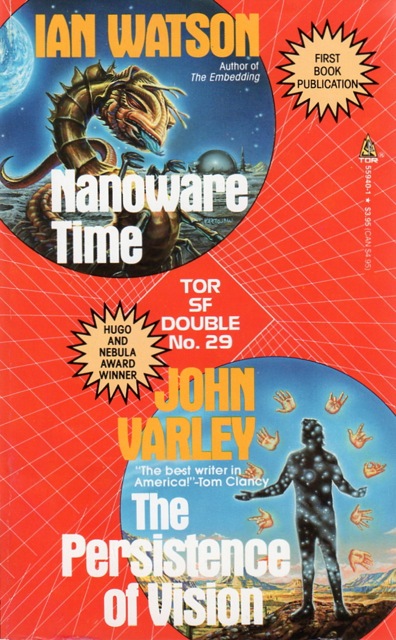

Tor Doubles #29: Ian Watson’s Nanoware Time and John Varley’s The Persistence of Vision

John Varley makes his third and final appearance in the Tor Double series in volume #29, which was originally published in January 1991. Ian Watson makes his only appearance in this volume.

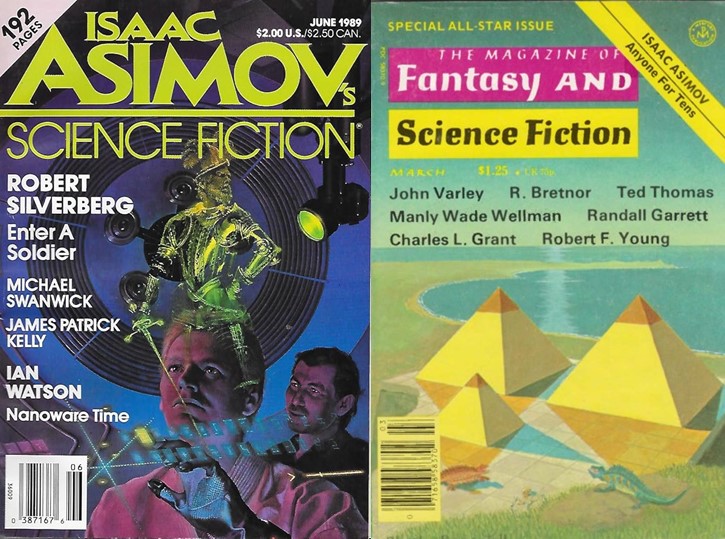

The Persistence of Vision was originally published in F&SF in March 1978. It won the Hugo Award and Nebula Award as well as the Locus poll. It was also nominated for the Ditmar Award.

Varley offers a United States which has gone through a series of boom and bust cycles. During one of the bust cycles, Varley’s narrator decides to travel from his native Chicago to Japan, but with the economy being the way it is, he isn’t able to take any form of public transportation, instead walking and relying on the occasional ride. Rather than heading straight west, he takes a more southerly route to avoid the radioactive wastes of Kansas and other Great Plains states.

While the novella opens with the background to explain the world in which his characters live, Varley provides only the briefest of background strokes, and ultimately, the world situation doesn’t matter to the story except as a means of getting the narrator to the location of the story. As he moves through New Mexico, he finds himself moving from commune to commune, each one an attempt to build a utopian society in the ruins of an economically devastated United States.

Each of the communes has its own issues and he only stays a few days before abandoning it and moving on to the next one on his quest to reach the west coast. Eventually, however, he comes across a commune that seems different from all the others and he quickly learns why. The commune of Keller is made up entirely of people who were born deaf and blind and their descendants. The inhabitants welcome him as a visitor and he comes to appreciate their culture as he learns more and more about it, revealing it to be the utopian society so many had striven for and failed to achieve.

The narrator’s entry into their society is through a young girl he calls Pink, the daughter of two of Keller’s founders. As one of the children born at Keller, Pink understands the strange language that is used in the commune, but is also sighted and can hear. Her knowledge of English, allows her to communicate with the traveler and explain to him the rules of Keller and how communication works there.

Communication is the key to the story and Varley describes a system which seems to be based on American Sign Language, but he quickly reveals that there are multiple levels of language, beginning with spelling things out, followed by touch, followed by an even deeper means of communication. As the narrator learned each level and realized there was a deeper level of communication, he became more and more enamored by the culture into which he was being admitted, always fearing that his role as an outsider would force him to have to leave.

In fact, he did jeopardize his stay, in part due to his sight. Living in a sightless community, one of the most important things is to make sure that everything is where it is expected to be, or perhaps even more importantly, not where it is not expected to be. When he accidentally leaves something in a pathway, causing injury to a woman he called Scar, he finds himself placed on trial, not fully understanding either the Keller legal system or the ramifications and punishments which could be coming his way. He does, however, accept responsibility for his actions, which is important in Keller society.

Although the novella doesn’t focus on it, there is an aspect of free love in the Keller society, with the line between communication and sex constantly blurred and the perpetually unclothed residents of Keller communicate by fully contact. The narrator must overcome his own view of sexuality as he learns that homosexuality and heterosexuality don’t have the same meaning or import within Keller, and sex is just another form of communication. This aspect of the story also proves somewhat problematic since this language is used by all the residents, no matter the age, and the narrator’s guide is Pink, who is in her early teens.

Eventually the narrator moves on, changed by his experiences at Keller, and constantly regarding that period of his life as a special one, even after he makes it to the West Coast and then on to Japan before returning to the United States. He manages to make a good living for himself, despite the frequency of “non-depressions,” and eventually is drawn back to his utopia, to find out how things may change over the years.

Varley’s three stories in the Tor Doubles series demonstrate a range. Tango Charlie and Foxtrot Romeo (TD#4) is set on an abandoned space station, Press Enter [] (TD#26) looks at computer hackers, and The Persistence of Vision (#29) offers a utopian society.

Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine May 1990 cover by Gary Freeman

Nanoware Time was originally published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine in June 1989. The version of the story appearing here is expanded. I’ll admit that 29 volumes in, I finally have come across a story that has me stymied.

It has been said that science fiction often needs to teach the reader how to read the story. If the author writes “he threw out his back” the reader doesn’t always know if it is a metaphor or an actual description of something physically happening. The further away from the mainstream the story goes, the more the story needs to guide the reader. In this, Nanoware Time doesn’t fully succeed.

Paul Royal is on his way to the moon after completing training in Alaska to participate in a project with an alien race known as Serpents. On his flight, he meets Kath Knox, whose own training took place in Greenland. The two of them hit it off, knowing that they are part of the same organization and once on the moon nanos would be injected into their system to give them increased abilities. They, along with the rest of the cohort, is heading to the moon because the powers that be want to make sure the nanos are safe in an isolated environment before they can be let loose on the Earth.

Once Paul and Kath begin their training on the moon, they learn that the nanos open up an inner space that is inhabited by beings that are referred to as demon, which is how the individuals infected with the nanos are able to harness their advanced powers. The demons, however, come with warnings on their use and there is a question about how sentient, obedient, and benign they actually are.

The story progresses in a relatively straightforward manner until a training accident leads the humans to question the program they are part of. However, it moves forward and Kath and Paul find themselves injected with the nanos, at which time, they go through a change and become part of what appears to be a discorporated army that can be used to fight in wars across the galaxy. Despite being part of a larger almost hivemind that can communicate, they also retain vestiges of their individuality and Kath and Paul maintain their relationship, along with forming a bond with Sweets, a nanoed version of another species.

Eventually, Kath, Paul, and Sweets begin to fight back against their overlords and try to learn more about the universe in which they are fighting and the causes they are defending, as well as trying to regain some autonomy. Part of the issue for the reader, however, is that while Watson made Kath and Paul sympathetic figures at the start of the novella, as they go through their changes, and as the novel’s style becomes more experimental, it is more difficult for the reader to connect to the characters.

There were times when it felt as if Watson was just stringing words together without any concern for whether or not they formed a coherent sentence or thought. This technique does appear to intend to communicate that the aliens and the altered forms of Paul, Kath, and Sweets have moved beyond a state of normal human comprehension, and the reader can either choose to go with the flow (or gloss over the words) or study them to figure out any specific meaning Watson was trying to convey.

The concept behind the story is reminiscent of Arthur C. Clarke’s Childhood’s End, in which the Overlords, an alien race, bestows boons on humanity, but remain hidden from view. In Nanoware Time, the Serpents allow themselves to be seen, but humanity questions how benign their gifts really are.

While I haven’t always loved the novellas in the Tor Double series, Nanoware Time was the first one where I was wondering what I was reading as my eyes scanned the page. Watson plays around with style, but if it gets in the way of comprehension too much, it ultimately fails. It is possible that Nanoware Time would benefit from a closer reading, but the payoff doesn’t seem like it is worth the time

Ron Walotsky provided the cover. This was the final volume to identify itself as a Tor Double on the cover. Subsequent books in the series only identified themselves with their number on the copyright page.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.