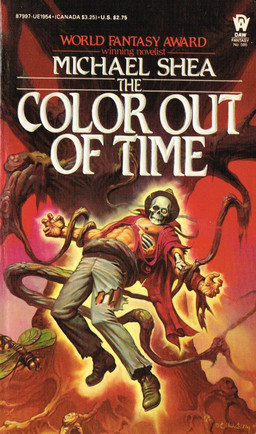

The Color Out of Time: Michael Shea Takes a Dip Into Lovecraftian Horror

I’ll mention this first about Michael Shea’s 1984 novel The Color Out of Time: the protagonists consume copious amounts of Wild Turkey. They fortify their coffee with it; they carry hip flasks full of it. This is a fact the narrator always notes casually in passing. Never are the potentially debilitating effects of alcohol mentioned; it simply occurs to the reader that these people might well be past the point of tipsy into “whiskey-river-take-my-mind” territory through much of the central action of the adventure. Perhaps that’s how they maintain their sanity. And make no mistake: sanity is but one of the possessions at stake for our heroes, because they have waded head-deep into Lovecraft territory. If they do manage to survive with their sanity intact, though, they might want to consider rehab.

I’ll mention this first about Michael Shea’s 1984 novel The Color Out of Time: the protagonists consume copious amounts of Wild Turkey. They fortify their coffee with it; they carry hip flasks full of it. This is a fact the narrator always notes casually in passing. Never are the potentially debilitating effects of alcohol mentioned; it simply occurs to the reader that these people might well be past the point of tipsy into “whiskey-river-take-my-mind” territory through much of the central action of the adventure. Perhaps that’s how they maintain their sanity. And make no mistake: sanity is but one of the possessions at stake for our heroes, because they have waded head-deep into Lovecraft territory. If they do manage to survive with their sanity intact, though, they might want to consider rehab.

The second thing I’ll mention is that because some of my own fictional excursions overlap with Shea’s foray into Lovecraftian horror — we tread similar unhallowed ground, digging up the bones of past masters of weird horror and coating them with fresh slime, if you will — I find myself contemplating the book not just as a critic, but as a writer: appreciating moves he makes while noting missteps and potential pitfalls. Ultimately, Shea’s sequel to H.P. Lovecraft’s 1927 short story “The Colour Out of Space” is entertaining, but slightly off, a tad unsatisfying, and I’ll try to pinpoint why — to isolate the juncture at which it diverges from Lovecraft’s vision and to articulate how this impacts the effectiveness of the tale. (For a different take on the book, check out Douglas Draa’s review for Black Gate last year HERE.)

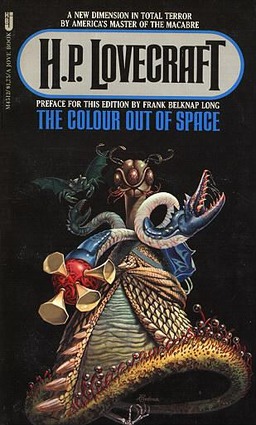

The premise is straightforward enough. Take the story that is generally regarded as Lovecraft’s first successful amalgam of science fiction and horror, a blend that became his unique trademark (“The Colour Out of Space” is one of Lovecraft’s most highly regarded and was always, according to Wikipedia, the author’s personal favorite. For the sake of full disclosure, it ranks high on my list of best horror stories and is one of my top two or three favorite works by Lovecraft). Start from the central event of that tale and then project its aftermath some sixty odd — very odd — years later.

In Lovecraft’s seminal story, the eponymous color comes to Earth via a meteorite that lands in a rural area near that infamous fictional city of Arkham, Massachusetts, a wild region that becomes known as the “blasted heath” and is later submerged by a new reservoir that thankfully buries the horror forever — or does it? When the rock from space is first located by the unlucky family whose farmland it struck, the meteorite’s strange properties quickly manifest. It is shrinking into nothingness, but leaving behind globules of a color outside anything seen in the human spectrum. These appear to have some will or volition, and they spread out into the land itself, with deleterious consequences to nature.

The mutations, which affect first the crops and wild vegetation and then the livestock and wild fauna, eventually manifest in the Gardner family, robbing them of vitality, of sanity, and ultimately of life, leaving only gray ash behind. The whole incident is eventually forgotten, except by one crazy old man named Ammi Pierce, a friend of Nahum Gardner’s who witnessed the events and serves to pass the tale along to the story’s narrator, a land surveyor trying to uncover the heath’s secrets before they are drowned forever beneath the waters of the reservoir. Needless to say, by story’s end the narrator is convinced never to drink any water sourced from that reservoir.

The final horrific fact related by Pierce is that when all the unearthly light appeared to purge itself from the Earth and shoot away into space — presumably having drained enough sustenance from our environment to continue on its implacable, inscrutable way — one tiny piece of it faltered and fell back to earth, back down into the well that is now a hole down there in the depths of the artificial lake.

The final horrific fact related by Pierce is that when all the unearthly light appeared to purge itself from the Earth and shoot away into space — presumably having drained enough sustenance from our environment to continue on its implacable, inscrutable way — one tiny piece of it faltered and fell back to earth, back down into the well that is now a hole down there in the depths of the artificial lake.

And that leaves an opening for an enterprising writer like Shea to wonder what became of that horrific lingering entity.

Things, of course, do not remain buried, and the entity has been having its slow effect in the ensuing years. A beach, docks, and campsite have been set up on the artificial lake, but few have noticed the strange mutations — because here is where Shea adds a new wrinkle. This entity is apparently conscious, calculating, and shrewd; it isolates its effects to areas of the forest where visitors generally do not go, leaving the recreational area untouched. For decades it has been gathering its strength, and the beach actually serves as a sort of food locker for it: plenty of vacationing humans all gathered conveniently together there on the edge of its wilderness hideaway until it is ready to feast.

The story is told an unspecified amount of time later by one of the two central protagonists, Dr. Gerald Sternbruck. He notes that he was fifty-nine at the time of the events, and his friend Dr. Ernst Carlsberg was “three-score and ten.” They are both old professors, which is nicely in keeping with Lovecraft and other masters like M.R. James — it is the scholars and academic explorers poking and prodding into the unknown who confront the horrors and come closest to comprehending the full implications of their existence. They like to spend some of their summer at the lake, drinking whiskey, smoking pipes, swimming, and aqualung diving — they are “both vigorous men” for their age, which they will need to be in their ensuing travails.

Shea’s protagonists — both the men and the woman who joins them — are people of action. They are smart, on the ball, capable if unlikely heroes. Refreshingly, they can quickly put two and two together and, even though the conclusions they draw are horrific enough that some people would either retreat into a state of denial or else be frozen into inaction by paralyzing fear, they are tireless in proceeding to do whatever needs to be done. With, of course, a fortifying belt of whiskey or two.

The two old friends are the first to notice the intimations of something amiss, and naturally they begin to investigate. Uncanny mutations on the lesser-used trails — like spiders the size of one’s hand — lead to the horrifying discovery of two park rangers who are displaying the unsettling symptoms so masterfully wrought in the original. Shea channels Lovecraft faithfully in his portrayal of the unnaturalness of these grotesqueries, of nature being bent all wrong by some alien pressure.

They soon find their way to the third protagonist, an elderly lady named Sharon Harms, who, as a girl, had been friends with one of the Gardner boys — the victims in Lovecraft’s original story — and who witnessed the horrific events along with her father. Her father presumably would have been Ammi Pierce, but here is where Shea makes another intriguing choice. Gerald, the narrator, reveals at this point in the plot that Lovecraft wrote the original story based on actual events, but changed the names and moved the timeline back to the 1880s, when in fact the horrors had occurred not long before Lovecraft fictionalized them.

It is a narrative move that brings Shea’s version of the story one step closer to “reality,” allowing him a little bit of meta-fictional commentary on the very fiction he is employing, when he reveals — not until page 82, mind you — that this is not truly a sequel to “The Colour Out of Space,” technically speaking, not at all. It is, rather, a follow-up to the events on which Lovecraft “based” his story, which exists as a work of fiction in the world of the novel we are in. This generates a subtle but significant shift in the reader’s frame of reference and perception of the novel.

As to whether this choice is wholly successful, I have mixed feelings — I’m not sure it was altogether necessary. It does allow Shea to have a bit of fun having his protagonists comment on Lovecraft’s work. Indeed, I will quote at length from Gerald’s own assessment after he has spent a day reading through Lovecraft’s stories for the first time (the second paragraph articulates Lovecraft’s especial proficiency for evoking the unknown quite accurately, and I imagine this summation pretty closely reflects Shea’s own opinion of the old master from Providence):

He combined a Ciceronian amplitude of style, a sonorous gentility of phrase, with an almost incantatory use of repetition and adumbration, which endowed the prose with a menacing, echosome quality. But precisely this excellence of artistry and effect disqualified the work as a source of vital empirical data that we urgently needed for our counter-assault on our vague, unspeakable enemy. And as for the tales’ substantial actions, they involved a pantheon of malign entities which had a similarly “invented” quality, their names clearly chosen for a threatening dissonance, or in an effort to produce a phonetic facsimile of certain names in established mythology.

But on the side of enthrallment was something both far more vague, and at the same time far more persuasive, than these considerations. For, as a pointillist’s technical strategy aims at an unreal idiom which, seen from the right distance, conveys new realities of light, so did Lovecraft’s narratives reveal, through an artificial idiom of fantasy, the true quality and meaning of the horror we had encountered. The precise psychological posture of that unique kind of dread, where awareness cringes from the first exploring touch, the first tenderly probing palpation of alien Entity, alien hunger — this was Lovecraft’s special preserve, and he fingered that web of stunning, reverberant horrors with matchless lucidity and resonance. 84-85

What is a bit harder to buy is the personal history that Sharon reveals she shared with Lovecraft. Sharon explains, “Maybe you’d say, if you felt psychological about it, that I took another father in Mr. Lovecraft. He was so generous. A man who loved to help you understand, with no interest at all in standing on his knowledge to make himself bigger than you” (146). We learn that Lovecraft actually took some part in defying and defending against these invading outside forces that he made famous — albeit in a shrouded and sensationalized way — through his fiction. Through Sharon’s knowledge, our heroes also learn that there are certain artifacts, objects of power, that can be and have been used to oppose these incursions by extra-dimensional entities.

For me, these machinations had the unfortunate side effect of conjuring up a more fantasized version of the Lovecraft Mythos — one more akin to traditional monsters and magicks, further from Lovecraft’s deliberate attempts to root his horrors in the cosmic unknown. Ironically, while the narrator makes note of how Lovecraft intentionally obscured the facts with “invented” qualities in his fiction, the more “true” version presented here seems much more fanciful than Lovecraft. That is the price of choosing to present the story as taking place in “our world” rather than in the world of Lovecraft’s story: my suspension of disbelief is more demanding and less forgiving in the former scenario, because the author has deliberately made it a point that the original stories are just “fictions” but that the horrors taking place in his book are, by contrast, the real thing.

Which brings us back to the monster. This is where I think I was probably most disappointed by Shea’s take on the original (and it parallels some of the criticism often leveled at August Derleth’s later adaptations): he takes something that was so wholly alien we cannot understand or comprehend it, and he makes it something that is evil. The entity here has a game plan; it patiently plots and manipulates — indeed, it seems capable of influencing the minds and actions of certain people, a parallel with the idea of demonic possession. But it becomes clear that the entity’s actions are not all rooted in a utilitarian aim to survive and eventually wrench itself free of its moorings to follow its precursors back to the stars. It clearly has an emotional aspect, too, insofar as it seems to derive pleasure — even sustenance — from human suffering and fear. Yes, it feeds on our fears, a common enough trope in horror fiction but one surprisingly absent in Lovecraft because Lovecraft knew that to assign such a motive to his monsters would be to give definition to them, diluting the effect of the unknown.

S.T. Joshi lauds this ambiguity in the original story, a big part of why he considers it one of Lovecraft’s most effective masterpieces. I don’t have Joshi’s original comments handy, but here is how they are paraphrased on Wikipedia: “Joshi praises the work as one of Lovecraft’s best and most frightening, particularly for the vagueness of the description of the story’s eponymous horror. He also lauded the work as Lovecraft’s most successful attempt to create something entirely outside of the human experience, as the creature’s motive (if any) is unknown and it is impossible to discern whether or not the ‘colour’ is emotional, moral, or even conscious.”

In Shea’s version, we can discern all three of those elements of the colour: it is conscious; it is emotional; it is moral, specifically, immoral — indeed, evil.

In modernizing the tale, Shea dropped the “u” from “colour,” but he also dropped the “u” of the “unknown.”

Lest we suspect Shea did not appreciate Lovecraft’s accomplishment in creating “something entirely outside of the human experience,” let me quote Gerald, the narrator, describing his feelings when he and his comrades set out on their boat for the final battle with the alien entity. This should dispel any notion that Shea just didn’t “get it”:

It was a sensation one might have if, walking in a public aquarium between bright tanks on a sunny Sunday, he suddenly found the light growing less, the tanks vaster, dimmer, with ever more gigantic submarine brutes swooping near the glass. The way steepens, and narrows, and the gay crowd grows haggard, dark, becomes a throng of mad-eyed, infernal victims, while immense multibrachiate shapes — shell-encrusted, big as ships — boil and writhe against the puny glass. 156

That is a truly haunting bit of prose; I get the creeps every time I spend a moment conjuring this analogy up in my imagination. It is worthy of Lovecraft at his best, invoking the unknown horrors lurking in the deep and using them as a metaphor for all that we do not know about the vast universe in which we so surprisingly find ourselves — not knowing how we came in, or why, or where we’re going when we go back out…or whether we should be terrified of the answers to any of those questions.

Yet this effect is somewhat undercut in the very next paragraph, when Gerald proclaims to his two compatriots, “I feel afraid…overtowered. By evil. An immense evil” (156).

So we know this about the entity: it gets some kind of pleasure from tormenting people both psychologically and physically. Some of these torments occur in ways that are quite gruesome, making the entity more evil but at the same time making it slightly less alien. You could substitute a Judeo-Christian version of a demon or the devil in the place of this extra-dimensional entity, and its actions might be pretty similar. It draws sustenance from human pain and suffering. Well, suddenly, we in some way comprehend it. We might not be able to relate to it, but we can understand it. We can infer that it tortures its victims because, on some level, it derives pleasure from that. And we can understand pleasure. We might derive our pleasure from baking pies and not from hurting puppies, but we can relate to pleasure.

In that one sense, I think the sequel veers from the source material. As Joshi and so many others have highlighted, in Lovecraft the motives of these horrifying things are incomprehensible to us. What do they want? Beyond human comprehension. Even try to make sense of it, and you might go insane. Here, though, as horrible and repugnant as the entity might be, we can comprehend it — in the same sense, for instance, that we can comprehend what drives a serial killer. Certainly we do not empathize with the killer; perhaps we cannot even imagine doing what he does without becoming nauseous. But if we understand that he derives some sort of pleasure from chopping up victims that is analogous, say, to the pleasure we derive from natural, consensual sex or creating a work of art or getting a promotion, then we glimpse in the inhuman one point we share in common: we both experience pleasure in the pursuit of something. The serial killer is a monster in that his ability to experience pleasure and reward has been twisted so as to be satisfied only by violent, murderous actions, yet that desire for pleasure remains, in and of itself, a common link of humanity.

And so, by accenting the alien monster’s perverse pleasure in its evilness here, Shea unintentionally makes it more knowable.

[SPOILERS AHEAD] The book climaxes in a horror of fairly large magnitude as the entity brings together dozens of its past victims from the depths of the lake and strings together an organic, living net of decaying human flesh: a monstrous, squid-like thing that can — horror of horrors! — thrust forth a specific corpse, perhaps the body of someone you knew personally, and then manipulate it like a marionette puppet…just for no other reason than to *%$& with your mind.

The ending is both triumphant and tragic. Dozens of vacationers die a nightmarish death, but at the same time the protagonists are able to defeat the creature, perhaps destroying it completely. Human ingenuity overcomes the alien threat — which, again, is another way of making that threat knowable, at least in knowing how to stop it. As soon as you know that you can stick a wooden stake through the heart of Dracula, Dracula is no longer quite so scary, is he?

The other thing I always wonder, with books like this that end just after the monster has been defeated, is, you know, what’s the aftermath? We know the narrator is recounting the story some months or years later, but in what context? After literally dozens of people just inexplicably died out there on the lake, what was the government response? What does the FBI make of the whole thing? Is there an ensuing government cover-up? There’s a whole other story that starts where many of these horror scenarios end, which tend to make interesting narratives when writers explore them.

But Shea concludes the tale when he does, giving some closure to the main action, and giving us a rollicking ride along the way. It is a story that, for the reasons I have enumerated here, I think could have been handled differently with slightly different results. I give the book 3.5 out of 5 stars, a rating that acknowledges that I enjoyed reading it and that I think it would be entertaining for other Lovecraft fans, although it’s not one that’s going to bowl you over — as Lovecraft so often manages to do. It’s a fun read, but ultimately a footnote, not a masterpiece like the story that inspired it.

RATING: 3.5 out of 5 stars

The Color Out of Time was published in 1984 by DAW under their “DAW Fantasy” imprint (it is DAW Book Collector’s Number 595). It had a cover price of $2.75. It is out of print, but a Kindle edition is available for $4.99.

I’ll have to reread this at some point. For me, the biggest flaw wasn’t that he made the monster evil — it was that he made the monster a monster; instead of a weird alien colour it turned out be kind of a giant spider thing.

Joe H.,

My take on the physical manifestation of the monster was that Shea was borrowing from the idea of John W. Campbell’s “Who Goes There?” (and its most famous adaptation, John Carpenter’s 1982 film The Thing): the “color” not only poisons and mutates organic matter, but can actually manipulate and possess it.

Yeah, I’ll have to reread it — it was years ago, and it’s possible I was missing something.

(And now I want to write the story of what happens when a major city on the eastern seaboard sends an aqueduct up into the hills …)

I read this one two or three years ago, and while I’m a big Shea fan, I was underwhelmed. It wasn’t terrible – I just didn’t think it was particularly compelling. I’m glad to see that I wasn’t hallucinating…