeking some solace or reassurance in the everyday activities that had always sustained them? If so, the house can only follow their lead:

In the last instant under the fire avalanche, other choruses, oblivious, could be heard announcing the time, playing music, cutting the lawn by remote-control mower, or setting an umbrella frantically out and in the slamming and opening front door, a thousand things happening, like a clock shop when each clock strikes the hour insanely before or after the other, a scene of manic confusion, yet unity; singing, screaming, a few last cleaning mice darting bravely out to carry the horrid ashes away! And one voice, with sublime disregard for the situation, read poetry aloud in the fiery study, until all the film spools burned, until all the wires withered and the circuits cracked.

In the end, nothing is left standing except one lone wall, and within it a last taped voice idiotically repeating the date, August 5, 2026, over and over and over until its power fails and leaves only a final silence.

In the end, nothing is left standing except one lone wall, and within it a last taped voice idiotically repeating the date, August 5, 2026, over and over and over until its power fails and leaves only a final silence.

All of Ray Bradbury’s key qualities are on display in this classic tale — his lyrical, poetic language, his sense of the tragic fragility of human life and achievement, his anxiety over the loss of human identity, his idealized view of the family, his underrated predictive powers, and above all, his sense of the abyss that all bright and brave things are poised over, his knowledge of the unavoidable double nature of life, the inevitable darkness that is an always present element in all things human. It is this sense that time and again rescues him from the pitfalls of sentimentality and gives his vision an edge that cuts.

So many of Ray Bradbury’s greatest stories have this spider in the sugarbowl quality — “The Pedestrian,” “Pillar of Fire,” “Zero Hour,” “The Small Assassin,” “All Summer In a Day,” “Hail and Farewell” — one of the most effective of all, for in that story touching and creepy are in such a perfect balance that it is possible to respond to the story in a different way every time you read it.

“There Will Come Soft Rains” (the title comes from the Sarah Teasdale poem that the house reads to the incinerated mother, a poem ironically about a nature indifferent to human beings) doesn’t offer the whole of Ray Bradbury, of course — he was too rich and wonderful a writer for any one story to do that, but it does give a fair feeling of his sensibility, and of his strengths — and quirks — as a writer.

There are many other Bradbury stories that could do just as well to hook the prospective reader, so many indelible moments and images from so many classics, so many favorites — which one would you choose… to save your life?

When you posed the question, the story that immediately sprang to mind was “There Will Come Soft Rains,” so you’ve got that covered.

I’ve read quite a bit of Bradbury, and that story above all just sticks with me, so haunting. That might be one of the great stories of the twentieth century, period. And not a single character in it! (Not a living character, anyway, unless you count the dying dog.)

He wrote a lot of great stuff, and is rightly regarded as one of the great twentieth-century writers. And some not-so-great stuff. As you say, some of his work could get a bit too sentimental and maudlin — an over-flowery attempt to evoke a small-town Illinois childhood. But when it worked, man it worked.

And that story. That is the one that shows he was a literary genius.