Living it Large: How Larger Than Life Characters Work

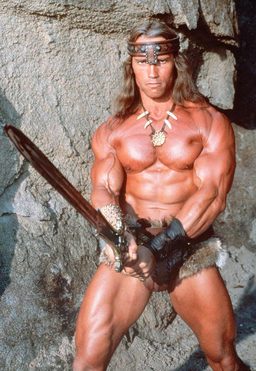

An extravagantly rich man who dresses up like a bat; space Jesus in skin tight spandex, shooting lasers out of his eyes; a big Austrian charging around in furry underwear and hitting things with a big sword.

An extravagantly rich man who dresses up like a bat; space Jesus in skin tight spandex, shooting lasers out of his eyes; a big Austrian charging around in furry underwear and hitting things with a big sword.

All of those individuals (and you know who they are) are examples of ‘larger than life characters.’ And such characters are at the center of what makes Sword and Sorcery what it is. These are creations that dominate their worlds, who capture our imaginations; these are characters that, for all their exuberance and strength, majesty and intellect, feel real. Their influence can be felt in every letter of every page. When done well, they’ll leap out of the page, wrap their hands around your throat and drag you along with them. They’re the guys who are at the center of it all, they’re the whole reason you’re reading the book. They’re not the host, they’re the main event.

But, at least conceptually, they shouldn’t be. These are characters that tend to be impossibly good at everything, who tend to be either extravagantly noble or impossibly evil; there is no middle ground when you’re dealing with larger than life characters. And this extremism make them a little difficult to relate to, and it’s relatable characters that are the most likeable, those that have the most impact, because it’s so easy to put yourself in their shoes. But larger than life characters, with their overblown motivations and rigid morals, don’t have that instant relatability.

Not only that, but larger than life characters (who I’ll refer to as LTLCs from now on) aren’t so much fully fledged characters as they are prototypes, often lacking depth, ambiguity, and complexity. By today’s standards, they’re nothing. Heck, these sorts of characters shouldn’t even be likeable; think about that one kid in class who, without fail, never missed an opportunity to flaunt his intelligence; he’s more likely to warrant a swift brick to the face than a warm pat on the back.

Yet, with all this, LTLCs tend to be pretty damn endearing: Marvel and DC make millions out of the guys; Robert E Howard created an entire sub-genre off the back of LTLCs, and western myths and legends are overflowing with the overachieving little guys. So it’s no secret that the characters are in demand. But, in the wake of all this, one has to ask: why are they so popular?

Well, I think it’s worth remembering that sometimes all we want is to see someone kick some serious butt, and not have to worry about stupid things like plot, character development, and world building. At this point, all the reader really needs is the slightest shred of context, and away you go. Larger than life characters, with their simplistic yet eccentric personalities, are a good way to achieve this without making your protagonist banal.

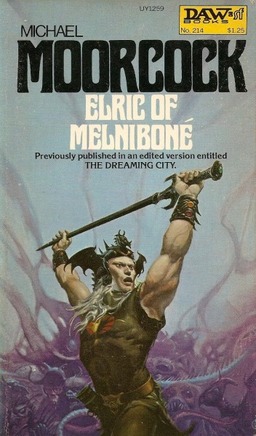

You don’t have to worry too much about developing the characters because their personalities are pretty much set in concrete and, so long as that’s solid, you’re good to go: Conan is a barbarian trying to make his way in society; he values honesty, strength, and boobs, but, ultimately, he’s in it for himself. Cool, not too complex, but not too boring. Elric is an albino; he’s reliant on Stormbringer to survive. Stormbringer takes advantage of this. Simple, but not banal. Having this middle ground allows the writer to focus on all the cool fun stuff, like creating the coolest monsters and pitting them against the hero in the coolest way possible. And butt-kicking. Don’t forget butt-kicking.

You don’t have to worry too much about developing the characters because their personalities are pretty much set in concrete and, so long as that’s solid, you’re good to go: Conan is a barbarian trying to make his way in society; he values honesty, strength, and boobs, but, ultimately, he’s in it for himself. Cool, not too complex, but not too boring. Elric is an albino; he’s reliant on Stormbringer to survive. Stormbringer takes advantage of this. Simple, but not banal. Having this middle ground allows the writer to focus on all the cool fun stuff, like creating the coolest monsters and pitting them against the hero in the coolest way possible. And butt-kicking. Don’t forget butt-kicking.

Make your character a blank slate whose only personality is ‘good guy’ and it’s hard to present the story as original, and there’s no reason why a reader should pick your story over the one with a more interesting character. And, besides, make a character with an actual personality and it’s much easier to craft a story that feels tailor-made for that character, as opposed to one copied from the ‘big book of generic plots.’

Another method of making them work is to give the reader a reason to keep reading, give them something interesting they’ll want to find out more about. This usually takes the form of some dark, tortured past that’s only ever hinted at (Waylander) or some grisly secret agenda, but that’s a horse that died a few decades ago. And you should never try to ride a dead horse, because its knee caps will explode. So then you have to find other, living, horses to flog.

Unpredictability is a nice, trusty steed (ironically); heck, that’s what kept me going through the slower portions of Bloodstone; simply reading on to find out how Kanes ‘master plan’ panned out, how he got from A to B, how he out-witted his victims. I wanted to see if it would work, when it would emerge or if it would fail.

It’s also present in the Elric tales, where I found myself wondering what role Stormbringer would play next, who he might betray, who he might aid; unpredictability keeps the reader guessing what might happen next and keeps them flicking pages for hours on end.

Unpredictability is what keeps kids up at night, hiding under the bed sheets with a flashlight and a novel until four in the morning. And, it works especially well with LTLCs because they have the kind of ostentatious personalities that make such a thing viable, personalities that make it believable. Slap a trait like unpredictability onto Vanilla Mcbland-face and it’s going to seem out of place, and it might just destroy all suspension of disbelief. And that’s not what you want in a fantasy. Not at all.

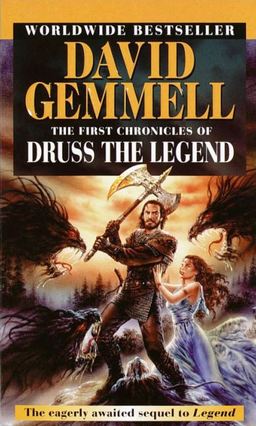

Or, you could take a good, hard look at some of the best LTLCs: Conan, Achilles, Elric, and Druss the Legend. You’ll probably find that most of them have some sort of weakness, some form of flaw: Conan harbors a fear of magic, Achilles has his heel, Beowulf his over-confidence, and Elric’s entire personality revolves around his weakness.

Then there’s Druss who’s kinda like the natural progression of LTLCs. On the surface, he’s your average hero, the kind of domineering, powerful personality you’d expect to find in the pages of a fantasy novel, but look past all that and he’s growing old, losing his sparkle: a fact that even he cannot accept, even as his back strains and arthritis starts taking its toll.

Then there’s Druss who’s kinda like the natural progression of LTLCs. On the surface, he’s your average hero, the kind of domineering, powerful personality you’d expect to find in the pages of a fantasy novel, but look past all that and he’s growing old, losing his sparkle: a fact that even he cannot accept, even as his back strains and arthritis starts taking its toll.

Druss has to maintain his persona for his men, to control morale, but his internal struggle humanizes him. To the public he’s a god: immortal and omnipotent, but behind closed doors he’s a human. There’s nothing more interesting, more emotional, then seeing a hero fail. Because a hero always seems immortal, unbeatable, and absolutely perfect, so watching a character you admire crumble is a genuinely touching experience.

But, aside from that, it also keeps the characters grounded and makes them all the more relatable. Everyone’s flawed, it’s a fact of life, and by giving a character flaws, the writer makes him or her human as opposed to some god-like entity, incapable of doing anything badly.

Without imperfections, LTLCs soon become very boring and, in some cases, lose plausibility. Take, for example, “Sword of the Hills,” an El Borak tale by Robert E Howard. The yarn itself is brilliant; it revels in the sheer lunacy and balls-to-the-wall action so often associated with pulp fiction. As a whole it’s glorious, self-indulgent fun.

But the hero is less so, he’s without any form of flaw, and his personality, motivations, and pretty much everything else about him can be summed up with ‘adventure story protagonist’ so, at least for me, he never really leapt out of the page, he never really came alive like Conan did. He’s half as interesting, half as memorable: El Borak wasn’t the living, breathing, human he should have been, he was just a character: a collection of words on a page. Nice words, sure. But just words.

An even worse mistake, however, is that of telling and not showing. That’s right, Dawnthief, I’m looking at you. As I mentioned in my review, Barclay (the author of the book) introduced us to the Raven: a group of absolutely useless mercenaries who do nothing but die, get wounded, and whine a lot. But Barclay, alongside the entire population of Balia (the setting), kept trying to tell me they were a group of unstoppable badass warriors fuelled by testosterone and liquidized awesome, which got more than a little irritating when they were smashed to bits for the umpteenth time.

I think the intention here was to make the Raven out as human, with flaws and weaknesses, or to pull a Druss, and make it seem that age was bogging them down. But the difference is that Druss wasn’t hopelessly incompetent, and, whilst his age made him human behind closed doors, when those doors were open, he was still awesome. When David Gemmel told me Druss was getting old, I believed him. When James Barclay said the same for the Raven, I thought he was making excuses.

It’s also smart to consider the fact that sword and sorcery specializes in pure, mindless escapism, and is at its best when it allows the reader to cast down the grimy chains of reality, slap a bucket on their head and charge off into the distance, screaming at the top of their lungs. It’s certainly what I read for. So one would think that this would give a writer a degree of freedom to make their world and its characters as crazy as possible, in an attempt to shred any links they may have to reality.

It’s also smart to consider the fact that sword and sorcery specializes in pure, mindless escapism, and is at its best when it allows the reader to cast down the grimy chains of reality, slap a bucket on their head and charge off into the distance, screaming at the top of their lungs. It’s certainly what I read for. So one would think that this would give a writer a degree of freedom to make their world and its characters as crazy as possible, in an attempt to shred any links they may have to reality.

And that’s true, up to a certain point (Moorcock’s multiverse certainly springs to mind). The hero has to remain somewhat grounded and approachable, especially in Sword and Sorcery, where he’s literally the center of everything — so if he’s utterly devoid of flaws, not only is he about as interesting as plastic, he’s also unrelatable.

But make them too normal and they’ll feel bland, like cardboard; they’ll be forgotten the second the book’s closed. It’s worth remembering here that heroes are memorable because they’re different, and that a character just like everyone else may be relatable, but they’ll also be very bloody boring.

It might also be an idea to give your characters something that actually makes them likeable, like a sense of humor, because otherwise they’re just big lumps of flesh, mingled with a bit of angst. Waylander has his dark, sardonic sense of humor, and, although he should be hateable, he never is, because of that. It’s worth remembering that the easiest way to connect with someone is to laugh at them.

In short, the hero of an S&S tale has to be interesting and different enough to be memorable, but flawed enough to feel real. It’s a difficult middle ground to attain, but one that’s always worth it.

So, I guess at the end of it all, LTLCs are just really cool tour guides; they make Moorcock’s mad bad multiverse accessible, they’ll show you around for a bit, let you see the sights and hear the sounds. At first, you might think that they’re beneath you, too simple for your sophisticated palate… and that’s when they grab you by the throat and drag you along with them. Before you know it you’re not being dragged anymore, you’re running along with them, and loving every second of it.

But, as ever, I might be entirely wrong, in which case feel free to call me nasty names and let me know why you think LTLCs work.

Love the post Connor! And I don’t think it’s by accident that you rely on two of David Gemmell’s characters to bolster your argument 🙂

Hi Jason!

Mylar you enjoyed it, and it was by no means an accident 😀 say what you want about gemmel but he’s definitely one of the best in the business when it comes to creating intresting heroes 🙂