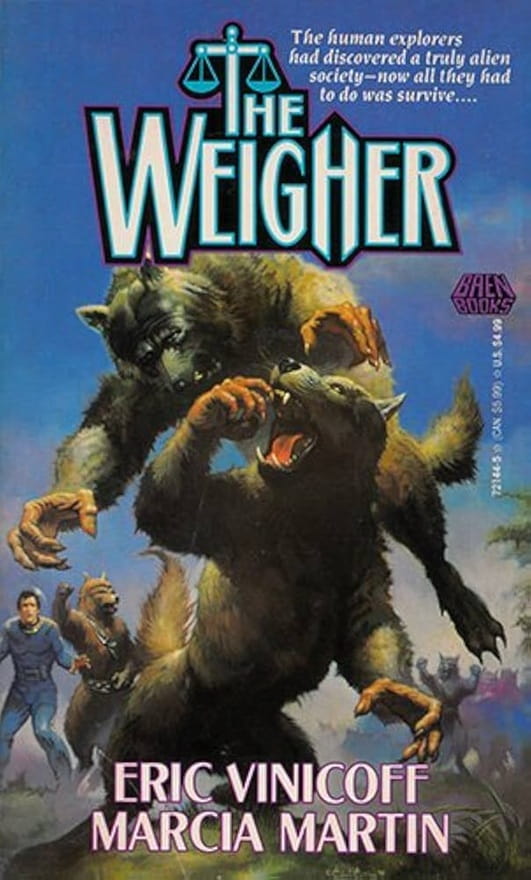

A Kind of Thought Experiment: The Weigher by Eric Vinicoff and Marcia Martin

|

|

The Weigher (Baen Books, November 1992). Cover by C. W. Kelly

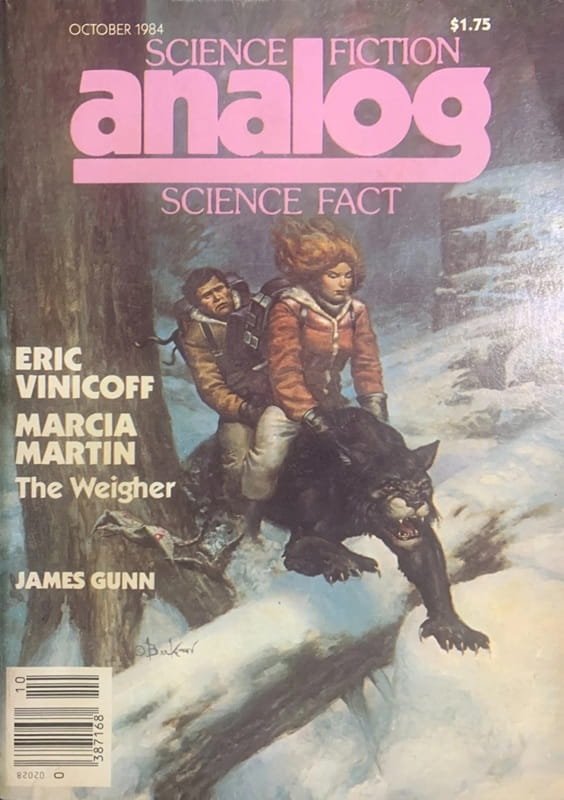

First contact stories are one of science fiction’s major subgenres, an important branch of stories about aliens, going back at least to H. G. Wells’s The First Men in the Moon. The usual point of view is a human one; after all, humans are familiar and nonhumans are not, and that way the reader can share the protagonist’s discovery of a new species and culture. But every so often, a writer tells the story from the nonhuman point of view. The Weigher, published first in Analog in 1984 and then expanded into a novel in 1992, is one of these ventures.

What adds interest to this is that the culture of the aliens is worked out in some detail, and is different from our own culture in major ways, and probably from a lot of human cultures. Some of these differences reflect different biology and psychology; others probably don’t, such as the version of money in use.

[Click the images for versions with greater weight.]

|

|

Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact , October 1984, containing

the novella version of The Weigher. Cover by Doug Beekman

These particular aliens are large, somewhat catlike obligate carnivores. They seem to be larger than human beings and more formidable in a fight; they also have keener senses, in particular smell (they can judge each other’s mood by odor) and night vision. They may be better at long distance mobility than felids generally are, but their ability to sustain high speed only lasts for a fairly short time; the protagonist and narrator, Slasher, remarks several times on being close to exhaustion. Perhaps just as importantly, they’re intensely individualistic, and ready to fight for their rights — often to the death.

The title of the novel refers to Slasher’s profession, which amounts to providing as much legality as such a race can support — not as a police officer (law enforcement is by self-help) but as a kind of judge. It’s as a judge that she gets involved in the plot: She’s called in when a strange creature is killed while looking at a healer’s medical equipment, and a savant wants to buy the remains for dissection. They disagree on a fair price, and want Slasher to come up with one.

This is the first of a series of encounters, leading up to Slasher’s forming an alliance with two living creatures, who (unsurprisingly) turn out to call themselves “humans”: Ralphayers and Pamayers. They’re there to study Slasher’s people and culture, there is no one else of their kind to come to their aid, and they need Slasher’s guardianship to keep them alive, not least because some people think of them as demons. Of course, this leads to Slasher’s getting in several different kinds of trouble; in a classic plot structure, each attempt to resolve a problem leads to further complications. This must have been a perfect story for Analog!

Along the way, we learn a lot about Slasher’s world: its family structure and mating customs, its economics, its technology, its legal system, and its diverse cultures and religions. Ralphayers and Pamayers play the role of Watson, asking questions and puzzling over why the world is as it is. They’re able to support themselves by trading useful knowledge for this world’s version of money, twilga. Unfortunately, their knowledge of law proves not to be so useful; taking their advice gets Slasher in deep trouble, which drives a lot of the plot.

An underlying issue in this book is an exploration of how a kind of libertarianism can be compatible with providing any sort of collective goods. It reads like a kind of thought experiment in economic and legal institutions. Some science fiction has dealt with such issues by postulating human cultures that are far more individualistic than real human societies; Vinicoff and Martin instead give us a species for which that individualism is natural.

Its societies are all relatively small-scale (which makes sense) and have simple customs and institutions, so it’s straightforward to see the tradeoffs and incentives at work. That makes the narrative less subtle than it might have been, rather like an Icelandic saga (I’ve seen the comment that the two main activities of saga characters seem to have been fighting each other and suing each other) — of course, Iceland was also a small-scale society.

For all that simplicity, I found The Weigher an interesting story and an interesting piece of worldbuilding. I’m not always sure that the way of life it portrays is workable; in particular, I’m not sure its childrearing practices really are compatible with having any kind of sustainable culture. But it provides a setting for the classic sort of social science fiction.

And it’s interesting to see its portrayal of an entire society of what look like Conanesque barbarians, male and female — one that supports an adventure story, as Slasher, her human friends, and her adopted child/servant Runt wander about the world looking for a solution to Slasher’s problems. The one that they eventually find has the virtue of being both unexpected and logical, which is a good way to resolve a plot — and points toward a less barbaric future.

William H. Stoddard is a professional copy editor specializing in scholarly and scientific publications. As a secondary career, he has written more than two dozen books for Steve Jackson Games, starting in 2000 with GURPS Steampunk. He lives in Lawrence, Kansas with his wife, their cat (a ginger tabby), and a hundred shelf feet of books, including large amounts of science fiction, fantasy, and graphic novels.