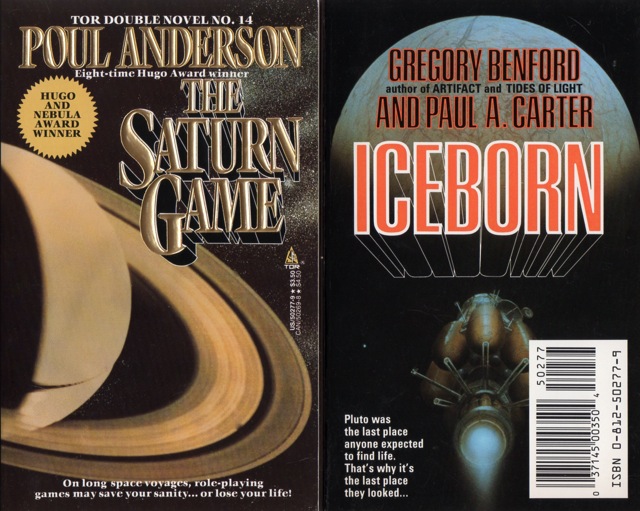

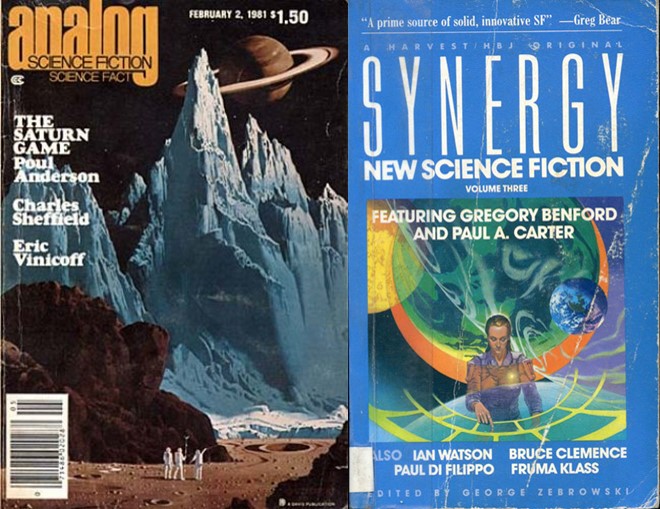

Tor Double #14: Poul Anderson’s The Saturn Game and Gregory Benford and Paul A. Carter’s Iceborn

Cover for Iceborn by Marx Maxwell

The Saturn Game was originally published in Analog in February, 1981. It was nominated for the Hugo Award and the Nebula Award, winning the latter. The Saturn Game is the second of three Anderson stories to be published in the Tor Doubles series after No Truce with Kings.

In 1978, Andre Norton published the novel Quag Keep, widely considered to be the first representation of role playing games in fiction. Norton’s story had a role player fall into Gary Gygax’s World of Greyhawk and live out the sort of adventures that occur in role playing games. By 1981, role playing had become more broadly established, although still niche, especially when compared to today’s popularity. In 1981, Larry Niven and Steven Barnes published Dream Park, in which an amusement park ran what were essentially Live Action Role Playing Games. In the same year, Poul Anderson published The Saturn Game, in which a fantasy role playing game was used in a variety ways on a mission to Saturn.

The Saturn Game begins in the middle of a role-playing session as Anderson’s characters are killing time during the long journey to Saturn. In this sequence, Anderson introduces the reader to the characters, both who they are and who they portray in the game. One of the intriguing things about the importance of the game to the characters is that they are living an adventure: the flight to Saturn, but still feel the need to escape into their world of adventure, although not all of the characters play the game.

Outside the game, the characters take care of business and show they have an understanding of the limits of the game they are playing. Although Jean Broberg and Colin Scobie’s characters are involved in the game, in real life, they are merely friends, Broberg married to another member of the crew and not looking to recreate her character’s relationship in real life. During this exploration, the world of their role-playing game makes a reappearance, initially providing names for the features the group finds on the moon.

Eventually, four of the crew go to explore Saturn’s moon Iapetus, a popular location in science fiction because of its two-toned appearance. While Broberg, Scobie, and Luis Garcilaso, all active participants in the role playing game explore, Mark Danzig remains on their ship, ready to help as needed, but also annoyed by the away team’s constant references to the game he neither plays or has interest in. When their journey becomes difficult, whether it is facing a steep canyon wall or an unexpected discovery, the three crew members refer back to the fantasy game to help them understand what they need to do and work their way through to a resolution, reinforcing the concept of using games to solve problems and not just a means of escapism or entertaining.

The importance of the game, and particularly imagination, is reinforced by the epigraphs Anderson opens each of his chapters with. “Quoting” from the fictional Francis Minamoto’s Death Under Saturn: A Disenting View, these quotes offer a postmortem for the crew’s actions and provide a context as to the role their fantasy game and world may have had in the ultimate outcome of the exploration party.

Stripped of the aspect of the role-playing game, the story is nothing special, relating the actions of a small group of humans exploring an inhospitable moon of Saturn and eventually needing rescue. That part of the story could easily have been written by Murray Leinster or any of a number of other authors decades before Anderson wrote the novella. Anderson’s early interest in the Society for Creative Anachronism and, apparently, role playing games, would seem to make him the person author to lay a veneer of gaming over what could have been a pulp story.

While the introduction of the game and the exploration of its role in human achievement is what sets the story apart, the two sides of the story are not fully integrated. Despite only having four main characters, there is little to differentiate them aside from broad strokes, not helped by the fact that three of them have alter egos who are references in their discussions and in the narrative.

Furthermore, stories of exploration should offer magnificent and strange places to be discovered. The overlay of the game’s mythical venues and the real places on Iapetus make the real places the characters are discovering seem mundane without the magical and legendary elements that adhere to the imaginary places they are compared to.

The Saturn Game offers much more promise than it lives up to. It may be that Anderson didn’t give the story the space it truly needed in order to fully flesh out the characters, the world, and the use of gaming to draw everything together. As it stands, it feels like an ambitious pulp story that doesn’t quite achieve what the author set out to do.

Synergy 3 cover by Alan Okamoto

Iceborn is the first semi-original story to be published in the series and is the first of two collaborations to appear in the Tor Doubles series. An alternate version of Iceborn had previously been published under the title “Proserpina’s Daughter” in George Zebrowski’s Synergy 3 ten months before this Tor Double was published.

Paul A. Carter came up with the initial idea, which Greg Benford helped flesh out. Iceborn tells a first contact story in which a mission to Pluto discovers, much to the crew’s surprise, that Pluto has a living eco-system, apparently the only one in the solar system outside of Earth. Benford and Carter tell their story from different points of view. The first is The Zand, one of Pluto’s native creatures. In its first chapter appearance, it is clear the creature has sentience, although not how much of its behavior is driven by its sentience and how much is instinctive. The second point of view is Shanna West, the only member of the four-person mission to have survived cryosleep. Despite her comrade’s deaths, Shanna is determined to make the mission a success, whatever that means. The final point of view is the Pluto Project’s administrator, Benjamin Rabi, who is stationed on Moonbase One. Viewing Shanna as a surrogate daughter, he works to protect her as best he can from the political machinations caused by her revelations.

The format allows Benford and Carter to tell three different stories. The Zand slowly reveal their nature through their segments, answering the question about how instinctive and how sentient they are, although Shanna’s discoveries also illuminate much about their culture that the Zand are unaware of. Shanna’s story provides the first contact excitement as she learns about Pluto’s fauna. Finally, the story surrounding Rabi shows the world’s reaction to Shanna’s incredible claims, offering the reader context that would have been missing had the authors focused solely on Shanna’s story. Rabi’s conversations with mission doctor Hilge Jensen also reveals information about Shanna, just as Shanna’s discoveries offer information about the Zand.

In order to keep the story streamlined, however, Shanna needs to rely on equipment with near magical properties in order to communicate with the Zand and learn about their way of life. Set against the scientific explanations for life on Pluto and the realistic reactions to the news back on Earth, the super-translator feels out of place, even as it provides Shanna with the information she needs in a timely fashion.

Unfortunately, Iceborn demonstrates some of the issues with writing near future science fiction. Set in the 2040s, a little more than fifty years in the future, Benford and Carter postulate a world in which the United States and Soviet Union are still in a cold war that extends into space. Many of their speculations about Pluto have, of course, been supplanted by the discoveries of New Horizons, which flew by Pluto 10 years ago the week this review is being published. However, the story still works and the reader can mentally make adjustments as necessary to avoid the novella feeling dated.

Overall, Iceborn does an excellent job of combining the feel of pulp science fiction stories that imagined places in our solar system before we knew much about them with a veneer of scientific accuracy. Carter, an historian who began publishing science fiction in 1946, may be responsible for the nostalgic feel of the story’s action while Benford’s scientific understanding helped raise it above the 1940s style of science fiction to give it a more modern feel.

Shanna exemplifies the earlier form of science fiction as the loner who can seemingly accomplish anything she needs to, putting aside the death of her comrades with little emotion, only knowing that she must complete her mission to make sure their sacrifice wasn’t in vain. Rabi represents the more modern, realistic science fiction, dealing with the harsh realities of a Congress which is skittish of “throwing money away in space” especially after three people died on the mission. Their skepticism over Shanna’s incredible claim is understandable and Rabi must navigate that doubt, hampered by the distance between the House of Representatives in Washington and the offices of the Pluto Project on Moonbase One.

The story doesn’t fully overcome its pulp roots, with Shanna’s story firmly rooted in earlier forms of science fiction and Rabi eventually offering a simplistic solution to the problems the Pluto Project at Moonbase One faces. The story needs to end where it does in order to provide a happy ending, but the complications that are set up by that ending are obvious, even if they don’t detract from the story.

The cover photo for The Saturn Game was provided by NASA. The cover for Iceborn was painted by Mark Maxwell.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

Steven H Silver is a twenty-one-time Hugo Award nominee and was the publisher of the Hugo-nominated fanzine Argentus as well as the editor and publisher of ISFiC Press for eight years. He has also edited books for DAW, NESFA Press, and ZNB. His most recent anthology is Alternate Peace and his novel After Hastings was published in 2020. Steven has chaired the first Midwest Construction, Windycon three times, and the SFWA Nebula Conference numerous times. He was programming chair for Chicon 2000 and Vice Chair of Chicon 7.

When did Arthur C. Clarke publish The City and the Stars? It seems to me that it opened with something rather like a roleplaying game, with the protagonist and several friends exploring a virtual environment and having simulated adventures. Admittedly they were doing so as themselves, not as invented characters, but I’m not sure that’s disqualifying; Villains and Vigilantes, one of the first two superhero games, had players play themselves-with-superpowers as their initial characters. But a case might be made that Clarke anticipated the trope before there were real rpgs to base it on.

City and the Stars does open up with a very RPG-like sequence (referred to as a saga). It was originally published in 1956. Against the Fall of Night (1948), which was an earlier version of the story, does not have that opening.

That’s consistent with my vaguer memories. Thanks!

Clifford Simak had a story in the early 1950s (“Shadow Play”, F&SF Nov. 1953) that had a situation similar to Anderson’s “The Saturn Game”. The vehicle was described as the Play rather than a game, but the players (members of an interstellar expedition) created characters that they identified with who interacted with each other, much like player-characters in an RPG.

I remember liking the Simak story better than the Anderson one, but I guess I haven’t read either on for a long time.