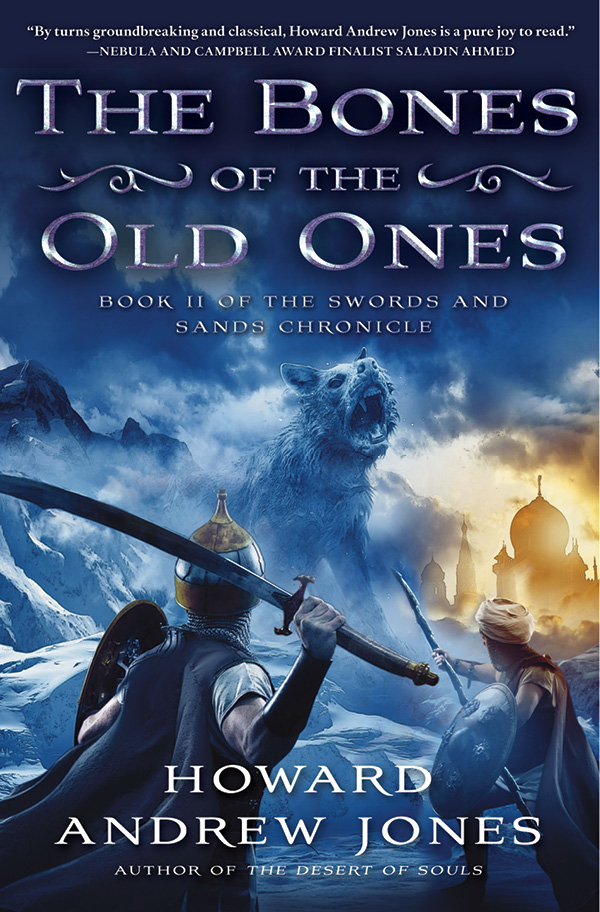

Black Gate Online Fiction: An Excerpt from The Bones of the Old Ones

By Howard Andrew Jones

This is an excerpt from the upcoming novel The Bones of the Old Ones by Howard Andrew Jones, presented by Black Gate magazine. It appears with the permission of Thomas Dunne Books and Howard Andrew Jones, and may not be reproduced in whole or in part. All rights reserved. Copyright 2012 by Howard Andrew Jones.

Chapter One

The snow banked knee-high against the walls of the narrow alley, and my boots sank into it as I pressed my back to the cold stone. I quieted my ragged breath and listened for the footfalls of my pursuers. They could not be far behind.

The snow banked knee-high against the walls of the narrow alley, and my boots sank into it as I pressed my back to the cold stone. I quieted my ragged breath and listened for the footfalls of my pursuers. They could not be far behind.

Thankfully the snow-clogged streets were already churned with footprints this morning; I was certain those who sought me lacked the expertise to identify my own.

Before long I heard the sound of snow mashed beneath swift, eager steps. I crouched to ready my weapons. Ambushes come down to timing, and I meant to judge my moment with care.

The footfalls stopped, then shuffled without advancing. My mind’s eye had one of them turning a circle, just beyond my hiding place.

Their leader spoke in low, urgent tones. “The captain has to be close. Rami, you go that way. Sayid, you come with me.”

One of his followers waxed confident: “We’ll get him this time!”

I had dressed for the weather, with multiple robes, a cloak, and even gloves. As I was never a small man, I cut an imposing figure so bulkily garbed. When I leapt into the street, roaring defiantly, two of the three youths jumped back in alarm. The other dropped a snowball at the same moment I launched my own.

“Fly, dogs!” I cried, laughing. My first strike caught Imad, the deep-voiced thirteen-year- old, in the dead center of his chest. While he looked down in surprise I grabbed another missile from those cradled in my arm and flung again.

“Run!” Imad shouted, his voice breaking. He dashed away, little Sayid fleeing with him. I tagged his retreating back with another cast even as Rami ducked into the doorway to the jeweler’s house.

“Ho, young one!” I advanced, one snowball brandished. “Prepare to meet your doom!”

Rami did not run; nay, the brave lad stood his ground and threw. His aim was near perfect, and caught me in the chest. At the same moment, I heard Imad and Sayid let out battle cries behind me, and I whirled. Their blows struck me in chest and shoulder even as I countered, laughing. It was then a frosty missile hit the back of my head. I felt my turban sliding toward my left ear.

“Ah!” I feigned sudden weakness and let my arm fall so that the snowballs rained about my boots. I clutched at my breast with both hands. “The lion falls!” So saying, I sank to one knee, then dropped into the snow. I lay rigid as a dying hero on a tapestry while my youthful companions cheered and cavorted with joy.

Their voices stilled at the same moment I heard the crunch of someone else approaching through the snow. I peered up to see my friend Dabir grinning at me, his blue eyes twinkling with amusement. He cradled a snowball in one hand. “Will you live?” he asked.

I sat up on the instant, adjusting my headgear. “What are you doing here?”

“This is the most direct route home from the palace.”

His grin widened as he saw the expression on my face. The caliph himself had ordered me to ensure the scholar’s safety by day and by night, but Dabir took a more casual approach to the arrangement. When last I’d seen him, he’d been sitting at a brazier in our receiving room, reading over some old Greek text. He had promised he would remain there.

Dabir dropped the snowball, and extended his hand. “No one was going to attack me, Asim. Captain Tarif came to get me.”

That made me feel only a little better. He helped me to my feet.

“Where is he now?” I asked, suspecting already the answer I would receive.

“Oh, I walked back on my own. Tarif had more important things to do.”

I sighed as I stepped back to brush snow from my robe.

Dabir smiled good-naturedly at the gathered children, but they could only stare back, shyly, even little Rami, our stable boy. They all regarded him with a certain amount of awe, for they knew him as a famous scholar and master of great secrets, someone to be treated with pronounced formality.

After a moment Rami worked up the courage to speak. “That was a good shot, Master.”

Dabir chuckled. “Thank you, Rami.”

“That was you?” I asked.

“You made too fine a target,” Dabir explained. “What say you to a meal? Are you hungry yet?”

I was, in truth, for I had taken a long morning walk before joining the snowball fight. Thus I bade the children farewell. They were sad to lose me, and in truth I was somewhat reluctant to quit, but Dabir was clearly set on continuing alone if I did not go with him, and as usual he had not even bothered to buckle on a sword. And besides, the cook’s fine pastries were now firmly in my mind. She was a harridan, but I could not dispute the excellence of her food.

So Dabir and I started for home.

Mosul was old… old almost as the Assyrian ruins that lay across the river, but not derelict, and sometimes showed a haggard beauty, for her stones had been set with care. Aye, her builders had been artisans as well as laborers, so that there were pleasing patterns in the brick and mortar.

On that day, though, it was as if she had donned an enchanted cloak that restored her youth. Even plain features to which I normally paid no notice — the heights of buildings, the bricks of walls, twisted old tree limbs topping garden enclosures — were mantled in white and transformed into sparkling works of art. It brought a smile to my lips as we walked.

“What did the governor want?” I asked.

Dabir turned over a hand as we walked past the homes and shops that lined the streets.

“Ah, Shabouh has him worried. He keeps going on about the positions of the stars and bad omens.”

I rather liked the pudgy court astrologer, but Dabir was skeptical of the man’s auguries.

“He swears that this snowfall was foretold,” he went on, “and that some old Persian star chart predicts even greater misfortune.”

I frowned. That certainly sounded alarming to me. In truth, the blizzard that had struck Mosul three days before defied any experience in living memory, so a little concern was perfectly justified. “What did you tell the governor?”

“Well, I did not wish to dispute Shabouh, but it seemed unwarranted to worry the governor over isolated acts of nature. I told them I would take a look at the records in the university. By the time I’ve compiled a listing of all the unusual weather in the last hundred years, the snow will have melted and all this will be a charming memory.”

“Do you think so?”

Dabir laughed. “Aye. When I was boy a great frost came to Mosul in early fall. It was so cold that ice formed over part of the Tigris. But it all melted by midday. Strange storms happen from time to time, and it is nothing to wring hands about.”

In light of what befell in the coming days, you will not be surprised to learn that I reminded him of that pronouncement for years after, but I get ahead of myself. At that time I merely groaned a little at the thought of spending the day watching him read texts in the cramped university library.

“I did not say that I would look today,” he added, clapping me on the back. “I plan instead to enjoy a nice game of shatranj near a warm brazier with my friend Asim.”

Soon we reached home, and after a pleasant meal we sat down in the receiving room and set up the shatranj board. We had moved but a few pieces when Rami pushed through the door curtain. He was ruddy-faced from the chill and panting from exertion. “I have found a woman in the street,” he gasped.

Rami’s sudden arrival set smoke from our brazier dancing above the cherry-red coals and introduced a blast of cold air seasoned with the scent of horses and manure, for the smell of the stables clung to him.

Dabir paused with his hand over the checkered board between us, the emerald on his finger glinting. “A dead woman?” he asked.

“Nay, Master.” Rami breathed heavily.

“You sound as if you have run a very long way,” Dabir said patiently.

“She was being chased,” Rami explained, “and begged me for help.”

“Chased by whom?” I asked.

Rami shook his head. “She would not say. She was very frightened.”

“Most like,” I said, “you have found a thief.”

“Oh, she is not a thief, Captain,” Rami assured me. “She is dressed like a noblewoman. She talks like a noblewoman. And,” he added, as though it were the most conclusive proof of all, “she is very pretty.”

Dabir coolly arched an eyebrow at me before turning over another of my pawns. “And you have left her in the stables?”

Rami froze, then nodded, his wind-burned face reddening still further. He lowered his eyes.

Dabir must have recognized the boy’s discomfiture, for his next question was very gentle. “What sort of help do you think she needs, Rami?”

The stable boy brightened. It was not every day he was invited to provide counsel for a great scholar. “There is something wrong with her, Master.”

His voice rang with conviction. “I think someone has placed a spell upon her.”

“Do you?” Dabir managed to sound not the least bit condescending. “Very well, then, Rami, bring in your mystery lady. I will see her.”

Rami grinned and backed out of the room, bowing formally. This sober exit might have been more impressive if we had not heard him immediately thereafter scamper down the hall at great speed.

Dabir turned back to me and grinned.

I shook my head. “That boy thinks wizards and efreet lurk behind every doorway.”

“Who shall we blame for that?” Dabir asked. “I was not the one who told him about the ghuls, or the lion, or that thing formed all of eyeballs. The cook said Rami had nightmares for a week.” He waved fingers at the board. “It is your move.”

I grunted. Buthayna had told me the same thing, but likely with more venom. I studied the pieces with care, although I had lost focus upon the game — never wise when playing against Dabir. We were just beyond the opening array and he was already commanding or threatening most of the board’s central squares. “This may all be some trick to ask alms from you,” I said.

“You are so skeptical, Asim. You should try to keep an open mind. Besides, if this woman needs money, I shall give some to her.”

He’d kept his eyes on the board and crinkled them only a little, but I knew he said this to bait me; for some reason my opinion of his financial practices amused him. In the ten months since our arrival in Mosul he had wasted cartloads of money upon an immense collection of old books and scrolls, and yet had not bothered to furnish all the rooms within the house.

I was still trying to decide whether to take Dabir’s central pawn with my knight or to advance my left chariot when there came a muted screech from a nearby room. I raised my head in alarm before recognizing the cook’s voice, and the lower answers of Rami.

“I should have guessed that,” Dabir said. “Rami has brought her in through the kitchen.”

I nodded.

“Likely,” Dabir said, his head tilted to listen, “Buthayna questions the poor boy’s wisdom in bringing an unattended woman into the house.”

“She will blame me.”

“Surely not.”

“Watch,” I said. “She will blame me, for she cannot blame you.”

“Hmm. What shall we wager?”

The answer came quickly to me. “If I am right, you will take up sword practice again this week.”

Dabir was a passable swordsman, but possessed the reflexes to be far better. He seemed always to find some other thing to do than join me for morning drills.

He nodded after a short moment of reflection. “Done. If you are wrong, you will try again with that text.”

I stifled a groan. “The one where the Greeks are sulking at the siege? That’s hardly fair. I’m trying to better you.”

“I swear by the Ka’aba you would like it if you continued! You gave up before you reached the battle scenes.”

“I suppose,” I said, for I did not expect to lose.

Footfalls hurried toward us from the room adjacent even as I spoke, and within a moment the curtain was pushed smartly aside.

Buthayna entered, bowing her head to Dabir. Like Rami she brought cold air, but with her came more pleasant scents — onions, cabbage, bread.

She was thin and stooped, with great gray wiry eyebrows. Many women her age dispensed with veils, but hers was thick. I think she meant the cloth to demonstrate her piety, although, as I had glimpsed her, once, veilless, it might be that she wore it as a favor.

“Master,” she said, her voice deceptively sweet and creaking with age, “my nephew says that you have told him to bring a woman into the house to speak with you.”

“This is true,” Dabir answered.

Buthayna’s eyes shift ed to me with a hard look, then back to Dabir.

“She has no attendants,” she persisted.

“Does she look dangerous?” Dabir asked with great innocence.

“She does not, Master, but she is alone.” She emphasized this last word as if he had somehow overlooked this crucial point. “Perhaps Rami did not convey all of this information to you?”

“It was clear,” Dabir said. “But the woman may need our help. We will see her.”

Again I received a look. I fully believe that Buthayna expected me to intercede to help her maintain proper decorum in the house. But I did not speak.

Dabir broke the silence: “Perhaps, Buthayana, it would be best if you accompany our guest.”

The cook’s yellowish eyes widened in surprise, then, apparently satisfied, she bowed her head. “As you wish, Honored One.”

The moment she disappeared through the curtain Dabir smirked. “I will bring you the Iliad by midday prayers.”

“Ah, ah,” I countered. “You could see from her look that she found me at fault. And you intervened before she could fully speak her mind. You, friend, need to dust off your sword.”

“But she —” Dabir fell silent as the curtains were pushed aside once more.

Buthayna poked her head through, then held the curtain open for another. “Master,” she intoned formally, “this is Najya. She has not provided me with her last name,” she finished, her voice laced with unspoken rebuke.

I had expected to be presented with a slattern in gaudy jewelry and bright fabrics, young enough to still be pretty. But our visitor was the very image of those aristocratic Persian beauties who walk with high-held heads through the court of the caliph. She not only looked the part, she had dressed it. I had been at pains to examine things more closely, as Dabir had taught me, thus I observed that the sleeves of her white gown were minutely frayed and the downward- pointing red flowers embroidered upon it somewhat faded. Likely they had been purchased from the castoff s of a real noblewoman, but they were certainly convincing enough to fool a boy.

Even her movements were practiced, from her graceful entry to her dignified consideration of the room as she probably checked for our most expensive items. In those days, most of our mementos — displayed in niches Dabir had ordered built into our south wall — were peculiar rather than valuable, like the false efreet head and the mummified lion’s paw, so it was not long before her gaze dropped to us.

Here I momentarily forgot my suspicions, and I would challenge any man who ever saw Najya’s eyes to swear they were not arrested by them.

Orange- brown ornaments, they were, that sparkled above her thin veil. Two perfect eyebrows arched above them, black like the long straight hair that crowned her more regally than jewels. She was no common thief.

We climbed to our feet. “Welcome,” Dabir told our visitor. “Please be seated, and take your ease. Rami has told us that you need help. Buthayna, please join us.” He gestured the cook to a nearby cushion.

Buthayna lowered herself slowly to the bare floor beyond the rug, as though determined to set an example of servile propriety.

I carefully pushed the shatranj board to one side and retreated to Dabir’s left , standing against the far wall as the others took their seats. I did not put my hand to my hilt, but I was ready to do so at need.

Our visitor bowed her head to Dabir. She spoke, her voice formal and precise. “I thank you for your welcome.” She paused, looking at the checkered board, seemingly to gather her thoughts. “And I apologize for interrupting your game. In truth, I hope only that you might be able to recommend a reputable caravan master.”

I thought then that we must be dealing with an actress who also could imitate the sound of wealthy folk.

“I know several,” Dabir answered. “Why do you need one?”

“I wish to return home.”

“You are from Isfahan?” Dabir asked.

She looked sharply at him. “How did you know?”

“From your slight accent; then there is the imperial crown flower pattern woven on your clothing, and the decorative detail upon the toe of your boot. They’re both popular among the aristocracy near the Zagros mountain range.”

She stared at him now with wary appreciation. “Your boy said that you were an accomplished scholar, but I thought he exaggerated.” Her head rose and she addressed Dabir formally. “You are correct. Isfahan is my home and I would very much like to return there as soon as possible. If there is anything you can do to assist me in finding safe passage, I would be grateful.”

I thought then that she would ask for money. She did not, though, and I realized she meant Dabir to volunteer it, which he would surely do.

Dabir rubbed the band of his ring with his thumb, his habit when lost in thought. “You have no protection, and little money,” my friend said after a time. “And unless you have some other belongings hidden in my stables, you have no traveling clothes. You are poorly prepared to venture cross country in this weather, especially as the men who kidnapped you are almost certainly still combing the city.”

“How —” Her startled eyes swept over to me and meaningfully to my sword. She rose as if to leave, looking frightened and angry at the same time. “Do you know them?” she demanded of Dabir.

I was almost as disconcerted as she. If Dabir was right, as he usually was, I had completely misjudged her; it seemed she deserved my compassion rather than suspicion.

Dabir glanced up at me, then at the cushion at my feet, and I inferred that he meant me to appear less imposing.

Thus I took a seat beside him. Do not think I relaxed my guard entirely, though.

“I know nothing of your kidnappers,” Dabir explained. “But, given your station, the condition of your raiment, and the markings upon your wrists, it seemed the most likely explanation for your presence in Mosul.”

She eyed him doubtfully.

“Please be at ease.” He motioned her to the cushion at her feet. “Why don’t we start over. I am Dabir ibn Khalil and this is Captain Asim el Abbas.”

Though I commanded no one there besides an adolescent stable boy, Dabir generally introduced me with the rank I held when we’d met.

She did not sit, nor retreat, though she seemed less likely to flee. Dabir carefully pulled at the fine gold chain about his neck and brought up the rectangular amulet normally hidden by his robes. He lifted it over his head and held it out to her.

“Dabir and I have sat at the right hand of the caliph,” I offered. “We are no friends to kidnappers.”

Hesitantly she took the thing and I saw her eyes rove over the gold lettering engraved there, commending all to respect its bearer, an honored citizen of the caliphate and friend to the caliph himself. Well did I know the wording, for I myself wore one, and it was a mark of esteem given to but a handful of men.

Her worry lines eased a little, and she looked up to consider Dabir in a new light.

“You have not told us your family name,” Dabir said. “Is there someone we may contact for you?”

She lowered herself onto a cushion slowly, regaining some of her composure.

“I am Najya binta Alimah, daughter of the general Delir al Khayr, may peace be upon him.” Her head rose minutely, but proudly, and with good reason, for the general had been well-known in his day as a brave defender of the eastern border. “As to those who follow me…” Her lovely brow furrowed. “Their leader is Koury, and he commands powerful men.”

“Is he, also, from Isfahan?”

Najya shook her head. “I do not think so. I had never seen him before, or the one he called Gazi. The speech and manner of both are strange.”

“Gazi,” Dabir repeated, and I knew from his more serious tone that the name meant something to him. “What do Gazi and Koury look like?”

Najya thought for a moment. “Koury is tall with light eyes. His hair is graying, and he has a noble manner. Gazi is…” Her lips pursed beneath her veil. “He is a dreadful man. He is short and broad but swift . He smiles often but it is not a pleasant sight.” She, too, had deduced that Dabir recognized the names. “Have you heard of them?”

“They sound familiar,” Dabir admitted. “Why did they take you from Isfahan?”

“I think they wanted me to find something, but I know not what. Or why.”

“To find something?” Dabir asked, puzzled.

“That is what they were talking of when I came around. They thought I knew where something was.” Here she paused, as if uncertain how to proceed.

Dabir glanced over to me before encouraging her to continue. “Perhaps it would be best if you tell us what you remember. Start with the kidnapping.”

Najya breathed deeply. I sensed that she gathered not her memories, but her courage. “My husband and I were walking to the central square in the evening,” she said tightly. “We heard footsteps behind us, and then a demand that I come.”

“Who demanded?” Dabir asked.

“The man I learned later was Gazi. My husband drew his sword and fought them, but they…” Her voice trailed off and she did not speak for a time. When she spoke again her tone was low and dull. “He was killed.”

It sounded as though there was more to be learned about the battle, but Dabir did not ask further. “I am sorry for your loss,” he told her.

I usually remained silent when Dabir questioned folk for information, but a comment from me seemed appropriate this time. “As am I.”

She glanced only briefly at me, then bowed her head slightly to us in acknowledgment. “Gazi fought as no warrior I have ever seen,” she added.

This in itself was an unusual observation from a woman, and the look I traded with Dabir did not go unnoticed by her. “I have seen many bouts,” she explained defensively. “My husband was an officer, my father a general.”

Dabir nodded. “Go on.”

“I tried to run, but Koury’s men were too fast. Too strong. They covered my eyes and forced a drink upon me. A sour drink. I did not swallow but it burned my mouth and I grew weak. The world spun for a long while.” She shook her head, troubled. “I really only have a few vague memories from then until I arrived here.”

I could well believe that she was the daughter of a military man, owing to the clarity and precision of her account.

“What happened when you arrived in Mosul?” Dabir asked.

Her look was sharp. “You mistake me. I do not remember entering the city. Suddenly I was upright and conscious in the street. Koury was there, talking with me — as though he had been speaking for a while and I should know exactly what he meant.”

“What was he saying?”

Again Najya shook her head. “There was some talk of finding a bone. I pretended I understood him, and when we neared the palace, I fled into the crowd.”

“A bone?” Buthanyna repeated, incredulous.

No one acknowledged her; it was not her place to speak, and she seemed to realize her etiquette breach because she shrank lower, as if to disappear.

“And that was when you found Rami,” Dabir prompted.

“Yes.”

“How long ago was this?”

“No more than an hour. Less, I think. Your boy was very brave,” she added. “He led me through a number of back streets. I do not think Koury could follow.”

“Let us hope.” Dabir looked as if he might say more, then asked, “How many pursue you?”

“In the square there was only Koury and two of his men. I did not see Gazi,” she added. “But Koury’s guards are incredibly strong. And there is something odd about them.”

“How do you mean?”

“They dress all in black and their faces are hooded. They do not speak.”

Dabir sat back and played with the band of his ring. And I studied Najya, mulling over her peculiar story. I could not fathom why someone would kidnap a Persian beauty, take her to a distant city, and command her to search for a skeleton, yet her very manner marked her as a speaker of truth.

“I think it best if you stay hidden for a while,” Dabir decided. “Please consider this your home until we can arrange for safe escort to Isfahan.”

She started to protest, but Dabir cut her off. “This is very important, Najya. Have your husband or family ever had dealings with magic, or its practitioners?”

I saw her lips part beneath her veil. After a moment, she shook her head. “No. I don’t think so.”

“Have you ever heard of the Sebitti?”

Again she shook her head. “No. Why?”

“It’s an old group with warrior wizards named Gazi and Koury. But I do not think it can be them.” Dabir said that last almost to himself. “Buthayna, see that she is given the guest suite, and please find a servant to attend her. One who can be trusted not to gossip, for our guest’s location must be secret.”

While the cook curtly acknowledged Dabir’s directives, I groaned inwardly. There was little more in the suite than a mattress and an old chest. It was hardly fitting accommodation for a noblewoman.

“You have been very kind,” Najya said, rising.

“It is nothing,” Dabir assured her. “Give me leave to look into the matter. You will be safe here, this I swear.”

“I would like to send word to my brother, in Isfahan,” Najya told him.

“Certainly. Buthayna, see that she has what she needs, and have Rami ask after a caravan bound there. He can start at the Bright Moon.”

“Yes, Honored One.” Buthayna rose stiffly and led the way through the curtain.

Najya turned to look back at us once more, then bowed her head and followed Buthayna.

“Who are these Sebitti?” I asked quietly as their steps receded. “I have never heard you mention them.”

“Why should I speak of fables?” Dabir frowned. “A mentor — a friend, really — was fascinated with them, and I recall only the broadest details.”

He shook his head. “I just don’t understand why a ring of murderers and kidnappers would name two of their members after them. These aren’t common names.”

I felt a growing sense of unease. “You haven’t answered my question.”

Dabir’s expression was still troubled. “You have heard of the Seven Wise Men?” he asked. “The Seven Sages?”

“Aye. Who has not?” They were famed for their knowledge of all matters, both arcane and mundane, and legend held that folk in need, if they be of pure intent, could find them to ask advice.

“They are the Sebitti.”

“I’ve never heard them called by that name.”

“It is from old Ashur. Their legend was born in that ancient time.”

“So these kidnappers have taken the names of wise men?” Now I understood Dabir’s confusion, and laughed. “If they meant to intimidate, wouldn’t they assume a more frightening alias?”

“I think you’re confusing wise with good. The people of Ashur, brutal as they were, dared speak of the Sebitti only in whispers.”

I had learned a little of the folk of Ashur, who some call the Assyrians, and knew they had been a warrior people, ruled by blood-mad kings. Anyone who they feared must be dangerous indeed. Thus I began to feel a vague foreboding. “Why?” I asked.

Dabir’s voice was grim. “They believed that when the lord of the underworld grew displeased, he sent forth the Sebitti to slay both beasts and men so that they might be more humble.”

I tried to imagine the gentle, and sedentary, wise men of legend riding forth with swords and chuckled.

“So you understand my interest,” Dabir finished.

“I do, but I don’t understand your aim. If the lady has been kidnapped, we should turn her over to the governor or a judge, don’t you think?”

He mulled this over, then shook his head. “Her story intrigues me…”

His voice trailed off, and I thought for a moment he would explain further, but he did not.

Dabir’s curiosity could lead him down dangerous paths. It was true that I felt badly for the woman, who would have to bear the shame of what had happened, and it was true that the circumstances were peculiar, but I did not see that our involvement was especially useful to her. And then another thought dawned upon me, one that I did not voice. Dabir mooned still for his lost love, Sabirah. He seldom spoke of her, but often stared at the emerald ring she had given him. It would surely be good for him to focus on another woman, and this Najya was a pretty one. Perhaps his interest had been piqued in more than one way.

I nodded as if his arguments made sense. “What do you mean to do?”

“I will make inquiries. Harith the innkeeper. Some of your friends in the guard. Captain Fakhir, or Captain Tarif. Surely one of them has heard of a kidnapping ring or strangers to the city matching these descriptions. Our guest strikes me as being quite memorable.”

I had feared for a moment that he would be dragging me to one of Mosul’s universities. “That does not sound nearly as bad as I had thought.”

Dabir stopped in midstride, where I’d followed him into the hall. He turned with a knowing look. “You will stay here, and guard the woman.”

Now that I did not care for. “The caliph charged me with guarding you,” I reminded him. “You keep forgetting —”

“Asim, Najya is in far greater danger than I. If the kidnappers track her to the house, who will defend her? Buthayna? Rami? You must stay.”

At the shake of my head, he added, “I will be careful, and I will return, or send word, by midday prayers.”

There was clearly no moving him, and I couldn’t argue that the woman needed no guard, so I merely frowned at his departing back and set to securing the house.

The caliph’s largesse had afforded us a spacious building on a corner in a quiet neighborhood. There were three entrances: that off the main street, the stables that opened onto a side street, and the servant’s entrance in the wall. This last I had insisted be boarded up when Dabir purchased the place, for with merely two servants we had no need of a special door.

Most homes in Mosul lacked street-level windows, and ours was no different, though the second floor boasted several. I made sure that all of these shutters were barred and warned Buthayna to admit no one, then crossed the courtyard to inspect the stables.

The outer doors I locked from within, and all else seemed in order, so I returned in under a quarter hour, only to have the cook emerge from the shadows and press something toward me.

“One of your soldier friends brought this,” she croaked. The object crackled in her hands as she shook it, and I recognized it for a sealed letter.

“Which friend… wait, how did you get this?”

“It was delivered.”

I paused before speaking, lest I say something I might regret, while she returned to her cooking pot and began to stir. Though the rest of our home might be sparse, we had an exceptionally well-furnished kitchen, and one built inside the home, a luxury unavailable to most. Buthayna had gleefully claimed it as her own once she joined us from the governor’s staff.

“I thought I had made clear,” I said, once I regained my composure, “that the door was to remain closed and that only I was to answer it.”

“So you did, but someone was at the door, and you were out in the stalls, so what was I to do?”

I felt my blood boil, yet did not curse. “Buthayna, you are not to open the door today unless it is Dabir, or this servant girl he wants to attend our guest. Do you understand?”

“As you wish.” She turned back to her doings.

“If I am out in the stables, or up the stairs, you are to come and find me.”

“As you wish,” she repeated carelessly.

“Now who delivered this?”

“That big soldier from the palace.”

“Abdul?”

“The polite one,” she growled pointedly. “Yes.”

“Thank you,” I said as pleasantly as I could, and left her.

I returned to the sitting room and studied the brown paper in interest. The seal was familiar, for it had come from my former master in faraway Baghdad. Jaffar had sent letters addressed to the both of us in the last year, but this one was labeled solely for Dabir.

I am not a petty man, but I was rankled that Jaffar had not seen fit to put both our names on the letter so that I might straightaway read his news. Dabir and I had both, after all, been his servants, I for far longer.

Likely it had merely been an oversight, but I would make no assumptions. I was still frowning down at the thing when there came a rap at the door. I sighed, tucking the missive into my robe, rising quickly lest the cook decide to ignore me once more.

She shouted at me from her den. “There is someone at the door, Captain!”

I advanced to slide back the eyehole, thinking to find the servant girl she’d sent for.

Instead I saw a tall, silver- haired gentleman with light-green eyes. Behind him stood two men garbed all in black, with deep hoods.

The kidnappers had arrived.

Chapter Two

“I have come for my daughter,” the fellow told me in a deep, stern voice. I could not quite place his accent, although it sounded a little Persian. “I have been told that you have her.”

I was rarely a quick thinker unless a weapon was in my hand, and I was momentarily troubled by his assertion. Might he have the truth of it, and Najya be the liar?

“Open the door and return her to me immediately,” he continued, “or I shall call forth a judge.”

If he meant to threaten me with mention of a judge, he surely had no idea with whom he spoke. Dabir and I were not only honored by the caliph, we were sometimes cup companions with the governor of Mosul. “Who are you?” I asked.

He glared, giving the impression he could see more than my shaded eye through the little opening, and I studied him in greater detail. I saw one unused to bending to any man. Indeed, he held his head as though he were accustomed to instant obedience. He was slim and straight-backed and as tall as myself. His beard and the hair that showed beneath his turban were gray, but here was no old man, rather one who had prematurely silvered. His thick robes, finely trimmed, must have warded him completely from the cold, for he looked not the least bit uncomfortable.

“I am Koury ibn Muhannad,” the fellow said, his breath steaming.

“Do you intend to speak to me from behind the door?” The disdain all but dripped from his voice.

I slammed home the eye slot, then opened the door and stepped forward to fill the portal. My size did not seem to trouble this Koury.

“I am Asim el Abbas,” I said.

“And do you have my daughter?”

I checked his men. Neither of them wore weapons or moved forward.

Neither of them, in fact, moved at all. Both stood with their left arms raised to belt level at the same angle, their right hanging at their sides. I knew not what to make of this, unless they were especially disciplined soldiers whose master desired a uniform presentation.

Koury awaited reply.

My oldest brother, Tariq, may peace be upon him, once told me that each time you lie you foreswear a little of your own soul. As a boy I had accepted his words without question; as a man I better understood his meaning. Some lies are surely necessary, but I strove always to avoid them.

“It is true that a woman has come to ask help of my friend, the scholar Dabir,” I said. “She may or may not be your daughter.”

He nodded once, and his eyes were calculating. “The mystery can easily be solved. Bring her to me that we may see one another.”

This was such a reasonable suggestion I was not sure what to do with it. I found myself stalling that I might gain more time to think. “What does your daughter look like?”

“She is well dressed, and very beautiful, with black hair and large brown eyes. Is this the woman who came to you?”

Instead of answering, I asked, “How did you lose her?”

Koury’s mouth narrowed to a thin line, but he replied. “She is a girl of wild notions since her poor husband was murdered before her. She grew frightened in the marketplace and fled.”

Surely the man looked wealthy enough to be Najya’s father, and he even had an explanation ready for Najya’s strange story — except, of course, that Najya had claimed to be the daughter of a famous, departed general.

“If I might see her,” Koury pressed on, “we can quickly clear this matter up. I might even agree to reward a man who has given my daughter shelter. I am prepared to be very generous.”

His words, sensible enough, were belied by a hardness of tone and manner that showed no fatherly warmth. Rather he sounded as if he viewed the woman solely as a commodity.

“Perhaps a judge would be useful after all,” I concluded.

Koury’s nostrils flared; one of his eyebrows twitched. Behind him both of the guards shift ed their gloved left hands at the same moment.

“Sometimes,” he said, his voice low, “men interfere in matters better left alone, through lack of understanding.”

I merely nodded and held my place. “That is surely true.” Then, by way of dismissal, I added, “Good day to you.”

His lips drew up in a sneer; I stepped back and closed the door, immediately dropping the locking bar into place.

I stood a moment, listening for them. Koury said nothing more, and neither of his servants spoke to him, but I clearly heard them crunch away through the snow.

For some reason I discovered that my heart beat rapidly, as if I’d just sparred with a lethal foe. I put my right hand to my chest to feel its speed, wondering that I should be so affected. When Najya spoke behind me I nearly jumped.

“Are they gone?”

I turned. “Aye.”

“They will return,” she said darkly. “I must leave.”

There were three doorways off the entry, and she was backing toward the one to the left.

I held up a hand to her. “You need not fear. Even if he finds a judge to hear him today, none will act without hearing first from Dabir.”

She shook her head quickly. “You don’t understand.”

“You are safe here.” I spoke slowly, for emphasis.

“No,” she said more forcefully. “Were you not listening? Did he have his men with him?”

“Aye,” I started to say more, but she cut me off.

Her eyes blazed. “My husband fought the both of them, striking them again and again, and doing them no harm. They would not fall. They cannot be hurt. And God help you if he also has Gazi with him, for that man fought circles around Bahir…” Here she paused, and her voice fell away.

“My husband,” she finished needlessly.

“Perhaps he did not strike deeply,” I suggested, hoping it was true, “and Koury’s guards wear armor beneath their robes.”

“Captain!” She spoke now with great force, as though she meant to strike me with words until I took her seriously, “Bahir was skilled and daring, yet Gazi cut him to pieces.” Moisture glistened in her eyes, though her voice did not falter in the slightest. “They cannot be stopped and everyone here will die!”

“Now there you are wrong.” Something in my manner brought her eyes firmly to me, as if she saw me clearly for the first time. “I have faced stranger things than these and come out alive. I will not let Koury take you. This I swear upon my life.”

Her answer showed more restraint. “I do not wish it to come to that.”

“It shall be as Allah wills, but that does not mean I intend to wait for the sword stroke on my neck. Dabir will shortly return, and I can guess that he will wish us to ride straightaway for the governor. Let us make preparations.”

She seemed calmer now, and unless I misjudged, she no longer saw me as an adversary. “You have great faith in your master. Is he, too, a warrior?”

“He is not my master, and his sword work is fair, though it is his wisdom we need most. Go to the upper floor and watch that corner.” I pointed to the southwest. “A man positioned there might see both the front entrance and the stable door.”

This must have seemed a good idea to her, for she started for the doorway to the dining room. “What are you going to do?”

I was unused to explaining my orders, but the question did not bother me overmuch. “I will have Rami saddle the horses. Then I will ready our gear. I’ll get you a traveling cloak.”

I was not sure what she meant by the searching look she bestowed upon me and there was no time to trouble myself over a woman’s thoughts. I turned away.

Rami, anxious to please, set eagerly to work. As to winter wear for our guest, Buthayna’s clothes would have been too small, and mine too large, so I raided Dabir’s wardrobe and took the steps to the second floor.

The upstairs consisted mostly of empty rooms — they were intended for an army of servants we did not have. From a shuttered window Najya showed me one of the black- robed men standing statue-still down the street, outside the home of Achmed the jeweler.

“He watches, just as you said. Though I know not how he sees,” she added.

His hood was deep and pulled low over his face, but it could be he sheltered his eyes from the glare of the empty white street and simply monitored with his ears. A thought occurred to me then concerning Najya’s previous description of the guard’s invulnerability. “Perhaps he is a kind of warrior ascetic. Some of them take drugs to render themselves insensitive to pain. It may be that your husband wounded them and they did not feel it, though they would have died later.” This sounded more plausible as I spoke it, and I added: “That might also explain how they stand so still.”

“They used some drug on me,” she said slowly. “I suppose they could have other sorts. Look. Isn’t that Dabir?”

I bent close beside her and could not help but breathe in a scent of jasmine from her hair. Sure enough, Dabir came swiftly down the road with that impatient, determined stride of his, heading straight to our door.

I bethought then of how I had said Dabir’s name to Koury, and I swear that my heart almost stilled when I realized there was no way I could reach him before the watcher should he choose to attack.

“Here is your cloak.” I shoved it into her hands and leaped down the stairs.

I flung open the door, hand to my sword, eyes set on the motionless watcher. Dabir came on, his brows raised questioningly at me. They rose even higher as I beckoned him to hurry.

The watcher did not move, and once Dabir was in I closed the door and slammed home its guard. I explained quickly all that had transpired while standing in the entryway, then Dabir fell to asking questions. At about that time Najya crept down the stairs and stood listening, the cloak still cradled in her arms.

“Did you note any smell about the robed men?” Dabir asked me.

“If they smelled, they were not close enough to detect anything.”

“What about you, Najya, when you met them?” Dabir faced her. “Was there any salty smell, or a strong herbal scent?”

“No. Why?”

“Just a thought. Asim, I think you have suggested a fine plan. If this fellow has gone to a judge, we shall go to a governor.”

“What did you find?” I asked.

“An inn near the Tigris where Najya and Koury and two others checked in last night. They boarded no horses.” Again he faced our guest. “Have you remembered anything further of arriving in Mosul yesterday?”

“No,” Najya answered.

“The innkeeper said that you were alert and deep in conversation with Koury until late in the evening.”

Her eyes widened. “I swear,” she insisted, “upon my life and the holy Koran, that I remember nothing of this.”

Dabir stared hard at her.

“I do not lie!”

Dabir nodded sharply, and I had the sense that he meant to question her more fully at a later time. “Let us go,” he declared.

“There is one more thing,” I said, and passed over the letter from Jaffar.

Dabir grew more concerned as he studied the wax seal. “What is this?”

“It was sent from the palace just before Koury arrived. It is from Jaffar, but addressed only to you, or I would have opened it.”

He broke the seal. I could not see the writing, but watched his eyes search the paper. A shadow of gloom crossed his face.

“Is all well?” I asked.

“Aye,” he said softly. “Sabirah has given birth to a baby girl, and both she and the child are healthy.”

“Praise God,” I said, heartily. “That is good news.”

“That is surely good news,” Najya added. “Is she your sister, or a cousin?”

“No.” Dabir folded the letter and tucked it away. “She is merely a former student.”

That was a minimal description, and I do not think it fooled Najya, but she did not press for further details. I tried to put a better face upon the matter. “It was kind of Jaffar to tell you,” I pointed out.

Dabir stared at me pointedly for a moment, as if unsure as to my meaning. “Yes,” he said slowly, without enthusiasm, then closed the discussion. “We must be going.”

Only a short while later, Dabir and Najya and I rode out from the stables, the woman mounted on our old cart horse, for we had no other animals.

Usually Dabir and I walked Mosul’s streets, which are frequently crowded in better weather, but we wished to outpace pursuit if it came to that.

I caught sight of the black-robed guard as we left , but he did not follow, or even turn to acknowledge our passing. I watched carefully but saw no sign of further monitoring or pursuit.

We diverted around the few, well-wrapped folk in the street and passed walled homes and shops, our life breath rising in wispy clouds. Before long we had neared the great square that lay before the governor’s palace, on the heights of the city at the end of a wide avenue that stretched the length of Mosul to the bank of the Tigris.

The governor at that time was Ahmed bin Hakim, a kind and generous man in middle age. He had been raised to office on a whim of the mad caliph, Haroun al- Rashid’s immediate predecessor, Allah alone knows why, and had proved so popular with the folk of the north that he had retained his position even as most other appointments were handed over to the current caliph’s adherents, which is to say allies of Jaffar’s family.

Though quite pious — Ahmed had made the holy pilgrimage twice — he was not one of those religious men who seek always to point out the faults of others. He loved a good story, good food, and, as I had seen, the grape, though it be expressly forbidden. In all other ways was he devout, most especially in almsgiving and in good works, and I think it was due to his nature rather than a desire for praise. Two nights before, to aid the suffering of his people in the cold, he had decreed that a fire must be kept burning in the square in front of the old fortress, and so a great bonfire had been erected. As Najya and Dabir and I rode in, a flock of beggars and indigent folk huddled before it in relative ease, under the watch of a few bored soldiers. If the great cold continued, God help him to find more wood and to afford its cost, but the governor, like Dabir, had no head for money.

As you might expect, cloth and food vendors quickly set up stalls and carts near the fire to partake of the free source of heat, and to prey on those who wandered by to deliver alms to the poor or those en route to the governor’s palace. With the merchants had come customers, and with them a few entertainers and game players, so that what had begun as an aid to the downtrodden had taken on new life as a street carnival complete with jugglers and stilt walkers, gamblers, and even wine merchants who lured in patrons with the promise that fruit of the vine inured one to the cold.

I did not care to ride into that shifting mass, where enemies might hide, but we had no choice if we wished to reach the palace. Scanning constantly for sign of ambush, I led the way, with Najya following and Dabir bringing up the rear. I fully expected to see danger before the others, thus I was startled to hear Najya call out in alarm just as we reached the far fringe of the throng. I turned on the instant to find one of Koury’s hooded men at her side holding her mount’s bridle. Koury himself was running up from a side street, his robe belled out behind him. The crowd turned to him as he called out in praise to Allah that his child had been found.

The cloak of Najya’s hood had shaken loose and her face was obscured by a wave of midnight hair that slung back and forth as she struggled against the hand that gripped one of her ankles. Her patient old gelding shifted in consternation.

My mare, Noura, answered smoothly as I turned her. “Let the woman be!” I put hand to my sword hilt, and at that moment I saw the other black robed man flanking me from the right.

Najya’s captor did not reply, thus I drew my sword. A nearby man gasped, and I heard mutters about me. The crowd parted.

Koury pushed his way clear and strode up to us. His smile was thin, his voice loud so that it would be heard by the onlookers. “Ah, thank you.” He raised his head sultan high. “You have found my wayward daughter.”

“That remains to be seen,” Dabir said shortly from my left. “Release the woman.”

The other black-robed man had halted on my right.

Najya addressed the crowd in her clear, commanding voice. “This man is not my father! Do not believe him!”

The murmuring intensified even as the encircling wall of onlookers widened.

Koury laughed theatrically and looked to Dabir. “You see the sort of fancies that she takes. She is a willful, spoiled girl, and I have only myself to blame.”

“This is a matter for the governor,” Dabir declared. He looked only at Koury but pitched his voice loud enough to carry to the crowd.

Koury’s expression hardened. “I am beholden to no man for her fate.” He bared his teeth and lowered his voice. “She is mine.”

“Not at this time,” Dabir responded sternly. “You’d best have your men leave off.”

“You heard Dabir.” I pointed my sword at the man on the left . “Release her.”

This he did not do. He took one hand from the nag’s headstall and effortlessly dragged Najya from her saddle as she shouted in protest and struggled in his clutches. The other charged my horse and struck out with a gloved fist. He connected, hard, and blood sprayed out from a gash near Noura’s nostrils. She screamed in anger and pain even as the madman lunged at me.

“Dog born dog!” I cried, trying to steady my outraged mount. I did not know how a man might draw such blood striking only with his hand. Somehow he avoided Noura’s dancing and grabbed hold of my boot with stiff fingers.

I leaned from my saddle to shroud the idiot by cleaving his skull.

My blade bit deep into his head, but the strike felt wrong. Those of you who have never brained a man with a sword — and may it please Allah that it be most of you, for there is altogether too much braining of men in this world — will not know that there is a distinct difference to the way a blade feels when wielded against a skull as opposed to most other objects. My blow caught in the fellow’s head as if I’d sliced into a stump. He did not fall with splayed limbs and spraying blood. He did not even flinch. Even were I wearing a helmet I would have shown some reaction to having sharp metal bounced off my crown. Yet from him there was nothing. A cold dread certainty gripped me as I pulled my weapon free. This was no warrior ascetic. I faced dark sorcery.

Read the rest of the exciting tale in The Bones of the Old Ones, on sale Tuesday, December 11!

Available for pre-order by clicking here (scroll to page bottom).

When not helping run his small family farm or spending time with his amazing wife and children, Howard can be found hunched over his laptop or notebook, mumbling about flashing swords and doom-haunted towers.

When not helping run his small family farm or spending time with his amazing wife and children, Howard can be found hunched over his laptop or notebook, mumbling about flashing swords and doom-haunted towers.

He has worked variously as a TV cameraman, a book editor, a recycling consultant, and a college writing instructor. He was instrumental in the rebirth of interest in Harold Lamb’s historical fiction, and has assembled and edited eight collections of Lamb’s work for the University of Nebraska Press.

Howard is also the author of The Desert of Souls, Pathfinder Tales: Plague of Shadows, and the short collection The Waters of Eternity. His stories of Dabir and Asim have appeared in a variety of publications over the last ten years, and led to his invitation to join the editorial staff of Black Gate magazine in 2004, where he has served as Managing Editor ever since. He blogs regularly at the Black Gate web site and maintains a web outpost of his own at www.howardandrewjones.com.

5 thoughts on “Black Gate Online Fiction: An Excerpt from The Bones of the Old Ones”