Hope Among the Ruins

As I creep closer to the half-century mark, I find myself reflecting ever more often on my childhood. Though born at the tail end of the 1960s, I consider myself a child of the ’70s, since it was the images and obsessions of that decade that left the strongest impressions on my young imagination. I’ve mentioned before that popular culture in the 1970s was awash with the weird, the occult, and the apocalyptic. The latter saw its expression in the flowering of the “disaster movie” genre, which attained a kind of Golden Age in those days. Nowadays, the disaster films people most recall are fairly conventional ones, like Airport (1970), The Poseidon Adventure (1972), and The Towering Inferno (1974) – all of which I watched on network television after their theatrical releases – but the ones that had the greatest impact on me were those with a more global scope, like The Andromeda Strain (1971), The Omega Man (1971), and Meteor (1979). These were the motion pictures that fed my lifelong fascination with The End of the World as We Know It.

As I creep closer to the half-century mark, I find myself reflecting ever more often on my childhood. Though born at the tail end of the 1960s, I consider myself a child of the ’70s, since it was the images and obsessions of that decade that left the strongest impressions on my young imagination. I’ve mentioned before that popular culture in the 1970s was awash with the weird, the occult, and the apocalyptic. The latter saw its expression in the flowering of the “disaster movie” genre, which attained a kind of Golden Age in those days. Nowadays, the disaster films people most recall are fairly conventional ones, like Airport (1970), The Poseidon Adventure (1972), and The Towering Inferno (1974) – all of which I watched on network television after their theatrical releases – but the ones that had the greatest impact on me were those with a more global scope, like The Andromeda Strain (1971), The Omega Man (1971), and Meteor (1979). These were the motion pictures that fed my lifelong fascination with The End of the World as We Know It.

Growing up, I was possessed of the sense that life wasn’t necessarily as stable or as safe as it seemed to be on the surface. Real world events during the 1970s only made this point more forcefully. From the Energy Crisis to stagflation and fears of overpopulation and social unrest, life appeared awfully precarious in those days. And, of course, the ups and downs of relations between “the Free World” and the Soviet Bloc did little to suggest otherwise. Being a child, even a precocious one, I didn’t completely understand the full implications of a global thermonuclear war. I only knew that World War III (as my friends and I conceived it back then) was a virtual certainty, a belief reinforced by all manner of adults, from political commentators who publicly fretted about the implications of Ronald Reagan’s possible election in 1980 to my childhood idol, Carl Sagan, who regularly voiced his opinion that mankind was far more likely to destroy itself than to travel to other worlds.

Despite this, I can’t say that I was frightened by the prospects of the world’s end. Sure, I didn’t look forward to it, but I was just a kid and and I knew that, regardless of my feelings, there was nothing I could do to stave off Armageddon, so why worry? I’d read enough history by this point to realize that no world truly ends. Wars, plagues, and other sundry catastrophes were frequently devastating, marking the end of one era, but something almost always came afterwards. At my young age, I found it hard to countenance the possibility that even a nuclear war would spell the end of everything (despite that being the very reason why so many people lived in utter terror of it). I’d also read enough fantasy and science fiction to conclude that the End of the World might be adventuresome.

Dungeons & Dragons was, as it was for many young people of my generation, my introduction to roleplaying games. However, I didn’t play D&D exclusively for very long. Spurred by both the TSR Hobbies catalog included in my Basic Set – “Your Gateway to Adventure,” it proclaimed – and references to it in my AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide, I picked up my second RPG, the post-apocalyptic science fantasy Gamma World. Written by James M. Ward and Gary Jaquet, Gamma World took place in the 25th century, 150 years after a devastating event during which “oceans boiled, continents buckled, the skies blazed with the light of unbelievable energies.” The world that arose from the ashes was one in which

Dungeons & Dragons was, as it was for many young people of my generation, my introduction to roleplaying games. However, I didn’t play D&D exclusively for very long. Spurred by both the TSR Hobbies catalog included in my Basic Set – “Your Gateway to Adventure,” it proclaimed – and references to it in my AD&D Dungeon Masters Guide, I picked up my second RPG, the post-apocalyptic science fantasy Gamma World. Written by James M. Ward and Gary Jaquet, Gamma World took place in the 25th century, 150 years after a devastating event during which “oceans boiled, continents buckled, the skies blazed with the light of unbelievable energies.” The world that arose from the ashes was one in which

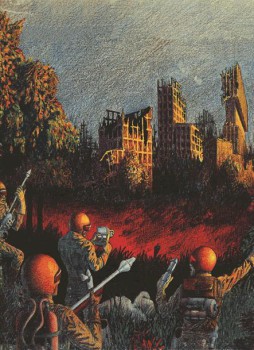

The ecological balance of nature was shattered as violently and as suddenly as man’s civilization. The sudden extinction of some species and the mutation of most others, coupled with the lack of man’s intervention and attention (except to his own survival needs), generated a near-worldwide wilderness inhabited by savage creatures who, like man, were struggling to survive.

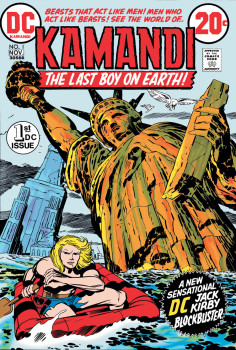

Filled with mutants, strange cults called “cryptic alliances,” insane robots, and other dangers, the future Earth described in Gamma World was a dangerous place, no doubt, but an exciting one, not dissimilar to the worlds described in Jack Kirby’s original Kamandi series for DC (1972-1978) or the Ruby-Spears cartoon Thundarr the Barbarian (1980-1982). In all of these post-apocalyptic visions, the place of humanity is uncertain, thanks to the fall of the old world and the rise of a new one hostile, or at least indifferent, to mankind.

Gamma World postulated that the human race would achieve great technological wonders – space travel, artificial intelligence, the harnessing of nigh-unlimited energy – and would then throw it all away in a fit of madness, in the process creating a world where the very survival of the species is in question. Yet, despite it all, mankind survives. As the game’s introduction puts it:

Through it all, the death, the pain, the horror, and facing the prospect of an unknown future, man searched for his lost knowledge, and struggled to regain his tools … to rebuild his self-destroyed civilization.

There’s a strange kind of hopefulness embodied in the above, one that I found particularly compelling in 1980, when I first stumbled across Gamma World. Rather than wallow in gloom and despair, Gamma World held out the possibility that men and women – with their mutant allies – might pick themselves up, dust themselves off, and venture into the ruins of the past to look for the means by which they could start the slow climb upward once again.

There’s a strange kind of hopefulness embodied in the above, one that I found particularly compelling in 1980, when I first stumbled across Gamma World. Rather than wallow in gloom and despair, Gamma World held out the possibility that men and women – with their mutant allies – might pick themselves up, dust themselves off, and venture into the ruins of the past to look for the means by which they could start the slow climb upward once again.

It’s frankly a brilliant set-up for a roleplaying game campaign. I’d even go so far as to say that it’s a better set-up than the default set-up for “vanilla” D&D, where the characters explore dungeons primarily for the sake of personal wealth and power. While I have little doubt that such motivations were common among Gamma World characters, too, there’s at least the possibility that they might have nobler motives, including a concern for the wider world.

I suppose I might be projecting my own feelings onto the game and, if so, it wouldn’t be the first time. In my Gamma World campaigns of old, the characters regularly worked for or were allied with a cryptic alliance called the “Restorationists,” whose ultimate goal was the rebuilding of civilization. Consequently, our adventures weren’t usually just smash ‘n grab operations intended to acquire loot, but concerted efforts to locate knowledge and devices that might improve the post-apocalyptic world. This was, of course, a never-ending struggle, but it was an exciting and worthy one that instilled in my friends and myself the sense that, while we might not be able to stave off the End of the World, we could work to pick up the pieces, should the worst come to pass.

Not a bad lesson to learn from a roleplaying game.

I love Gamma World! I still have my very-battered 1st edition boxed set (although the continental map went missing at some point over the years). It was one of the first two RPGs I ever got — my parents got me the D&D Basic Edition boxed set for Christmas, and also picked up Gamma World because (unlike the D&D set) it included the weird dice.

I stake out no position on gaming character motivation. I enjoy Fafhrd’s and the Gray Mouser’s personal enrichment just as much as Per Hiero Desteen’s efforts to restore civilization. Fun is fun, whether cloaked with altruism or not.

Well I remember the childhood certainty that the world would be destroyed by nuclear weapons before I ever reached adulthood. For people who grew up in the DC area, this certainty was especially inescapable. It’s hard to explain to my students what that was like. I’m so glad, for their sake, that they have no firsthand experience of it. I remember being especially drawn to science fiction that explored ways of surviving the unsurvivable.

[…] World ( Black Gate) Hope Among the Ruins – “In my Gamma World campaigns of old, the characters regularly worked for or were […]

@Sarah

Yes, it’s hard to explain to someone that didn’t live through it what it was like during the zenith of the Cold War. It was so in the atmosphere at the time, including movies like Mad Max, The Road Warrior, Robocop, etc. And I can remember being deeply affected by the made for TV movie The Day After–very depressing.

One anecdote: I can remember being around 11 or 12 (1980 or 1981) helping my dad in our small backyard garden. At one point a military helicopter flew by (this wasn’t uncommon where I lived). Then my dad said to me in a very serious tone: “I hope you never have to hear that and run.”

There was just this kind of scary tension behind every thing back then. I think pop culture (including games like Gamma World were ways to deal with it and stay sane.

I was just discussing classic Gamma World elsewhere on the Web.

I loved that game, and I didn’t play it nearly enough. I think it appealed to me even more than D&D – perhaps because, as others have noted, post-(nuclear)-apocalypse was in my blood as a child of the Cold War and an original ApeHead (Planet of the Apes.) I was more familiar with scifi at the time and the only fantasy I was exposed to was Lord of the Rings.

And then this popped up on Amazon the other day – coming in June.

DC Showcase Presents The Great Disaster

http://www.amazon.com/dp/1401242901/ref=wl_it_dp_o_pC_nS_ttl?_encoding=UTF8&colid=3MEPLDIHXLFUF&coliid=IPAJFUF8MOHPK

I’ll be buying it.

See? Even after all this time I still have a weak spot for those kind of tales.

James, your posts have a tendency to make me wistful for some very fun times. Gamma World was a fun (and usually goofy) respite from the more “serious” matters at hand in our D&D sessions.

A vastly under-appreciated variant on the apocalyptic novel was Frank Herbert’s ‘The White Plague.’ In its way, I hold it on a par with ‘Dune.’

[…] Hope Among the Ruins […]