Short Fiction Review # 20: “Unbound” from GUD 4

For this edition of my irregular review of the latest (more or less) short fiction, I thought I’d try something a little different. Usually I try to focus on the stories that worked the most for me, with maybe some attention on those that didn’t and why; at the same time, I also try to convey a flavor of everything else, if only just to alert you that an author is in the publication without, for any number of reasons, wanting to get into discussing the story to any great length. Note the use of the word “try.” One of the challenges here is to provide some substantive, possibly even useful, discussion to an audience that I’m assuming hasn’t already read the material. As noted elsewhere here in the Black Gate blog, that’s a distinction between literary criticism, which assumes knowledge of the work and doesn’t worry about spoilers, and a review, which is still critical (not just in the sense of pointing out flaws), but, out of necessity, less fully detailed.

For this edition of my irregular review of the latest (more or less) short fiction, I thought I’d try something a little different. Usually I try to focus on the stories that worked the most for me, with maybe some attention on those that didn’t and why; at the same time, I also try to convey a flavor of everything else, if only just to alert you that an author is in the publication without, for any number of reasons, wanting to get into discussing the story to any great length. Note the use of the word “try.” One of the challenges here is to provide some substantive, possibly even useful, discussion to an audience that I’m assuming hasn’t already read the material. As noted elsewhere here in the Black Gate blog, that’s a distinction between literary criticism, which assumes knowledge of the work and doesn’t worry about spoilers, and a review, which is still critical (not just in the sense of pointing out flaws), but, out of necessity, less fully detailed.

The job as I see it is to do justice to two or three stories of note for how good — or bad — they are, while at least acknowledging the existence of other contributions in a publication that might contain works from five, ten or even more writers. Consequently, the “hit and miss” approach is unavoidable. Frequently, I feel that in trying to do justice to the entire publication, I short sheet individual content. So, this time around, I’m going to focus on just one story, “Unbound” by Brittany Reid Warren, which leads off issue four (really the fifth, since the inaugural issue was #0) of the twice yearly GUD (aka Greatest Uncommon Denominator), as exemplifying the pub’s literary new wave fabulist, paraspheric, interstitial, elves-need-not-apply ethos.

I’ve been guest-blogging (with fellow Pyr author

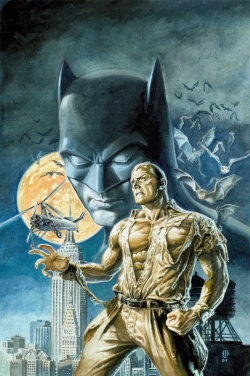

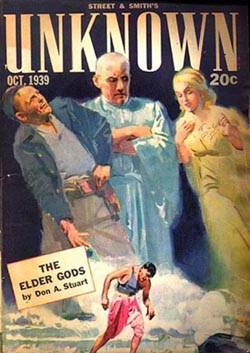

I’ve been guest-blogging (with fellow Pyr author  The comic book superhero was born in the late 1930s, during the time when the dominant form of popular culture reading was the pulp magazine. During the next decade, the pulps would start their slow demise: wartime paper shortages that forced the publishers to cut back on the more risky material to focus on the steady sellers, the paperback influx competed on the genre scene and were popular with soldiers overseas, and the rise of the comic book took away much of the younger readers. That the comic book should play such a large part in the end of the pulp magazine industry is an ironic reversal, since the hero pulps fueled the creation of those first four-color superheroes. No Batman without the Shadow. No Superman without Doc Savage.

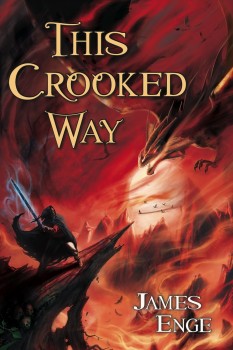

The comic book superhero was born in the late 1930s, during the time when the dominant form of popular culture reading was the pulp magazine. During the next decade, the pulps would start their slow demise: wartime paper shortages that forced the publishers to cut back on the more risky material to focus on the steady sellers, the paperback influx competed on the genre scene and were popular with soldiers overseas, and the rise of the comic book took away much of the younger readers. That the comic book should play such a large part in the end of the pulp magazine industry is an ironic reversal, since the hero pulps fueled the creation of those first four-color superheroes. No Batman without the Shadow. No Superman without Doc Savage. James Enge’s Morlock stories have been some of the most popular fiction we’ve published in Black Gate. His first Morlock novel, Blood of Ambrose, published by Pyr in April, was very warmly received, and described as “A future classic… this novel succeeds beautifully” (The Great Geek Manual) and “Like Conan as written by Raymond Chandler” (Paul Cornell).

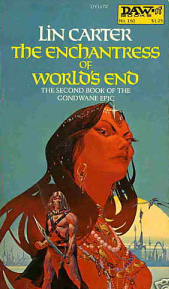

James Enge’s Morlock stories have been some of the most popular fiction we’ve published in Black Gate. His first Morlock novel, Blood of Ambrose, published by Pyr in April, was very warmly received, and described as “A future classic… this novel succeeds beautifully” (The Great Geek Manual) and “Like Conan as written by Raymond Chandler” (Paul Cornell). Linwood Vrooman Carter (1930-1988) was one of the heroes of my youth. In the decades since his death his reputation has wallowed in the aftermath of the Last Great Sword & Sorcery Boom. He helped start it, with the Conan books he and L. Sprague de Camp brought back into print, edited, and in many cases wrote, as with the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series of works he edited and thus brought back into print. (Not adult fantasy as in sex, but adult fantasy as in great classic works that weren’t kid stuff). Books by Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith and James Branch Cabell; title I never would’ve read in a million years otherwise, but books which shaped the tastes of many another fantasy enthusiast, myself among them.

Linwood Vrooman Carter (1930-1988) was one of the heroes of my youth. In the decades since his death his reputation has wallowed in the aftermath of the Last Great Sword & Sorcery Boom. He helped start it, with the Conan books he and L. Sprague de Camp brought back into print, edited, and in many cases wrote, as with the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series of works he edited and thus brought back into print. (Not adult fantasy as in sex, but adult fantasy as in great classic works that weren’t kid stuff). Books by Lovecraft and Clark Ashton Smith and James Branch Cabell; title I never would’ve read in a million years otherwise, but books which shaped the tastes of many another fantasy enthusiast, myself among them. I’ve been in reviewer overload lately, reading, taking notes, and penning reviews for the next issue of Black Gate. But, more than that, I’ve also been coordinating our crop of reviewers this time out, and thinking in terms of what exactly it is that ought to be in the review section of the magazine, not just in the reviews I put up on my own website. Having done over 50 reviews in the last year and a half or so, I think I’ve learned a few things, and I’d like to share my thoughts on what a good review should consist of. And at the end of this essay I’ll also offer some practical advice to anyone that wants to become a web reviewer themselves and share the reasons behind just why someone would want to take the time to review a book in the first place.

I’ve been in reviewer overload lately, reading, taking notes, and penning reviews for the next issue of Black Gate. But, more than that, I’ve also been coordinating our crop of reviewers this time out, and thinking in terms of what exactly it is that ought to be in the review section of the magazine, not just in the reviews I put up on my own website. Having done over 50 reviews in the last year and a half or so, I think I’ve learned a few things, and I’d like to share my thoughts on what a good review should consist of. And at the end of this essay I’ll also offer some practical advice to anyone that wants to become a web reviewer themselves and share the reasons behind just why someone would want to take the time to review a book in the first place.

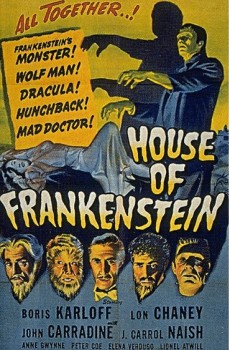

House of Frankenstein (1944)

House of Frankenstein (1944) Fans of Tom Waits are often divided into two camps: those who favor the early boozy Kerouac, be-bop inspired crooner of life’s derelicts and losers up until he transmogrified beginning with the “Heartattack and Vine” album and “crossed over” into Kurt Weill cacaphonous orator of the absurd; fans of the later period sometimes disdain the earlier, and vice versa, despite the obvious connections. Me, I’m in the third camp as a huge admirer of both milieus. (I suppose there’s a further quarter of people who can’t stand Waits at all, but, much like the folks who still tiresomely maintain Dylan hasn’t done anything since his protest days, aren’t worth serious attention.)

Fans of Tom Waits are often divided into two camps: those who favor the early boozy Kerouac, be-bop inspired crooner of life’s derelicts and losers up until he transmogrified beginning with the “Heartattack and Vine” album and “crossed over” into Kurt Weill cacaphonous orator of the absurd; fans of the later period sometimes disdain the earlier, and vice versa, despite the obvious connections. Me, I’m in the third camp as a huge admirer of both milieus. (I suppose there’s a further quarter of people who can’t stand Waits at all, but, much like the folks who still tiresomely maintain Dylan hasn’t done anything since his protest days, aren’t worth serious attention.)