Toy Story 3: Genre fiction writers take heed

Warning: This essay contains some spoilers.

Warning: This essay contains some spoilers.

If fairy-story as a kind is worth reading at all it is worthy to be written for and read by adults.

–J.R.R. Tolkien, Tree and Leaf

I don’t get to the theatre too often these days, and with two young daughters in tow more often than not it’s to see a children’s film. But I’m not lamenting this fact, especially when the movies are of the quality of Toy Story 3.

Hey, I love Robert E. Howard, Bernard Cornwell, and the Viking novels of Poul Anderson as much as the next battle-mad fantasy fan, but I’m man enough to admit liking (most) Pixar films as well. And Toy Story 3 might be the best one I’ve seen. Critical consensus is not necessarily a hallmark of a good film (see Blade Runner, panned on its initial release by most critics, recognized as genius years later), but I think it’s telling that Toy Story 3 currently has a 99% “fresh” rating on Rotten Tomatoes. In this case, the critics are spot-on.

Toy Story 3 is a near-perfect children’s film. Like all children’s films, it possesses straightforward story lines, engaging visuals, and brisk action in order to keep young attention spans focused. (If these qualities sound like less than appealing, well, genre films can’t be all things to all people). So why sing its praises on Black Gate? Toy Story 3 serves as an instructive example of how to tell a great story within the confines of a given genre. Just like you can’t get too bogged down in dialogue or non-linear narrative techniques in a movie for kids, that story you submit to Heroic Fantasy Quarterly better contain some elements of sword play and sweeping action if you want to stand a chance of getting it published. If you disregard your audience you’re destined to fail.

But I would also submit that the best genre fiction stretches the boundaries and defies rigid conventions. Toy Story 3 (and the best of the Pixar films) isn’t afraid to bend the definitions of what defines a children’s film. Yes, it has eye-catching visuals and several edge-of-your seat chase sequences to keep even the most antsy kids glued to their seats. There’s a joke nearly every minute of screen time. But it’s also got despair, and darkness, and pain, and well, stuff that also makes it very much for adults.

Likewise, the best heroic fantasy tales contain transcendant elements that elevate it into good literature. Howard explored civilization vs. barbarism in his tales of swords and sorcery. Clothed in the trappings of epic fantasy, J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings is a story about the corruptive influence of power and the equivocal nature of change. We might pick up these stories because we love swords and monsters and wizards, but they continue to be read by subsequent generations when other stories fall by the wayside because they apply to our own lives and resonate with our spirit.

Toy Story 3 explores themes we don’t normally associate with children’s films, like growing up and moving on, and the importance of duty and responsibility. It’s also about forgiveness—with limits. Toy Story 3 teaches us that people are deserving of second chances, and that mercy and forgiveness are honorable. But it also demonstrates that there are limits to forgiveness, and that justice too has its place in the world.

One of the central characters in Toy Story 3 is (work with me here) a fuzzy pink teddy bear named Lots-o’-Huggin. Lots-o’ at first seems like a helpful mentor. Like a wise old grandfather, he shows Buzz, Woody and the gang the ropes of Sunnyside Day Care, a place where the old toys wind up after Andy boxes them up before heading off to college. But Lots-o’ is really a cold, manipulative, mean SOB. You see, years ago Lots-o’ was abandoned and replaced with another fuzzy teddy bear, and the event left him a shattered, bitter soul.

Lots-o’ has a chance for redemption when Woody saves him from certain destruction in a junkyard incinerator. But with a chance to return the favor he double-crosses our heroes and leaves them to die an apparent fiery death. It’s a stunning moment, and one a lesser film would have handled differently, with Lots-o’ playing the role of forgiven hero. But Toy Story 3 breaks this pattern of predictability (which is, regrettably, another trait common to children’s films). Afterwards, Woody realizes that Lots-o’ is a lost cause. “He’s not worth our time,” Woody says to his friends. Lots-o’ is beyond rehabilitation and must be discarded.

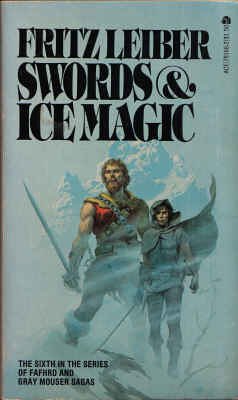

You don’t expect to encounter these types of issues in a children’s genre film. But when you do your hand pauses in the popcorn and you realize you’re watching something great. Kind of like the first time I read Fritz Leiber’s “The Sadness of the Executioner” and, expecting a rollicking sword and sorcery tale, was gobsmacked with a thoughtful meditation on death.

You don’t expect to encounter these types of issues in a children’s genre film. But when you do your hand pauses in the popcorn and you realize you’re watching something great. Kind of like the first time I read Fritz Leiber’s “The Sadness of the Executioner” and, expecting a rollicking sword and sorcery tale, was gobsmacked with a thoughtful meditation on death.

Though Lankhmar and Sunnyside Day Care inhabit two very, very opposite corners of the universe, there’s a lesson here to be learned for all aspiring writer: Don’t settle for the easy and safe sword and sorcery tropes, lest you end up writing the next Thongor novel. We all love our genre stories. We want larger-than-life heroes, and battlefield carnage, and diabolical villains. But the best authors don’t let the conventions handcuff them. The trick is to maintain fidelity while breaking some rules in the name of art.

Just like Toy Story 3.

I love that tolkien quote. It makes me think of old disney movies and buggs bunny. I loved those as a child and i still love them and i’m 21. My uncle and i quote tex avery cartoons all the time. and he’s 40.