Short Fiction Reviews: Fantasy Magazine and Interzone

A Look at Current Fantasy Magazines

By David Soyka

Copyright 2007 by New Epoch Press. All rights reserved.

Apple has just announced its highly anticipated iPhone and, whether you really need one of these things or not, you have to admit it’s pretty cool-lookin g. Of course, it doesn’t matter much if it doesn’t work as well as it looks. Apple wouldn’t be the success it is without its ability to match good design with content people want, like portable music players or easy-to-use computers.

g. Of course, it doesn’t matter much if it doesn’t work as well as it looks. Apple wouldn’t be the success it is without its ability to match good design with content people want, like portable music players or easy-to-use computers.

Genre publishing doesn’t always see the connection between design and content, however. The leading triumvirate — Asimov’s, Fantasy and Science Fiction and Analog — come in small, unattractive packages printed on cheap stock with minimal or no interior artwork and cheesy cover pages. One reason, of course, is economics. The argument goes that readers are more interested in quality stories than quality artwork. The counter argument goes that better design might attract more interest.

How may times have you bought a book just because of its cover? Maybe if they upgraded their design, perhaps Gardner Dozois wouldn’t ritually report decline in readership in his annual summation of the state of the genre.

Less Shine for Interzone

Interzone, Britain’s longest running science fiction magazine (as it says right on the cover), took precisely that tack when Andy Cox became publisher of what until then was one of Britain’s most graphically ugly publications. With the December 2006 issue, No. 207, the impressive design overhaul gets tweaked a bit, replacing glossy stock with matte paper, while retaining full color artwork and pictures. In his editorial, Cox says this was done for “readability,” but asks for reader opinions, so presumably there’s a chance he might switch back. Since you asked, Andy, I have to agree that I like the matte because it doesn’t reflect light as gloss does. But I also have to wonder if the primary driver here is perhaps lower cost. If so, it’s a win/win.

The magazine is also a little smaller, but Cox insists there’s more content than before despite the diminished dimensions. The one thing that does bother me is the magazine is now saddle-stitched instead of square-back; collectors who file issues on their bookshelves will find it annoying that they no longer can read issue contents on the spine.

As for those contents, the lead story by Dave Hoing is “The Purring of Cats.” It depicts the anguish of a therapist who crosses the ethical, but perhaps not human, line in the patient/therapist relationship. The patient’s crime against the state is that she has had sexual relations with an alien; the therapist’s ” crime ” is that he confuses her issues about intimacy with his own attempts to achieve it. An excerpt: “It’s unfortunate, but many people measure their lives in terms of their losses. I’m no different. Karen, my home, my things, my career, everything I once thought I needed. All gone over a flare of middle-age passion. I have only myself to blame. The pressure of the war is a convenient excuse, but what I did, I did willingly. I knew there’d be a price. There always is. Nikki will serve her time and I’ll serve mine. Hers is ten years in prison, mine a conscience which lasts for life. I can’t say whose punishment is harsher.”

“Spheres” by Suzanne Palmer, in contrast, has little concern with human psychology. Instead, she offers straight-forward space opera that wouldn’t have been out of place in a magazine designed during the 1940’s: a sort of trailer park in space has a new resident with an eye toward gaining some prime real estate through the death of the owner. Why the newcomer wants to move his spherical-shaped living unit into that of the narrator’s is the plot mystery, in which what goes around, comes around.

I’m not quite sure what to make of “Clocks” by Daniel Kaysen. A woman wakes up with a co-worker after a night of alcoholic imbibing. Not surprisingly, she has a blackout and can’t recall exactly how she ended up in his apartment, or what exactly happened between them, though she assumes they were intimate. This situation repeats. Until, that is, when she awakens in the same room with the same guy, but with the added dimension that now the guy’s wife is in the next room. And, she apparently is actually the guy’s sister — either because that’s what he’s telling his wife, or because she really is. This seems to have something to do with the prospect of pregnancy. But damned if I know why.

We get back to something more substantial with the contribution of David Mace. In John Brunner’s Stand on Zanzibar, a character asks, “What good is it to be human if it takes a machine to save us?” Mace’s “Frankie on Zanzibar” answers that the machines can’t even outsmart a clever kid, even if that kid is the product of genetic modification. Like Brunner’s classic novel, it’s a little hard to wade through what’s going on, which I’m guessing is part of Mace’s homage. Back in 1969, Brunner saw overpopulation and the resulting scarce resources as the primary threat to humanity; today, Mace perhaps more rightly emphasizes corporate power struggles, which operate independent of Malthus, further empowered by technology, though not necessarily any smarter.

The final story is more in keeping with Palmer’s in that it is not-so-hard-to-figure-out straight sf/horror that could have been a Twilight Zone episode. In Wendy Waring’s “Stonework,” an archeologist for CultuRecon is trying to determine the purpose of a temple-like structure on a now uninhabited planet. Trouble is, he gets too close to his work.

Better Looking Fantasy

Better Looking Fantasy

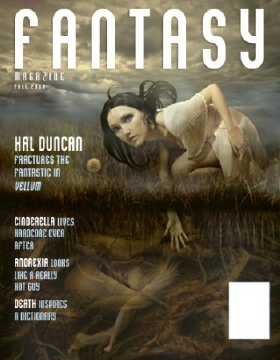

Fantasy, in its first year of publication, also does some fine-tuning of its appearance with issue No. 4, though nothing like Interzone‘s original ugly duckling transformation. New creative director Stephen Segal has cleaned up the interior type and artwork so it looks more like a magazine and less like a ‘zine. The cover page, which continues to feature some kind of faerie creature (could this be its version of the Playboy Bunny?), is cleaner, more modern. Color is added to the inside cover advertisements. Nothing overly radical, but a much nicer package.

A number of stories here are retellings, or reinventions, of classic fairy tales. Frequently this involves a feminist perspective, or transporting it into a modern setting (which Darren Speegle does with the Psyche myth in “Exposure”; see also Amber van Dyk’s “The Green Men” for a variation of the fisherman’s odd catch and the effect on his wife; another take on Greek mythology is how the gods copulate with mortal maidens without remorse for the consequence of their action — Catherine M. Morrison considers the story from the viewpoint of the raped, whose complicity in the seduction does not excuse the act in “Mushrooms Sprouting in Your Footsteps Like Tears”). One of the standouts is “After Midnight,” by Alison Campbell-Wise, a brutal riff on the Cinderella fable. I know, I know, this has been done again and again. But not like this. Positively shocking and disturbing, this inversion of the cruel stepsister trope has nothing to with fairy godmothers and happy endings, but the best and worst inclinations of people who are often not what they seem.

Also of interest is Ben Peek’s “Under the Red Sun,” which posits a Frankenstein culture in which the dead provide useful resurrection components. Those who, for reasons of faith or lack of it, wish to ensure they or their loved ones don¹t become part of the inventory must arrange for cremation. When the narrator’s mother insists on a Christian burial in the dirt for his sister, he and his brother comply, hoping to return shortly after the funeral to retrieve the corpse and protect it from grave robbers. They are too late, however, and in seeking to recover the body of his sister before the “surgeons” begin corporeal renovations, he discovers arrangements made that seem, well, unnatural.

Speaking of death, young children are sometimes depicted as having unusual insight to predict future events, particularly someone’s demise, that seems less scary to them than the adults. In “During the Dance,” Len Bain’s protagonist discovers this ability may be something that runs in the family. Which may not be a good thing.

“Alicia’s Prayer” is answered in Lisa Ann Figueroa’s tale of fertility wish-fulfillment. Unsurprising though perhaps interesting to Anglos, it is told from a Chicano perspective.

Marly Youmans employs the idea of a nesting doll as a narrative structure in “The Matreshka” to ponder the not-laughed-at physics theory that we may exist in multiple dimensions, with multiple outcomes.

In “Branson Rebellion,” Megan Messinger sprinkles a little fairy dust on a runaway slave railroad route to suggest that you can go home again if you understand the risks, and are willing to take them and endure the consequences.

“Irregular Verbs” by Matthew Johnson provides a neat little riff on Bradbury’s “The Illustrated Man” in which a bereaved widow of a linguistically inventive tribe epidermally preserves the meaning of the otherwise forgotten words of intimacy.

E. Catherine Tobler’s “Ticket to Ride” views intimacy from a more malevolent vantage, that of an immortal woman whose grief compels her to feed on the sorrow of others, to the detriment of those seeking relief.

Mosquitoes are known as carriers of disease, and in “Mosquito Story,” Afifah Myra Muffaz shows how the source of infection can stem from human desires for revenge. This setting is a little less outright fantastical, as is the setting of “Rosemary, for Remembrance” by Hannah Wolf Bowen, which depicts a man struggling to confront his guilt after causing a woman to lose her short-term memory.

Perhaps the most experimental story is “Why the Balloon Man Floats Away” by Stephanie Campisi. The titular character floats in various situations that confront the protagonist, evidently to represent the fragility of deep emotional situations that seem doomed to burst. Profound, I think, but with stories of this type you can never be sure.

I am sure of the powerful punch packed in Kaaron Warren’s “Dead Sea Fruit,” which presents a dentist as a sort of tooth fairy whose kiss turns girls into anorexics. The narrator has fallen in love with him, and he perhaps with her as he delays “infecting” her. The protagonist, however, chooses to remove the problem.

A number of these authors aren’t familiar to me; one who has generated something of a buzz, however, is Hal Duncan, who is the feature interview subject. I haven’t read “Vellum”, his debut novel, yet, but the interview does prepare me for what may be a difficult read. If the story he contributes here, “Bizarre Cubiques,” is any indication, I can understand why some folks have had trouble “getting him.” Duncan notes that he favors non-linear narrative and his story, as you might expect, mimics the fragmentation of cubist art. Indeed, the story seems to be about the narrator¹s reaction to “Cubique” art, which is presumably a parallel art movement in an alternative universe where “Pharis” is our Paris and a guy named “Bricasso” is presumably “Picasso.” I confess, though, that whatever particular design Duncan may have had here, it eludes me.