You got your Zombies in my Pride and Prejudice!

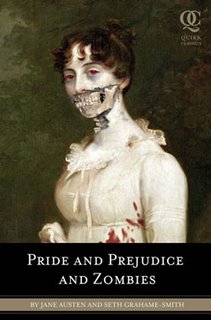

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies

By Jane Austen and Seth Grahame-Smith (Quirk Classics, 2009)

I love the genre of “re-contextualizing,” taking a work of art, regardless of its qualities, and slamming it into a new setting to see what happens. This can come from a Warholian perspective, or it can be done with the humorous ocean of pop-culture parody in Mystery Science Theater 3000 (which I have no hesitation in naming my favorite television show ever). Re-contextualization can be as simple as re-writing the captions for The Family Circus and printing Garfield cartoons with Garfield’s thought-balloons removed to create a surreal world. It can also create a new work of art, such as taking Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov’s aria “The Song of the Indian Guest” from the opera Sadko and making it a jazz classic like “Song of India,” perhaps one of the greatest dance-pieces ever charted.

Although re-contextualizing often implies satire or parody, it can simply involve experiment. “What would such-and-such feel like if it were altered in a certain way? I think it would go something like this. . . .”

And that’s where the new volume Pride and Prejudice and Zombies comes in. Author Seth Grahame-Smith, who wrote The Big Book of Porn, a look into the oddest entertainment industry, and How to Survive a Horror Movie, takes the text of Jane Austen’s 1813 comedy of manners and tweaks it to include a zombie plague overrunning the English countryside at the same time that busybody Mrs. Bennet maneuvers to get her daughters married to eligible bachelors.

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies looks like a snarky joke—and the marketing for it emphasizes this. Grahame-Smith’s rationale for committing this act of revising (some folks would say blaspheming) a literary classic with modern horror conventions is that he thought it would be really funny. And it often is. But, as I’ll later explain, I ended up with a much different sensation from reading the enterprise than a gory joke juxtaposed with prim English manners. As jokes go, the last laugh may be on Seth Grahame-Smith.

Admission of bias: I’m not a Jane Austen fan. I don’t generally enjoy mainstream classics or Regency literature that don’t involve the overtly Gothic. But I did re-read Pride and Prejudice in preparation for Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, and you can read some of my thoughts on that re-read here.

On to the successes and failures of Pride and Prejudice and Zombies. . . .

England has suffered under “the strange plague” of the living dead outbreak for a number of decades, and the Bennets have holed up in the countryside to defend their estate from the zombies (usually called, much more urbanely, as “unmentionables” and “the stricken”). Mrs. Bennet, true to her character in the original, has turned to trivialities of life to keep herself occupied, which annoys Mr. Bennet to no end. “The business of Mr. Bennet’s life was to keep his daughters alive. The business of Mrs. Bennet’s life was to get them married.”

Elizabeth is the most capable of the Bennet girls: “Lizzy has something more quickness of the killer instinct than her sisters.” Which means she has more anti-zombie martial arts training from Kyoto and Beijing, handles a musket and katana blade expertly, and takes the plague seriously.

Just as with Austen’s original, the story begins when Mr. Bingley, single and eminently marriable, moves into a nearby estate (zombies slaughtered and ate the previous tenants), and Mrs. Bennet can’t wait to parade her daughters before him. The eldest, Jane, gets her best opportunity when a zombie ambush on the road gets her bed-ridden at Bingley’s estate. Elizabeth and her two younger sisters, who have more interest in the soldiers of the regiment who are stationed in the countryside to burn coffins and crypts, ride out to attend to Jane in the hopes she hasn’t caught the deadly plague. This section is one of Grahame-Smith’s more clever adaptations of a situation from Austen’s novel that doesn’t make itself too obtrusive.

The odious Mr. Collins, on whom the Bennet estate will entail, makes his entrance. His patron, Lady Catherine de Bourgh, will make a different sort of impression in the revised novel as one of the most fearsome zombie-slayers in England. Elizabeth’s dislike of Mr. Collins stems equally from his insufferable sense of entitlement as from his cowardly attitude toward the unmentionables; he thinks a good word will do better than decapitation with a Chinese blade, while Elizabeth knows differently. But Mr. Bingley’s friend, Mr. Darcy, starts to prove his mettle to Elizabeth when he cleans up a zombie infestation that eats some of Mr. Bingley’s servants at Netherfield (“Mr. Bingley observed the desserts his poor servants had been attending to at the time of their demise—a delightful array of tarts, exotic fruits, and pies, sadly soiled by blood and brains, and thus unusable.”)

The story continues much as we know it, with Elizabeth rejecting Mr. Collins’s suit, and then Mr. Darcy’s, only to later discover some rather surprising aspects about Mr. Darcy that will lead to inevitable love. Except there are occasional zombie raids, and Elizabeth has to solve situations more than once with aerial martial arts and a swinging blade—which includes her meetings with Mr. Darcy. Rejection of a suit in Pride and Prejudice and Zombies can have deadly consequences.

I could come up with numerous comparisons to show how Grahame-Smith alters the original with new genre content, but I think a more instructive example shows how he shears some of Jane Austen’s text (presumably to fit in more undead and martial arts action). From Chapter 25:

“I hope,” added Mrs. Gardiner, “that no consideration with regard to this young man will influence her. We live in so different a part of town, all our connections are so different, and, as you well know, we go out so little, that it is very improbable that they should meet at all, unless he really comes to see her.”

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies pares this down:

“I hope,” added Mrs. Gardiner, “that no consideration with regard to this young man will influence her. We go out so little, that it is very improbable that they should meet at all, unless he comes to see her.”

As a Reader’s Digest Condensed Books version, that’s not bad.

The posthumous collaboration works best when the horror angle stays a subtle part of the daily lives of Austen’s characters; that is, when Austen’s prose stays at the forefront. Chapter 3 has the first explosion of a zombie horror that has no real connection to anything in Austen. Zombies attack a ball right as Elizabeth is having her first dealings with the proud Mr. Darcy:

Unmentionables poured in, their movements clumsy yet swift; their burial clothing in a range of untidiness. Some wore gowns so tattered as to render them scandalous; other [sic] wore suits so filthy that one would assume they were assembled from little more than dirt and dried blood. Their flesh was in varying degrees of putrefaction; the freshly stricken were slightly green and pliant, whereas the longer dead were grey and brittle—their eyes and tongues long since turned to dust, and their lips pulled back into everlasting skeletal smiles

As an imitation of Regency prose style and manners, this works. I especially like the nod toward “decency” in the zombies’ dress. But as a story intrusion, and even more so the Bennet girl’s martial display to destroy the ball-crashers, it feels more artificial than other places where Grahame-Smith sneakily introduces the plague into the established attitudes of Austen’s very decorum-minded characters, where it is both funny and makes a degree of sense with the style and period. (For example, the Bennet girls go armed on trips at night to visit other estates and attend balls, but only with knives because carrying around muskets is “unladylike.” I think this got the biggest laugh from me in the whole book.) In places, the co-writer pushes too far beyond what is believable even for the outrageous situation, such as Lizzy ripping out a vanquished ninja’s heart and eating it, then commenting on its tenderness.

Grahame-Smith does manage some interesting interpolated sequences, such as an encounter with a zombie infant, and the way that he excuses Charlotte Lucas’s decision to marry the unpleasant Mr. Collins after Elizabeth rejects his suit—this even caught me off-guard. Mr. Darcy has legitimate reasons for warning Mr. Bingley away from marriage to Jane Bennet, and even Elizabeth has to admit that perhaps her desire to slit Mr. Darcy’s throat was a touch extreme.

But long stretches remain Austen almost entirely, except for some slimming down and Elizabeth occasionally mentioning her Shaolin training and threatening to kill someone for dishonoring her. I can hear Grahame-Smith at his computer with Austen’s text in front of him, thinking, “Crap, no zombie mentions for a whole page. I’ve got to wedge something in here.” Sometimes it works—I do enjoy the idea that Elizabeth gets so tired of Lydia prattling that she fantasizes about chopping her head clean-off. But often it sounds forced.

The Asian martial-arts angle is the clumsiest of the revisions; while I can see the English countryside politely—but firmly—reacting against a living dead contagion, the inclusion of Eastern fighting techniques strikes false every time it comes up, and doesn’t seem to fit the Bennet sisters at all. Strong women, yes (well, maybe not Lydia), but running off to Beijing and Kyoto for extensive training in Eastern fighting techniques and philosophy? Nope. But Lady Catherine, Austen’s social villainess, now is a fearsome zombie killer with her own army of ninjas, and it isn’t a bad transition.

Grahame-Smith also has trouble wedging in specific detail about the plague and the social changes that England has undergone. We get a brief glimpse of a siege-minded London, and a glance at the people who burn the zombies for a vocation, but it feels as if the collaborator didn’t know where to insert the background material, and thus left most of it out. The plague feels hasty and unreal; the world-building we would expect from a modern novel simply never emerges.

Pride and Prejudice and Zombies loses momentum around the middle, and I will lay most of the blame on Austen for this, although if Grahame-Smith needed to punch up any section, this is it. I found my attention flagging between Elizabeth’s rejection of Mr. Darcy’s suit and Lydia’s elopement (or kidnapping), and that’s the same place where I lost my attention span in the original.

The novel concludes with a “Study Guide,” which makes a nice parody of the type of dry questions some publishers now feel they have to cram into the back of volumes of classics so people at book discussion groups will all ask the same boring questions. I especially like question #7: “Does Mrs. Bennet have a single redeeming quality?” I think she does, but doubtless many high school readers would have answered with a booming “no.”

The back cover blurb pays a backhanded compliment to Miss Austen’s original: “[the book] transforms a masterpiece of world literature into something you’d actually want to read.” Since millions of people read and enjoy Pride and Prejudice to this day, this remark speaks directly to genre fans who would never pick up Austen’s novel even at musket-point. But they aren’t likely to enjoy this book that much, despite the blurb’s claim and the book’s marketing strategy. The people who I think will most enjoy it are (drum roll please . . .) Jane Austen fans!

And that’s the major surprise for me. The strangest compliment I can pay to Pride and Prejudice and Zombies is that it increased my appreciation for Jane Austen, never an author for whom I have had much affection—although that might have more to do with a flood of genteel film adaptations in the 1990s that put me to sleep. Re-reading Pride and Prejudice for the first time since high school to prepare me for this book only gave me a modest boost in my impression of Austen; her wit and characterizations impressed me, the book didn’t involve me beyond a superficial level, and my attention tended to wander while reading. But observing this modernist take hurl a George Romero zombie apocalypse into Austen’s polite Regency world, and then seeing Miss Austen’s story and prose absorb it all without losing the essential quality of its characters and themes, made me understand why she has survived so long as such a popular—nay, mainstream bestselling—author to this day, and the center of a devoted fanbase.

And to this fanbase I think the book will speak the clearest. Jane Austen fans with a sense of humor will probably love it. (A certain core will hate it, but they know who they are and won’t bother reading it.) People such as myself, who enjoy irony and re-contextualizing, will also find a lot to analyze and enjoy, even though the joke does wear thin at three hundred-plus pages. It may offer readers a renewed understanding of a classic. The only people who won’t enjoy the book are hardcore horror fans, since Pride and Prejudice and Zombies remains eighty-percent Pride and Prejudice, and these readers won’t enjoy slogging through Austen’s more drawing-room-paced prose to get to the few nuggets of zombie mayhem—which are styled for the drawing room as well.

And for some reason, I kept imagining Keira Knightley getting into a sword duel with Dame Judy Dench. Oddest thing.

Hey Ryan,

Splendid review. I keep hearing about this book… and the more I hear the better it sounds.

I’m sure it will trigger an inevitable round of quick imitations. GONE WITH THE WIND with zombies. MOBY DICK with ghost pirates. DRACULA with vampires. Or more vampires – you know what I mean.

Can’t wait.

– John

My first thought, John, was David Copperfield… with Orcs!

Glad you liked the review. The book certainly is interesting, there’s no denying that. I will be curious to hear opinions from both the genre side and the Austen side of the fence as the book spreads out more.

When I first heard of this, I thought it was a weird, possibly clever re-imagining. When I later found out it was simply the word-for-word text of Pride and Prejudice with a miniscule amount of the author’s own writing simply tacked on, I decided this was a hack job. You might as well publish the margin notes some thoughtless reader scrawled into a library book. No thanks. That this is in the top sales rank on Amazon is an insult to every real writer out there. This guy should go back to studying porno. No thanks.