A Gateway to Fantasy for Young Readers: Amulet by Kazu Kibuishi

With the height of the “Harry Potter phenomenon” nearly a decade past, we now have a new generation of seven- and eight-year-olds who were born after the final book in that series came out. A perennial question comes up: What will be the next “gateway” work that ushers young readers into a lifelong love of fantasy and speculative fiction?

With the height of the “Harry Potter phenomenon” nearly a decade past, we now have a new generation of seven- and eight-year-olds who were born after the final book in that series came out. A perennial question comes up: What will be the next “gateway” work that ushers young readers into a lifelong love of fantasy and speculative fiction?

Well, some may rightly ask, why can’t it be Harry Potter? Or A Wrinkle in Time, or The Dark is Rising sequence, or The Chronicles of Prydain, or The Chronicles of Narnia, or The Hobbit, or The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, or…?

Many do still find their first taste of enchantment in books that are decades or even a century old, but there is no denying that — at least in the publishing and bookselling world — there has to be a “latest model.” Librarians still push those beloved older books faithfully, but their sales pitch is a lot stronger when it comes as a follow-up to a young reader who, having just read something that is currently “all the rage,” asks, “What else out there is like this?”

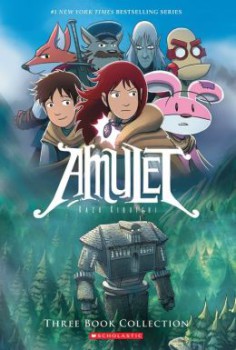

I’m here today to suggest that if you want a contemporary work that will introduce 3rd to 7th graders to the pleasures of epic fantasy, steampunk, people with animal heads, and wise-cracking robots, you could do a lot worse than hand them the graphic novel Amulet Book One: The Stonekeeper (2008) by Kazu Kibuishi. But be prepared: odds are good that they will immediately be demanding books 2 through 6. And then they will be waiting with bated breath for book 7 and cursing that there is now a two-year interval between volumes (welcome, Young Reader, to the Pains of Following a Series that is Ongoing. To better understand what you are in for, see any conversations referencing George R.R. Martin or Patrick Rothfuss).

But I’m also here to recommend them to anyone who likes this sort of stuff, regardless your age. I mentioned “3rd to 7th graders” in the last paragraph because those are the perimeters the publisher, Scholastic, says they are written toward. As someone who does not fit that demographic, I can vouch for them being worthwhile reads even if you are middle-aged.

Perhaps more so! I am reminded of the great quote from C.S. Lewis:

“When I was ten, I read fairy tales in secret and would have been ashamed if I had been found doing so. Now that I am fifty, I read them openly. When I became a man I put away childish things, including the fear of childishness and the desire to be very grown up.”

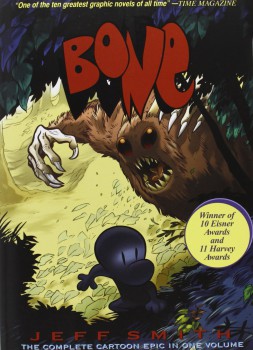

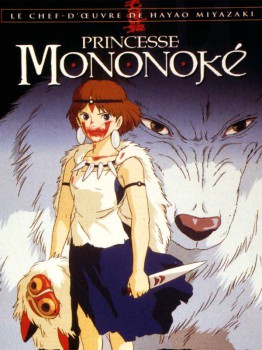

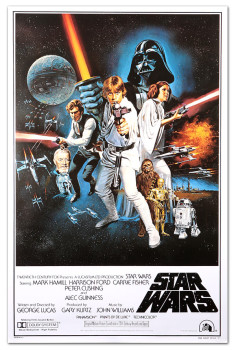

What do I mean by “this sort of stuff”? Well, the influences on Kibuishi are clear, and he is upfront about them: the films of Hayao Miyazaki, Star Wars, The Neverending Story, Jeff Smith’s Bone graphic novels. I also detected in key points of the narrative the possible influence of Nickelodeon’s Avatar: The Last Airbender series (2005-2008) [either direct influences or else some really strikingly coincidental parallels — more on that later]. Skimming the Internet to see if he’d made any overt references to this influence, I did happen to discover that his wife, fellow graphic artist Amy Kim Kibuishi, has done some illustrating for new Avatar stories. So, on strong circumstantial evidence, I’d say my hunch there is confirmed.

What do I mean by “this sort of stuff”? Well, the influences on Kibuishi are clear, and he is upfront about them: the films of Hayao Miyazaki, Star Wars, The Neverending Story, Jeff Smith’s Bone graphic novels. I also detected in key points of the narrative the possible influence of Nickelodeon’s Avatar: The Last Airbender series (2005-2008) [either direct influences or else some really strikingly coincidental parallels — more on that later]. Skimming the Internet to see if he’d made any overt references to this influence, I did happen to discover that his wife, fellow graphic artist Amy Kim Kibuishi, has done some illustrating for new Avatar stories. So, on strong circumstantial evidence, I’d say my hunch there is confirmed.

It is quite a mix of elements: talking animals, talking robots, talking trees, stonekeepers wielding mystic power, dark elves, Lovecraftian tentacled thingies, giant fighting robots, walking houses. There are some dark elements to the story, but loads of humor. Kibuishi pulls off the rare feat — like Smith in the Bone books — of throwing all these disparate elements together and somehow making them work. It’s not an easy feat, what with this many ingredients thrown into the story cauldron.

Unlike the Bone books and most other comic series, these are not being released in installments as an ongoing comic. Each new volume comes out as a complete graphic novel, usually about a year in the making, encompassing enough material to have been about a 7 to 10-issue run of a monthly or bimonthly series (Book Six is 216 pages). Having the support of a publisher like Scholastic (under their Graphix imprint) for this approach gives Kibuishi some freedom with pacing: the work does not feel serialized; each book stands as a complete arc. I have read each one in a single sitting, and they just fly by. A lot happens, but the extra room provided by each one being a single 200+ page comic allows the art to breathe, the action to be beautifully choreographed, and the occasional — breathtaking — two-page spread.

Unlike the Bone books and most other comic series, these are not being released in installments as an ongoing comic. Each new volume comes out as a complete graphic novel, usually about a year in the making, encompassing enough material to have been about a 7 to 10-issue run of a monthly or bimonthly series (Book Six is 216 pages). Having the support of a publisher like Scholastic (under their Graphix imprint) for this approach gives Kibuishi some freedom with pacing: the work does not feel serialized; each book stands as a complete arc. I have read each one in a single sitting, and they just fly by. A lot happens, but the extra room provided by each one being a single 200+ page comic allows the art to breathe, the action to be beautifully choreographed, and the occasional — breathtaking — two-page spread.

Publishers Weekly summed up Amulet with this blurb: “Stellar artwork, imaginative character design, moody color and consistent pacing.” I’ll expound on that a bit before getting into the story itself.

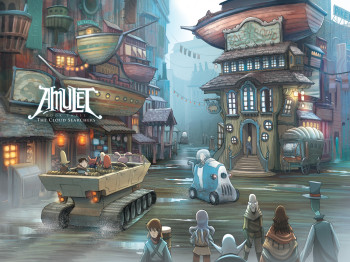

Kibuishi’s characters are fluid, simple, and dynamic; they have a strong animation influence (I was not surprised to learn from his bio that he started out professionally in animation). The way he draws the robots and the people with animal heads is “cartoony” at its best. But the world — the natural elements and the buildings and the bustling streets — is where the artwork really shines. There is a depth to the backgrounds reminiscent of old-school Disney — lush settings that you want to step into and walk around in. While Kibuishi is the writer and illustrator, the credits also list a Lead Production Artist (Jason Caffoe) and a whole team on “Colors and Background”: seven people including Kibuishi. There are also five people responsible for “Page Flatting” (which I have no idea what that is). In other words, the production credits are more reminiscent of an animated film than are most comic books. Point being, there’s a lot that goes into the visuals of this book. And it shows in every panel of every lavish page.

Now, to the story those visuals are in service of…

I sort of discovered Amulet through Bone (when I finished the latter series this past winter, I noted the many “If you enjoyed Bone” prompts pointing me to check out Amulet, which my local library also happened to have), so I’ll give Jeff Smith the first word here. In his blurb, Smith raves, “Five — no, three pages into Amulet and you’ll be hooked.”

That’s undoubtedly true for many readers (it is a New York Times Bestselling Series, has received heaps of Young Readers’ awards, and, according to Kirkus Reviews, is “a must for all fantasy fans”). As a reader who knew nothing about it going in, though, I can say that the way the series opens is a bit misleading. Not in a bad way — you just don’t know what you’re in for.

It starts quite grimly, the opening scene vividly playing out in present tense a car crash that claims the life of the father of our young protagonists, who are in the back seat and witness his death firsthand. Then, to quote the summary from Wikipedia:

“They along with their mother, Karen, move to their great-grandfather’s house in a town after their father, David, died in a car accident and she can’t afford to pay the rent. The locals believe that the house is haunted, but Karen ignores the rumors. But soon, the family discovers a small door in the basement of the house leading to an alternate version of earth.”

Twelve-year-old Emily and her younger brother Navin have to delve through that terrifying basement door because their mother is dragged through it by a slimy tentacled thing. And at this point in the story — what with haunted basements and tentacled monstrosities from another dimension — I thought I was in for a Lovecraftian watered-down-for-young-readers excursion.

Twelve-year-old Emily and her younger brother Navin have to delve through that terrifying basement door because their mother is dragged through it by a slimy tentacled thing. And at this point in the story — what with haunted basements and tentacled monstrosities from another dimension — I thought I was in for a Lovecraftian watered-down-for-young-readers excursion.

I was quickly disavowed of that initial impression when the first people Em and Nav encounter as they try to rescue their mother from the arachnopod include a rogue elf prince and several robots — one of them designed to look like a pink bunny, the others looking like they clanked their way out of a steampunk version of The Jetsons.

The characters they meet as they explore more of this world get ever more colorful (including a whole city whose inhabitants are under a curse that transforms them into hybrids of various animals — hence characters like the fox-headed warrior Leon Redbeard).

Em and Nav find their way to the otherworld-home of their great grandfather, who is still alive just long enough to tell Emily some portentous words about her responsibility as a Stonekeeper. You see, before they left the house to save their mother, Em found an amulet with a pink stone in her great grandfather’s library, which she now wears around her neck. Turns out it has great power, and had been the amulet of her great grandfather, who was on the Guardian Council of Stonekeepers in the world of Alledia. But all those pieces slowly fall together later in the series, as the protagonists unravel the secrets and dangers of this new world.

Also, Em’s stone has a voice and talks to her. It refers to her as “Master,” but is always pushing to get her to give herself over and let it take full control (shades of Lord of the Rings with the corrupting influence of using the Ring of Power).

I was never thrown, though, as the story expands and brings in increasingly diverse elements (steampunk technology of the elves that includes giant dirigible warships and other flying craft, floating cities, and intelligent robots). Kibuishi paces the story so deftly that I was all strapped in, enjoying the ride wherever it took me next.

Kibuishi gradually introduces a rich, varied, and complex cast of characters who weave in and out of the main narrative. Our young protagonists on their hero’s journey collect a ragtag, motley bunch of half-animal rebels, robots, rogue elves, a wise old mentor in the form of a grizzled former member of the Guardian Council — and even a walking house a la Baba Yaga’s hut or Howl’s Moving Castle. Characters like the grumpy robot Cogsley bring humor to the mix, while other characters bring a more somber element of tragedy. The combination really reminds one of the early Star Wars films, and it works great here.

Kibuishi gradually introduces a rich, varied, and complex cast of characters who weave in and out of the main narrative. Our young protagonists on their hero’s journey collect a ragtag, motley bunch of half-animal rebels, robots, rogue elves, a wise old mentor in the form of a grizzled former member of the Guardian Council — and even a walking house a la Baba Yaga’s hut or Howl’s Moving Castle. Characters like the grumpy robot Cogsley bring humor to the mix, while other characters bring a more somber element of tragedy. The combination really reminds one of the early Star Wars films, and it works great here.

Kibuishi was born in Tokyo, Japan, but moved to the U.S. in 1982 when he was about four years old. In a 2010 interview with Japan Cinema blog he said that as a young boy he lamented the lack of “cool robot TV shows like Ultraman” in his new home (not yet, anyway — early ‘80s we were just on the cusp of the Japanese pop-culture invasion: pretty soon we’d have more Tokyo monsters and giant robots than you could shake a Mighty Morphin Power Ranger at). Kibuishi’s work combines so many pop-cultural elements of both the country of his birth and the U.S., I am impressed by how seamlessly it does so. To find oneself experiencing the pleasures one derives from Star Wars and from a Miyazaki film on the same page is a real treat.

Yes, a lot of this is homage; Kibuishi admits as much: he is working in all the elements of the popular entertainment that he loved growing up. He said in a 2011 interview with the website popmatters that he is ultimately writing a work aimed at his own 10-year-old self: “I just want my younger self to get a hint of what he might be able to expect in the near future, while also remembering that he should have fun. My hope is that the books help him be stronger, and less fearful.” [You can read the full interview here.]

The various characters and plot points (even a lot of the designs) may seem very familiar, but that familiarity here is part of the fun for a reader my age: it is a veritable cornucopia of all the best touches that we remember so fondly in our most beloved films, comics, and video games. Kibuishi says:

“I feel like my books are a bridge to all the great books, movies, and games I enjoy as an adult. I was never more excited about comics than when I was a little boy and I try to remember that when I go to work everyday” (popmatters).

I am one reader who can attest to that, and who will say that Amulet is so far a worthy bridge — or gateway.

![]() And it works for more than just young readers because Kibuishi gives us dynamic, layered, conflicted characters — even the baddies have motives that we can understand and sympathize with. In this I would credit the influence of Miyazaki (Disney never got this right, with their one-dimensional cardboard villains). Another strong example, again, is the Avatar: The Last Airbender series. [SPOILER for both series in the remainder of this paragraph!] One striking parallel between that show and Amulet is that one of the initial villains turns against the Overlord and joins the protagonists. In both cases, in fact, the character who switches allegiance happens to be the son of the Big Bad. Both characters are initially motivated by a need to impress and live up to their fathers. They both disappoint their father by not being able to capture the protagonists. Eventually, through painful revelations of the father’s true nature and some serious soul searching (with the aid of an older, wiser mentor who happens to be another family member no longer completely loyal to the father), they switch sides to oppose their Dark Lord daddy.

And it works for more than just young readers because Kibuishi gives us dynamic, layered, conflicted characters — even the baddies have motives that we can understand and sympathize with. In this I would credit the influence of Miyazaki (Disney never got this right, with their one-dimensional cardboard villains). Another strong example, again, is the Avatar: The Last Airbender series. [SPOILER for both series in the remainder of this paragraph!] One striking parallel between that show and Amulet is that one of the initial villains turns against the Overlord and joins the protagonists. In both cases, in fact, the character who switches allegiance happens to be the son of the Big Bad. Both characters are initially motivated by a need to impress and live up to their fathers. They both disappoint their father by not being able to capture the protagonists. Eventually, through painful revelations of the father’s true nature and some serious soul searching (with the aid of an older, wiser mentor who happens to be another family member no longer completely loyal to the father), they switch sides to oppose their Dark Lord daddy.

One character who does take a back seat after the second book is the mother, Karen. The kids rescue her — motivating plot element of book one — and then have to hunt down a rare fruit in order to heal the sting she received from the arachnopod — motivating plot element of book two — and after that she just tags along while they assume their mantles of destiny as prophesied saviors of this world. She steps in occasionally to make worried mom pronouncements: In book three or four, Emily is about to go into a disreputable port bar with Leon to hire a dirigible captain (where have we seen this setup before? Mos Eisley cantina, of course). She says something along the lines of “You’re taking my 12-year-old daughter into a bar? I don’t want her going in there!” But her objections are gently ignored as her children carry on being the saviors this world needs.

Of course, when you think about it, the adventures that children encounter in any portal story ever would be enough to give their parents or legal guardians conniptions ranging from heart palpitations to a nervous breakdown. Just consider the Pevensie children being declared kings and queens of Narnia who are destined to defeat the White Witch in The Lion, The Witch, and the Wardrobe (1950), or the Drew children getting caught up in the war of the Old Ones in Over Sea, Under Stone (1965). “You want my 11-year-old to slay a giant wolf with a sword? Don’t I need to sign a consent form first?”

Sherwood Smith wrote a wonderful story addressing this very issue called “Mom and Dad at the Home Front” (published in Realms of Fantasy, August 2000), which was collected in David Hartwell’s Year’s Best Fantasy. That story portrayed the parents’ point of view after they discover their children have been slipping off via a magical portal to some fairy-tale land where they’ve been doing the requisite things portal-kids do to save the other world and free its denizens from its supernatural tyrant. At first the parents react the way any parent would: they lock the magic wand or key (I can’t remember what the portkey was, exactly) away and ground the kids from any further adventures in mystical realms. But then they gradually come to realize that their children have been given a destiny, and that thousands will suffer or die if they hinder that calling. They, like their children, are unwittingly part of a larger narrative, and in keeping their children home they are aiding the dark lord of that other world. I won’t tell you what the parents end up doing — it’s a story worth tracking down for yourself.

In the case of Emily and Navin’s mother Karen, she seems to recognize the significance of what her children have been called to do in this otherworld and is generally supportive, giving encouragement and moral support. We haven’t yet seen much real portrayal of how utterly horrified she must be at the thought of the dangers her pre-teen children are undertaking as they swoop onto battlefields as leaders of a rebel resistance. Whether Karen will play a larger role later in the series remains to be seen.

The seventh book in the series is due out in 2016, and Kibuishi has indicated there will be nine books. My six-year-old daughter is already getting into them, and my four-year-old son should be ripe for them just about the time book seven hits the library shelf. They’ll be a bridge or a gateway, no doubt, in this household.

And for daddy here at the home front? Not a bridge or a gateway, but just more of the stuff he’s always loved.

Sounds delicious and potent. Thank you for the warning about the father’s death in the first pages — until that paragraph, I was about to race out and get a copy for a niece who lost her dad. Shouldn’t race. In a couple of years, when she starts wanting to process that loss through stories, this will be just the book for her.

My condolences to your niece — what a terrible loss. Another young-adult book to withhold for a couple years would be Neil Gaiman’s The Graveyard Book, which opens with the protagonists’ parents being murdered.

Come to think of it, another wonderful young-adult novel I read recently opens with the main character moving in with an eccentric uncle because he has lost his parents — John Bellairs’ The House with a Clock in Its Walls. Interesting to consider how many young-adult stories open with parental loss: relating to a point I addressed briefly above, the presence of protective parental figures can pose problems for adventure; and the sudden, jarring change in situation that must accompany such a loss is often used as a launching point for the protagonists’ adventures.

It’s actually hard to think of adventuring child characters who haven’t lost their parents. In The Chronicles of Narnia the children are parted from their parents by the war, and there are the Susan Cooper books, but otherwise there’s usually at least one parent who’s at least missing or in need of rescue, if not past all help.

The closest thing to YA I’ve written solves the parents-in-the-way problem by making them ghosts. They’re the protagonist’s constant companions, but their ability to rein her in is very limited. Also, she doesn’t always trust their advice on how to survive, since they haven’t. Their deaths propel her into adventure, and then they have ample opportunity to apologize for it.