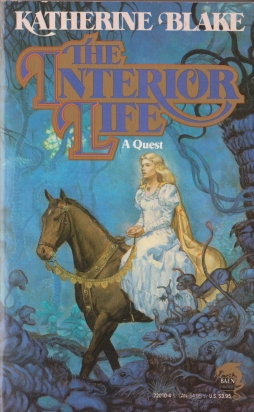

Katherine Blake (or Dorothy Heydt) and The Interior Life

I’ve mentioned a few times before that I have a fascination with 80s fantasy, and suspect a number of now-overlooked genre books from those years are worth closer examination. I want to put forward another example of what I mean: The Interior Life, written by Dorothy Heydt under the name Katherine Blake. Published in 1990, it’s a novel that does interesting things in mixing a fantasy world with the experiences of a modern-day housewife.

I’ve mentioned a few times before that I have a fascination with 80s fantasy, and suspect a number of now-overlooked genre books from those years are worth closer examination. I want to put forward another example of what I mean: The Interior Life, written by Dorothy Heydt under the name Katherine Blake. Published in 1990, it’s a novel that does interesting things in mixing a fantasy world with the experiences of a modern-day housewife.

The book starts with Sue, whose three kids have just started the school year. Sue’s doing some daily chores and remembers how she told herself fairy tales when she was a child, creating and inhabiting fictional characters: “all the people I used to be.” After which, she starts seeing the lives of people in the quasi-medieval world of Demoura. More precisely, she sees things from the perspective of Lady Amalia, a noblewoman with magical gifts, Marianella, her maid, and occasionally others such as Kieran, an innkeeper’s son who joins Amalia’s service. Demoura’s menaced by a Darkness creeping westward across the land, blighting all in its path; the characters of the Demouran story live a fairly conventional high fantasy tale of an evil wounding the land, of the struggle to overthrow the dark and bring healing. But those characters also, as the story goes on, provide inspiration for Sue.

You could in theory read the book as moving back and forth between two separate worlds. Heydt, in the comments to this perceptive review of the book by Jo Walton, has said that she thinks of the fantasy aspects as entirely Sue’s creation; in fact, without being explicit, a number of things about the set-up imply this. It’s subtly done. Notably, the life-and-death drama of the fantasy becomes the venue for Sue’s development as a person. She wants nothing more than to tend her family — raise her kids and cook and keep house and help her husband advance in his career. However old-fashioned this sounds, the novel makes it clear she’s happy with this life, and the point of the book is not that she finds new goals, but that she becomes better at what she does and happier in the course of doing so. Two or three interesting points come out of this. First, the blending of the ‘real’ and ‘fantasy’ worlds is worth considering, well-done and unusual. Second, the book points out a generic similarity in fantasy stories about a protagonist developing skills and learning to master their world. Three, and this is perhaps more marked from a twenty-first century perspective than a 1990 perspective, it raises some interesting questions about what is contemporary and what is archaic. Sue’s life and aspirations feel dated in ways that the fantasy of Demoura does not.

A word about Heydt before going on. Active in sf fandom, she conceived and edited the original Star Trek Concordance in 1969. The Interior Life was her first novel. Her second, A Point of Honor, followed in 1998. She’s also written many short stories, or series of short stories, published in venues including some of the Sword and Sorceress anthologies; you can find a list here.

A word about Heydt before going on. Active in sf fandom, she conceived and edited the original Star Trek Concordance in 1969. The Interior Life was her first novel. Her second, A Point of Honor, followed in 1998. She’s also written many short stories, or series of short stories, published in venues including some of the Sword and Sorceress anthologies; you can find a list here.

The Interior Life uses subtly-different typefaces to represent the different characters and worlds. Heydt’s expressed dissatisfaction with the choices of fonts, intending the distinction to be more immediately obvious. At any rate, the book moves easily between this world and Demoura, with transitions sometimes happening within a paragraph. Events usually run in parallel; the first chapter, for example, alternates between Sue cleaning house and Marianella cleaning up an abandoned fortress. Sometimes an image in one world resonates in another, serving as a kind of bridge.

There’s no explicit statement in the book that Sue creates Demoura, but the implication is strong, given that it emerges after Sue remembers how she used to create fantasy worlds. She visualises Demoura as a separate reality, and the characters there don’t seem aware of her, for the most part. Or, at least, not as they live out their principal story, struggling against the Darkness as Sue watches through the perspectives of the individual characters. But then also other things happen as well, and the relation of Sue to Demoura becomes intriguingly complicated.

There’s a kind of third space in Sue’s head, as though it were between worlds, in which she speaks with the Demouran characters and they advise her in how to live her life. The quasi-medieval Demouran world provides good sense and life lessons for the contemporary world, helping Sue become better at the crafts she chooses to master. The Demourans bring their own knowledges and awarenesses to bear on her problems, but don’t seem to remember her as they live their own tale. It’s a kind of alternate story, if you like, a fork in the narrative. It’s a representation of a creator speaking with the characters who live inside the head; and the surprising insight those characters can have, insight seemingly separate from that of their creator.

There’s a kind of third space in Sue’s head, as though it were between worlds, in which she speaks with the Demouran characters and they advise her in how to live her life. The quasi-medieval Demouran world provides good sense and life lessons for the contemporary world, helping Sue become better at the crafts she chooses to master. The Demourans bring their own knowledges and awarenesses to bear on her problems, but don’t seem to remember her as they live their own tale. It’s a kind of alternate story, if you like, a fork in the narrative. It’s a representation of a creator speaking with the characters who live inside the head; and the surprising insight those characters can have, insight seemingly separate from that of their creator.

(There’s a story I heard once about a man paying a visit to a friend who was a puppeteer — I think it was Bob Smith, who voiced Howdy Doody [later edit: nope, it was Edgar Bergen, who voiced Charlie McCarthy]. The story has it that a window was open and as the friend got to the front door he heard the puppeteer inside the house speaking intently to the puppet about Deep Things, up to and including the meaning of life. The friend knocked and went in, and asked the puppeteer what was happening. The puppeteer admitted he often talked about these sorts of things with the puppet. “But he’s not real,” exclaimed the friend. “I know,” said the puppeteer, “but he gives such great advice.”)

Sue herself is able to pick out elements in this world — an actor’s face, a Pre-Raphaelite painting — reminiscent of something in Demoura. That sounds right: the artist finds elements in the reality around them that seems to buttress the secondary reality they imagine. There’s another instance where a someone in this world might have seen a character from Demoura, but that’s very much an open question. At that moment you could say that Sue’s interpreting a chance comment in a way that’s important to her, that her fantasy’s gripped her so she finds meaning in things with no objective relation to her imagining. Or you could say that she’s instinctively taking the matter of the world around her as grist for the fiction she’s creating. Or that a certain kind of meaningful coincidence exists, or comes to be visible, in which the outside world supports the inner imaginings. Or simply that the fiction bleeds through to reality. Or that all these things are happening. The point is that the relation between creator and created is not simple. There’s one point where one Demouran character echoes a thought of Sue’s, and another where she’s able to pass a mental message along to a Demouran; so Sue makes herself a character in the fiction she imagines.

That said, Demoura’s not the most believable of worlds. The characters don’t always behave credibly, and neither they nor the enemy they fight seem particularly deep. But maybe it’s supposed to be the kind of fantasy world that someone who has talent but no experience would create. If sexuality in Demoura seems unlikely (not much concern about pregnancy or contraception, for example), you can also say that this is Sue working out her own sexual desires; and, generally, the this-world parts of the book are frank without being over-detailed about Sue’s sexuality and physicality.

That said, Demoura’s not the most believable of worlds. The characters don’t always behave credibly, and neither they nor the enemy they fight seem particularly deep. But maybe it’s supposed to be the kind of fantasy world that someone who has talent but no experience would create. If sexuality in Demoura seems unlikely (not much concern about pregnancy or contraception, for example), you can also say that this is Sue working out her own sexual desires; and, generally, the this-world parts of the book are frank without being over-detailed about Sue’s sexuality and physicality.

In fact there’s generally a kind of unobtrusive clarity to the style that serves the book quite well. It doesn’t try to be ‘elevated,’ simply focussing on a precision of descriptions and sense-detail. Here’s a quote from near the end, moving from a magic place in Demoura to a garden Sue’s planted in her front yard:

In the House of the Mists spring never came. The days grew longer, and the sun rose higher each day over the House and the frozen valley. Sometimes a few drops of water fell from the stone lintels, and spattered on the steps. Sometimes in the depth of a cold, clear night, thin sprays of ice crystals would form along the stony walls and floor. Nothing else grew, and there was no green by day, only by night an emerald star that peered over the rim of the Shadow like a wildcat’s eye, every night a little higher.

In the back yard, the grass was springing back, and Sue had a row of lettuces and two rows of bush beans planted. Every Saturday she dug up a few more feet. A length of tall wire fence was on her shopping list, to keep the kids’ playground separate from the vegetables and to give the peas something to climb on.

Each scene is sharply described, and gains by the contrast of one against the other. It’s notable that Sue’s depicted here as it were in motion, making plans and carrying them out. Part of the trajectory of the book is Sue’s development from a passive character to an active one — albeit active within what would from the outside seem to be a narrow sphere.

But what I want to point out in this quote is that the style doesn’t shift between the worlds. The language is the same, though the atmosphere of the two scenes is quite different. The diction unifies the worlds. More than that, the specificity of detail elevates the ‘real’ world. There’s something of a tradition in fantasy writing, I think, to give elaborate descriptions of objets d’art and highly-worked settings or weapons or other implements that move the story along. That sensitivity to the beauty of things is applied here to the real world, in brief but oddly intent descriptions of a piece of jewelry Sue picks out to wear or a high-quality raincoat she finds for a surprisingly good price. Clear descriptions are an element of good prose, but I find that the way Demoura’s written and its juxtaposition with Sue’s life means that passages which otherwise would read like realist fiction instead are situated within a tradition of fantasy writing. The vision of this world becomes the same as the vision of the fantasy world.

But what I want to point out in this quote is that the style doesn’t shift between the worlds. The language is the same, though the atmosphere of the two scenes is quite different. The diction unifies the worlds. More than that, the specificity of detail elevates the ‘real’ world. There’s something of a tradition in fantasy writing, I think, to give elaborate descriptions of objets d’art and highly-worked settings or weapons or other implements that move the story along. That sensitivity to the beauty of things is applied here to the real world, in brief but oddly intent descriptions of a piece of jewelry Sue picks out to wear or a high-quality raincoat she finds for a surprisingly good price. Clear descriptions are an element of good prose, but I find that the way Demoura’s written and its juxtaposition with Sue’s life means that passages which otherwise would read like realist fiction instead are situated within a tradition of fantasy writing. The vision of this world becomes the same as the vision of the fantasy world.

Inside the story, too, Demoura seems to become a source of meaning for the earthly world. As a reflection of Sue’s life it heightens her emotional experiences. The ‘interior life’ is a term from Catholic devotional literature, referring so far as I can see to a turning away from the external life to the internal world of the soul. Here it refers to Sue’s fantasy life, but that life is inextricable from the exterior life. The two lives are one, and support each other. It’s notable that Sue makes a distinction between Demoura and other, external, fantasies; when, encouraged by her characters, she plans to attend a PTA meeting for the first time, she compares it to a “kind of Flash Gordon/Indiana Jones adventure.”

It’s notable that Demoura’s the only source of real drama in the book. The Demouran characters’ battle against Darkness doesn’t seem to have an earthly parallel. Instead, the interest in Sue’s life comes from watching her gradually grow more confident and more able to do the things she wants to do. Her crafts are domestic — cooking, cleaning, decorating — but she learns to do them better thanks to her experience, or imagining, of Demoura.

And this is the second point I wanted to make about the book: Sue’s ‘levelling up’ is exactly parallel to the slow development of the hero one often gets in genre fantasy. That is, her learning to be a better housewife is structurally parallel to the typical fantasy hero or heroine learning to become a better warrior or wizard. And there’s a level of interest for the reader in her development, her increasing ability to manipulate the externalities of her life thanks to her internal growth, just as there is in watching the usual protagonist become better at whatever special talent they need for their story.

And this is the second point I wanted to make about the book: Sue’s ‘levelling up’ is exactly parallel to the slow development of the hero one often gets in genre fantasy. That is, her learning to be a better housewife is structurally parallel to the typical fantasy hero or heroine learning to become a better warrior or wizard. And there’s a level of interest for the reader in her development, her increasing ability to manipulate the externalities of her life thanks to her internal growth, just as there is in watching the usual protagonist become better at whatever special talent they need for their story.

There’s an argument to be made that Sue’s development is excessive, and too easy. Nothing seems to impede her growth (and her experience of Demoura does lead her to educate herself about history, art, and classical music). A scene where she counsels a battered wife is facile, with Sue always guessing right about the woman’s experiences. Ultimately this excessive ease tends to devalue Sue’s growth, suggesting that there was, after all, nothing in her way in the first place.

It also has to be said that some of the decisions Sue makes are baffling, if not disquieting. Sue learns to host parties to help her husband impress his boss and get a better job, but when the boss hits on her, promising to give her husband the promotion, she doesn’t at first tell her husband what the boss did. There’s generally not much communication between the two, which is a little disquieting given that we’re expected to view their relationship as a happy marriage.

But I wonder how much I’m projecting my own expectations back onto a past generation. Which brings me to the third point: the book leads you to question what is modern and what is antiquated.

But I wonder how much I’m projecting my own expectations back onto a past generation. Which brings me to the third point: the book leads you to question what is modern and what is antiquated.

Before elaborating, I should note that some things about the book struck me as old-fashioned even for 1990. Sue’s unquestioning acceptance of her role as homemaker, for example — at one point she even thinks to herself that “there was a time I thought day care was unnecessary because any proper mother would be at home all day!” Even given that she’s moved beyond that thought, it’s a little surprising to me that a woman apparently about thirty in 1990 would have accepted this. And surprising that she’d choose to be a housewife so completely and so certainly; Sue has no real doubts about her path in life, no desire for a career or calling. I can imagine some readers having a problem with the fact that her dedication to her family seems to be the sole source of external meaning in her life.

But the same slightly out-of-date feel is also present, if slightly less obvious, in the depiction of her husband’s life. He’s described as working for a corporation where men grow old at the same job. He himself appears to expect to maintain his job indefinitely. I turned 17 in 1990, and so am not exactly of his generation, but certainly it seemed to me and friends my age that careers didn’t have that sort of shape; as I recall, we knew we’d almost certainly be moving around. In fact, the whole set-up of the man at work jockeying for a promotion while his wife learns to be a perfect homemaker feels more antiquated than anything in the pseudo-medieval fantasy world. Which may be the point.

I don’t know whether the book was written some time well in advance of its publishing date. The technology’s right for 1990 — CD players are around but still new, Sue’s husband learns to use an IBM PS/2 computer. But those references could have been added in a pass before editing. Structurally, part of Sue’s growth comes from her helping to convince the PTA to build a new computer lab instead of a gym; in the course of doing this, she has to point out to other PTA members that computers will be an important part of their children’s future. Was that right for 1990? I can’t remember. I’m looking back on these things now from a distance.

I don’t know whether the book was written some time well in advance of its publishing date. The technology’s right for 1990 — CD players are around but still new, Sue’s husband learns to use an IBM PS/2 computer. But those references could have been added in a pass before editing. Structurally, part of Sue’s growth comes from her helping to convince the PTA to build a new computer lab instead of a gym; in the course of doing this, she has to point out to other PTA members that computers will be an important part of their children’s future. Was that right for 1990? I can’t remember. I’m looking back on these things now from a distance.

Which is what I mean about the book pointing out what is archaic and what is really contemporary. You can’t help but think that the role given to Sue for her life is a holdover from eras past. A man met in passing at a party speculates about biology versus history, but the effect of the book is to make you realise how much of modern life is similar to the daily life of the past: how cooking, and cleaning, and sewing, and addressing people you meet, are fundamentally the same skills as they were ages past. How social roles have changed; and how they haven’t.

If the book itself doesn’t seem interested in turning into a meditation on history, I still found it had a tendency to provoke that meditation in me as a reader. And I found it illuminated the way people lived and thought in a past era — not the era of knights and castles and crusades, but the era in which women were expected to stay home with their children while men worked at a single job their whole life. From that perspective, Sue’s happiness and ability to find meaning in her family is fascinating. Reading a book like Ursula Le Guin’s Always Coming Home, one finds an imagined society in which everyone works at simple crafts and creates simple arts with no obvious interest in making masterpieces; and, for me at least, that can be difficult to relate to. Looking at Sue’s life, her satisfaction in keeping house, helps to make that vision more understandable. The Interior Life has something to say about the importance of the interior life for its own sake.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.