My Fantasia Festival, Day 8: Faults, and Predestination adapts Heinlein’s “All You Zombies …”

On Thursday, July 24, I saw two movies. One hinted at the supernatural. The other was a surprisingly faithful adaptation of a classic sf story. On the surface, these films didn’t seem to have a lot in common. But to me they raised similar questions about free will, about how people change, and about whether one can really choose that change.

On Thursday, July 24, I saw two movies. One hinted at the supernatural. The other was a surprisingly faithful adaptation of a classic sf story. On the surface, these films didn’t seem to have a lot in common. But to me they raised similar questions about free will, about how people change, and about whether one can really choose that change.

The first was Faults, which screened at 7:15 at the De Sève Theatre. Directed and written by Riley Stearns, it starred Leland Orser as a man who specialised in deprogramming brainwashed cult members; he was trying to undo the damage a mysterious group called Faults had done to a young woman (played by Mary Elizabeth Winstead, who also produced the film). The second movie I saw right afterward at the Hall Theater at 9:45. It was titled Predestination and adapted Robert Heinlein’s “All You Zombies …” — the title, apparently, was changed to avoid confusion in the marketplace: the filmmakers didn’t want people thinking it had to do with the walking dead. It starred Ethan Hawke and Sarah Snook in her first star role in a feature film. Much of the movie was taken directly from the story, the main changes being additions which helped the story work on screen — and which also ultimately challenged the original story, adding a new ending beyond Heinlein’s text.

I’ll start with Faults, which is in many ways an excellent film that does an awful lot right. It’s a period piece set (so far as I could tell) somewhere around 1980. I mention this because this decision affects both atmosphere and plot: there are no cell phones, no Internet. I’ve noticed a number of films at Fantasia set in the 70s or 80s and you can see the logic. The plot becomes simpler to manage. And you can evoke a time with props and costumes that are probably relatively cheap and easy to find. In this case I think it also taps into a fear of cults and brainwashing that was in the air in the post-Jonestown years.

The film begins as a bleak, straight-faced comedy, with cult deprogrammer Ansel Roth trying to get out of paying for a meal in the hotel where he’s been hired to give a lecture. We soon see Roth’s not engaged with his subject; one of his deprogramming jobs went wrong a little while ago, and the girl he was trying to help committed suicide. We learn this when he’s physically assaulted by one of her family members while the audience for his lecture looks on. But after the lecture he’s approached by an older man and woman who want to hire him to deprogram their daughter, Claire. Roth resists at first, but he’s in debt to his agent, who’s hired a thug to collect. So Roth agrees, arranges to kidnap Claire, and imprisons her in a motel room close by her parents. Much of the rest of the movie takes place in that motel suite, as things become increasingly serious. Pressure increases: Roth has to make payments on his debt, which means dealing with Claire’s increasingly controlling father (Chris Ellis). And Claire herself seems to demonstrate peculiar abilities, even as uncanny reminders of Roth’s earlier failure haunt him.

The film begins as a bleak, straight-faced comedy, with cult deprogrammer Ansel Roth trying to get out of paying for a meal in the hotel where he’s been hired to give a lecture. We soon see Roth’s not engaged with his subject; one of his deprogramming jobs went wrong a little while ago, and the girl he was trying to help committed suicide. We learn this when he’s physically assaulted by one of her family members while the audience for his lecture looks on. But after the lecture he’s approached by an older man and woman who want to hire him to deprogram their daughter, Claire. Roth resists at first, but he’s in debt to his agent, who’s hired a thug to collect. So Roth agrees, arranges to kidnap Claire, and imprisons her in a motel room close by her parents. Much of the rest of the movie takes place in that motel suite, as things become increasingly serious. Pressure increases: Roth has to make payments on his debt, which means dealing with Claire’s increasingly controlling father (Chris Ellis). And Claire herself seems to demonstrate peculiar abilities, even as uncanny reminders of Roth’s earlier failure haunt him.

The movie grows more serious at it goes along without ever losing its wit or intelligence. The tone’s handled masterfully. The film’s largely built on static shots, using slow zooms and edits to create a visual rhythm. That helps the deadpan, uncomfortable humour early on; it helps the equally-uncomfortable dramatic tension later. And it helps point up the excellent work of the actors, particularly when Orser and Winstead share the screen. They throw tightly-written dialogue at each other as though this were a more humanistic Mamet piece, and you feel the excitement of watching two strong performers aggressively working language while reacting to each other’s work at the same time.

The movie grows more serious at it goes along without ever losing its wit or intelligence. The tone’s handled masterfully. The film’s largely built on static shots, using slow zooms and edits to create a visual rhythm. That helps the deadpan, uncomfortable humour early on; it helps the equally-uncomfortable dramatic tension later. And it helps point up the excellent work of the actors, particularly when Orser and Winstead share the screen. They throw tightly-written dialogue at each other as though this were a more humanistic Mamet piece, and you feel the excitement of watching two strong performers aggressively working language while reacting to each other’s work at the same time.

The character choices in the film are generally subtle and effective. Roth is a powerful creation, in quiet despair at the beginning of the film, forced almost against his will to return to the job he thought he knew, then struggling to keep things together as the pressure mounts. Winstead’s Claire is just about as fascinating through much of the film. Has she been manipulated by the cult, or given new self-confidence? If she’s chosen to be a part of Faults, is that a freely willed choice? If she has to be deprogrammed to leave Faults, in what sense is that freely willed? If someone chooses “free will” for another person, is that a real choice? What does free will actually mean?

We don’t get much of a sense of what Faults is like as a group. We learn that members are striving to gain psychic levels, that their mysterious leader is named Ira, presumably to indicate wrath (which makes sense by the end of the film), and, perhaps most thematically important, that their name comes from “faults” in the tectonic sense. A fault is a site of potential damage, also a place of possibility for change — “from the fault comes a change,” says the film — and a place where pressures from different sides come together. So all through the movie we see different people pushing each other, trying to exploit and manipulate one another, and we wonder which fault in which person will give way first and in which way.

That all comes to a head in the film’s final twist. There’s no need to describe it here; enough to say to that I’m not sure it works. It’s not that it’s not set up well — I was actually fairly sure it was coming well before it was unveiled. But part of the reason I saw it coming was that I’d seen something very like it before in a B-horror movie (if you want to know, this movie). I found myself removed from the drama of the film as I watched it unfold, since it tends to undo much of the movie’s apparent tension and explain events with an improbably complex scheme. You don’t know why the target is chosen as the target, or why the scheme unfolded in the way it did rather than some more direct operation.

That all comes to a head in the film’s final twist. There’s no need to describe it here; enough to say to that I’m not sure it works. It’s not that it’s not set up well — I was actually fairly sure it was coming well before it was unveiled. But part of the reason I saw it coming was that I’d seen something very like it before in a B-horror movie (if you want to know, this movie). I found myself removed from the drama of the film as I watched it unfold, since it tends to undo much of the movie’s apparent tension and explain events with an improbably complex scheme. You don’t know why the target is chosen as the target, or why the scheme unfolded in the way it did rather than some more direct operation.

That being said, the twist is executed about as well as it’s possible to do it. It unfolds logically, and is internally coherent. The only question is whether it undermines some of the impact of what went before it, and I’m frankly ambivalent about that. I want to like the movie, which does everything else so well. But the twist tends to lessen much of the sense of different pressures at work on the characters. Faults is a strong movie, but I’m not sure it ends up as strong as it might be. Still, it’s well-written, with a strong sense of character, excellent direction, and powerful acting.

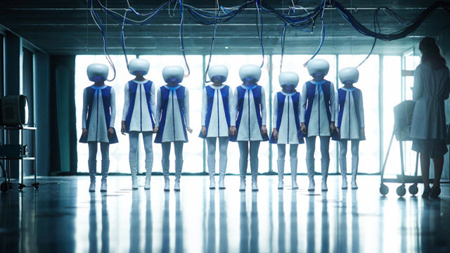

Across the street at the Hall Theater, Predestination was preceded by the world premiere of a short film called In the Pale Moonlight, directed by Australian Tin Pang. It’s a science-fiction story, set in the near future after an outbreak of a plague. Revolving around a scene at a clinic that happens to have some vials of a cure, it’s a tense thriller with some well-executed violence. I thought it tried to develop character, but the payoff felt routine. By contrast, the atmosphere came across well, and the worldbuilding was exceptional. This future had a distinctly 1940s air, with newsreel-like broadcasts on holo-screens and period music. Overall, the story was competent, but the direction and vision were actively interesting.

Before going on to talk about Predestination, I should say in the interests of full disclosure that I’ve never been a Heinlein fan, and I never cared much for “All You Zombies.” There’s a point in that story where one character sets a younger character up to go do a certain thing while knowing that fate has already decreed that the younger man will do another; I could never understand why that character did the thing he did rather than the thing he wanted to — what was his motivation, beyond the needs of the plot? (Of course, even to say this is to skip over the question of what makes a character a separate character, but so it goes.) I felt the movie version went a long way to answering that question in a credible fashion, even finding the answer in a creative reading of certain lines of the original text. And in general I felt co-directors and co-writers Peter and Michael Spierig did an excellent job of adapting the story, cleverly bringing out themes and ironies. All in all, I found I preferred the movie to the source text.

Before going on to talk about Predestination, I should say in the interests of full disclosure that I’ve never been a Heinlein fan, and I never cared much for “All You Zombies.” There’s a point in that story where one character sets a younger character up to go do a certain thing while knowing that fate has already decreed that the younger man will do another; I could never understand why that character did the thing he did rather than the thing he wanted to — what was his motivation, beyond the needs of the plot? (Of course, even to say this is to skip over the question of what makes a character a separate character, but so it goes.) I felt the movie version went a long way to answering that question in a credible fashion, even finding the answer in a creative reading of certain lines of the original text. And in general I felt co-directors and co-writers Peter and Michael Spierig did an excellent job of adapting the story, cleverly bringing out themes and ironies. All in all, I found I preferred the movie to the source text.

But I would think that if you are a fan of Robert Heinlein, you’ll still want to see this movie. You may not agree with certain things it does. But I think you’ll want to see it, if only to disagree with it. The core of the movie is a straight adaptation of “All You Zombies …” that includes virtually everything in the original story, including a good chunk of the text. Some things are expanded, and a subplot adds another level of twist to the near-paradoxes of the original. That subplot helps the story play cinematically (it gives a reason why the two main ‘characters’ don’t look alike, for example) but also challenges the Heinlein tale: it goes past the end-point of the source text, suggesting a conclusion that seemed to me to fit nicely with what had gone before while turning the whole saga into a perfect möbius strip. The Heinleinian competent man faces another turn of fortune’s wheel, and ends his own story.

The movie starts at a distance from the original text: there’s a bomb that goes off, then a member of a futuristic temporal police force is given an undisclosed mission, and then we get to the real start of the story. It’s 1970, and a man walks into a bar. He chats with the bartender, and promises to tell one hell of story. And does. The film moves back and forth easily between flashbacks narrated by the storyteller and scenes in the bar where the storyteller and bartender chat and overhear news broadcasts about a mad bomber. The end of the story is not the end, but the beginning, and before long we find out what was really happening during the course of the teller’s tale.

The movie starts at a distance from the original text: there’s a bomb that goes off, then a member of a futuristic temporal police force is given an undisclosed mission, and then we get to the real start of the story. It’s 1970, and a man walks into a bar. He chats with the bartender, and promises to tell one hell of story. And does. The film moves back and forth easily between flashbacks narrated by the storyteller and scenes in the bar where the storyteller and bartender chat and overhear news broadcasts about a mad bomber. The end of the story is not the end, but the beginning, and before long we find out what was really happening during the course of the teller’s tale.

Among the clever things the adaptation does is take a story written in the late 1950s but set in the 60s and 70s, and keep it set firmly in the 1960s and 1970s as we knew them. It so happens that this version of those years happen to have space flight and time travel. But socially they seem to be the times we knew, so this choice helps bring out the original story’s take on gender and gender roles. If the story projected 1950s values forward, the film works with that from the perspective of 2014. It’s a decision that builds itself into a major motif in the film, visible even in the set dressing (the restroom signs over the bartender’s shoulder are flaring signs reading “gentlemen” and “ladies,” visible at significant moments).

And, of course, the film develops the theme of predestination. This is another place where the film departs slightly from the story, I think for the better (though fans of the original might well disagree). The characters, especially Hawke’s, are more conflicted about the things they do while acknowledging their necessity. The plot doesn’t change, everybody ultimately does essentially the same things they do in the original, but you see them hesitate over it in a way that feels more credible. I’m specifically thinking of a scene Ethan Hawke has in a nursery, in which he steals a baby; it’s dramatically almost necessary that he hesitates at this point, though this does change the character as depicted in Heinlein’s story. Here the characters are less content with fate. But it’s even clearer that they have no choice.

And, of course, the film develops the theme of predestination. This is another place where the film departs slightly from the story, I think for the better (though fans of the original might well disagree). The characters, especially Hawke’s, are more conflicted about the things they do while acknowledging their necessity. The plot doesn’t change, everybody ultimately does essentially the same things they do in the original, but you see them hesitate over it in a way that feels more credible. I’m specifically thinking of a scene Ethan Hawke has in a nursery, in which he steals a baby; it’s dramatically almost necessary that he hesitates at this point, though this does change the character as depicted in Heinlein’s story. Here the characters are less content with fate. But it’s even clearer that they have no choice.

The movie’s sleekly-shot — especially in the brightly-coloured scenes in the early 60s — and well-acted. Hawke’s strong as the bartender, while Sarah Snook anchors the story. She plays male and female and an unexpected transition between the two, and finds an emotional coherency that makes it all work. That, along with writing sensitive to the original and alive to subtext, made for a film that was a pleasant surprise even though I knew the story it told.

This was the Canadian premiere of Predestination, and I was wondering whether the audience in the packed Hall Theatre would follow the twists and turns and general oddness of Heinlein’s original tale. On the whole, it seemed they did. There was laughter, but it seemed to be mostly laughs of recognition when various plot points came clear. Afterward, I asked the people sitting beside me what they thought; they said they’d liked it, and were surprised to hear that much of it came from a story written in 1958 (they’d thought it was swiped from a Red Dwarf episode). That’s one of the hallmarks of a good adaptation, I think, when it brings out strengths in its original text, and especially shows how radical and transgressive that text still is. I thought Predestination was a very successful film, and I’m genuinely curious how it’ll do in general release.

This was the Canadian premiere of Predestination, and I was wondering whether the audience in the packed Hall Theatre would follow the twists and turns and general oddness of Heinlein’s original tale. On the whole, it seemed they did. There was laughter, but it seemed to be mostly laughs of recognition when various plot points came clear. Afterward, I asked the people sitting beside me what they thought; they said they’d liked it, and were surprised to hear that much of it came from a story written in 1958 (they’d thought it was swiped from a Red Dwarf episode). That’s one of the hallmarks of a good adaptation, I think, when it brings out strengths in its original text, and especially shows how radical and transgressive that text still is. I thought Predestination was a very successful film, and I’m genuinely curious how it’ll do in general release.

(You can find links to all my Fantasia diaries here.)

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

[…] The Fatal Encounter, and The Huntresses. Here I take a close look at The Guardians of the Galaxy. Here‘s a look at Faults, and an adaptation of Robert Heinlein’s “All You Zombies […]