Romanticism and Fantasy: The French Experience

In my previous posts about Romanticism and fantasy, I looked at British literature in the 18th century through to 1789, and tried to track the emergence of a certain kind of fantastic fiction. In order to understand what happens in British writing (and politics) after 1789, though, we have to look at what happens in France.

In my previous posts about Romanticism and fantasy, I looked at British literature in the 18th century through to 1789, and tried to track the emergence of a certain kind of fantastic fiction. In order to understand what happens in British writing (and politics) after 1789, though, we have to look at what happens in France.

Before continuing, I need to emphasise: I am not an academic, or a professional historian. I’ve read a fair amount about the period, and I have an intense fascination with Romantic literature in English. These posts come out of that fascination, and are an attempt to relate what I see in that literature with the contemporary fantasy fiction that seems to me to be its direct descendant. All of which is to say that in writing about French literature and history, I am even more of a dilettante than in discussing British writing. There are people who dedicate their lives and careers to making sense of these subjects, and dissecting their various meanings; I am not one of them.

Having said that, it seems to me that the element of fantasy I found in English literature in the late eighteenth century was not present in contemporary French writing in the same way, or to the same degree. In Britain, it seems almost as though the suppression of the fantastic by neo-classical norms led to its eruption later in the century, at first under cover of antiquarianism, then more and more openly. In France, even more classical in its orientation than Britain, that process didn’t happen; instead it seems another type of fantastic fiction came to prominence.

I.

I.

This is not the place for a full history of this period of French literature, but it is worth pointing out that the 17th century saw the French language regulated and, so it has been said, ‘purified.’ This process of linguistic development was guided and encouraged by the Académie Française, an association of intellectuals founded by Cardinal Richelieu in 1634. The Académie was to establish the laws of the French language, and determine as well the laws for French literature. Later Académies for other arts followed, part of a centralising trend; the 17th century was an age of increasing absolutism under Louis XIV. The actual members of the Académie were not necessarily the greatest writers of the time — and no women were elected to the Académie, until, as it turned out, 1980 — but the Académie did produce a grammar and dictionary, both fairly late in the century. The Académie also attempted to codify laws for rhetoric, and establish rules for the proper practice of poetry. (No equivalent to the Académie ever existed in Britain, though some English writers in the 18th century did speak wistfully of the idea of an English Academy.)

That being noted, you can find some interesting examples of the fantastic, or things that partake of the fantastic, in 17th century French literature. For example, in 1657 a work called L’autre monde (The Other World) was published, a somewhat bowdlerised version of the original text, Histoire comique des états et empires de la lune (Comic History of the States and Empires of the Moon). It was a posthumous work by a man named Cyrano de Bergerac. Bergerac had been part of a philosophical and literary movement called libertinism, which was skeptical, satirical, and often anti-religious in outlook. L’autre monde was proto-science fiction, in which a trip to the moon reveals a society both like and pointedly unlike the earth. It’s an early example of the satirical and fantastical traveller’s tale.

Conversely, in 1654 Madeleine de Scudéry published Clélie, histoire romaine (Clelia, a Roman Story), which contained “La carte de Tendre,” an allegorical map of the fictional country of Tenderness. This was an imagined world, inset in a realistic story that itself opened new ground in the developing novel form by emphasising conversation and interiority of character over external action. It was imitated and parodied many times.

Clélie came out of what has come to be called salons: regular meetings of wits and writers, many of them female, typically presided over by an aristocratic woman. Salons were a kind of private academy, creating spaces for discussion, spaces in which official censors had little influence. Witty verse and deftly-written letters were particularly celebrated, but the salons also helped to unify the developing French language, encouraging linguistic invention as well as brilliant conversation. They were also often political. Salon women tried to enunciate and claim rights such as the right to decide when and whether they would bear children. Clélie’s discussion of love and tenderness was related to these kinds of feminist concerns. As well, discussions in the salons helped inspire the civil war called the Fronde (1648-1653). Nevertheless, the years after the Fronde would not only see the influence of the salons at its height, but also a dismissal of salon art as “préciosité” — self-conscious preciousness and frivolity.

Clélie came out of what has come to be called salons: regular meetings of wits and writers, many of them female, typically presided over by an aristocratic woman. Salons were a kind of private academy, creating spaces for discussion, spaces in which official censors had little influence. Witty verse and deftly-written letters were particularly celebrated, but the salons also helped to unify the developing French language, encouraging linguistic invention as well as brilliant conversation. They were also often political. Salon women tried to enunciate and claim rights such as the right to decide when and whether they would bear children. Clélie’s discussion of love and tenderness was related to these kinds of feminist concerns. As well, discussions in the salons helped inspire the civil war called the Fronde (1648-1653). Nevertheless, the years after the Fronde would not only see the influence of the salons at its height, but also a dismissal of salon art as “préciosité” — self-conscious preciousness and frivolity.

The literary trend from 1660 on was toward neo-classicism, and the establishment of rules for approved art. In that year the great playwright Pierre Corneille published a collection of his plays which included three essays on the theatre; these essays laid down rules extracted from (or distantly inspired by) Aristotle. Plays shouldn’t cover a time of more than twenty-four hours, should take place in one setting only, should never have the stage empty of characters, and so forth. Corneille, a good classicist, believed that the ancients had determined the laws of good art, and moderns could only try hopelessly to live up to their example. The restraint and simplicity implied by classicism was at odds with the preciosity of the salons.

In the early 1670s Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux took his four-canto poem L’art poétique (The Art of Poetry) to the salons. In 1664 he’d written (though not published) a satire of stories such as Clélie, the Dialogue sur les héros de roman (Dialogue on the Heroes of Romance). His new poem was a long argument in favour of neoclassical ideals. Boileau held up the ancients as the only writers worth following, and mocked moderns. The work gained him the title of “Lawmaker of Parnassus” — the muses, the dwellers of Parnassus, were subject to the precepts of Boileau’s criticism. In 1684, Boileau was elected to the Académie Française; neoclassicism seemed the dominant critical ideology.

In the early 1670s Nicolas Boileau-Despréaux took his four-canto poem L’art poétique (The Art of Poetry) to the salons. In 1664 he’d written (though not published) a satire of stories such as Clélie, the Dialogue sur les héros de roman (Dialogue on the Heroes of Romance). His new poem was a long argument in favour of neoclassical ideals. Boileau held up the ancients as the only writers worth following, and mocked moderns. The work gained him the title of “Lawmaker of Parnassus” — the muses, the dwellers of Parnassus, were subject to the precepts of Boileau’s criticism. In 1684, Boileau was elected to the Académie Française; neoclassicism seemed the dominant critical ideology.

As it happened, by that time the salons had taken up a very unclassical form as a vehicle for their wit: the fairy tale. The telling of tales, elaborated with the clever use of language and metaphor, seems to have begun as early as 1670. In 1690 a collection was published by Marie-Catherine Le Jumel de Barneville, baronne d’Aulnoy. More would follow.

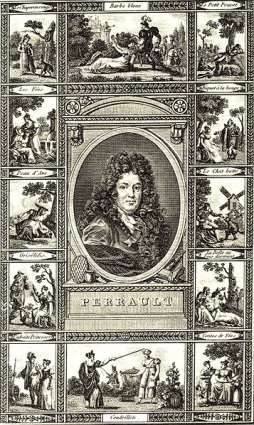

One of the salon writers was Charles Perrault, an enemy of Nicolas Boileau — as a child, Boileau had been a patient of Perrault’s brother, a physician and architect, and as an adult was displeased with the care he’d been given; in 1671 Boileau mocked Perrault in L’art poetique, and Perrault managed to have its publication blocked for a time. The two men were naturally on different sides in a literary war, the Quarrel of the Ancients and the Moderns, Boileau holding that classical writers were models for the moderns, Perrault arguing that contemporary writers were as good as any classics. It has been suggested that Perrault’s 1697 fairy tale collection Histoires ou Contes de temps passé, avec des Moralitez (Histories, or Tales of Past Times) was influenced by the debate. Whether this is so or not, it is worth noting that the frontispiece to the book showed an old woman reading the stories to children, with a sign on the wall reading “Contes de ma mère l’Oye,” or “Mother Goose’s Tales” — a traditional term in France that through Perrault entered the English vocabulary.

In a sense, though, it seems that the publication of these collections of Perrault’s writings marked the end of the first great wave of literary fairy tales. A second soon arrived. From 1704 to 1717 Antoine Galland published his translation of The Thousand and One Nights. Imitations and parodies followed. The book established a fashion for Arabic or ‘Oriental’ fictions set in all manner of remote lands, often meant to make a direct allegorical or philosophical point. These mixed with literary fairy tales and travellers’ tales (perhaps especially after the baron de Montesquieu published his Lettres persanes, which satirised French society by presenting letters written by a fictional sultan supposedly travelling through France), and some of them reached novel length, though so far as I can tell without any of the novel’s characteristic inwardness or sense of character. The decades after 1730 seem to have seen a particular surge in popularity of fairy tales, and 1731 saw the first publication of Le cabinet des fées, a three-volume anthology of the better tales.

In a sense, though, it seems that the publication of these collections of Perrault’s writings marked the end of the first great wave of literary fairy tales. A second soon arrived. From 1704 to 1717 Antoine Galland published his translation of The Thousand and One Nights. Imitations and parodies followed. The book established a fashion for Arabic or ‘Oriental’ fictions set in all manner of remote lands, often meant to make a direct allegorical or philosophical point. These mixed with literary fairy tales and travellers’ tales (perhaps especially after the baron de Montesquieu published his Lettres persanes, which satirised French society by presenting letters written by a fictional sultan supposedly travelling through France), and some of them reached novel length, though so far as I can tell without any of the novel’s characteristic inwardness or sense of character. The decades after 1730 seem to have seen a particular surge in popularity of fairy tales, and 1731 saw the first publication of Le cabinet des fées, a three-volume anthology of the better tales.

But another movement was underfoot in France in the 1730s. In 1734 François-Marie Arouet, writing under the pen name Voltaire, published his Lettres philosophiques. The letters were the fruit of a forced trip to England — Voltaire had gotten into a quarrel with a nobleman, intended to challenge the man to a duel, was put into the Bastille, and allowed out only if he agreed to an exile in London — and fitted into an emerging discourse of philosophical works which favoured reason over revelation, tradition, or authority. Voltaire and his fellow philosophes argued passionately for rationalism, for progress and freedom of thought. Perhaps the greatest product of this Enlightenment was the Encyclopédie, published from 1751 to 1772, edited by Denis Diderot and Jean Le Rond d’Alembert, which set forth a theory of knowledge and presented a rationalist critique of virtually everything, using irony and cunning cross-references to draw connections censors would not allow to be made explicit.

It is notable that the greatest of the Enlightenment philosophes did not hesitate to take up the form of the romantic tale. Voltaire’s 1747 Zadig, for example, used the story of a Babylonian philosopher — complete with basilisks and angels — to present a social satire. Diderot produced Les bijoux indiscrets in 1748, allegedy in order to prove to his mistress he could turn out a licentious novel in two weeks (the word ‘pornography’ had not yet been invented). ‘Bijoux,’ literally ‘jewels,’ was slang for the female genitals, and the story concerned a sultan who acquired a magic ring that gave voices to the privates of his harem-women. Diderot’s story was in fact one of a number of erotic or at least highly sexualised fairy tales that came along in the 1730s and 40s.

In 1758, Diderot’s friend and protegé, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, published a fairy tale, La reine fantastique. It’s a minor satirical work, but it’s a sign of how widespread the fairy tale form had become. Rousseau was a gifted, troubled man, who broke from Diderot at about the same time as he published his fairy tale. Intellectually, the two men had their differences; Rousseau can be viewed as the last of the Enlightenment philosophes, the first of the Romantics, or both. In his time, he was most celebrated for his 1761 novel Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse. It was a sensation throughout Europe; though it was an intensely realistic novel, influenced by Richardson, it became identified with Romanticism due to the vivid realisation of that realism and its theme of sexual passion. Rousseau rejected any trace of preciosity, writing as directly and emotionally as it could. His philosophical writing was also important. Notably, in 1755 he published a Discours sur l’origine et les fondements de l’inégalité parmi les hommes (Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men), and in 1762 published an important essay, Du contrat social. He died in 1778; a posthumous autobiography, the Confessions, further established his credentials as an apostle of a new kind of selfhood that came to be associated with Romanticism.

In 1758, Diderot’s friend and protegé, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, published a fairy tale, La reine fantastique. It’s a minor satirical work, but it’s a sign of how widespread the fairy tale form had become. Rousseau was a gifted, troubled man, who broke from Diderot at about the same time as he published his fairy tale. Intellectually, the two men had their differences; Rousseau can be viewed as the last of the Enlightenment philosophes, the first of the Romantics, or both. In his time, he was most celebrated for his 1761 novel Julie, ou la nouvelle Héloïse. It was a sensation throughout Europe; though it was an intensely realistic novel, influenced by Richardson, it became identified with Romanticism due to the vivid realisation of that realism and its theme of sexual passion. Rousseau rejected any trace of preciosity, writing as directly and emotionally as it could. His philosophical writing was also important. Notably, in 1755 he published a Discours sur l’origine et les fondements de l’inégalité parmi les hommes (Discourse on the Origin and Foundations of Inequality among Men), and in 1762 published an important essay, Du contrat social. He died in 1778; a posthumous autobiography, the Confessions, further established his credentials as an apostle of a new kind of selfhood that came to be associated with Romanticism.

But let’s skip back a few years. Voltaire’s Lettres philosophiques didn’t just help to usher in the Enlightenment, they also helped foster an emerging interest in English literature in France. There seems to have been a fad for English writing from the 1750s to 1770s, and for German writing from the 1760s. Shakespeare was translated twice, partially in 1746 and then completely from 1776 to 1783; Voltaire was irritated, notably referring to Shakespeare as a “drunken savage,” while on the other hand Diderot wrote of Shakespeare as “a terrible mortal … a colossus who was gothic, but between whose legs we would all pass without our heads even touching his testicles.” Both terms played into an emerging discourse about European literature: Britain as a gothic, Germanic land, opposed to the southern, Latinate, classical culture.

There was one major difference between the publishing industries of the two countries, at any rate. France did not have the relative liberty of the press that England did. Government officials oversaw all printed material — in theory. In practice this was an impossibility, given the amount of material involved. Rather than suppress radical or obscene material, the government censors soon evolved a system of complex, unofficial categories for the literature they supposedly controlled, and a grey market for censored books developed; indeed, exploded. Radical philosophy, political scandal, and (illustrated) pornography were all distributed by these clandestine channels, and seem to have constituted a majority of the reading material of France at the time. Many of the great books by writers like Voltaire and Diderot were officially illegal, or circulated in manuscript before being committed to print.

1771 saw the publication, through these illegal channels, of a social satire that also happens to be a work of science fiction. L’An deux mille quatre cent quarante, rêve s’il en fût jamais (The Year 2440: A Dream if Ever There Was One) was probably written by Louis-Sébastien Mercier, a hack writer. It’s a utopian tale about a man who falls asleep and wakes up seven hundred years in the future. Though social systems and fashions are changed, Mercier can’t imagine technological progress; people still drive horse-drawn carriages. Mercier’s friend and fellow “Rosseau de ruisseau” (Rousseau of the gutter) Nicolas-Edmé Restif de la Bretonne, was a much more prolific creator of utopias. In six volumes, five of them published between 1770 and 1789, with the last coming in 1797, he projected schemes to reform or uplift men, women, language, and various other elements of society (the title of the 1770 volume on prostitutes introduced a new word: Le pornographe).

1771 saw the publication, through these illegal channels, of a social satire that also happens to be a work of science fiction. L’An deux mille quatre cent quarante, rêve s’il en fût jamais (The Year 2440: A Dream if Ever There Was One) was probably written by Louis-Sébastien Mercier, a hack writer. It’s a utopian tale about a man who falls asleep and wakes up seven hundred years in the future. Though social systems and fashions are changed, Mercier can’t imagine technological progress; people still drive horse-drawn carriages. Mercier’s friend and fellow “Rosseau de ruisseau” (Rousseau of the gutter) Nicolas-Edmé Restif de la Bretonne, was a much more prolific creator of utopias. In six volumes, five of them published between 1770 and 1789, with the last coming in 1797, he projected schemes to reform or uplift men, women, language, and various other elements of society (the title of the 1770 volume on prostitutes introduced a new word: Le pornographe).

Finally, it’s worth pointing out that the production of fairy tales had continued all this time. Later editions of the Cabinet des fées had republished the best tales throughout the century. The final version, published between 1785 and 1789, ran to forty-one volumes. And at least one of the men who translated tales for this version of the Cabinet, Jacques Cazotte, was also a writer of fairy tales himself. Cazotte’s most successful fairy tales belong to the 1740s, but in 1772 he published a story called Le Diable amoreux (The Devil in Love). It’s different from preceding fairy tales, an occult romance in which a devil falls in love with the magician who called it up from hell. The story was a major influence on later writers, both in France and elsewhere.

Still, it seems to me that the fairy tale is the characteristic form of French fantasy in the century. If neoclassicism and the Enlightenment seemed to suppress the fantastic in England, then in France the Enlightenment found a way to allow the marvellous some reign. As far as I can see, these works have a different feel than the fantasies that would emerge from Romanticism. They seem to be flatter, with little sense of individual psychology or of a consistent fantastic world. They were frequently written as satires or comments on contemporary France, which has the effect of undermining the imaginative integrity of the fantasy. It’s distinctive, but seems to have little direct relevance on the Romantic fictions I’m interested in; Rousseau’s sentimental realism may have had the most impact on English literature of any French work of the period.

Until 1789, when a series of events began that would influence England, and Europe, and the world, quite dramatically.

II.

II.

There has been much argument about the causes and significance of the French Revolution. Whether it was inspired by Enlightenment philsophy or not; whether it represented a revolt of the bourgeois class or not; whether the Terror of 1793-4 was inevitable in 1789. I do not pretend to have a meaningful opinion on these issues. I want here simply to try to set down a timeline of events for the decades following the Revolution, because what is undeniable is that the Revolution had a tremendous impact on the development of Romanticism in England as well as France.

In 1789 an ongoing economic crisis led to disorder in the French countryside and the summoning of the Estates-General, a kind of irregularly-held parliament. The Estates-General convened on May 5, and was inmmediately paralysed by procedural disagreement. There were three equal Estates, one for aristocrats, one for the Church, and one for the 96 percent of the rest of the people. Middle-class lobbying had led to double representation for the Third Estate, which in 1789 therefore had as many representatives as the other two Estates together. Were the Estates to decide on their policy stances each among themselves, and then vote on issues as an Estate (in which case the Third Estate was outnumbered two to one), or should the Estates-General as a whole debate policy and give each representative a vote? The Third Estate insisted on the second procedure; the First and Second disagreed.

After a six-week standoff, on June 17 the Third Estate declared itself the National Assembly of France, and effectively assumed legislative power. King Louis XVI tried to prevent them from assembling in their usual meeting-hall; the members therefore convened in a nearby tennis-court, and swore to provide a constitution for France. Louis was unable to convince the assembly to dissolve; political miscues and a concentration of soldiers in the Paris suburbs led to violence in the streets, and then on July 14 to the storming of the massive jail called the Bastille, a hated symbol of despotism.

Uprisings followed throughout France. On August 4 the National Assembly abolished the feudal system, the traditional ordering of French society dating back about a thousand years, and on August 26 proclaimed a Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. Aristocracy was effectively abolished; ‘citoyen’ replaced ‘monsieur’. Political clubs were formed, notably one that met at an old monastery of the Jacobins. The property of the Church was seized by the state, then the Church itself was made into a state Church. In June of 1791 Louis was deprived of all political power; on Spetember 3 a new constitution was proclaimed, establishing a constitutional monarchy governed by a Legislative Assembly. It didn’t work out, and in 1792 the government was paralysed by a constitutional crisis. Meanwhile, the crowned heads of nations neighbouring France were worried and (especially in the cases of those related to Louis) outraged by the Revolution; the revolutionaries, on the other hand, were eager to export the Revolution to other European monarchies. France declared a pre-emptive war on Austria and Prussia in the spring of 1792.

Uprisings followed throughout France. On August 4 the National Assembly abolished the feudal system, the traditional ordering of French society dating back about a thousand years, and on August 26 proclaimed a Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen. Aristocracy was effectively abolished; ‘citoyen’ replaced ‘monsieur’. Political clubs were formed, notably one that met at an old monastery of the Jacobins. The property of the Church was seized by the state, then the Church itself was made into a state Church. In June of 1791 Louis was deprived of all political power; on Spetember 3 a new constitution was proclaimed, establishing a constitutional monarchy governed by a Legislative Assembly. It didn’t work out, and in 1792 the government was paralysed by a constitutional crisis. Meanwhile, the crowned heads of nations neighbouring France were worried and (especially in the cases of those related to Louis) outraged by the Revolution; the revolutionaries, on the other hand, were eager to export the Revolution to other European monarchies. France declared a pre-emptive war on Austria and Prussia in the spring of 1792.

An attack on the royal family by a radical mob on August 10 was followed in September by the murder of 1400 prisoners in the Paris jails. The radical Jacobins controlled the city government, and now moved to control the national government, declaring France a republic on September 21 — later named the beginning of Year One of the revolutionary calendar. The government was in the hands of a National Convention, which wielded both legislative and executive power. The war took a turn for the better, as France took over the Austrian Netherlands, but this brought the British and the Dutch into the war against France, who wanted to keep France from controlling the Netherlands. Louis was executed early in 1793, the French were driven out of the Netherlands, and counter-revolutions broke out in France — though the allies failed to take advantage.

To meet the unrest, in April executive power was given to the nine-member Committee of Public Safety, controlled first by Georges-Jacques Danton and then, from late July, Maximilien Robespierre. Political purges followed. Paranoia and the fear of counter-revolutionary traitors to France were exacerbated by the July 13 assassination of populist journalist and former Convention member Jean-Paul Marat in his bath by Charlotte Corday. The Reign of Terror, a dictatorship that effectively suspended all rights of the citizens, took hold under Robespierre. Louis’ Queen, Marie Antoinette, was executed in October; many thousands of others, aristocrats and political enemies of the Jacobins, also died by the guillotine. Revolts in the provinces were harshly put down. (In retrospect, particularly notable was a battle at the city of Toulon, then occupied by counter-revolutionaries and British soldiers; a 24-year-old captain conceived and executed the successful capture of a hill where he then positioned his artillery, thus turning the tide of the battle. In recognition, the Corsican-born Napoleon Bonaparte was promoted to brigadier-general.)

In May of 1794 the Church was abolished, replaced with the Cult of Reason. But the Terror was turning against its masters; first Danton, then Robespierre himself were executed (ironically, following a military triumph that restored the Netherlands to France). The powers of the Committee were gradually diminished. (Bonaparte, who had led French forces to a string of triumphs in Italy, was briefly put under house arrest for being too close to Robespierre. He was soon freed.) Various weak governments ruled until November 1799, or, in the revolutionary calendar, 18 Brumaire.

In May of 1794 the Church was abolished, replaced with the Cult of Reason. But the Terror was turning against its masters; first Danton, then Robespierre himself were executed (ironically, following a military triumph that restored the Netherlands to France). The powers of the Committee were gradually diminished. (Bonaparte, who had led French forces to a string of triumphs in Italy, was briefly put under house arrest for being too close to Robespierre. He was soon freed.) Various weak governments ruled until November 1799, or, in the revolutionary calendar, 18 Brumaire.

By that time Bonaparte had conquered northern Italy, effectively stabilising the French military situation in Europe. After an unsuccessful attempt to conquer Egypt, during which time war broke out again between France and Austria, Bonaparte returned to France, overthrew the government, and then returned to the field in Austria. War would continue between France and various configurations of European powers in alliance against her until 1812. Napoleon, who crowned himself Emperor in 1804, won victory after victory. Britain’s Admiral Nelson defeated him at sea near Cape Trafalgar in 1805, but that same year success in a battle at Austerlitz gave Napoleon the upper hand over Austria, Prussia, and Russia; by 1807 all Napoleon’s enemies except Britain had either been conquered or, as in the case of Russia, had sued for peace. The Napoleonic Empire spread over much of Europe. Britain responded by fostering a guerilla war in Spain, distracting Napoleon as other parts of his empire began to rebel.

Finally, in 1812, Napoleon felt he had no choice but to invade Russia, which itself looked ready to resume its former opposition to France. Napoleon led several hundred thousand men, the largest army ever seen in Europe, across the border at midsummer, having had to wait on the provision of fodder for his cavalry. He successfully captured Moscow, the traditional capital of the Russian people, but the government in Saint Petersburg didn’t attempt to negotiate peace, as Napoleon seems to have expected they would. With no supplies, Napoleon had to retreat as winter set in. The Russian army, which had fallen back before him as he advanced to Moscow, now harried his retreat. Between the Russians and the winter, the death toll was incredible. It has been estimated that one man in twenty survived the retreat.

Amazingly, Napoleon then held out for almost two years against the countries he had defeated to establish his empire, before finally surrendering in April, 1814. Napoleon was sent into exile on the island of Elba, and the grandson of Louis XV of France was installed as King Louis XVIII. Representatives of the various European powers met at a congress in Vienna to settle matters involved in the break-up of the Napoleonic Empire and the aftermath of the French Revolution. It appeared events were returning to normal. Until, in February 1815, Napoleon escaped Elba, and over the course of three weeks marched on Paris and forced Louis XVIII to flee.

Amazingly, Napoleon then held out for almost two years against the countries he had defeated to establish his empire, before finally surrendering in April, 1814. Napoleon was sent into exile on the island of Elba, and the grandson of Louis XV of France was installed as King Louis XVIII. Representatives of the various European powers met at a congress in Vienna to settle matters involved in the break-up of the Napoleonic Empire and the aftermath of the French Revolution. It appeared events were returning to normal. Until, in February 1815, Napoleon escaped Elba, and over the course of three weeks marched on Paris and forced Louis XVIII to flee.

Napoleon gathered a new army as the powers of Europe prepared to go to war against him yet again. He attacked the Prussians on June 16, and then, on June 18, attacked the British near the town of Waterloo. The ‘thin red line’ of British troops, commanded by the Duke of Wellington, did not break under Napoleon’s assault, and when the Prussian cavalry joined the battle late in the day, the Emperor was defeated. The ‘hundred days’ of his return had come to an end. He abdicated, and was sent into exile again, on the island of St. Helena, where he died under slightly murky circumstances in 1821.

After Napoleon’s second defeat, the Congress of Vienna reconvened. The balance of power in Europe was restored; a “German Confederation” was established out of the ruins of the Holy Roman Empire; and Switzerland was guaranteed eternal neutrality. The various national powers were naturally conservative, opposed to nationalism and liberal ideas (such as democracy). The settlement of the Congress was designed to repress the dangerous democratic ideas of the French Revolution. The spirit of reaction set in across Europe, and (very broadly speaking) dominated European politics until at least 1848.

Still, despite the semi-regular Congresses the great powers continued to hold, uprisings and revolutions in the name of nationalist or liberal ideas continued here and there. As for France, it was granted a two-chambered legislature on the British model; Louis XVIII was succeeded by Charles X in 1824; and then in 1830 the July Revolution led to fighting on the barricades, the flight of Charles to England, and the installation of the July Monarchy of Louis Philippe I, who ruled until 1848, when he himself was overthrown.

Still, despite the semi-regular Congresses the great powers continued to hold, uprisings and revolutions in the name of nationalist or liberal ideas continued here and there. As for France, it was granted a two-chambered legislature on the British model; Louis XVIII was succeeded by Charles X in 1824; and then in 1830 the July Revolution led to fighting on the barricades, the flight of Charles to England, and the installation of the July Monarchy of Louis Philippe I, who ruled until 1848, when he himself was overthrown.

This all seems far afield from fantasy fiction. But I feel it’s vital background for understanding what happened in literature from 1789 onward. The Revolution wasn’t just a political event; it came almost as a revelation. Its early days were a time of idealism, when anything seemed possible: “Bliss was it in that dawn to be alive,” William Wordsworth later recalled, “but to be young was very heaven.” Conversely, Britain declaring war against France was a bitter blow for many liberals. As time went on and the Revolution first became more vicious, and then more directly threatening with the rise of Napoleon, early professions of faith in the Revolution became viewed as a sign of political unreliability.

Napoleon himself was alternately a hero and a villain, depending on who you asked and when. One of the great musical products of Romanticism, Beethoven’s Third Symphony, was intended by its composer to be dedicated to Napoleon the radical — but when he was told that Napoleon had declared himself Emperor, Beethoven tore up the title-page he’d had prepared, renamed the symphony the Eroica (“heroic” in Italian), and dedicated it to “the memory of a great man.”

Politics and war determined the background for Romanticism, and Romantic fantasies adhered to nations and heroes. We’ll see this play out in many ways over the course of future posts.

III.

III.

And what was happening in France, during these later years? How had Romanticism begun to manifest itself?

It came later than in Britain, by and large, but you can find some examples in the opening years of the century. Arguably, you can find a notorious case even before that; the brutal pornography of the Marquis de Sade (notably 120 Days of Sodom, 1785, and Justine, 1788, revised 1791) used tropes familiar from the developing genre of Gothic fiction. But unlike the Gothic, Sade avoided the fantastic. Critic Chantal Thomas sums it up: “Sade has no deep affinity with texts dominated by magic, sustained by the supernatural, and permeated by a diffuse terror essentially bound to a certain place and atmosphere. His writing is opposed to the use of this type of fantastic. However extreme the imagination of torture and the sophistication of crime in his own works, he makes no appeal to the supernatural.”

In 1802 François-René de Chateaubriand published a meditation on Christianity, Génie du Christianisme, that dealt with Christianity in what would come to be called a Romantic spirit — dwelling on images of tombs, ruins, and the like, and appreciating the gothic architecture of cathedrals like Notre-Dame de Paris. Anne Louise Germaine de Staël, the last of the great salonnières, is significant in this context for her essays. 1800’s De la littérature considérée dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales (The Influence of Literature Upon Society) argued that different cultures produced different kinds of literatures, meaning that absolute ideas of artistic merit were impossible. She also distinguished between literatures of the north and of the south, an idea further elaborated in her 1810 essay De l’Allemagne (Of Germany), arguing that the classical southern culture was descended from pagan Rome, while the gothic northern culture was shaped by medieval Christianity.

But it was at least another decade until Romanticism could be found in verse or fiction, starting with the verse of Alphonse de Lamartine (Méditations Poétiques, 1820). Fantasy emerged in the fiction of Charles Nodier, starting with Smarra (1821). Jean-Jacques Ampère translated some tales by the German writer E.T.A. Hoffmann in 1829; this seems to have started a kind of craze for the fantastic in France, particularly in the form of the tale that may be a fantasy or may be a hallucination or dream. Writers such as Théophile Gautier, Gérard de Nerval, and Prosper Mérimée all wrote significant works of fantasy; so too did Honoré de Balzac, better known as a realist writer. Perhaps above all was Victor Hugo, certainly Romantic and arguably a fantasist, depending on how one wants to characterise works such as Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame) and religious verse such as Le Fin de Satan (The End of Satan, 1886).

But it was at least another decade until Romanticism could be found in verse or fiction, starting with the verse of Alphonse de Lamartine (Méditations Poétiques, 1820). Fantasy emerged in the fiction of Charles Nodier, starting with Smarra (1821). Jean-Jacques Ampère translated some tales by the German writer E.T.A. Hoffmann in 1829; this seems to have started a kind of craze for the fantastic in France, particularly in the form of the tale that may be a fantasy or may be a hallucination or dream. Writers such as Théophile Gautier, Gérard de Nerval, and Prosper Mérimée all wrote significant works of fantasy; so too did Honoré de Balzac, better known as a realist writer. Perhaps above all was Victor Hugo, certainly Romantic and arguably a fantasist, depending on how one wants to characterise works such as Notre-Dame de Paris (The Hunchback of Notre-Dame) and religious verse such as Le Fin de Satan (The End of Satan, 1886).

Romanticism and the fantastic came late to France, then, but eventually did come in force. More than that; it seems to me that while there was a reaction against Romantic fantasy in England during the Victorian age, when fantastic fiction was often considered to be by definition for children, French fantasy by contrast birthed a tradition. That fantastic tradition of the 1830s then continued through both popular serials like Eugène Sue’s Le juif errant (1845) and more ambitious work like Charles Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal (1857), on to the horrific short stories of Guy de Maupassant and the prose poems of Lautréamont’s Les chants de Maldoror (The Lays of Maldoror, 1874; ‘Lautrémont’ is a pseudonym taken from a novel by Sue).

As we’ll see, the Romantic era in British literature came to a fairly distinct close, as one generation of writers was replaced by another, with a different set of techniques and approaches. Fantasy became, to some extent, marginalised. In French I feel — and I am very much an outside observer, so take this as you will — that Romanticism could be said to evolve rather than end, becoming a component of decadence and surrealism. If the form of the fantastic that interests me is slow in coming to France, the corollary seems to be that it was taken seriously for rather longer.

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. His new ongoing web serial is The Fell Gard Codices. You can find him on facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

The influence of British writing on French culture is a fascinating new piece of the Romanticism puzzle for me. The bits I came out of grad school with were mostly about how the Romantic poets sided with the revolutionaries early, only to be horrified and discredited by the Terror. Thank you for another fascinating post.

Sarah: Thank *you* for the comment! I think the connection between revolution and romanticism is fascinating; so’s the question of whether the French Revolution stands for/is a product of Enlightenment, or of Romanticism. I’m looking forward to getting into it a bit in future posts.

In general, though, one of the things I’m finding rewarding is coming across the connections between various areas of the period. I get the impression that a lot of lit studies, particularly in recent decades, have tended to focus on specific ideas or themes as manifested in various texts. Nothing wrong with that, but it seems a little different approach than trying to understand those texts by taking a holistic view to their times. All of which is to say that I’m hoping to find more unexpected links in future.

What happened, as you point out, is the Revolutionary era, and the Napoleonic wars. Georg Lukács in his study of the historical novel, saw it like this:

In other words this era was a singularity, of sorts, perhaps, which made everything fall into before and after, and everyone in Europe and the U.S. knew it and felt it. This unleashed the Romantic era, of which the historical novel was also an expression.

At least this is how I understand it — which does not, of course, make me right per se. 🙂

Love, C.

C: (Do you prefer C or C-Foxessa?) I actually came across a similar argument when I was putting the post on the German writers together; the scholar (Fabian Lampart) might have had Lukacs’ work in mind. It certainly tracks with John Clute’s argument that this was when fantastika developed because this was when people developed a real sense of historical change.

I do think ‘singularity’ works here because there’s a certain density of interconnection. Different trends and themes were brought together, and … united, somehow … and it seems Romanticism came out of that. It’s a pleasantly futile task, trying to unweave all those connections. But if you’re after something specific (like the development of fantasy), maybe it becomes possible. We’ll see.

I don’t quite know how I got my log in handle — it came about somehow the third time I tried to join this login community.

The C stands for my real name, while the rest is what has become, along with my real name, my x-onlandia handle.

That irrrelevancy out of the way — what matters is what Lukács leaves out of his study, The Historical Novel, that he doesn’t speak to, that includes both Alexander Dumas (who matters in terms of Romanticism and Fantasy as you know so well that there’s no reason for me to go into it — including Steve Brust) — and Poland’s HenryK Sienkiewicz, who won the Nobel Prize for Literature, and who I am certain had enormous influence as well on Tolkien. Why Sienkiewicz was not included — Poland, so often eaten by czarist Russia, Poland soon to be eaten by Stalinst Russia, and all the rest of that tragic, horrible history. Lukács wrote this in Russia, in the winter of 1936 – 1937 ….

Love, C.

[…] in English writing from 1760 to about 1790, then looked at elements of fantasy and Romanticism in France and Germany before returning to England to consider the Gothic. I wrote about the work of William […]