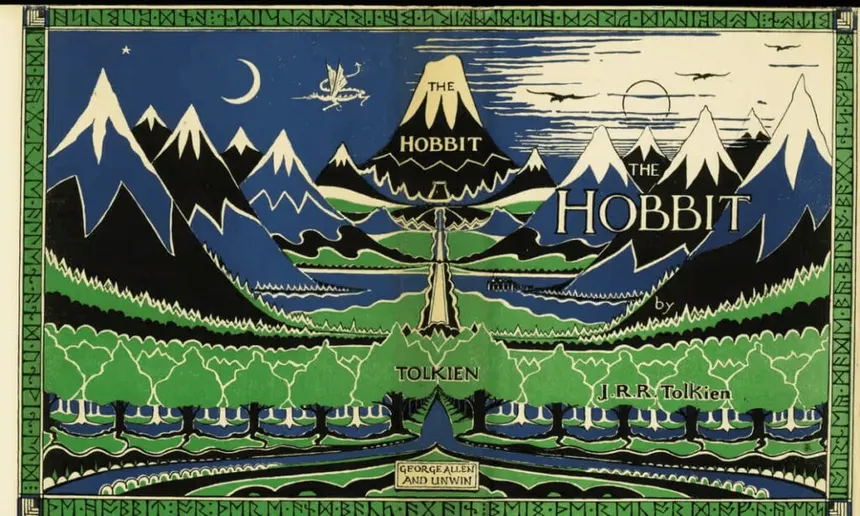

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part Five: From the Beginning — The Hobbit by JRR Tolkien

In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.

Chapter 1, An Unexpected Party – The Hobbit

Fifty years ago, when I first read this book, I didn’t imagine I’d still be reading it so many years later. Heck, I doubt I could have even imagined being as old as I am now. But I do reread it every few years. When I revisit The Hobbit, my journey is bathed in nostalgia as much as with the simple enjoyment caused by reading a charming book that I happen to know inside out, from the opening line above on through to the very end.

In my initial article on half a century of reading Tolkien back in January, I described my dad trying to get our first color tv in time to watch the Rankin & Bass The Hobbit. Remembering that again last week left me thinking more of my dad, now gone nearly 24 years, than the book. He was ten years younger than I am now when the movie first aired, which makes me feel incredibly old at the moment. For such a conservative man, he was excited to see it — admittedly, in a restrained way. I think we liked it well enough, but leaving out Beorn irked us both. Beyond Tolkien’s books, our fantasy tastes rarely coincided (I’ve got a shelf full of David Eddings books he bought, if anyone’s interested), but with The Hobbit and LOTR, we were in complete agreement.

What’s there to say about The Hobbit here on Black Gate? Nothing, really. I imagine most visitors here have read it, many more than once, and have their own ideas on it. It’s one of the most widely read books in the world. Instead, I’m going to discuss some adaptations of the book. But first, a summary.

Hobbits are Tolkien’s slightly comical take on the staid British country folk. Their homeland is so British in nature, it’s even called the Shire. They prefer comfort and predictability and tend toward stoutness. Bilbo Baggins, the only son of wealthy parents has settled into a very predictable and very comfortable middle-age. When Gandalf, a wizard known fondly for magnificent fireworks and less fondly for occasionally leading young hobbits off on some adventure, appears at his doorstep, Bilbo’s life takes a drastic turn. The wizard has come to bring Bilbo on an adventure. Despite the hobbit’s denial of any interest in such an undertaking, Gandalf leaves a mark on his door so a throng of dwarves can find their way their the next day.

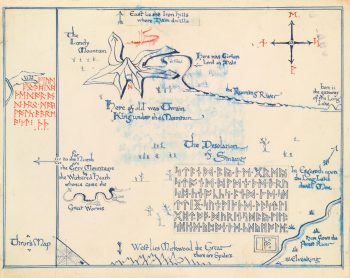

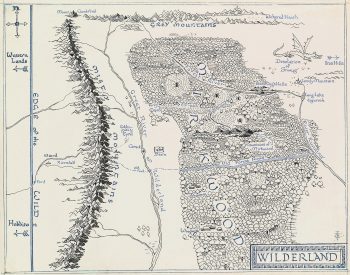

The dwarves, led by Thorin Oakenshield, are survivors of the Lonely Mountain. Once a mighty and wealthy dwarven stronghold, one hundred and seventy one years earlier, it was sacked by the great dragon Smaug and its citizens killed or driven out. Save Thorin and one other, the dwarves are miners and smiths, not fighters. Still, the band is determined to reclaim their mountain and their treasure, despite having neither a plan nor the means to remove the dragon.

Succumbing to a repressed ancestral taste for adventure, Bilbo joins the dwarven company on its quest. Soon, Bilbo finds himself on the wrong side of hungry trolls, angry goblins, and, perhaps worst of all, Gollum.

Deep down here by the dark water lived old Gollum, a small slimy creature. I don’t know where he came from, nor who or what he was. He was Gollum—as dark as darkness, except for two big round pale eyes in his thin face. He had a little boat, and he rowed about quite quietly on the lake; for lake it was, wide and deep and deadly cold. He paddled it with large feet dangling over the side, but never a ripple did he make. Not he. He was looking out of his pale lamp-like eyes for blind fish, which he grabbed with his long fingers as quick as thinking. He liked meat too. Goblin he thought good, when he could get it; but he took care they never found him out. He just throttled them from behind, if they ever came down alone anywhere near the edge of the water, while he was prowling about. They very seldom did, for they had a feeling that something unpleasant was lurking down there, down at the very roots of the mountain. They had come on the lake, when they were tunnelling down long ago, and they found they could go no further; so there their road ended in that direction, and there was no reason to go that way—unless the Great Goblin sent them. Sometimes he took a fancy for fish from the lake, and sometimes neither goblin nor fish came back.

Just prior to his encounter with Gollum, Bilbo finds a plain golden ring, a Ring that will come to prove of vital importance in later years. After discovering it turns its wearer invisible, Bilbo uses it to his advantage to escape from the goblins, and to save the dwarves on several occasions, once from giant spiders and once from elven prison cells. Eventually, he even uses it to allow himself to engage in some dangerous banter with the dragon.

“Well, thief! I smell you and I feel your air. I hear your breath. Come along! Help yourself again, there is plenty and to spare!”

But Bilbo was not quite so unlearned in dragon-lore as all that, and if Smaug hoped to get him to come nearer so easily he was disappointed. “No thank you, O Smaug the Tremendous!” he replied.

“I did not come for presents. I only wished to have a look at you and see if you were truly as great as tales say. I did not believe them.”

“Do you now?” said the dragon somewhat flattered, even though he did not believe a word of it.

“Truly songs and tales fall utterly short of the reality, O Smaug the Chiefest and Greatest of Calamities,” replied Bilbo.

“You have nice manners for a thief and a liar,” said the dragon. “You seem familiar with my name, but I don’t seem to remember smelling you before. Who are you and where do you come from, may I ask?”

“You may indeed! I come from under the hill, and under the hills and over the hills my paths led. And through the air. I am he that walks unseen.”

“So I can well believe,” said Smaug, “but that is hardly your usual name.”

“I am the clue-finder, the web-cutter, the stinging fly. I was chosen for the lucky number.”

“Lovely titles!” sneered the dragon. “But lucky numbers don’t always come off.”

“I am he that buries his friends alive and drowns them and draws them alive again from the water. I came from the end of a bag, but no bag went over me.”

“These don’t sound so creditable,” scoffed Smaug. “I am the friend of bears and the guest of eagles. I am Ringwinner and Luckwearer; and I am Barrel-rider,” went on Bilbo beginning to be pleased with his riddling.

“That’s better!” said Smaug. “But don’t let your imagination run away with you!”

By hands other than their own, the dwarves find themselves rid of the dragon. This leaves them in control of the mountain and the treasure. Part of the treasure, though, is sought, not unreasonably, by the dragon’s slayer, among others. Dwarves, being dwarves — “dwarves are not heroes, but calculating folk with a great idea of the value of money” — have no intention of giving up one farthing of their hoard, and soon the stage is set for a great battle. Bilbo makes it home, but only after having to commit an act of great moral bravery. The hobbit who returns home is not the same as the one who left, which of course, will turn out to be of the greatest importance for Middle-earth in the years to come.

The first and best adaptation I’m familiar with is the audio version performed by Nicol Williamson for Argo Records in 1974. Lasting nearly four hours, it has the room to tell most of the story. I remember my mother bringing it home from the library and realizing how long and complete it was. I listened to all of it on a Saturday and loved every minute of it.

Williamson himself did many of the edits, removing the most of the ‘he saids.’ He used various regional UK accents to differentiate the various characters. Williamson was one of the great stage actors of the last century, possessed of an absolutely magnificent and captivating voice. I haven’t listened to all of Andy Serkis’ unabridged presentation of the book, but as good as what I’ve heard is, Williamson’s is still the winner. Here’s Part Two of Williamson’s version, starting with Bilbo’s encounter with a wonderfully ghastly sounding Gollum.

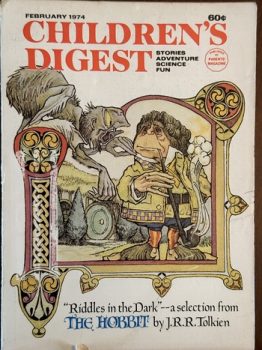

The video clip above of Bilbo and Smaug in the summary is from the second adaptation, the 1977 Rankin and Bass animated The Hobbit. The character designs were by Lester Abrams who had illustrated the Bilbo-Gollum confrontation for Children’s Digest. Arthur Rankin had seent he illustrations and liked them enough to engage Abrams for the movie. The animation was done by the Japanese company Topcraft (which would later go on to do Miyazaki’s first movie, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and become part of the foundation of Studio Ghibli).

The video clip above of Bilbo and Smaug in the summary is from the second adaptation, the 1977 Rankin and Bass animated The Hobbit. The character designs were by Lester Abrams who had illustrated the Bilbo-Gollum confrontation for Children’s Digest. Arthur Rankin had seent he illustrations and liked them enough to engage Abrams for the movie. The animation was done by the Japanese company Topcraft (which would later go on to do Miyazaki’s first movie, Nausicaä of the Valley of the Wind, and become part of the foundation of Studio Ghibli).

I love the movie, despite its too-rapid pace, the elimination of Beorn, and overall simplification. The painted scenery and backgrounds are wonderful, presenting Middle-earth in warm, muted colors. It looks at once realistic and fantastic. The voice acting, if not of Williamson’s caliber, is first-class, with Orson Bean as Bilbo, John Huston as Gandalf, Hans Conreid as Thorin, and, most wonderfully, Brother Theodore as Gollum.

It’s far from perfect, but it succeeds better than anything else at conveying a sense of real wonder with each new encounter Bilbo has with the increasingly strange and dangerous denizens of the Wilderlands east of the Shire. Rankin had declared that there would be nothing in the movie that wasn’t in the book, and he proved largely true to his word. It also makes good use of Tolkien’s songs. I admit to not loving Tolkien’s songs and poetry in The Lord of the Rings, but in The Hobbit, he provides some solid children’s poetry and it carries over well in the film. That it remains a children’s film and not some tarted up action movie is its greatest strength. Bilbo is a likeable and brave, and the scary bits are just scary enough for young viewers. At 78 minutes, it’s also the perfect length to get exposed to Middle-earth and JRR Tolkien.

I haven’t much to say about Peter Jackson’s three, interminable, cacophonous movies save “I give up!” I feel like I watched them for penance for any and all sins I’ve ever committed and will yet commit. Martin Freeman is fine enough, if far too thin, as Bilbo, but everything else is awful. Instead of the episodic charm of JRR Tolkien’s actual book, Jackson delivered three movies totaling nearly eight hours of sodden, CGI-infested stuff, packed full of things JRR Tolkien could never have conceived of.

Like with his LOTR trilogy, the films diverge from their sources the further they move along. While the first, An Unexpected Journey (2012), largely follows the form and shape of the book, the second, The Desolation of Smaug (2013), adds an unbelievably poor romantic entanglement and hints of municipal corruption in Lake Town. The dwarves Rube Goldberg plan to encase Smaug in molten gold had me wishing I had more hair to pull out of my head. By the third chapter, The Battle of the Five Armies (2014), all bets are apparently off. Even though I hate Jackson’s desire to turn the the titular battle into a gigantic spectacle, I understand it. The shenanigans of the the Master of Lake Town, however, are awful and nothing anybody who’s at all interested in the fate of Bilbo and the dwarves will be at all interested watching.

Oh, and I haven’t mentioned the terrible-looking and slog that is Gandalf and the White Council’s battle with the Necromancer, aka Sauron. No more than a plot device to extract Gandalf from the story, Jackson turned it into a great, big thing. It was fun to imagine just what happened while reading the book, but on the screen, it’s just one more great big distraction from what should be the only focus — Bilbo and the dwarves. And bird crap-covered Radagast and his bunny-draw sledge is stupid.

The great thing about the Jackson’s movies is that you don’t have to watch them if you want some sort of theatrical presentation of The Hobbit. Just go listen to Williamson (or Serkis, if you prefer) or watch the Rankin and Bass. Both are clearly works of love and respect for JRR Tolkien’s actual book and almost as much fun as reading the book itself.

Next month, I think it’s a time for something special; a visit to the Harvard Lampoon’s tremendously funny and offensive parody (and excellent pastiche) of Lord of the Rings, the Harvard Lampoon’s 1969 Bored of the Rings.

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part One

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part Two – The Fellowship of the Ring by JRR Tolkien

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part Three — The Two Towers by JRR Tolkien

Half a Century of Reading Tolkien: Part Four — The Return of the King by JRR Tolkien

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Sunday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him

I agree with the note of appreciation for the Rankin-Bass adaptation of The Hobbit. (I am a fan of their Return of the King, as well.). Brother Theodore as Gollum was my first exposure to his wonderful, off-beat comic insanity. And it all came at the right time as I had just read LotR.

Actually, I will confess to being too old at the time to read The Hobbit, being an overly mature 17 year old. One winning point for LotR was having the prologue “Concerning Hobbits” available to free me from the task of reading some kiddie lit. Later, I was old enough to read The Hobbit and did enjoy it.

And while I sigh a lot over the Peter Jackson adaptation of The Hobbit, at least Radagast was portrayed by Sylvester McCoy, otherwise known as Doctor #7, the last of the original run Doctor Who Time Lords.

Jackson’s biggest crime was turning a children’s book into an overstuffed, (bad) action movie. Anyone who gives Sylvester McCoy work should be alright by me, but not here

We got our first color TV in the mid seventies. Prior to that the whole family would go over to my nana’s house to watch specials like “A Charlie Brown Christmas” on her color set which seemed like such a luxury. I thought mt family was the last holdout in the country with a B&W TV but I guess not.

I read “The Hobbit” in high school and thought it was thoroughly charming and one of those rarest of perfect books I wouldn’t change a word of. It encapsulates everything wonderful about reading a well-written children’s book, at once rich with imaginative detail while graced by a clean purity of design and execution.

I agree with everything you wrote about the Rankin/Bass adaptation. Hiring Abrams was a brilliant move as the overall design, especially the characters and backgrounds, are marvelous and remain the best evocation of Middle Earth yet in print or film and this remains the only depiction of Gollum that captures Tolkien’s original depiction in the book. Similarly the voice cast is largely fine and while I wouldn’t have cast Bean he acquits himself adequately. More than anything, this was clearly a handcrafted labor of love, something we’ll never see again in the era of corporate owned IP and AI slop.

There was a nice vinyl box set of the soundtrack in the late seventies with a beautiful illustrated booklet of images from the film which I owned but stupidly got rid of years ago and an even more lavishly illustrated coffee table book that is now obscenely expensive.

I never listened to the Williamson audio adaptation but I distinctly remember being in assorted record stores, holding the hefty vinyl box set in my hands and being tempted. Perhaps one of these days.

Thanks for the memories.

My folks were cheap Depression babies (especially my dad), so they needed a prompt like The Hobbit to finally bit the bullet. I ended up listening to about a third of the Williamson album (it’s on Spotify and Youtube) and it’s very, very good.

I’m still waiting for Warner Brothers (or whomever) to get off their butts and do a PROPER HD remaster and rerelease of the Hobbit cartoon. And the two LotR animated movies, as long as they’re at it.

The Rankin and Bass Hobbit led me to the book and from there many years of reading fantasy (and continuing to do so). Perhaps because it was my first visual contact with hobbits, it is how I imagine them. I have never warmed up to other representations (Sweet’s or the brothers Hildebrandt) although I enjoy Alan Lee’s overall LOTR illustrations and of course, Tolkien’s.

I like the Hildebrandt’s, despite their stiffness, largely out of nostalgia and their side-of-a-van worthiness. I used to be much more happy with Alan Lee’s work, but it’s come to seem too drab over time. Sweet is Sweet and he doesn’t work for Tolkien. The Rankin Bass designs, though, are still probably my favorites overall.

While the Jackson adaptations are quite poor, I have zero affection for the Rankin-Bass effort either. The Hobbit remains ripe for a quality film experience. I suspect it will be difficult to find: directions are wont to either be too precious with the material or too eager to “improve” it with changes. It’s a shame: this is the book that should be relatively easy to adapt and require much less trimming to put it into a reasonable run time.

I did think Jackson cast his films pretty well, but otherwise it simply didn’t work very well. I was excited about the idea of seeing what Gandalf and the White Council were up to off screen, but the execution left much to be desired. And it’s always bad when Jackson decides a character is comedy relief, because he locks them into that role with no real escape.

The Rankin-Bass version is too cutesy for me and lacks depth, which the book still has, despite being more of a children’s story and much more densely plotted and light-hearted overall.

I’d love to see something better than Rankin and Bass that gets more of the melancholia and darkness that emerges in the latter part of the book. As for Jackson’s abominations, Freeman’s decent enough, if too thin, but I dislike Thorin, and much of the rest of the cast.

“ The great thing about the Jackson’s movies is that you don’t have to watch them”.

Exactly. I walked out of the first one and never saw the others.

I absolutely adore the Rankin and Boss Hobbit. I agree completely that it “it succeeds better than anything else at conveying a sense of real wonder with each new encounter Bilbo has with the increasingly strange and dangerous denizens of the Wilderland.”

I watched it on TV in 1977, and it was a revelation. Watching the brief clip you shared above brought back all the wonder and magic of seeing it on screen at the age of 13.

Something you didn’t mention was the soundtrack by Glenn Yarbrough. To me, it’s far and away the best musical adaptation of Tolkien’s songs, especially track #7 (Gandalf’s Reflection), #11 (Funny Little Things), and #13 (Misty Mountains Cold).

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TngincGfzfc&list=PL545948224B999E8A&index=10

Even if it does sometimes sound like he’s singing through a box fan. But all of those songs have lived rent-free in my head for the past 48 years now.

I didn’t and should have. I can live without most of the songs/poems in LotR, but The Hobbit’s verses are so much fun and the film really does them justice