Feature Excerpt: “Building the Fantasy Canon: the Classic Anthologies of Genre Fantasy”

By Rich Horton

from Black Gate 2, copyright © 2001 by New Epoch Press. All rights Reserved.

Part One

Part One

It has become something of a cliche these days to note that popular fantasy seems to be concentrated in novels, and indeed in very large novels, or series of novels. A common acronym is FFT, for “Fat Fantasy Trilogy”. Probably the best selling current fantasy series is Robert Jordan’s The Wheel of Time, which now extends to 9 books, with the books close to 1000 pages each. Other popular series of recent years include David Eddings’ Belgariad, Robin Hobb’s Assassin, and Raymond Feist’s Magician. New entries, which have garnered considerable critical praise as well as sales, include James Stoddard’s House books, Steven Erikson’s new series beginning with Gardens of the Moon, and Elizabeth Haydon’s new series beginning with Rhapsody.

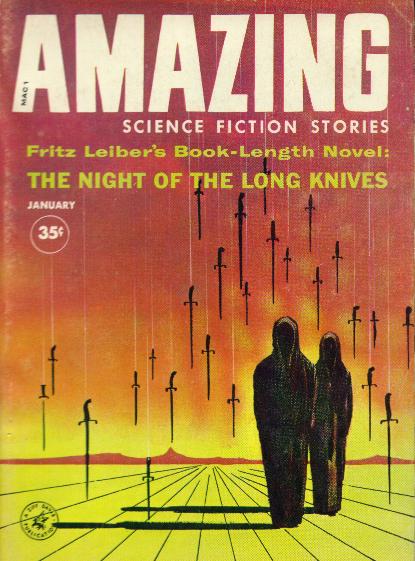

This is often blamed (or credited) to the influence of J.R.R. Tolkien. After all, The Lord of the Rings is a trilogy, isn’t it? (Actually, it’s not. It’s a fairly long novel which divides naturally into six books, but which was presented in three volumes due to the exigencies of the publishing business.) And certainly Tolkien’s first popular imitators, such as Terry Brooks (The Sword of Shannara and sequels), published long series of longish books. Even if we go farther back in time, Robert E. Howard’s Conan books, and Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser series, appear to the casual eye to be long series of novels, albeit comparatively short novels.

Fantasy’s sister genre, Science Fiction, is often said to be built on the short form. Short stories are called “the lifeblood of the field”. Though long SF novels and series of novels are certainly around, there is still an emphasis on the short form, and there are, for example, two prominent anthologies per year devoted to collecting the best Science Fiction (not Fantasy) short stories, while there is only half of a prominent Best Fantasy anthology. Is the Fantasy genre really best suited for the longer form? Are short stories merely a minor side branch of the river of Fantasy?

I don’t really propose to answer those last questions, except to say that whether or not short fiction is less commercially important to Fantasy than Fat Trilogies, there is a lot of fine short Fantasy available. Going back to the beginnings of Fantasy as a separate genre, and extending to this day, much influential work has been short fiction. I would view Lord Dunsany’s work, mostly at about 1500 words, a huge clutch of stories published starting in 1905, as second only to Tolkien in influence upon contemporary Fantasists. Moreover, much significant short fiction, by Howard and Leiber as well as by H. P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, and others, was published in pulps beginning in the 1920s: the most important of these pulps being Weird Tales. Still, to achieve permanence, stories really need to end up in books. In this essay I’ll review some of the great books, especially anthologies, now and in the past, where we can look to find that short fiction.

To begin with, one place to look is in some of the books published as novels. For example, Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser books are mostly composed of short stories, or very short novels, assembled two or three or more to a book. By the same token, most of Robert E. Howard’s original Conan stories were short fiction, later assembled into quasi-novels. The Conan publishing history is further complicated by the posthumous “collaborations” by Lin Carter and L. Sprague de Camp, in which the two writers took existing Howard stories and fragments and expanded them into novels. In addition, Jordan added a series of Conan books written on his own, which represented his first success in the field.

To begin with, one place to look is in some of the books published as novels. For example, Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and the Grey Mouser books are mostly composed of short stories, or very short novels, assembled two or three or more to a book. By the same token, most of Robert E. Howard’s original Conan stories were short fiction, later assembled into quasi-novels. The Conan publishing history is further complicated by the posthumous “collaborations” by Lin Carter and L. Sprague de Camp, in which the two writers took existing Howard stories and fragments and expanded them into novels. In addition, Jordan added a series of Conan books written on his own, which represented his first success in the field.

Early Anthologies

But my real interest is in the anthologies of Fantasy, especially those that might be regarded as attempts at “canon-building”. That is, anthologies that purport to preserve the best stories in some quasi-permanent form. In this forum, I’m particularly interested in those anthologies that appear to regard Fantasy as a separate genre.

Much like SF, (if anything, even more so), Fantasy is some form or other has been around for as long as stories have been written. But it seems only recently, perhaps since roughly the turn of the century, that it has been perceived as a separate genre. It’s tempting to date “genre fantasy” to the appearance of Dunsany’s stories, beginning in 1905, not because Dunsany was the first to write recognizable pure fantasy (certainly Morris and MacDonald were writing such a couple of decades earlier), but because Dunsany so clearly created a significant body of imagery and tropes that has been endlessly recycled since. Alternately, we might mention the appearance of Weird Tales in 1923. At any rate, by the time SF became a magazine genre (in 1926, with the founding of Amazing Stories), Fantasy was itself at least as much a genre.

But in ensuing years it was SF that seemed to dominate. In the early 1940s, Astounding Science Fiction had a companion magazine of fantasy, the very well regarded Unknown, but when Street and Smith needed to cut back due to wartime paper shortages, it was Unknown that was killed. In 1949 one issue of The Magazine of Fantasy was published, only to be changed to The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction with the second issue. But all along Fantasy stories were being published alongside Science Fiction stories, and to this day the two genres are regarded as “sister” genres. Science Fiction Writers of America changed its name to Science Fiction and Fantasy Writers of America to recognize the dual nature of the field. Both Science Fiction and Fantasy stories are eligible for both the Hugo and Nebula Awards (though the winners are overwhelmingly on the Science Fiction side of the divide, assuming one can place the dividing line reliably).

Speaking of the dividing line compels one to concede that it can be very fuzzy. There are several “canonical” examples of borderline cases. Consider Anne McCaffrey’s Pern series: stories about firebreathing dragons, but set on a far planet. The first Pern stories were even published in the “hard SF” magazine Analog. Or Jack Vance’s The Dying Earth and sequels: featuring magicians and spells, but ostensibly set in the very far future of Earth. Or Leigh Brackett’s books about Eric John Stark: originally set on Venus and Mars, she moved later books about Stark to the more openly “fantastic” planet Skaith, after the advance of scientific knowledge about our planets rendered the classic Martian settings too absurd for her to try to get away with. But for all that even the earlier Brackett books may be outwardly SF, they show clearly the influence of Dunsany. Indeed, much ostensible Science Fiction, or Space Adventure as it was often called, in magazines like Planet Stories, was SF only by courtesy, and these days would very likely be published as Fantasy.

Speaking of the dividing line compels one to concede that it can be very fuzzy. There are several “canonical” examples of borderline cases. Consider Anne McCaffrey’s Pern series: stories about firebreathing dragons, but set on a far planet. The first Pern stories were even published in the “hard SF” magazine Analog. Or Jack Vance’s The Dying Earth and sequels: featuring magicians and spells, but ostensibly set in the very far future of Earth. Or Leigh Brackett’s books about Eric John Stark: originally set on Venus and Mars, she moved later books about Stark to the more openly “fantastic” planet Skaith, after the advance of scientific knowledge about our planets rendered the classic Martian settings too absurd for her to try to get away with. But for all that even the earlier Brackett books may be outwardly SF, they show clearly the influence of Dunsany. Indeed, much ostensible Science Fiction, or Space Adventure as it was often called, in magazines like Planet Stories, was SF only by courtesy, and these days would very likely be published as Fantasy.

Still, fuzzy as the line is, most of us can draw it. And even as the first Science Fiction anthologies were appearing, in the 1940s, there were anthologies explicitly devoted to Fantasy. Donald Wollheim was among the earliest anthologists in both genres. A significant early series of Fantasy anthologies was Wollheim’s Avon Fantasy Reader series, which began in 1947 and ran to 17 numbers through 1951. (There was also a very brief run of Avon Science Fiction Readers, in 1951 and 1952, and after Wollheim left Avon, two all-original issues of The Avon Science Fiction and Fantasy Reader, edited by Sol Cohen, came out in 1953.) These were saddle-stapled paperback books, looking a lot like magazines, or like the Scholastic paperbacks I used to buy in my school days. The contents were all reprints. Wollheim mined Weird Tales for many stories, as well as selecting some of the more overtly fantastical stories from the Science Fiction pulps of the ’20s, ’30s and ’40s. He also reprinted stories from Lord Dunsany’s collections, and stories by other “pre-genre” writers like William Hope Hodgson, Frank Stockton, M. R. James, Stephen Vincent Benet, Ambrose Bierce, Algernon Blackwood, M. P. Shiel, and others.

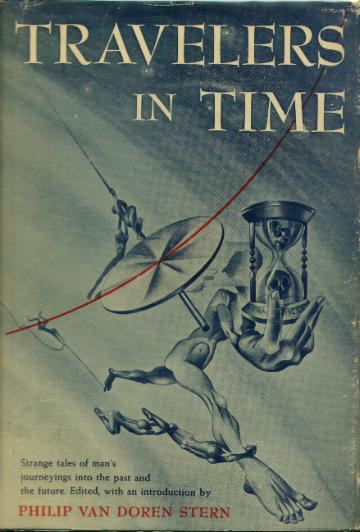

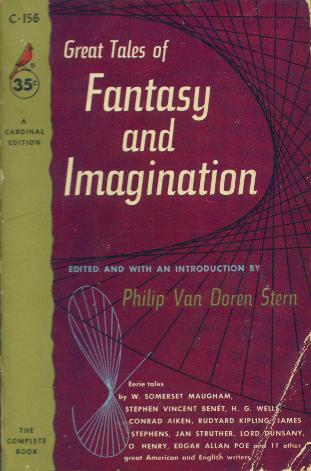

Other anthologies from the ’40s were even more solidly devoted to strange tales, more often than not ghost stories, from the pens of non-genre writers. Philip van Doren Stern’s The Moonlight Traveler (aka Great Tales of Fantasy), published in 1949, featured stories by Benet and Dunsany, of course, as well as such usual suspects as Edgar Allen Poe, Robert Louis Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling, O. Henry, and Saki, and such unusual suspects as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Conrad Aiken. But no stories from “genre” sources: “fantasy”, here, is still a sidelight, curios produced by mainstream writers. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, indeed it might be regarded as a healthy situation. Certainly one would be much less likely to see an anthology of ostensible Science Fiction from mainstream writers, even though the likes of Poe and Kipling, at least, occasionally wrote SF-like stuff. Another example is August Derleth’s 1947 anthology The Night Side, which collects stories by Walter de la Mare, MacKinlay Kantor, Arthur Machen and Lord Dunsany among others. But Derleth also ventured into genre sources, for stories by H. P. Lovecraft, Lewis Padgett, Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, and even lesser known writers. Derleth’s book, indeed, is an excellent example of an anthologist casting his net widely, ignoring neither excellent in-genre nor excellent out-of-genre work. Still, at this time there is no real sense of Fantasy as a separate genre, and indeed the titles of both anthologies hint that the real focus is on the “supernatural horror” aspect of Fantasy.

Other anthologies from the ’40s were even more solidly devoted to strange tales, more often than not ghost stories, from the pens of non-genre writers. Philip van Doren Stern’s The Moonlight Traveler (aka Great Tales of Fantasy), published in 1949, featured stories by Benet and Dunsany, of course, as well as such usual suspects as Edgar Allen Poe, Robert Louis Stevenson, Rudyard Kipling, O. Henry, and Saki, and such unusual suspects as F. Scott Fitzgerald and Conrad Aiken. But no stories from “genre” sources: “fantasy”, here, is still a sidelight, curios produced by mainstream writers. There’s nothing wrong with that, of course, indeed it might be regarded as a healthy situation. Certainly one would be much less likely to see an anthology of ostensible Science Fiction from mainstream writers, even though the likes of Poe and Kipling, at least, occasionally wrote SF-like stuff. Another example is August Derleth’s 1947 anthology The Night Side, which collects stories by Walter de la Mare, MacKinlay Kantor, Arthur Machen and Lord Dunsany among others. But Derleth also ventured into genre sources, for stories by H. P. Lovecraft, Lewis Padgett, Ray Bradbury, Robert Bloch, and even lesser known writers. Derleth’s book, indeed, is an excellent example of an anthologist casting his net widely, ignoring neither excellent in-genre nor excellent out-of-genre work. Still, at this time there is no real sense of Fantasy as a separate genre, and indeed the titles of both anthologies hint that the real focus is on the “supernatural horror” aspect of Fantasy.

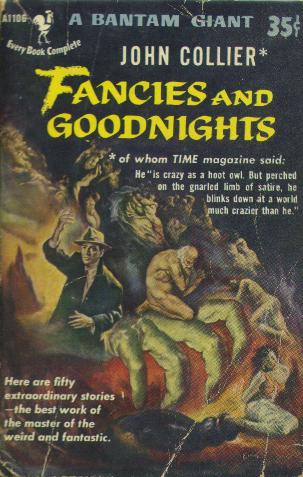

While in many ways Lord Dunsany and the Weird Tales writers, particularly Lovecraft, established significant models which are still imitated (often only too slavishly) in contemporary Fantasy, it is a truism of sorts that Fantasy as a separate genre, with commercial force all its own, dates to J.R.R. Tolkien, in particular The Lord of the Rings, as I suggest above. These books were published in 1954 and 1955. However, there is no obvious series of Fantasy anthologies dating to the 1950s establishing a “canon” of short fantasy fiction. The examples I’ve cited from the late ’40s and early ’50s are hardly prominent today, after all. Brian W. Aldiss did edit an anthology called Best Fantasy Stories, in 1962, which appeared only in England. This was a short book containing the usual sort of quirky mainstreamish pieces that appeared in the earlier books I’ve mentioned. Ray Bradbury, Angus Wilson, and Aldiss himself were contributors, as well as the remarkable John Collier, who wrote quite a few very original short pieces, many collected in Fancies and Goodnights. Collier was a wonderful writer, but in many ways he was sui generis, writing more in the tradition of Saki than in that of any fantasy writer.

4 thoughts on “Feature Excerpt: “Building the Fantasy Canon: the Classic Anthologies of Genre Fantasy””