Short Fiction Reviews: Virginia Quarterly Review and Subterranean Magazine

A Look at Current Fantasy Magazines

By David Soyka

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

Philip Roth can write an alternate history, Cormac McCarthy an end-of-the-world tale, Margaret Atwood a Frankenstein parable even as she claims she doesn’t write science fiction junk. No one calls Thomas Pynchon a fantasy writer, though whatever the hell he writes surely is fantastical. But they don’t become tarnished as genre writers when they write genre.

Philip Roth can write an alternate history, Cormac McCarthy an end-of-the-world tale, Margaret Atwood a Frankenstein parable even as she claims she doesn’t write science fiction junk. No one calls Thomas Pynchon a fantasy writer, though whatever the hell he writes surely is fantastical. But they don’t become tarnished as genre writers when they write genre.

But, times are changing. In the early 1980s, Doris Lessing caught critical hell when she wrote the science fictional Canopus series; some maintain this caused her to be taken off the short list for the Nobel Prize in Literature. These days, Michael Chabon (whose “Gentlemen of the Road” is currently serialized in the New York Times Magazine) crosses over from mainstream author to genre storyteller without losing credibility or creating much fuss among critics.

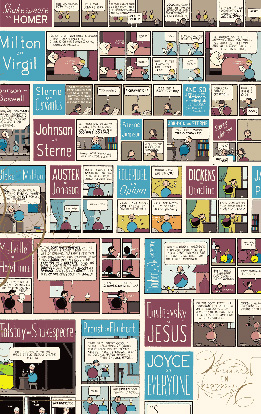

Further evidence of this trend is when literary magazines unabashedly publish genre stories, albeit authors with established literary credentials. Case in point is The Virginia Quarterly Review and its special “Writers on Writers” supplement. The issue features 11 (12 if you count Chris Ware’s cover comic strip) stories that in one way or another reference famous writers. Some of these are genre writers — Philip K. Dick, Edgar Alan Poe — while others situate mainstream authors in genre settings.

The most recognizable author to genre readers is Jonathan Lethem, who seems to have accomplished a reverse-Chabon in moving from genre fiction to the literary mainstream. Interestingly, then, that his subject is Phil Dick, whose claim for literary respectability is a scholarly Library of America collection of four novels, edited by the selfsame Lethem. Of course, Dick was frequently a character in his own stories, as well as in Michael Bishop’s novel Philip K. Dick is Dead, Alas. (See also “Jellyfish,” by Mike Resnick and David Gerrold in the Solaris Book of New Science Fiction, which satirizes not only Dick, but Kurt Vonnegut and a host of famous science fiction writers, including the authors themselves.) As you might expect, in “Phil in the Marketplace,” Lethem places our hero, identified as “the writer of Ubik,” in various situations where he encounters out-of-the-ordinary people in slightly out-of-joint sequences of time and circumstances at odds with normal expectations, all with the intent, as the title implies, of promulgating Dick’s fictional world view. I imagine, however, that readers unfamiliar with Dick won’t have a clue what the point of all this might be.

Notably, though, a number of stories here could be descried as “Dickian” in that they concern some kind of bizarre alternate reality. In Brock Clarke’s “The Pity Palace,” Antonio Vieri’s wife has left him for Mario Puzo. Which is a bit odd considering that Mario has been dead for seven years. Antonio stays in his Florence apartment, reading Puzo novels to figure out why his wife left for the author. His self-imposed exile becomes sufficiently well-known that his apartment becomes a tourist attraction (the titular “pity palace), in which Antonio is visited by all sort of strange characters, including members of the Mario Puzo society. In a riff on Samuel Beckett, it is up to Antonio to decide if he should stay in his apartment, or venture forth in search of his wife and a happy ending, “just like in a book.”

Sort of like Dick in that it takes place in different, albeit actual, timelines, is “Aerial Bombardment.” (It is, however, more traditional realistic fiction, as are two other stories in this collection, Ron Hansen’s depiction of Gerald Manley Hopkins in “Hopkins in Wales,” and Edmund White’s contrast of Henry James and Stephen Crane in “One Endless English Evening.”) Christopher Tilgham writes both about himself and the poet Richard Eberhart in what I assume is a semi-autobiographical account of their shared experiences training naval gunners — and contemplations about what happens warfare skills when put into practice — at Dam Neck, Virginia twenty-five years apart. The casualties of war are also the subject of John McNally’s “The End is Nothing, The Road is All,” in which a former paratrooper in the Normandy invasion, now a homeless junkie, converses with, or imagines he converses with, Nelson Algren, whose literary subjects were the down and out.

“Due West” by James P. Olthmar is a Twilight Zone-type story in which you already know the ending by the opening line, “The car that is about to crush me is driven by Nathanial West.” Making it even more weird is that the narrator is on his way back from a health foods store in December 2005 and West was killed in a car accident 65 years earlier. The fact that we have a collision of timelines, plus a narrator describing his own death by someone from the past, is classical Dick, though I don’t know if that was Olthmar’s intention. Rather, it is a mediation on fortune, and not the fortunate kind. Steve Almond’s alternate reality is to project the future of James Frey, the memoirist who famously confessed that he made up his memories. In “Controversial Author and Cultural Icon Found Dead,” Almond makes up Frey’s future obituary to funny effect.

While most people likely to pick up VQR may not be what is unfortunately termed as “Dickheads,” they probably have, however, some general ideas about Emily Dickinson, even if they aren’t overly familiar with her poetry (as, I confess, I am not). Still, they’ll have no trouble with “EDickinson RepliLuxe,” the most science fictional of all the stories in this slender volume, in which the genre hopping Joyce Carol Oates does a turn at Asimov. A lonely elderly couple acquire an android version of the famous poet. By law, the android is built without sexual apparatus. The husband, however, finds himself strangely attracted to the demure replica and begins to act on that attraction. The wife finds out and decides that women must stick together to protect their sex, even if one of them doesn’t happen to have one.

In “Recluse,” Elizabeth Gaffney imagines how the granddaddy of the horror genre, Edgar Alan Poe, may have described the experience of his own actual demise. “I would rather by far be buried live than fall prey to a death without poetry of any sort.” Gaffney provides, if not poetry, then at least some nice irony. Not nearly as weird as Angela Carter’s classic “The Cabinet of Edgar Allan Poe,” Gaffney does nicely capture how Poe may very well have confronted the horror of it all — with a dose of disbelief.

“Writers on Writers” was a supplemental issue for VQR subscribers; non-subscribers can order a copy on-line at the magazine’s website; there are also a few select stories available to read on-line, but access to all eleven stories through the web site is available to subscribers only.

Beginning with its Winter 2007 issue, Subterranean Magazine is now available for free on its website; Issue 8 will be the last print edition and subsequently will move exclusively on-line, apparently with regular weekly updates of new fiction and columns, as opposed to a single fixed issue publication. Obviously, it’s less expensive to publish on-line than hard copy, though exactly why they are giving away content is unclear. The printed magazine was sold for $6 an issue, with a special “collector’s limited edition” hardcover sold for $80. (Interestingly, if you do a Google search, you can find issue #4 available for free as a PDF file.)

Beginning with its Winter 2007 issue, Subterranean Magazine is now available for free on its website; Issue 8 will be the last print edition and subsequently will move exclusively on-line, apparently with regular weekly updates of new fiction and columns, as opposed to a single fixed issue publication. Obviously, it’s less expensive to publish on-line than hard copy, though exactly why they are giving away content is unclear. The printed magazine was sold for $6 an issue, with a special “collector’s limited edition” hardcover sold for $80. (Interestingly, if you do a Google search, you can find issue #4 available for free as a PDF file.)

I have no insight into what the business rationale for this might be, other than to guess the magazine wasn’t sufficiently profitable and that perhaps the on-line version is intended as a way to get readers to visit the site regularly and possibly in a frame of mind to order the somewhat pricey limited edition books from parent Subterranean Press. What you get on the website is strictly text, no illustrations (though the magazine was never heavily illustrated) and no advertising. The stories are mostly “short-shorts,” though there are longer ones published in installments (as I write this, all twelve parts of the Lucius Shepard novella, “Vacancy” are up, and the first chapter of “The Surgeon’s Tale” by Jeff VanderMeer and Cat Rambo has been posted).

From the online version I took a look at “Missives from Possible Futures #1: Alternate History Search Results” by John Scalzi (who previously edited the magazine’s “SF clichés” themed issue). Ironically, it satirizes a popular Internet business model of supplying sample web content as a way to entice you to pay the full subscription fee. In keeping with our consideration of Dickian themes, it also, as you can tell from the title, pokes fun at the entire subgenre of alternate history. Scalzi presents eight possible timeline scenarios conjured by a research firm that might have happened had Hitler died in 1908 by various differing circumstances. Mildly amusing.

Not as amusing to me, is “Boiler Maker” by R. Andrew Heidel. Guy walks into a bar. Some philosophy about the meaning of life is exchanged between the patron and barkeep. What that meaning may be, not to mention the meaning of the story itself, eludes me.

Of more interest is Poppy Z. Brite’s “Wandering the Borderlands.” The narrator is a New Orleans coroner. She is used to dealing with dead bodies. But these bodies come to her having made the transition from vibrant flesh to a deteriorating collection of organs. What she is not used to is being the presence of those making the transition from a living thing to a dead one. That is her fear. That is, after all, everyone’s fear.

The Heidel and Brite stories aren’t really genre — there’s nothing fantastical or science fictional about their premises, although the narrative style is somewhat like the hard-boiled cynicism of noir fiction. Joe R. Lansdale’s “Surveillance” returns us to the time-honored tradition of science fiction as warning, depicting a Big Brother perhaps-nearer-than-we-would-like-to-think future where nowhere we go and nothing we do is unobserved. Well, hardly nowhere, at least until that gets fixed by those acting for our own good so there is “nothing left to fear.”

What readers need not fear is the easy access to short fiction, in print or on-line, at least in this reality.