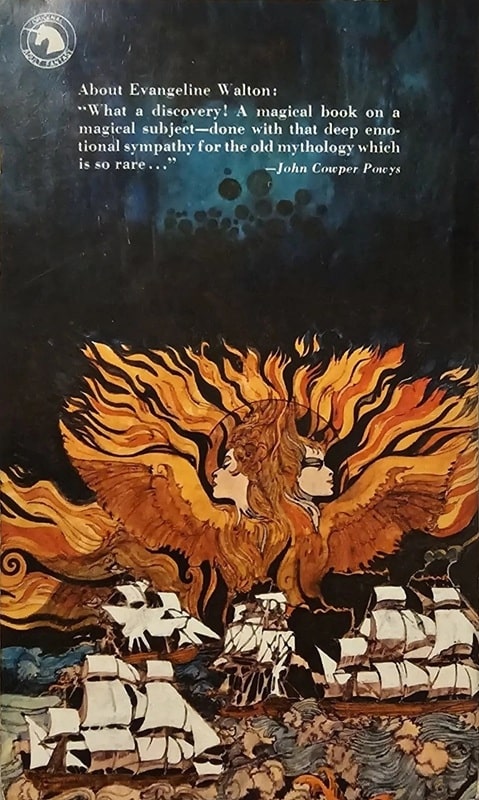

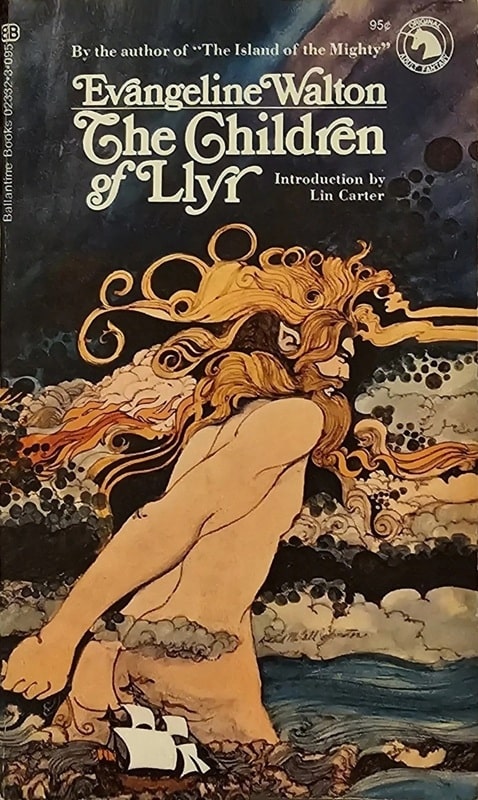

An Original Ballantine Adult Fantasy: The Children of Llyr by Evangeline Walton

|

|

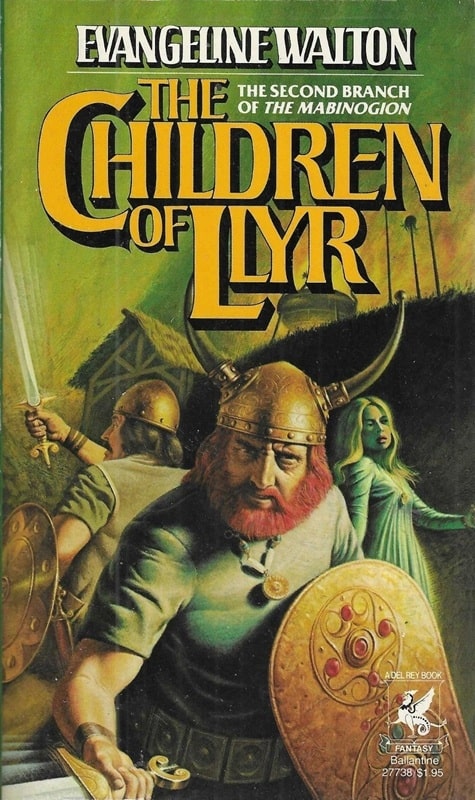

The Children of Llyr (Ballantine Adult Fantasy #33, August 1971). Cover by David Johnston

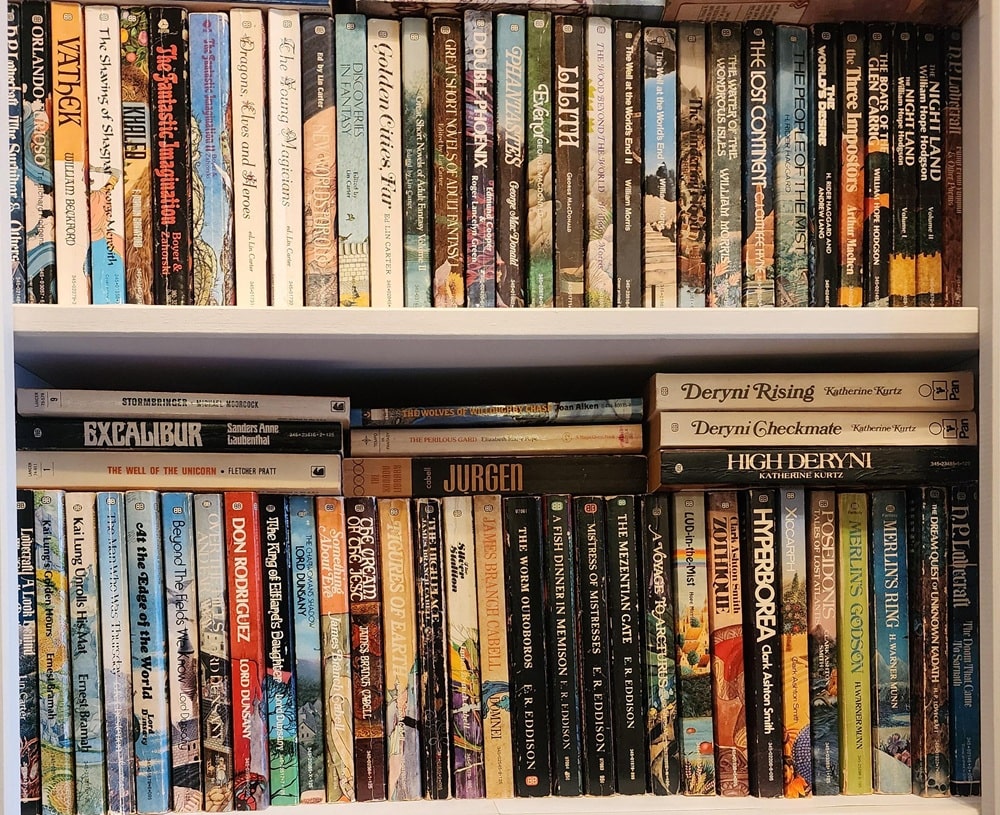

This latest entry in my series of essays about mostly obscure SF and Fantasy from the ’70s and ’80s looks at a novel published in one of the most celebrated publishing series of the early ’70s. This was the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, which ran from 1969 to 1974, under the editorship of Betty Ballantine, with the assistance of “Editorial Consultant” Lin Carter.

I’ve discussed Carter’s work before, and I subscribe to the more or less standard view that he was not a very good writer of fiction, but that his contributions to the field as an editor (or “consultant”) were tremendous. And nowhere more so than in this series of books — though Ballantine’s oversight was also important.

The first volume was The Blue Star, by Fletcher Pratt, a reprint of a 1952 novel. The final official Ballantine Adult Fantasy publication was #65, Over the Hills and Far Away, by Lord Dunsany.

[Click the images for Adult Fantasy versions.]

Those two volumes represent a couple of “types” of books that Carter and Ballantine chose to reprint: The Blue Star was a novel that had only appeared somewhat obscurely in a genre publication (in this case, the first Twayne Triplet), while Over the Hills and Far Away is a collection of some of Lord Dunsany’s best fantasy tales, most from the first two decades of the 20th Century.

Ballantine published other novels and collections rescued from the fantasy pulps (or from obscure publishers) — books by Pratt, Clark Ashton Smith, H. P. Lovecraft, L. Sprague de Camp, Hannes Bok, and Poul Anderson, for example; and he also published novels and collections that had first appeared in non-genre sources, in the late 19th or early 20th centuries — writers like Dunsany, H. Rider Haggard, William Morris, William Hope Hodgson, James Branch Cabell, George MacDonald, and E. R. Eddison. They also included some anthologies edited by Carter, of fantastical tales with similar provenance.

|

|

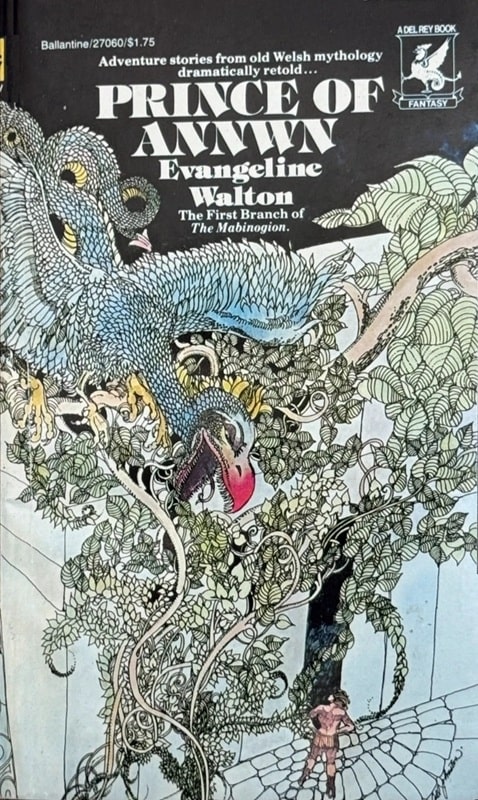

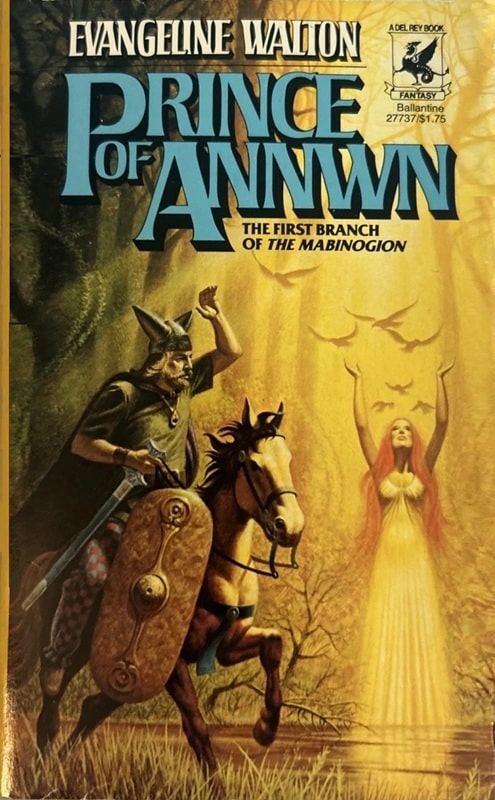

The first novel in Evangeline Walton’s Mabinogion sequence: Prince of Annwn

(Ballantine Books, November 1974). Cover by David McCall Johnston

The series rescued a few writers from near complete obscurity — Hope Mirrlees and C. J. Cutcliff Hyne are two such. There were also a couple of much older books — a prose translation of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso, and a restored version of William Beckford’s Vathek. And one sort of outlier — a great novel, fantastical but hardly in the mode of the rest of the Adult Fantasy series: G. K. Chesterton’s The Man Who Was Thursday.

But how about original novels?

|

|

|

|

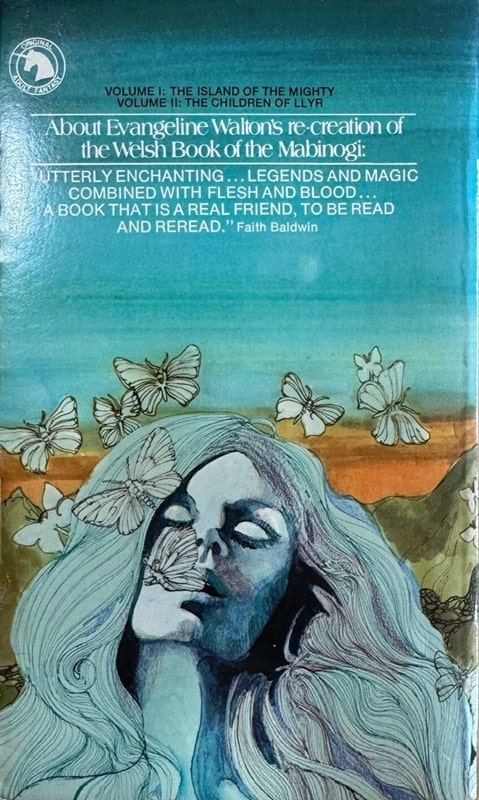

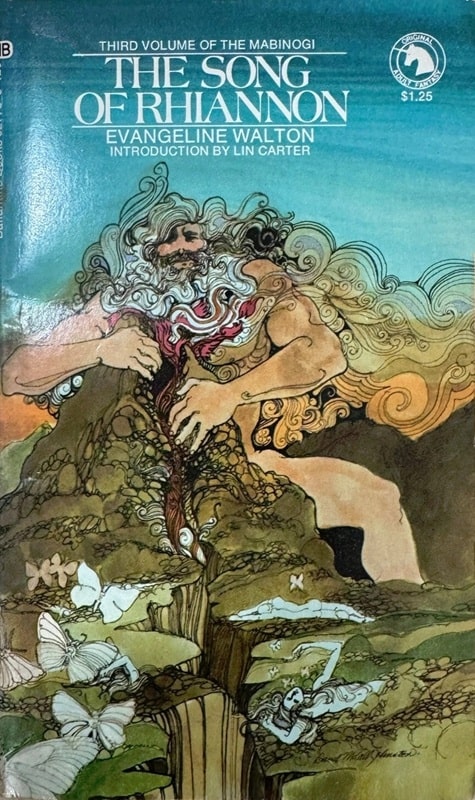

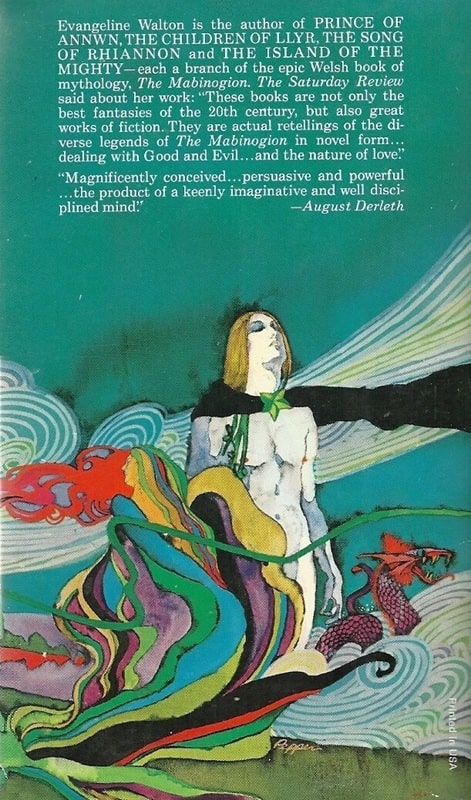

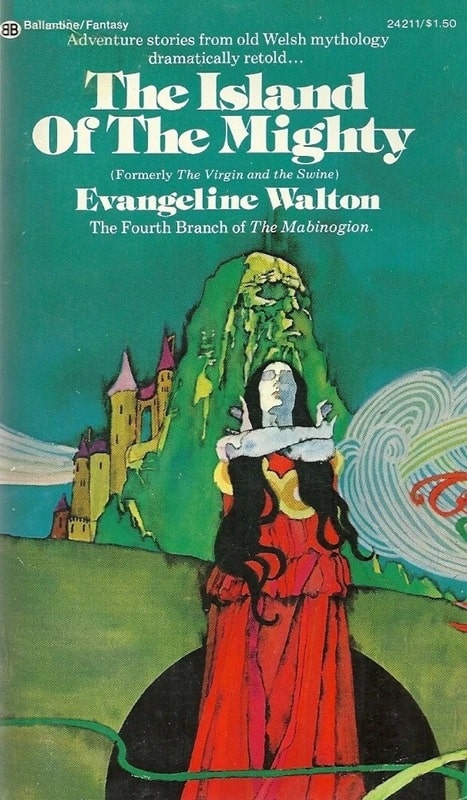

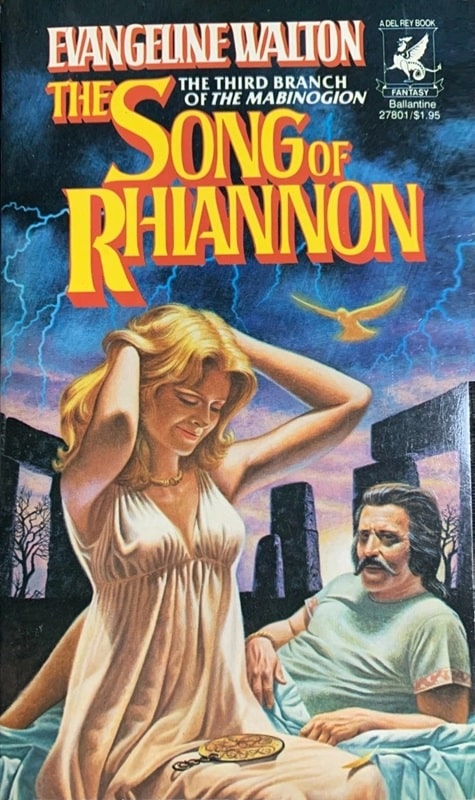

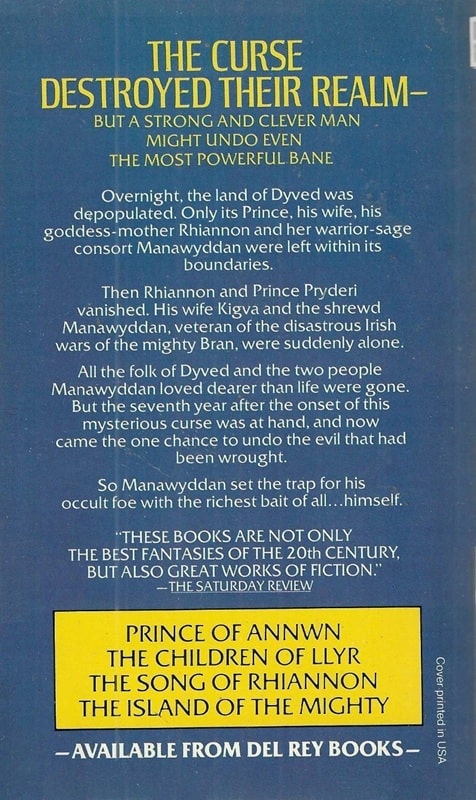

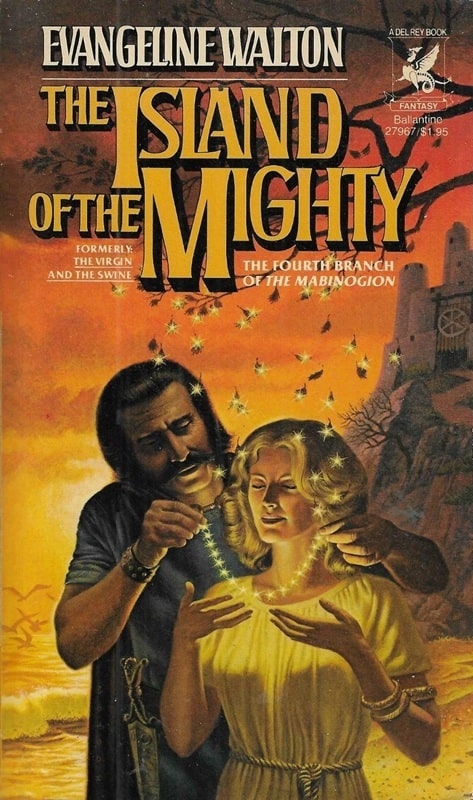

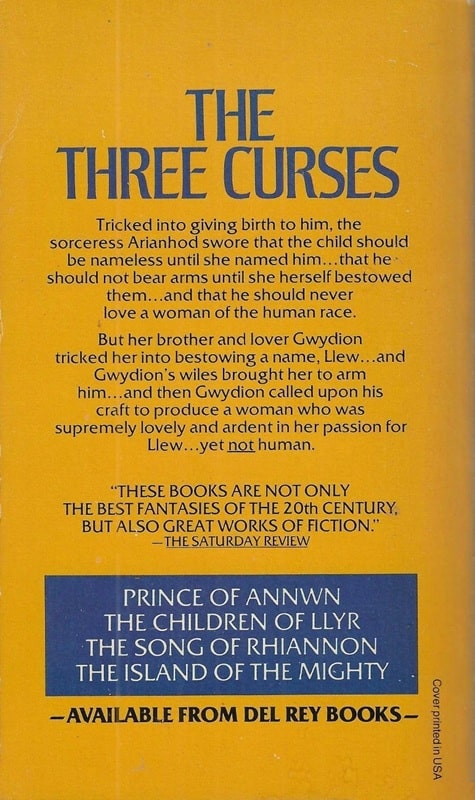

The last two novels in The Mabinogion: The Song of Rhiannon and The Island of the Mighty

(Ballantine Adult Fantasy #51 and #18, August 1972 and July 1970). Covers by David Johnston and Bob Pepper

I confess I had assumed for some time that the Adult Fantasy series was all reprints. But in fact there were some originals: some of the early Deryni novels from Katherine Kurtz, for example, and Hrolf Kraki’s Saga by Poul Anderson, Sanders Anne Laubenthal’s Excalibur, and a posthumous novel by Hannes Bok.

And a few novels by Evangeline Walton. And therein lies something of a story. (Thanks to Douglas Anderson, who has extensively researched Walton’s archives, and who related most of the information below to me.)

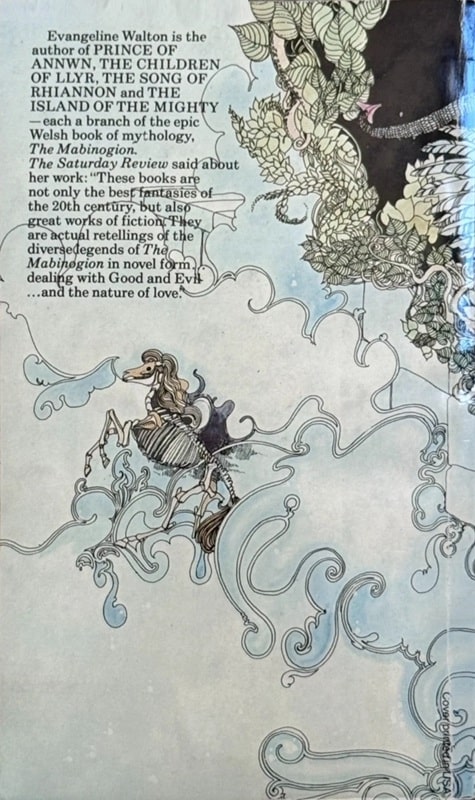

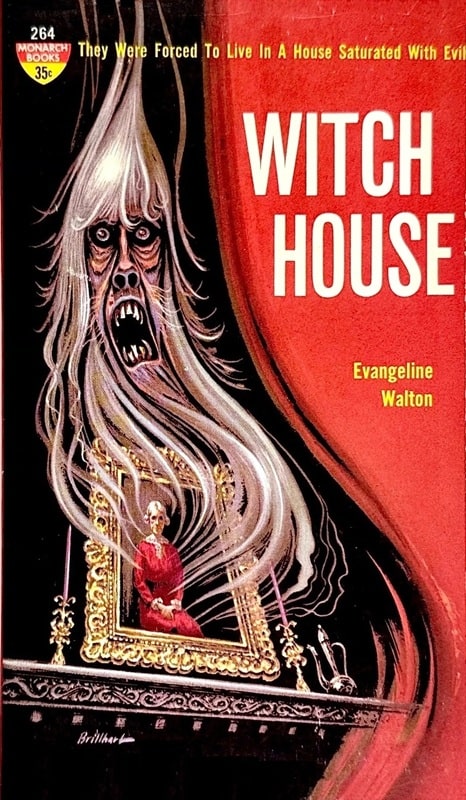

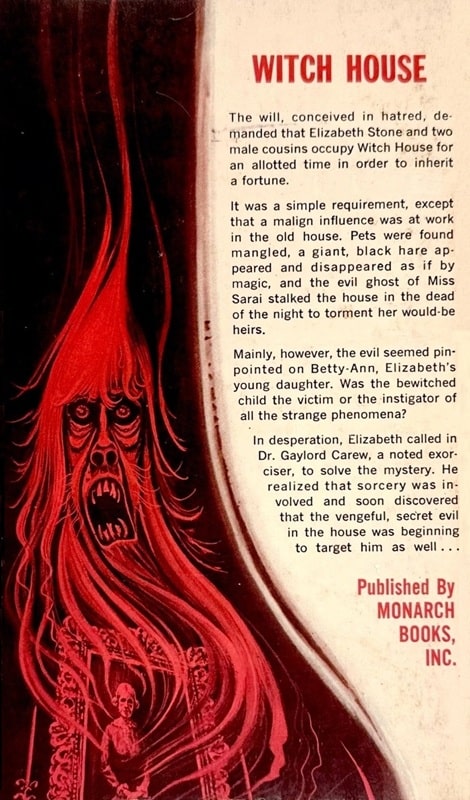

Walton (real name Wilna Evangeline Ensley) had published The Virgin and the Swine, a novel derived from the fourth branch of the Welsh Mabinogion, in 1936. She had planned novels based on the other three branches, and had written one based on the second and third branches, but could not publish them when the first book didn’t sell well. She published a couple more novels in different genres over the next few decades, including multiple editions of her second novel Witch House, first published in 1945. She wrote several further novels that were not published for a number of reasons, including some publisher misconduct (or so Walton definitely thought!) One novel was lost when the publisher’s offices were bombed during the Blitz. Though she kept writing, her difficulties with publishers eventually led Walton to stop submitting her work.

|

|

Witch House by Evangeline Walton (Monarch Books, February 1962). Cover by Ralph Brillhart

In later years Lin Carter read The Virgin and the Swine, and recommended it for the Adult Fantasy series, wherein it was reprinted in 1970 as The Island of the Mighty, Ballantine Adult Fantasy #18. Walton would claim that Ballantine had not contacted her before this reprint, assuming she was dead, much as actually happened when they reprinted Hope Mirrlees’ Lud-in-the-Mist. However, she was playing a bit fast and loose with the facts in search of a better anecdote — Ballantine did obtain her permission before publishing the book.

Walton had completed a novel, The Brothers of Branwen, based on the second and third branches of the Mabinogion. She sent this to Ballantine, who had her split the book in two, due to its length. One half, The Children of Llyr, appeared in 1971, and The Song of Rhiannon came out in 1972. Meanwhile Walton finally wrote her version of the first branch, and Prince of Annwyn appeared in late 1974 (by which time the Adult Fantasy line had officially been discontinued.) The novels were written (and published) out of internal chronological order (and out of the ordering of the branches of the Mabinogion), but were reordered in future printings as follows:

1. Prince of Annwn (1974)

2. The Children of Llyr (1971)

3. The Song of Rhiannon (1972)

4. The Island of the Mighty (1970)

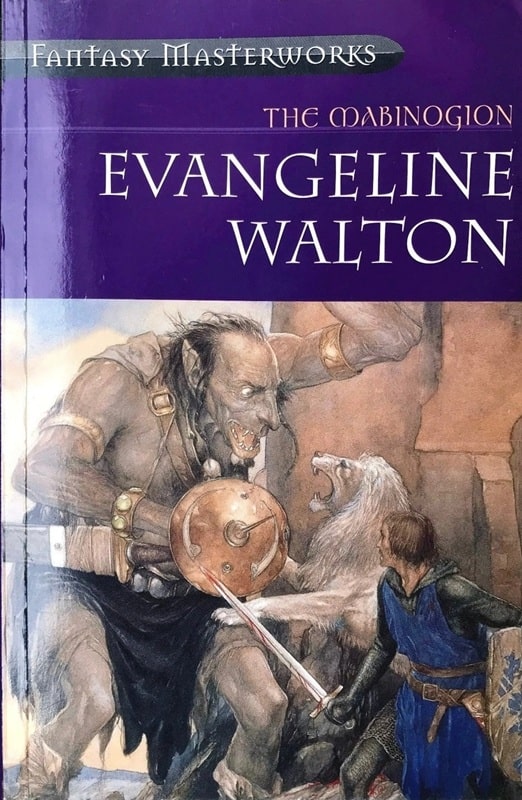

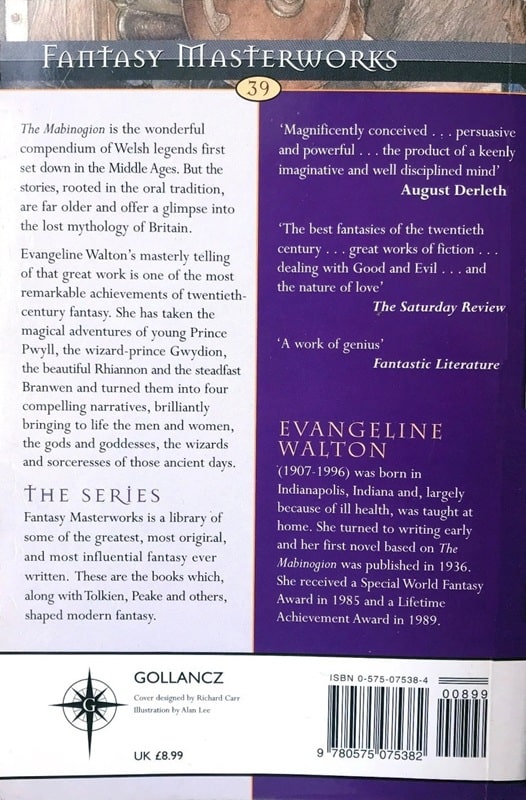

Del Rey reprinted the entire sequence with new covers in 1978/79, and all four volumes were published in an omnibus edition by Del Rey in 1974, and again by The Overlook Press (2002) and finally as Fantasy Masterworks #39 by Gollancz/Orion in 2003 (see below).

|

|

|

|

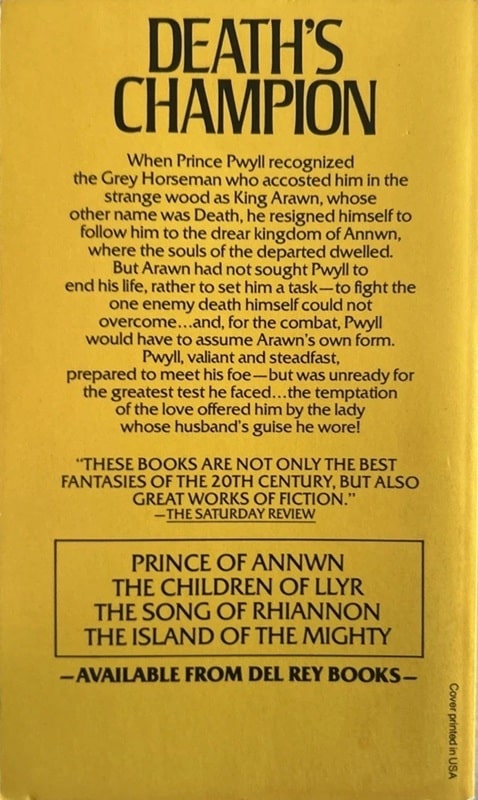

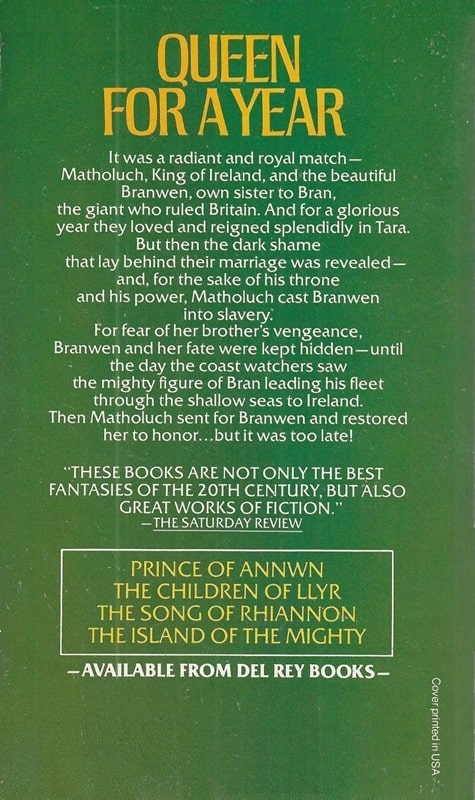

Del Rey editions of Prince of Annwn and The Children of Llyr (Del Rey,

November and December, 1978). Covers: uncredited, and Howard Koslow

Walton’s late novels received a good deal of praise, and The Song of Rhiannon won the Mythopoeic Fantasy Award in 1973, and she was given a Life Achievement World Fantasy Award in 1989. She was not, as far as I can tell, of Welsh ancestry — she was born in Indianapolis in 1907, moved to Tucson, AZ, in 1946, and died in 1996. Apparently Stevie Nicks bought the rights to the Mabinogi novels with the hopes of making a movie from them (though Nicks’ famous song “Rhiannon” is actually based on a completely different novel, Triad (1973), by Mary Bartlet Leader.)

The Children of Llyr announces itself at once as a tragedy. It opens with a sequence in which Llyr, a servant of the King, goes to collect taxes. One of the chiefs he visits is incensed, and by evil means imprisons Llyr and his men, and as a ransom demands to spend a night with Llyr’s lover Penardim, the King’s sister, and mother of Llyr’s son Bran. (Their culture did not have marriage.) Penardim agrees, and the man impregnates her with twins — and of course is (legally) killed by Llyr soon after. Penardim’s twins are Nissyen and Evnissyen. A few years later Llyr and Penardim have a daughter, Branwen.

The main action occurs after the four children or Llyr are adults, and Bran is King (as in their culture nephews inherited the titles.) Nissyen and Evnissyen have been raised as true sons of Llyr, but they are light and dark — Nissyen is honest and sweet-tempered, and Evnissyen is jealous and suspicious. When Matholuch, King of Ireland, comes to Bran’s realm, the Island of the Mighty (Great Britain, though the Mabinogion emphasizes Wales), he falls in love with Branwen, and she with him.

|

|

|

|

Del Rey editions of The Song of Rhiannon and The Island of the Mighty

(Del Rey, January and February 1979). Cover: uncredited, and Howard Koslow

In the end her brothers cannot refuse him, especially as Branwen is willing, and the marriage is agreed to. But Evnissyen, ever searching for ways to cause trouble, kills some of Matholuch’s prized horses, nearly scuttling the marriage plans — but Bran agrees to a steep price in compensation, including a terrible cauldron that raises the dead to be warriors. (This is the same Black Cauldron of Lloyd Alexander’s novel and the Disney film.)

Matholuch and Branwen return to Ireland, and are happy for a while, and have a son. But Matholuch’s advisers are suspicious of the people of Great Britain, and they turn his weak heart against Branwen. And this sets in motion a terrible sequence of events, that in the end leads to utter ruin for the children of Llyr and for Matholuch as well. The events are terrifying, absurdly violent, and deeply sad. (And it does present Evnissyen as someone of whom those in a violent society might say “He needed killin’” — though he gets his punishment as well, and a sort of redemption.)

|

|

Fantasy Masterworks #39: The Mabinogion, containing all four

volumes (Gollancz/Orion, October 2003). Cover by Evangeline Walton

There are fascinating fantastical elements to all this, and it’s all told in clean and powerful prose. In a sense this is an explanation of a coming cultural change, as well. (A result of division between the Old Tribes and the New Tribes of the Island of the Mighty.) Almost no one comes out alive — the innocent nor the guilty, the good nor the evil.

It’s a strong novel of its kind, but I confess that I don’t really think I’ll proceed to Walton’s other novels — instead, I think, I’ll reread Lloyd Alexander, one of my childhood favorites! (Edit: Adam Ford and Douglas Anderson have convinced me I should give Walton’s novels another chance, so I will do so. And Anderson has already edited a restored version of Walton’s 1956 novel The Cross and the Sword (which was severely cut by its original publisher) which was published in April 2025 by Nodens Books under Walton’s preferred title Dark Runs the Road.)

Rich Horton’s last article for us was a review of Starhiker by Jack Dann. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over 200 articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

I read Prince of Annwn many years ago, mostly because of Carter’s rapturous advocacy…and found it very hard going. The fault may be mine, though, and I’ve always intended to read at least the second volume.

I’ve never seen those 1979 Del Rey editions. Those covers are certainly … something.

I think technically the fourth book, Prince of Annwn, postdated the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series proper — it never had the unicorn’s head colophon nor a Lin Carter introduction, although I wouldn’t be surprised if it was originally intended to be a BAF title when it was acquired. Merlin’s Ring by H. Warner Munn is another, similar title from 1974 — that one DOES have a Lin Carter introduction (and the introduction still lists him as the editor of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy series), but again there’s no unicorn’s head on the cover

Rich, this is very interesting. I have never heard of Evangeline Walton before. I don’t feel the need to read her now, but I am glad I read about this.

The Sword Is Forged, a novel of Theseus and the Amazons, was Walton’s best published novel in my opinion. It was supposed to be the beginning of a Theseus cycle; I wish she’d been able to finish that.

I understand that she didn’t write any more in that cycle because she thought Mary Renault’s Theseus novels had crowded hers out, or something like that.

Rich – and everyone – you gotta read the other three novels. They are some of the most amazing books I have ever read. Completely their own thing. She had come a long way in the forty years between books and the other three books are superb.

Thank you for writing about Evangelyn Walton. She is quite lost to the discourse and I think that is a terrible shame.

I’ll give them a try. Which would be the best to start with, do you think? (Though I’ll have to look for the older editions, not those late ’70s Del Rey reprints with the terrible Kreslov covers (the guy on the Song of Rhiannon cover is sporting a ’70s pornstache, if you ask me!) )

hi rich – just saw your reply, sorry. i read them in the ballantyne editions and went by the reading order they give, which is 1) Prince of Annwn, 2) The Children of Llyr, 3) The Song of Rhiannon and 4) The Island of the Mighty. they are just so much their own thing completely unbeholden to any conceit of fantasy formula, things of independent logic and no presumption. I have a real desire to see these books gain a wider audience.

Hi – how may one contact the owner of this website to submit an idea for publication? Thanks.