An Interview With Pulp Novelist David C. Smith

By Jill Elaine Hughes

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

David C. Smith, now a professional scientific manuscript editor living near Chicago, published nearly twenty novels of pulp fantasy in the 1970s and early 1980s, including several volumes in the acclaimed Red Sonja series. Smith’s novels — now mostly out of print but still widely available on the secondhand book market — represent a bygone era in science fiction/adventure fantasy writing and publishing.

David C. Smith, now a professional scientific manuscript editor living near Chicago, published nearly twenty novels of pulp fantasy in the 1970s and early 1980s, including several volumes in the acclaimed Red Sonja series. Smith’s novels — now mostly out of print but still widely available on the secondhand book market — represent a bygone era in science fiction/adventure fantasy writing and publishing.

With the recent mainstream publication of such bestselling novels as Paul Malmont’s The Chinatown Death Cloud Peril (Simon & Schuster, 2006), old-style pulp fiction is enjoying a bit of a renaissance, and might mean that old-school pulp authors like Smith, who largely left publishing in the mid-to-late 1980s as both the American publishing industry and the American public’s reading tastes changed, could return for a “second act.” Chicago-area freelance writer Jill Elaine Hughes recently sat down for an interview with Smith, where he revealed what it was like to be a successful pulp scribbler in the early days of pulp’s “second wave” in the ’70s and ’80s, writing under the tutelage of such legendary pulp authors as Edmund Hamilton and Leigh Brackett.

How many novels did you publish in the “pulp” genres? With which publishers? Tell me a little about these books.

How many novels did you publish in the “pulp” genres? With which publishers? Tell me a little about these books.

Eighteen, primarily from 1977 to 1983, with a couple more in 1989 and 1991. Most of these wound up being parts of series. My idea initially was that I wanted to write historical novels or perhaps thrillers, but because sword-and-sorcery was so popular in the early ’70s, I wrote a couple of manuscripts in that genre. That’s where I began to be in print and that’s how I was promoted and marketed. Unfortunately, sword-and-sorcery, that masculine kind of adventure-fantasy writing, never really became a legitimate genre. I saw it then as another genre, like Westerns and mysteries, but it didn’t take hold. There’s a lot of fantasy being published now, but I think that it’s grown more out of role-playing games and corporate agendas. In the early ’70s, these sorts of stories were still a continuation of the pulp writers of the ’30s, ’40s, and ’50s.

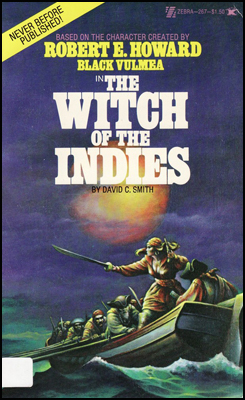

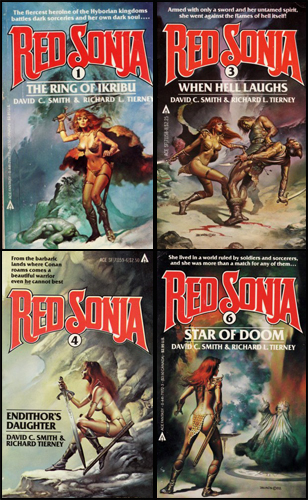

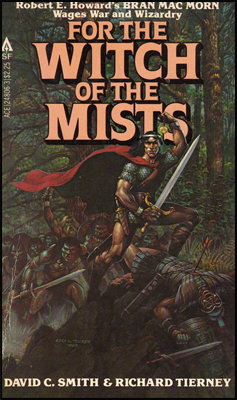

The first two novels I had in print were The Witch of the Indies (Zebra Books, 1977), a pirate story, and For the Witch of Mists (Zebra Books,1978), a story about the Picts fighting the Romans. They were both based on characters originated by Robert E. Howard. His Conan stories had been reprinted in the ’60s, and there was a real Howard boom in popular publishing in the 1970s. So I was hired to write those. I wrote For the Witch of Mists with Dick Tierney. He’s a few years older than I am and had discovered pulp fiction in the pulp magazines when he was growing up in the ’50s. It was through Dick that I met my first agent, and he and I wound up writing the six Red Sonja books together a few years later. Red Sonja was a Howard character, too.

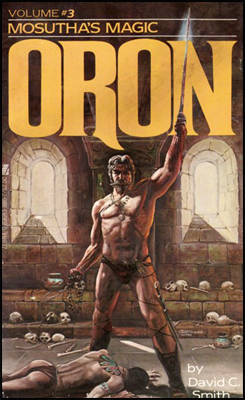

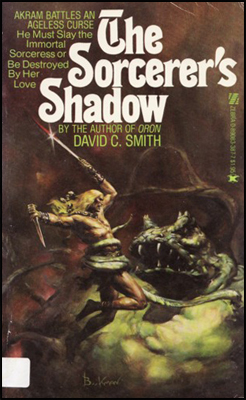

The first manuscript I wrote was Oron (Zebra Books, 1978). It was more adventure-fantasy, and it was on the strength of that book Zebra Books hired me to write The Witch of the Indies. I wrote some more books on that character, too (Oron) for Zebra Books. The Red Sonjas were for Ace.

A big fantasy trilogy, The Fall of the First World, was published in three volumes by Pinnacle Books in 1983. A few years later, Avon brought out The Fair Rules of Evil and The Eyes of Night, which are thrillers about a young seminary student who learns to practice sorcery.

Was it different writing “for hire” versus writing your own original characters/stories? Can you comment on how that affected your process?

Was it different writing “for hire” versus writing your own original characters/stories? Can you comment on how that affected your process?

The for-hire work that I did fit in very naturally with the type of fiction I was writing at the time, so it was not a great stretch for me to move from writing Oron to writing the Red Sonja novels, except that turning out the Red Sonja manuscripts on a schedule really taught me how govern my time and focus my skills. The other thing was that Roy Thomas, who’d developed Red Sonja for the Marvel comic books, had provided us with a kind of outline of dos and don’ts. It wasn’t a fully realized character bible but it gave us the ground rules, and what I found was that by having to stay within some prescribed boundaries, it challenged me so that I had to be as a creative as I could. There’s a kind of positive creative tension that occurs when you have to stay within bounds. I don’t know if it always works but I found that it worked for me with the Sonjas. I wrote the first drafts and Dick Tierney wrote the final drafts. That’s the way it was when we wrote the Bran Mark Morn story, too, For the Witch of Mists. It balanced out well.

What attracted you to writing “pulp” and “for hire” pulp of others’ licensed characters? Did you make a good living writing “for hire”? Did you find that it took away from developing your own original stories?

It was a natural extension of what I was reading at the time. A lot of pulp authors were reprinted in the late ’60s and early ’70s. I was in high school and college then and read everything I could get my hands on. I’d decided by my second year in college that I wanted to try writing seriously, to earn money at it. It grew out of reading these books and reprints.

I never consciously decided to write for hire. My agent in the mid-’70s set up the contracts for the books based on the Robert Howard characters. It coincided with the material I was already writing, so it was a logical extension of that. So for that reason I didn’t feel any sense of conflict, but that’s because I also became typecast as a certain kind of writer. I never made much money at it, though.

Of the nearly twenty novels you had published during this period, which is your favorite? Why?

Of the nearly twenty novels you had published during this period, which is your favorite? Why?

The Fall of the First World. And the David Trevisan books — The Fair Rules of Evil and The Eyes of Night. The Fall was ahead of its time. It’s an historical novel, a trilogy about a fantasy world, so that world and those events didn’t occur but the book reads as though they did. Parts of it are almost documentary. What I wanted to write was a kind of fantasy War and Peace but set it in circumstances similar to the Third Crusade, when Richard the Lion Heart and Saladin were testing each other over Jerusalem. That was the genesis. But it grew into something much more, a kind of fountainhead of different elements that recur in Western myth and literature. So it’s the Iliad or the Franks versus the Saracens, but it’s also despotism versus enlightenment and similar concepts embodied in certain characters. Thameron is the priest who takes the easy way out, for the best of intentions, but becomes an agent of destruction and evil. Asawas is the enlightened man, a farmer who has a vision of universal truth and becomes a prophet. There’s a Wandering Jew character, and a Helen of Troy character. I deliberately borrowed these images and themes to create a kind of forgotten Ur-history of humanity. I’d still like to go back and polish it one more time, although it really does have some of my best writing in it.

Did you develop a fan base? What was your relationship with your fans? Did you ever get any of those weird, obsessive fans, the kind you see at some sci-fi conventions?

I’m lucky in that the readers who’ve gotten in touch with me have been pretty literate and intelligent. I never went to very many cons, just a few, because I was always working a day job, even when I was selling books. I should have gone; I neglected the business end of my work and I would have been able to talk to other writers and to editors. But I know the kinds of fans you’re talking about. The people who wrote to me, though, were like the young women in the early ’80s who wrote to thank us for writing the Red Sonja books because she was a strong female hero. I saved those letters. One fan named his daughter after a character in one of my books. Her name is Asya Kyler. He and his wife thought the name was lovely. There’s a Red Sonja fan down in Georgia named Sonja Cannon and she really is a red-headed Sonja. She works in the comics industry, I believe. The people who wrote to me all seemed to have something on the ball.

When Oron came out in 1978, another writer, Joe Bonadonna in Chicago, wrote to me. We’ve been friends every since. My sister and my aunt have adopted him, and he and I have collaborated, and my daughter has an Uncle Joe. I wouldn’t have had that otherwise.

Why did you decide to stop writing for the pulp market?

Why did you decide to stop writing for the pulp market?

A combination of things happened. I burned out in mid-1983 after writing a lot of material in a very short space of time to fulfill contracts that showed up around the same time. Also, I was not very successful. My manuscripts were published, but nothing more ever came of it. I call my success the worst string of good luck you ever saw. I was published early and I wrote a lot in a hurry, but I was very young. I relied too much on agents, which typically is like hiring wolves to guard the sheep. The real machinery never kicked in — no hardcovers, no foreign rights sold, no TV movies, no movie options. I think my stuff came out a little too early for that to happen. Now all of these things are integrated for writers, but that wasn’t the case back then. That developed out of the huge growth of chain bookstores and corporate mergers. I was signing books one afternoon at a bookstore in Ohio, I want to say around Salem or Alliance, this was in the late ’80s, probably in ’89 when Fair Rules came out, and I was talking to the manager. I told her that my first paperbacks were published without the bar code on the back. She said, “You were still published when they published books.” It wasn’t merchandise or consumerism or product or profit centers then, just storytellers and their readers. It sounds very quaint now, doesn’t it? Write an adventure story, have somebody pick it up off the rack in the bus station, read it on the road. That world is gone.

How is the “pulp” business of today (such as it is) different from the period in which you wrote?

I’m afraid that when I dropped out in the mid-’80s, I didn’t keep up with the field. Twenty years have gone by, and I haven’t paid much attention to how things have developed. I’m a medical editor now. You could draw a line on a timeline and it separates where I dropped out from where we are now. I stopped reading fantasy when I started publishing it in the late ’70s because I didn’t want to be influenced by other writers. Then as I got even busier, the spare time for reading dried up, too. And I never got it back, much to my regret. For a while there, when I moved to Chicago and I was taking the train to work downtown, I had glorious free time to read again. Now I fit it in when I can.

What kind of writing are you focusing on now?

I recently finished a book I’d wanted to write for years, Seasons of the Moon (iUniverse, 2005). It’s mainstream — literary, in fact. I’m working on another adventure-fantasy novel. That’s another one I started years ago, put it away, and now I’m working on it again. It’s literary, as well. Some friends of mine want me to go through my old fanzine short stories from the ’70s and tidy them up and publish them as a collection.

Did you have any important writing mentors? Who were they? What was their influence on you?

When I was just out of college I knew Edmond Hamilton and Leigh Brackett for the last few years they were alive. Mr. Hamilton graciously read some of my short stories; he asked to see them. I regret now that I didn’t show him Oron; it was in manuscript then. But he read five or six of my short stories and critiqued each one and gave me the best description I’ve ever heard of a story that works. He said of one of my stories, “This is good. It marches.” He’s right. You know from the first sentence whether or not the writer knows what he’s doing or what she’s doing, don’t you? The story marches.

If you could write any book and guarantee it would be published and sell well, what would it be?

If you could write any book and guarantee it would be published and sell well, what would it be?

Coincidentally, I’ve just written that book, Seasons of the Moon. It’s another story I worked on for years, off and on. It’s about a small society that practices the Old Religion, and the Old Religion is that women are sacred, women create life, the earth is our mother and she nurtures us, there is no revealed religion, that’s sophistry, but what we have is us and Mother Nature and our spirits, which are part of the natural world. I struggled with how to tell the story and when I decided to tell it through the eyes of the little boy, it gelled.

But to get back to your question, I’d like to write a Western sometime, but it would have to be accurate, you know, pass the muster of the people who really know the history of the West, and I don’t know if I could do it. I’m not sure I have any business writing a Western. But I’d like to write some more thrillers, anyway. I’m a big Hitchcock fan. There’s a bit of Hitchcock in The Eyes of Night.

Which pulp authors (of any era, including now) do you admire most?

Leigh Brackett. She was a writer’s writer and is still underappreciated. You can read her sentences and it’s as if she’s reading your mind and she’s anticipating what you’re thinking. A wonderful craftsperson.

Robert Howard, of course, especially his early stuff. It’s easy to make fun of Howard but if you show his stories, especially his early stories, to people who don’t know anything about him, they come back with a big smile because he’s the real stuff, a guy who worked very hard to master his craft and honed his natural gifts and became a good writer. The big regret is that we don’t know what he would have written when he was 50 or 60. He’d have been in Hollywood, I’m sure, writing movies for Howard Hawks alongside Leigh Bracket or selling books to John Ford.

Charles Saunders. He’s another writer whose stuff marches just beautifully. He and I were having our stuff published about the same time, in the mid-’70s, in Space & Time magazine. He writes about a character called Imaro, an African warrior in a kind of alternate-universe African continent. His stuff is just now being republished.

What do you think of the so-called “return” of the pulp genre, via such recent books as Paul Malmont’s The China Death Cloud Peril (Simon & Schuster, 2006)? Will that lead you back to writing more pulp?

See, here I am again. I dropped out. I don’t know Paul Malmont. I haven’t read this book. Friends of mine recommend books to me, and that’s how I discovered Christopher Moore and Carl Hiaasen. I keep trying to find more time to read, but now my wife and I just had our first child, our daughter, so when I do read things, I’ve got her in one arm and I’m reading a little bit at a time. But it’s wonderful. But I spend most of my time now copyediting orthopaedic surgery manuscripts.

Thanks for the shout-out, Dave! I didn’t know Jill interviewed for Black Gate. Very cool!