A Boy Scout’s Handbook: The Mysterious Island

One of the more popular time-wasting activities these days is the “desert island” game, where people compile lists of books, albums, and movies that they could in no instance dispense with, works that they would take with them if they had to be exiled for life on a desert island. In this exercise, esthetic or just plain entertainment qualities reign supreme, but if we were talking about surviving on an actual island, uninhabited, unsettled, untamed, practical considerations would come to the fore; I don’t think The Sopranos would be of much use when it came to building a shelter or planting a crop, and as for Survivor, is there anything more contrived than a “reality” show? (My actual TV choice, Green Acres, would be marginally better but still likely inadequate.)

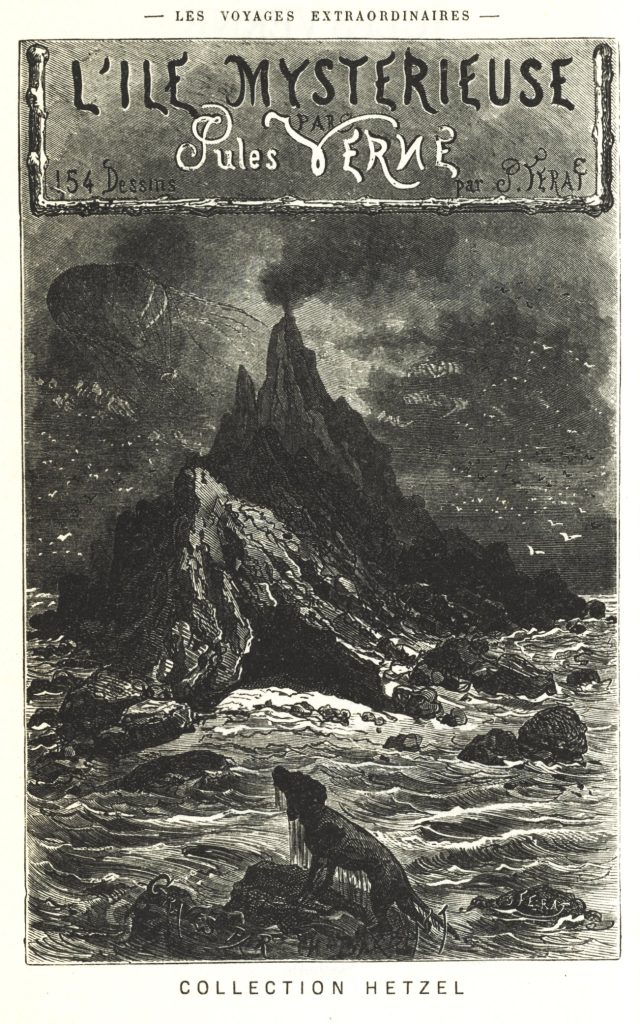

As for books, I recently read something that would definitely make the real desert island cut — Jules Verne’s The Mysterious Island. It’s a veritable Swiss army knife of a book, full of useful hints and practical advice, whether you want to lower the level of a lake, make nitroglycerin, cook a capybara or construct a seaworthy, two-hundred-ton ship from scratch. It’s a book no Boy Scout should leave home without.

Published serially in 1874 and 1875, The Mysterious Island is a classic Robinsonade, a genre named after Daniel Defoe’s 1719 novel Robinson Crusoe. Robinsonades are books in which people are shipwrecked on isolated islands or stranded in other remote areas and are thrown back almost entirely on their own resources. Inherently dramatic, such stories have proven enduringly popular, with examples such as Johann Wyss’s The Swiss Family Robinson, R.M. Ballantyne’s The Coral Island, and William Golding’s Lord of the Flies rarely if ever falling out of print.

Verne’s novel is squarely in this tradition and is as full of excitement and adventure as any thrill-seeker could wish, though fans of the 1961 Cy Endfield-Ray Harryhausen film (of whom I definitely am one) will be disappointed to discover that there are no giant crabs, birds, bees or cephalopods in the book. The disappointment will be brief, however, as there are many other dangers and challenges in the six hundred-plus pages of Verne’s yarn, more than could comfortably fit into three movies.

The disappointment may return, though, when readers realize that, again unlike the movie, there are no gorgeous and scantily-clad female castaways in the novel; from start to finish, the island remains a completely — indeed, enthusiastically — male society. (Women aren’t even mentioned until the last few pages, and when, as happens several times, a red-blooded male delightedly exclaims that their little colony has everything that it will ever need, there is no trace of irony detectable coming from either the character or from Verne himself. Readers, on the other hand, can’t help but shake their heads; well before the end, my neck had gotten pretty sore.)

The story begins in Richmond, Virginia, in the waning days of the American Civil War, when five Union prisoners, not knowing that the war will be over in a month or two, escape from their captivity in an observation balloon. Caught in a storm of historic proportions, the balloon is carried all the way across North America and most of the way across the Pacific Ocean, finally running out of gas — literally — and depositing the escapees on an uncharted, uninhabited volcanic island south of the Equator, located about 1,500 miles west of New Zealand and just about as far east of the coast of South America.

Our heroes (I was gratified to find that Verne’s book actually has heroes) are Americans all: Cyrus Smith, the undisputed leader of the group, an engineer in the Union army who seemingly knows just about everything about just about everything, Gideon Spillet, a newspaper reporter who knows the little that Smith doesn’t, Pencroff, a sailor of inexhaustible energy and excitable temperament, his adopted adolescent son Harbert, a precocious youth with an extensive knowledge of botany and zoology, and Neb (short for Nebuchadnezzar), a former slave freed by Smith whose loyalty to his benefactor is such that when he found out Smith had been captured by the Confederates, he traveled from the free states to share in his captivity, which apparently flummoxed the Southerners so much that that they allowed him to join Smith in prison instead of reenslaving him. The five men are also accompanied by Smith’s dog, Top. You need know nothing more to understand why the South lost the war.

Once dropped on their island, the castaways lose no time in shaping it according to their needs. This task is made easier by the extraordinary (wildly unlikely is perhaps a more accurate description) diversity of the island’s flora, fauna, and mineralogical resources. It’s not long before they have Lincoln Island (so they christen it) well on the way to being ready for statehood. (They of course immediately claim the island for the United States.) No time is wasted reclining in palm tree-shaded hammocks and sipping drinks out of coconut shells while being cooled by ocean breezes — this is not that kind of island.

Every day is another project. They use the nitro that Smith concocts to lower the level of a lake so that they can have access to a cave system in a cliffside, which they then occupy and modify to make it their dwelling, dubbing it Granite House. They construct a kiln and use it to make pottery and bricks. They plant crops and build a windmill for milling grain. They divert watercourses and build drawbridges to keep predators away from the livestock that they have domesticated. They build a telegraph to establish communications between Granite House and an isolated sheepfold that they establish several miles away. They build rafts for transporting raw materials on the island’s rivers and a larger boat (which they name the Bonadventure — Pencroff’s first name, which understandably no one ever uses) for circumnavigating their domain. By the end of the story, they are well on the way to making their home a miniature Boston or Philadelphia.

All of these accomplishments are made possible by Smith’s good old American know-how and the cheerful labor of the other colonists (as they quickly come to think of themselves). Smith and his friends are intelligent men, experienced and resourceful, but Verne doesn’t present them as supermen; he implies that they are pretty much your average Yankees, and that any reasonably motivated group ought to be able to do as much as they did.

Along the way there a lot (and I mean a lot) of passages like this:

Once the fire had completely reduced the pile of pyrites, the resulting matter, consisting of iron sulfate, aluminum sulfate, silica, charcoal residue, and ashes, was shoveled into a water-filled basin. They stirred this mixture, let it rest, then poured it off into another vessel, obtaining a light-colored liquid that held the iron sulfate and aluminum sulfate in suspension; the other substances had been left behind as solids, since they were not soluble. Finally, once the liquid had partially evaporated, the crystals of iron sulfate precipitated out, and the mother liquor, that is, the unevaporated liquid containing the aluminum sulfate, was discarded.

This is just one paragraph of the procedure for making nitroglycerin; the whole thing takes up four pages, and making nitro is just one of many, many jobs that our protagonists undertake. Their days are filled with practical projects in chemistry, metallurgy, carpentry, animal husbandry, botany and more. The colonists never seem to get exhausted, but the same can’t always be said for the reader.

It is hard going sometimes, but Verne was clearly enthralled by this kind of thing, and he manages to convey a large measure of that enthusiasm to the reader; you can’t help but feel his fascination with the natural world and its awesome potentialities, and you share in the castaways’ pleasure at seeing their efforts to “tame” and “civilize” the island succeed so well, despite those particular words having gone so far out of fashion. Indeed, in a time when so much fiction is concerned with abstract matters, it’s a positive pleasure to read a book where people are really getting their hands dirty, with something tangible to show for it at the end.

And in addition to lessons in chemistry, mechanics, and hydraulics, Verne fills the book with plenty of straightforward action. Granite House is invaded by a legion of monkeys; the precious crops are threatened by an army of rampaging foxes that have to be fought off with gun, club, and claw (the hero of this battle is Joop, an orangutang captured in the monkey scuffle who is domesticated and becomes one of the gang, more or less, and is the most appealing character in the whole story); after finding a message in a bottle, Pencroff and Spillet take the Bonadventure on a perilous voyage to an island one hundred and thirty miles away to rescue a shipwrecked mariner named Aryton who has descended to savagery (the scenes where the colonists coax the degraded sailor back to humanity are among the best in the book); and most seriously, the colony is menaced by a shipload of ruthless convicts who almost kill Harbert and have to be mercilessly dealt with. And hovering over everything is the enigma that makes the island a mysterious one.

Early on, the group determines that Lincoln Island is and seemingly always has been uninhabited… and yet from the beginning there is a strange presence lurking about the place, a benevolent, helpful presence it is true, but no less puzzling for that. Someone rescued an unconscious Cyrus Smith from drowning when the balloon dropped the group on the shore; someone placed a chest with priceless tools and other supplies just where they would find it; someone put a box of medicine on a table in Granite House when it was the only thing that would save Harbert’s life; someone destroyed the convict’s ship with an underwater mine.

Despite searching every inch of the island, Smith and the others are never able to find their benefactor, and they decide that he will reveal himself only when he wants to… as he finally does with about fifty pages to go. Do I need to wave the spoiler alert flag? Do I need to worry about spilling a one hundred-and fifty-year-old book’s beans? Well, avert your eyes if you can’t handle the truth.

The “genii of the island” as the castaways think of him, is none other than… Captain Nemo! Cyrus Smith had already figured that out, having read “an account of your history that has since been published, under the title Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea.”

The captain summons the group to the Nautilus where he explains that his crew have all died and that he too, is dying. He secretly observed the castaways from the beginning and, admiring their courage and resourcefulness, determined to help them when they needed it. He also tells the castaways something that the characters in Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea never learned: his origin story. Nemo is actually Prince Dakkar of India, burning with hatred for Great Britain, the oppressor of his people. Dakkar was the secret organizer of the Sepoy uprising of 1857, and when the mutiny failed and his wife and children perished in the conflict, he withdrew from corrupt civilization and became Nemo, using his vast learning and scientific brilliance to construct the vessel that would enable him to live in a purer realm.

He gives the men a casket full of jewels that will make them wealthy, tells them that their beloved island will be blown to smithereens soon by the reawakening volcano, and dies, descending to the bottom of the sea in his fabulous submarine, which will be his tomb for all eternity.

The colonists throw themselves into finishing a larger craft that they are working on to take them to safety (the original Bonadventure was destroyed by the convicts), but before they are able to finish it, Lincoln Island is obliterated by the buildup of volcanic forces, leaving only a small outcrop of rock jutting from the sea, from which the men (and Top — Joop was the only casualty, which rather ticked me off) are rescued by a passing ship.

Brothers to the end, they take their fortune in jewels and recreate their community in Iowa, of all places, where they “invited all those they had hoped to bring to Lincoln Island, offering them a life of wholesome labor, which is to say a rich and happy life. They founded a great colony… It was like an island in the middle of a continent.”

The Mysterious Island is my first Jules Verne; I had never read him before, and despite the book’s undeniable flaws, I quite enjoyed my inaugural voyage extraordinaire. (I read the Modern Library edition, translated by Jordan Stump, with over fifty of Jules-Descartes Ferat’s illustrations from the original 1875 edition.)

Allowances have to be made for a book of this vintage, of course; there are few moments when you can forget that it is the product of the nineteenth century, an age that was in many ways about as different from our own as can be imagined.

Certainly no one today would use the words “colonists” and “colony” in the positive, non-pejorative way that Verne uses them, and while Nemo rages about the crimes of British imperialism (Verne apparently hated Great Britain; still smarting over Agincourt, I guess) one can’t help but think about the French empire in Indochina and wonder what Jules had to say about that. The castaways’ eagerness (and assumption of the right) to “claim” the island for their country would cause contemporary eyebrows to lift, but the book probably shows its age most in the character of Neb. Verne doubtless thought himself progressive in including a black castaway at all, but unsurprisingly his treatment of the ex-slave is not free of condescension or worse (Neb never calls Cyrus Smith his “master,” but Verne often does). You can tell that by his lights, Verne is trying hard to treat Neb as an equal member of the group, and while he doesn’t always succeed in this goal, neither does he always fail. Nevertheless, many will still find the depiction of the character offensive.

But the thing that most marks The Mysterious Island as an artifact from someplace far, far away is an attitude and an assumption — every page shines with an optimism and unalloyed faith in reason (and faith in faith, too — the colonists frequently offer up thanks to their Creator) that have become increasingly alien in this decidedly non-Vernian far future that we’ve wound up living in. When was the last time you read a six-hundred-page book without a single cynical word in it?

More than the complete harmony and lack of conflict between the men (there are no personal problems on Lincoln Island — all problems there are mechanical), more than the island being presented as a delightful puzzle to solve or an enormous toy box to open, more even than the total lack of the female sex (that not one of these supposedly grown men sees as a problem or even notices!), it’s this fresh, optimistic view of the world (call it naivete if you will) that marks The Mysterious Island as fundamentally a boy’s book. That doesn’t mean it’s valueless, though, even for non-adolescents.

Verne’s sunny view of the world and of our place in it may not be strictly realistic, but it is undeniably pleasant, and even inspiring and possibly useful. We’re all shipwrecked somewhere, aren’t we, and when you find yourself cold and wet and shivering on the beach, you can curl up and cry and start dying of exposure or starvation… or you can inventory what you’ve got in your pockets, survey the landscape, and get to work. In fiction or in life, it’s not a bad philosophy, and there are worse tools to have in your box than L’Île mystérieuse.

So just ask yourself — WWJVD? (What would Jules Verne do?) The sooner you get that telegraph built the better.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was By the King’s Command: Joan Samson’s The Auctioneer

The Mysterious Island was my first Jules Verne “voyages extraordinaires”, too, though my 8-year-old self would not have noticed much of the dated material in the book, even 50 years ago. I can recommend A Journey to the Center of the Earth for more of his “adventure-filled-with-science” fiction, though the obvious follow-up read would be 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea. What a great reveal that turned out to be: Captain Nemo!

A helpful reminder that I have a WHOLE bunch of Jules Verne that I haven’t read yet.

“ Verne apparently hated Great Britain; still smarting over Agincourt, I guess”

Much more likely Waterloo.